Interview with Yasmina Barbet

https://www.yasmina-barbet.com/

Yasmina Barbet, is a French photographer trained at the IED in Rome, developed in Paris a visual approach enriched by drawing, art history, and image processing. Upon returning to Rome, she created a personal online photographic archive in 2008.

Since 2009, she has begun a collaboration with Wostok Press, covering major events such as the Vatican and the festivals of Venice and Rome. She has published several works, including Sénégal Natangué, presented at the Italian Senate.

Winner of the 2nd "Lorenzo il Magnifico" prize at the 2025 Florence Biennale, and 3rd in 2017, her work has been featured in solo and group exhibitions across Europe and the United States.

She engages in imaginal research that explores the emotional nuances of the psyche and the inner states we experience, sometimes drawing on mythology—a profound and timeless mirror of the human soul.

She merges her own photography with digital techniques, creating an introspective and contemporary visual universe.

Your work often explores the boundary between documentary clarity and a dreamlike symbolism that seems to emerge from the subconscious. How do you understand this oscillation between bearing witness to the world as it is and transforming it into visual allegory? And how does this dual approach allow you to build a contemporary visual language capable of embracing both truth and imagination?

Hello, It is true that reportage and symbolic artistic imagery are two aspects that, at first glance, seem completely opposed. Reportage places us at the service of reality: we compose from it, we try to capture its essence, and we render it as faithfully as possible. The artistic approach, however, works differently: it fragments reality in order to recompose a more intimate, more interior image.

For a long time, I hesitated to bring together on the same platform my years of reportage and my more symbolic creations. They testify to different journeys, distinct periods of my life. Reportage was an extraordinary experience: it opened me to the world, taught me to seize the moment, and certainly my more constructed images still carry its influence. A language between truth and imagination… Perhaps the membrane between truth and imagination is very thin. Photographing reality also means photographing it through our own filters: is it then completely true? And when we deconstruct reality to invent an inner image, is that not also true?

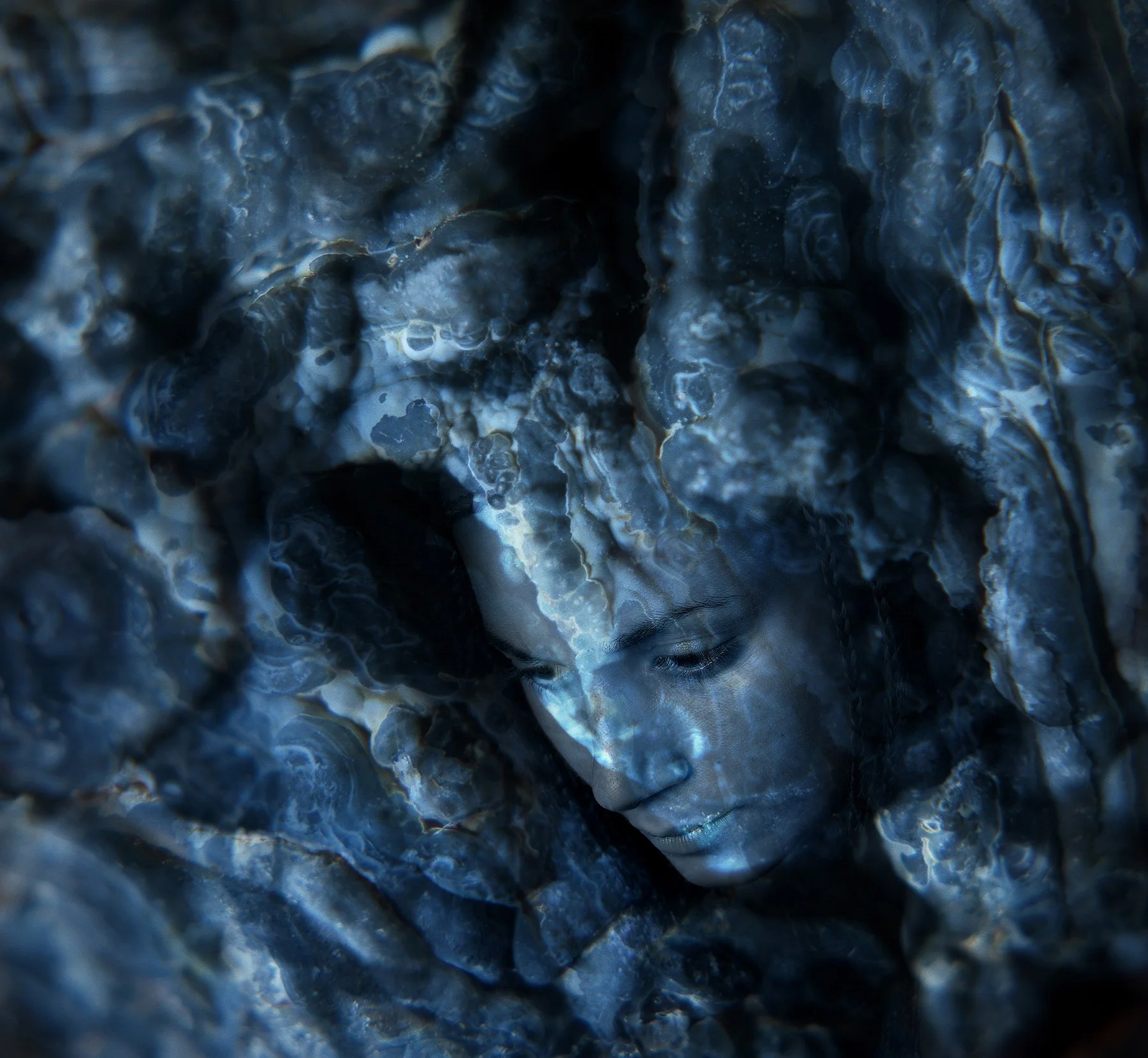

Throughout your career, you have cultivated an intense attention to the expressive capacity of the human face, fragmenting it, layering it, or recomposing it in ways that often destabilize fixed identities. How do you conceive of portraiture today, in the age of digital overabundance, and what ethical or aesthetic questions guide your decision to distort, veil, or reveal certain aspects of the human subject?

Thank you for highlighting this aspect. Indeed, I love portraiture: it reveals far more than the features of a face; it reflects personality, emotions, and sometimes even the trials a person has endured. A simple portrait already says much about someone’s inner life and personality. When I recompose a portrait, I try to add an emotional touch by layering it over a background where color, texture, and atmosphere become resonances. This background acts as an amplifier, exalting the inner state that the image reveals, while aesthetics remain secondary, in the background.

Your biography describes years of movement between France, Italy, and other European cultural epicenters, each with its own layers of art history, mythology, and sociopolitical realities. How has this geographic and cultural nomadism shaped the evolution of your visual syntax, and which elements of these territories continue to resonate in the symbolic architectures of your works?

Living between France and Italy is an invaluable privilege: two lands of exceptional cultural and artistic richness. Their influence on my journey is undeniable. From childhood, I felt a deep attraction to art, first as an observer. This is no doubt what later led me to photography. I was fascinated by the great French masters such as Henri Cartier-Bresson and Doisneau, by the Italian Gianni Berengo Gardin, and of course by the immense Salgado. Yet beyond photography, my desire was to explore a broader vision of the image. Even at a young age, I sought to use photography as a language, a means of artistic and personal expression. To this day, France and Italy continue to amaze and move me through the power of their heritage, the genius of their artists, and their vibrant creativity...

I also discover other countries, for traveling means allowing oneself to be imbued with the soul of places. Each land reveals a story, an energy, an imprint embodied in painting, sculpture, or architecture. These works defy time, transmit messages, and invite us to listen to the memory of the world — they inevitably influence us.

Many of your images seem to be founded on the tension between the visible and the invisible, between the instant captured by the camera and the elusive inner world. How do you manage this tension between technical precision and emotional or psychological depth that resists representation? What strategies allow you to make these intangible states perceptible to the viewer?

I love these words: the tension between the visible and the invisible that is exactly it. Henri Cartier-Bresson said, “To photograph is to align the head, the eye, and the heart on the same line of sight,” which I find very true. I would also add the soul, memory, intuition, intention, presence… This tension resembles the string of a bow drawn tight, ready to release its expression. In reportage, the invisible is that inner filter that shapes our perception of reality. In art, during the creative search, there is a similar tension: making visible all the emotion, perception, and feelings that inhabit us.

Critics writing about your work often refer to emotional layering, optical stratification, and symbolic resonance. When you create these composite images, are you conscious of designing them as psychological maps rather than conventional photographs? How do you orchestrate light, texture, and rhythm to lead the viewer into the states of mind you wish to evoke?

I really like the term “psychological map” that you used, because it fully resonates with the original impulse of my project: an exploration of the psyche, a dive into our inner and emotional states. To give form to this approach, I rely on my “backgrounds,” which are a base of images I created in medium-format macrophotography.

They constitute a kind of visual archive from which I later draw. These backgrounds, through their chromaticity, material, form, and atmospheres, represent for me an emotional substance. Onto these backgrounds, I then superimpose my subjects: they inscribe themselves in the space, inhabit it, and amplify the emotion I seek to reveal. Thus, the work is built as a symbolic and affective stratification. The viewer is invited to prolong this experience: they complete the work with their own intimate filters, their sensitivity, their receptivity, giving each encounter a personal resonance.

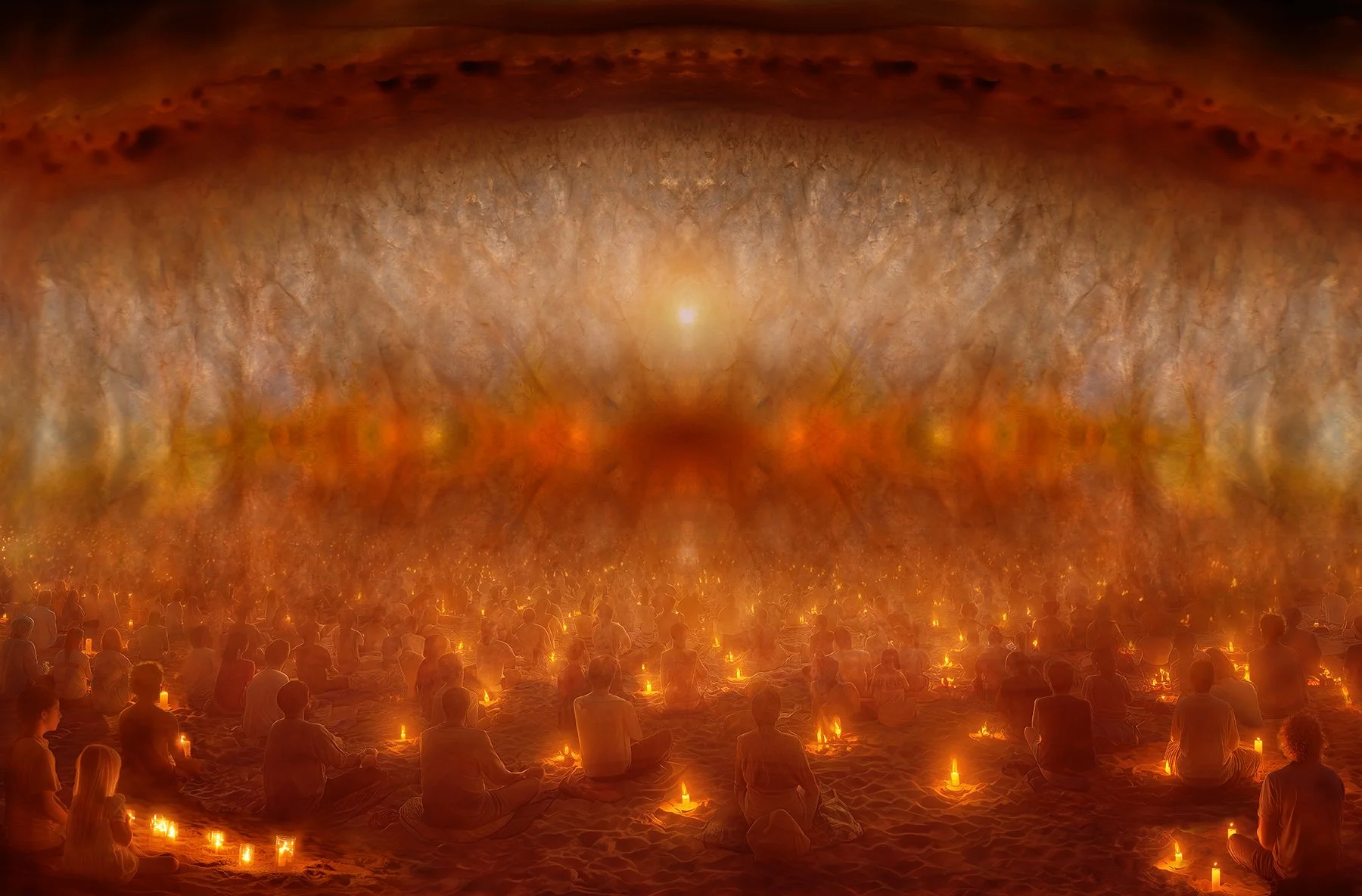

Your artistic practice is characterized by a constant dialogue with mythology, memory, and archetypes, suggesting that the contemporary psyche still relies on ancient symbolic structures to understand itself. What draws you to mythological thought as a tool for interpreting current emotional realities? How do you merge mythical imagination with the immediate visual language of contemporary digital culture?

I have long been interested in Jungian psychology, which revealed the power of archetypes as deep structures of the psyche. Only recently have I turned toward mythology: it acts as a timeless matrix, a symbolic fabric that connects us to foundational narratives. These stories, despite the centuries, continue to shape our imagination and illuminate our emotions; they are mirrors of the soul. They belong to a collective memory. What interests me above all is what goes beyond narration: the raw emotion, the state of being of the characters that belongs to our deepest human nature. Contemporary tools, especially those related to digital imagery, open new pathways and a fresh exploration of visual expression.

In several of your works, you seem to invite the viewer to immerse themselves in the very process of perception, allowing the image to unfold not as a static object but as a temporal sequence of revelations. Could you tell us about your relationship to duration and how the temporal dimension of photography and digital layering becomes an instrument to enrich not only the image but also the viewer’s experience?

I am touched by your perception. In certain images, such as Fear or Icarus, one can recognize the influence of the present moment inherent in reportage: it is somewhat like a snapshot of an emotional state. In Icarus, for example, it is the very moment when ecstasy ignites. Conversely, other works open onto a different temporality: they do not freeze a single instant but unfold as timeless questions, open to whoever wishes to grasp or respond to them… In both cases, as you say, digital layering becomes an instrument to enrich emotional expression, to reveal it.

You affirm that images are inseparable from inner journey, consciousness, and intuition. As your work evolves in rhythm with your own transformations, how do you reconcile personal introspection with universal resonance? How do you ensure that the intimate narratives contained in your images remain accessible to a diverse audience?

Yes, I believe that images are inseparable from the inner journey; I could not do otherwise. I do not know what audience they encounter. They are intimate narratives, silent letters that I release into the flow of the world, a bit like those bottles once entrusted to the drift of the oceans, offered to the unknown tides, carrying the naïve hope that someone might one day read them!

You have developed a singular approach to digital manipulation which, far from concealing its artifice, embraces it as a form of visual truth. In your view, what does digital technology bring to photographic art today that previous generations could not apprehend? How do you preserve authenticity and emotional intensity within a medium often associated with fabrication?

I believe that in the course of art, each technological evolution has always marked a rupture followed by a new beginning. When photography appeared, the world of traditional painting felt threatened and partly collapsed. Yet this rupture opened the way to new movements of thought: Impressionism, then abstraction in painting… Photography became an unprecedented language, a means of expression in its own right. I think of Man Ray, who made it an art. Then came Photoshop and the digital era. Again, traditionalists in photography felt threatened. But gradually, it was understood as an interesting tool, opening new possibilities of expression.

It is, however, a medium with its limits, since it requires a quality base image and a founding idea. Today, artificial intelligence in turn disrupts everything, since it is enough to be a bit of a poet and to formulate beautiful phrases for the machine to create magnificent images, without any technical training. I admit this is unsettling…

When I began 25 years ago, I created my backgrounds in medium-format film, my subjects in the studio, and I used the first versions of Photoshop, where many elaborations were still manual. I am glad to have known analog photography. One cannot stop progress, but one can observe what it brings us. Throughout time, artists have used artifice to convey what they wished to express. I believe artifice must challenge the artificial: it must remain a tool, a means at the service of the artist and of the true message they wish to transmit.

For you, spirituality is not simply a theme but an underlying current that permeates the emotional and symbolic architectures of your images. How does spirituality influence your creative process, your perception of the world, and your understanding of the human psyche? In what way does your art become a space where spiritual intuition and visual form can meet and give birth to meaning?

I greatly appreciate this phrase by Jean Cocteau: “Prayer and love share the same secrets.” At times, I deposit some of these secrets into art, like silent confidences offered to the free interpretation of the viewer. Thus, the work becomes an intimate space where the spectator may, in turn, guess, welcome, or prolong these mysteries.

Yasmina Barbet

Too Much Light of Icarus (mythology)

the seal of the young shaman

The Kiss

Spiritual Awakening

Sadness

Rise into Light

Meeting in a space-time hut

Divine creation

Daedalus' shadow is Icarus' too much light (mythology)

Between one eternity and another

Between one eternity and another 2