Interview with Karel Vereycken

Born in 1957 in Antwerp, Belgium, Karel VEREYCKEN graduated from the Institut Saint-Luc in Brussels and trained in engraving at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts, where he obtained a certificate of passage « with distinction. ».

Today, in France, he concentrates on writing about art history, producing audio guides and of course watercolors and engravings.

In France, as a member of the Fédération nationale de l’estampe, he confirmed his technical mastery at Atelier63 and continued to perfect his skills in the Montreuil workshop of Danish engraver Bo Halbirk.

RECENT HONORS IN 2025

“NOVEMBER 25 ARTIST OF THE MONTH” of the Camelback Gallery, Scottsdale, Arizona, USA;

“FINALIST CERTIFICATE” for the Paris Exhibition of the Circle Foundation of the Arts, New York, USA;

TALENT PRIZE AWARD for the “13th Open” International Juried Art Competition of

Teravarna, San Francisco, USA;MODERN RENAISSANCE MAGAZINE, London, UK, two page article with 5 etchings and watercolors;

HONORABLE MENTION for the « 10th FIGURATIVE » contest of Teravarna, Los Angeles, USA ;

“100 ARTISTS OF EUROPE” selected to be included in the 2026 edition of this book by Culturale Lab, Lyon, France ;

TOP IN CATEGORY AWARD for Printmaking by the Circle Foundation for the Arts (CFA), Los Angeles, USA;

TALENT PRIZE AWARD for the “8th Animal” International Juried Art Competition of Teravarna, Los Angeles, USA;

HONORABLE MENTION AWARD for the “8th Water” International Juried Art Competition of Teravarna, Los Angeles, USA;

COLLECTORS ART PRIZE | ART LEGENDS OF OUR TIME, a prize awarded by the Contemporary Art Curator Magazine every two years.

UPCOMING EXHIBIT

December 2025: Galerie Mona Lisa, 32, rue de Varenne, Paris 75007.

Karel, your trajectory moves between engraving ateliers, historical archives, and the pedagogical space of guided museum tours. How do you negotiate the tension between craft as a rigorously transmitted discipline rooted in the teachings of Herman Cornelis, the anatomical exactitude of Saint Luc, and the engraving lineage of the Academie Royale, and your commitment to metaphor as an emancipatory strategy that invites viewers to discover meaning rather than receive it passively?

In all modesty, I would compare my trajectory to that of the Renaissance poet and thinker Dante Alighieri in his Commedia. The Flemish sculptor Herman Cornelis guided me, a young boy, through the “Inferno” of mere seeing with the eyes of copying rather than the eyes of analysis. Saint Luc and the Académie Royale were, at best, the “Purgatory,” enabling me, an adolescent, to perceive the substances and movements behind the forms, much like one learns to see the muscles and their dynamics behind the human shape.

“Paradise” only came within reach when, influenced by the American polymath Lyndon LaRouche, I, as a young adult, studied Plato (as opposed to the “neo-Platonists”) and some of the Flemish “mystics,” such as Ruysbroec and the Baghdad genius Al-Kindi, who moved from the immediate causes to the final causes, the Prime Mover.

As a result, I embarked on the path of watching with what the Renaissance 15th-century theo-philosopher Cusanus calls the “Eyes of the Flesh,” moving toward seeing with the “Eyes of the Mind,” getting a glimpse and a sense of the invisible intent behind the existence of man, nature, the cosmos, and the wonders of its operations.

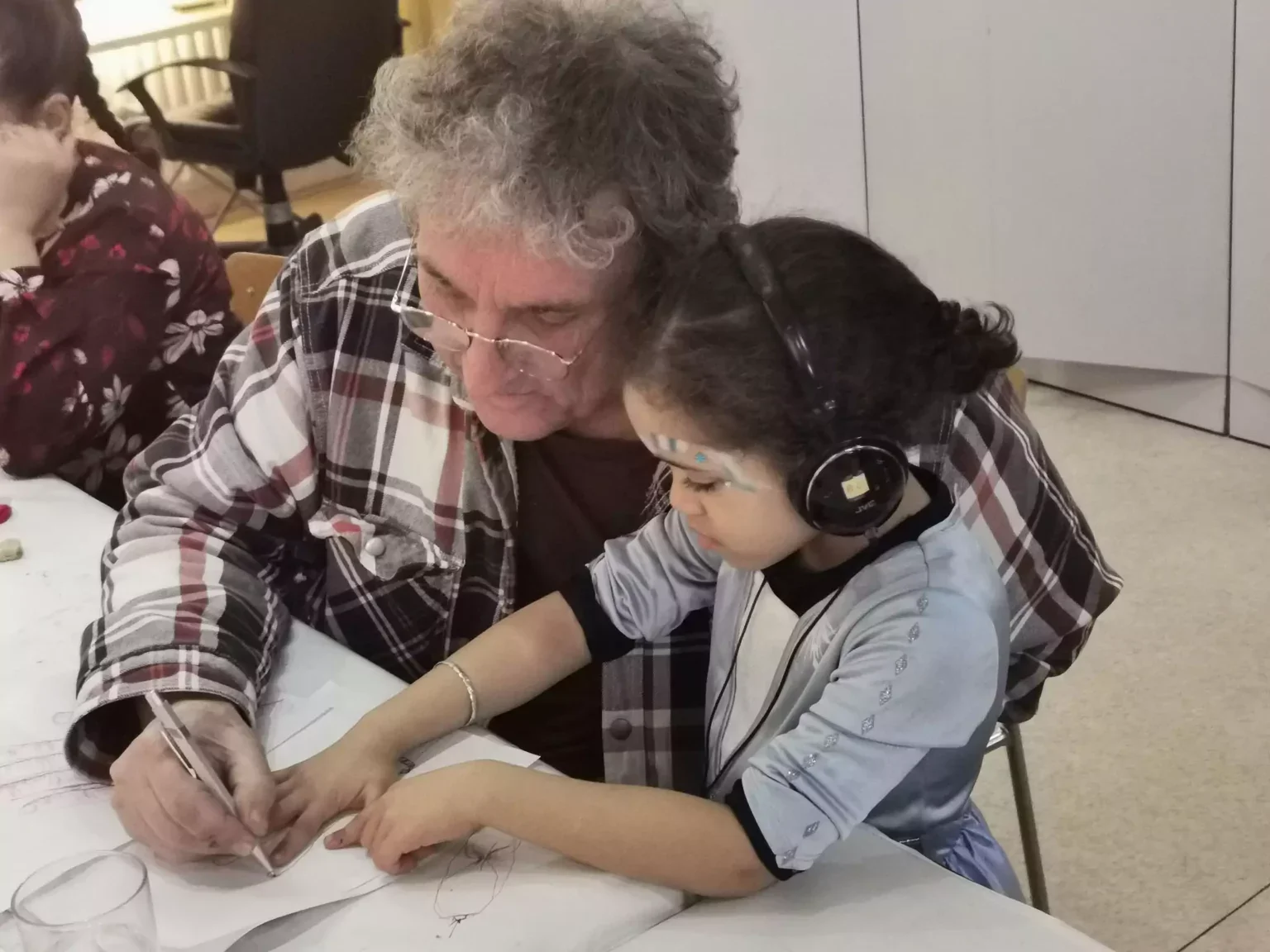

But for me, having inherited a strong sense of social usefulness from my mother, art had to be something concrete something I could develop as a gift for others. At one point, I saw my career as a revolutionary pedagogy, helping autistic children grow by expressing themselves.

I wanted to be like Virgil, but using painting to guide Dante out of Hell, or like Charon offering artworks to lost souls crossing the Styx. From the higher standpoint that of Cusanus’ “coincidence of the opposites” formal tensions vanish, especially if one models oneself on the wisest Bodhisattvas of Mahayana Buddhism, for whom the aim of existence is not attaining the state of perfection (Nirvana) for oneself, but helping others move in that direction.

Growing up in a working-class family shaped by the aftermath of war, you were exposed early to Flemish masters, the cartographic imagination of Plantin’s Antwerp print shop, and the artisanal world of ship repair. To what extent do these three genealogies of manual labor, print culture, and Early Netherlandish vision form the silent “infrastructure” of your imagery, particularly in the way you construct spatial transitions between the visible and the metaphorically intelligible?

The science of map-making shares common ground with great art. A mapmaker doesn’t simply copy what his eyes can see; rather, through various means, he creates an image that relates with great precision to reality even if, for him, it is only physical reality. In that sense, just like a good artist, he "paints the invisible." Using these maps, or building physical objects from designs, allows us to discover the cracks in our theories and preconceived plans. In terms of constructing spatial transitions between the visible and the metaphorically intelligible, the geometric paradoxes exploited by Piero della Francesca a painter protected by Traversari and Cusanus— are mind-blowing. The great French art historian Daniel Arasse speculates how Leonardo da Vinci’s genius might have been influenced by Cusanus’ treatises, especially the latter’s 1453 book The Vision of God.

Abbey of Vallemagne, watercolor, 55 x 70 cm, 2024

artist at the Abbey of Vallemagne, 2025

H2O, zinc plate that became a sculpture, 2025. The philosopher discovers the water of the fountain of the Abbey and its poetic relation with that burning in the stars.

H2O, intaglio etching on zinc, 2025.

Your distinction between “symbol” and “metaphor,” the first a coded convention, the second a cognitive spark born of paradox, suggests an epistemology of art that resists both semiotic reduction and contemporary cynicism toward meaning. Could you elaborate on how, in your own practice, metaphor becomes not only a pictorial device but an ethical stance against what you describe as the attack contemporary art has made on poetic meaning?

In my later life, becoming a friend of Michael Francis Gibson (1929-2017), the International Herald Tribune's art critic, an erudite musician, and an expert on Bruegel, was decisive. His book Symbolism clarified the lines of the debate. By thoroughly examining several founding figures of “Modern Art,” Gibson identified with great precision how Symbolism—an aesthetic trend of the late 19th century shifted from “figurative” to “abstract” symbolism. "Modern Art," he rightly claimed, should be “read” as “abstract” symbolism. The form had changed, but not the intent. The early works of Kandinsky, Klee, Picasso, Kupka, Mondrian, and others clearly demonstrate that, in their early paintings, they were "figurative" symbolists. Both Mondrian and Kandinsky, after encountering the mystic ideas of Madame Helena Blavatsky, the founder of the Theosophical Society, shifted from "figurative" to "abstract" symbolism. For Kandinsky, as he describes in several writings, “red” has a symbolic significance, just as “yellow” does, and the same is true for a “triangle” or a “square,” etc. While symbols may have the appearance of poetry, they are, in fact, anti-poetical, since real poetry frees man. The "hidden truths" behind symbols remain the privilege of the happy few.

Metaphorical paradoxes, on the other hand, reach out to each and to all through the very content they carry. My values were already rooted in the quest for the emancipation of the many from slavery, ignorance, and poverty, but also from the secret codes kept by the elites. Therefore, “lyrical abstraction” became unacceptable to my ethical self. And when “contemporary” art became the forced expurgation of any sense of meaning in fact, an ontological impossibility and descended into gratuitous provocation, my stomach turned upside down.

Your creative method brings together Song dynasty landscapes, Gandharan sculpture, Flemish devotional painting, and the bronze heads of Ife. These traditions do not share geography, chronology, or cosmology, yet you treat them as co-participants in a unified humanism. How do you navigate the risk of collapsing cultural distance while still mobilizing these references to construct what you call a “window” onto a deeper, trans historical dimension of compassion and creative love?

To me, real art exists in a "cosmic" dimension above time and location. The object might be "ancient" or "modern," "Eastern" or "Western," in terms of its physical creation, but the art within it transcends those categories. Only contributions to universal art shine forever, everywhere. Charles de Gaulle's best friend was the erudite art historian André Malraux. In his 1947 book Le Musée imaginaire, he wrote that the birth of photography would completely change mankind’s relationship with art, enabling a fruitful dialogue between the most beautiful creations of art through a visual "data bank."

From left to right: Man with the golden Helmet, Gandhara head, Mona Lisa (all in the public domain)

Karel wants his paintings to contribute to the “immortal” dialogue among artworks of all times and cultures, as described in André Malraux’s Le Musée imaginaire.

Your etching Stairway to Heaven stages a meeting between Patinir’s metaphysical terrain and the Huangshan mountains of China, inserting a pilgrim whose path is defined by moral ascent and descent. What does this hybrid landscape reveal about the way you conceive “journeys” in art journeys not only through space but through systems of thought, religious philosophies, and the viewer’s own confrontation with free will?

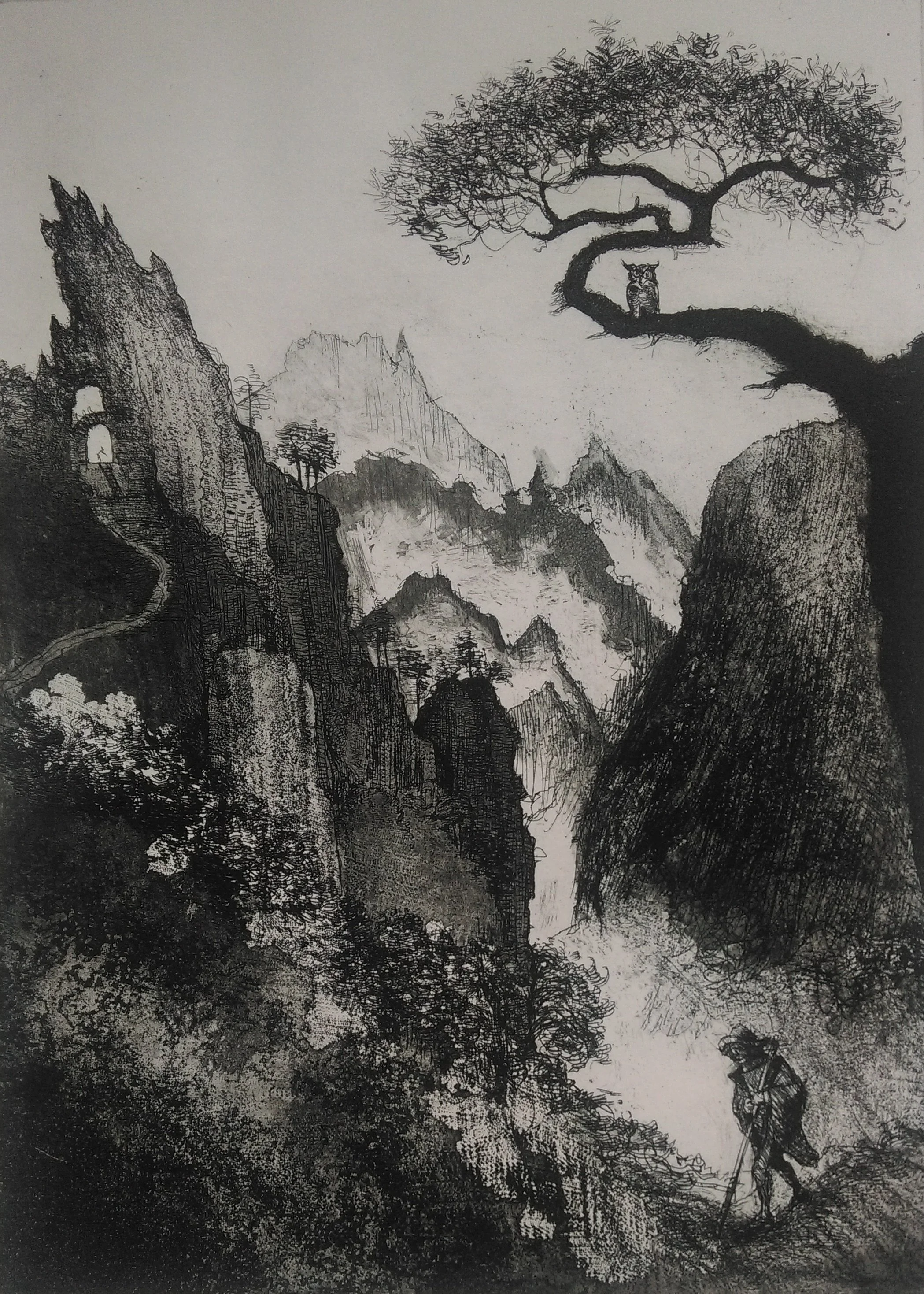

Stairway to Heaven, intaglio etching on zinc, 50 x 70 cm, 2018.

Contrary to photography, painting does not capture the moment as such; it is an act of meditation. Painting, as an object of “spiritual” contemplation, is something many have yet to fully discover. By marrying Patinir with China in my intaglio etching Stairway to Heaven, I aimed to demonstrate this unspoken higher harmony not of form, but of spirit.

Of course, the pilgrimthe homo viator is key. The best part of the history of the Low Countries, where I come from, and as demonstrated by the pre-Renaissance movement of the Sisters and Brothers of the Common Life, is that faith is not merely submission to an "exterior" God, represented by formal churches and their priesthoods, but the personal fine-tuning, at every instant of the journey of your life, of your reason, soul, and sentiment to the intent of the divine or the cosmos.

The Chinese Song Dynasty landscapes, often created by Taoist painters who were discontent with the Confucian bureaucratic rulers while still sharing the overall aim to promote the common good pioneered the concept of multiple horizon landscapes. These works even inspired geniuses such as Leonardo da Vinci in his Mona Lisa.

In 2029, the anniversary year of Da Vinci’s death, I had the pleasure and honor of giving an interview to People’s Daily of China on the influence of Chinese landscapes on the European Renaissance, and Da Vinci in particular. My interview was reviewed and validated by top Chinese experts and published in Chinese on over 50 websites.

The history you recount in which certain strands of abstraction were advanced during the Cold War as a cultural strategy stands in contrast to your commitment to images that stimulate cognitive participation. As a painter, engraver, and historian, how do you understand the political dimension of making meaning legible again, especially in an era when both market forces and institutional discourse often reward opacity?

Karel teaching perspective to a young girl

Towards the end of my training at Saint Luc in 1976, we were informed: “Belgium has the right to produce six artists per year, and you are one of them.” International foundations, which I will not name here, offered to sponsor emerging artists like my classmates and me.

In exchange for funding and name recognition, they requested that our works be painted exclusively in one particular “style” defining the market value of art at the time: “lyrical abstraction” (Kandinsky style). As has been thoroughly documented in Frances Stonor Saunders' 1999 book Who Paid the Piper?...

In The CIA and the Cultural Cold War, Frances Stonor Saunders documents how the CIA, in the 1950s, made secret efforts to infiltrate and co-opt artistic movements, using funds that were mostly channeled through the Congress for Cultural Freedom and the Farfield Foundation. For them, "lyrical abstraction" became the ideological translation of "Western values" in art—"free trade" and total "freedom" decoupled from necessity.

As mentioned before, I encountered this operation in person, and it was a big shock. At the time, it didn’t appear to us as a propaganda enterprise, but the idea of giving up our freedom was deeply unsettling. Resisting this scheme began with resisting myself, as I was, at that time, exploring lyrical abstraction with both passion and enthusiasm. I did study Paul Klee in some depth and worked through Kandinsky’s 1911 booklet Über das Geistige in der Kunst.

Today, we live amid a tsunami of confusion and “organized nonsense,” often deliberately deployed to confuse and demoralize people. Meaning matters, because meaning gives each individual mind the power to act. And the oligarchy seeks to deny that power to all of us.

Art also gives new meaning to old truths. Nothing great can be achieved without inner conviction. Hardworking optimists like Erasmus and his followers Rabelais, Cervantes, and Shakespeare who mocked those who illegitimately confiscated all power for themselves, helped bring down the most barbarous and ugly dictatorships. Art and irony are the weapons of the poor.

Your apprenticeship included rigorous anatomical study through Leonardo and Durer. Yet your later turn toward metaphor, paradox, and the “joy of discovery” shifts the emphasis from corporeal precision to cognitive and affective resonance. How do you reconcile these two pedagogies, the anatomical and the metaphoric, within your current watercolors and etchings, which often appear to operate simultaneously on diagnostic and visionary registers?

View on the Thames, London 1902

Intaglio etching on zinc, 40 x 50 cm, 2025.

Technique, knowledge of anatomy, perspective, and color are mere tools at the disposal of the great masters of imagination. These tools must obey their masters. One must master all of them to the point where they no longer require conscious thought, as they become part of our artistic instinct. Great singers don’t focus on individual notes; they offer music to their audience.

Your long engagement with museum pedagogy, guiding friends through the Louvre, Frankfurt’s collections, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, seems to function as an extension of your artistic practice. In your view, what does it mean for an artwork to “transmit ideas,” and how does your role as a historian and storyteller shape the compositional strategies you employ to make such transmissions perceptible without resorting to didacticism?

Karel with a group of friends entering the Louvre

I’m always astonished by my own ability to find new words to make great works of art accessible, even when I’ve shown them a hundred times before. Each audience awakens in me new energies to “paint” in their minds the few things I can say to help them open their eyes. There’s no need for didacticism when great art itself offers its own high lesson. Plato is right: great art cannot be taught; one can only dust off the viewer’s mind and eyes and give them the wings to fly through the window of the painting.

The story of abandoning music because of rigid pedagogical methods, only to discover creative liberation in drawing, introduces a question about initiation, about how an artist learns to “see” rather than simply to replicate. Looking back on the “copy this” instruction from Herman Cornelis and your later rediscovery of Old Master techniques, how do you understand the dialectic between imitation and invention in forming an artist’s inner vision?

I’ve already partly answered this question in my previous response. It was only after twenty years of copying and delving into the minds and techniques of the old masters that I gained enough mental and technical confidence to embark on my own creative journey. Art isn’t a job or a profession; it’s a way of being. Professional artists, if they lock themselves in the confines of profession and technical performance, tend to become mediocre, and their creativity dries up. You have to fill your lungs with life, with the pursuit of love and beauty, and breathe out with your art.

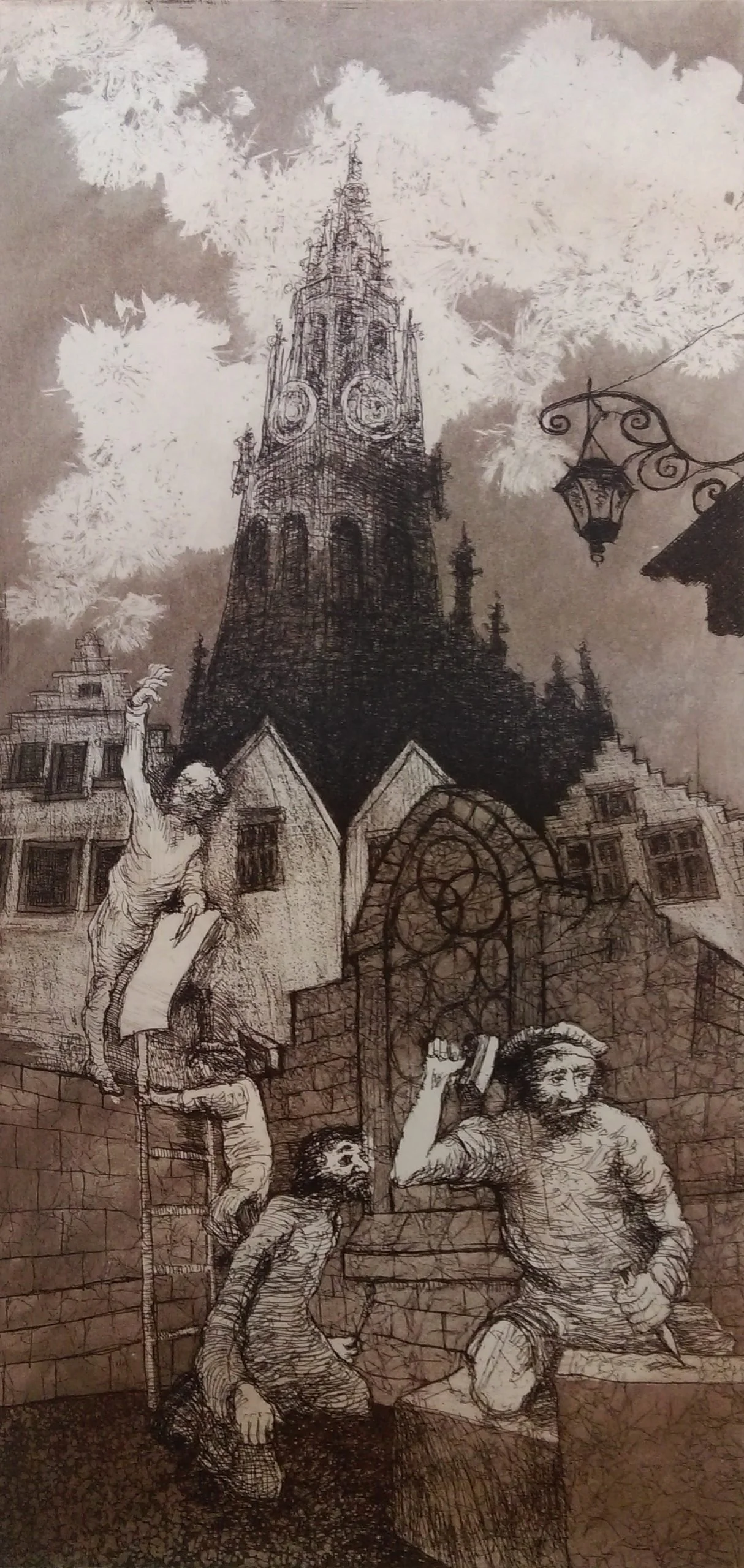

The Cathedral builders of Antwerp, intaglio etching on zinc, 50 x 70 cm, 2020

While the architect takes the proportions from the firmament, the stone cutters try to make it real

You describe your practice as a form of humanistic “intellectual guerrilla warfare,” a striking formulation that links aesthetic experience to resistance against impoverished conceptions of culture. How do you see the role of the contemporary engraver within this struggle, especially at a moment when digital reproduction seems to eclipse the tactile, slow, materially intelligent operations of etching, which you pursue with such historical consciousness?

Producing watercolors or intaglio etchings means taking a step back, a moment of respiration. “Wait a minute” doesn’t mean wasting time, but rather gaining altitude to look at things from above, allowing you to focus on the essentials and move more quickly. Paradoxically, working slowly enables you to delve into more profound realms than the ever-shifting, emotionally driven superficial images on Facebook and social media. A painting is a person. To meet it, you have to take the time to sit close, talk to it, and talk to yourself. There is a growing demand to return to a more human relationship between ourselves as humans and the images produced through deeper thought.