Interview with Veronique Avril

Veronique, your trajectory moves from literature and event scenography to decorative objects and, finally, to an expanded artistic practice that traverses painting, photography, and digital composition. How do you understand this passage not as a sequence of ruptures, but as a continuum of sign-making, where narrative, atmosphere, and staging migrate from language and lived experience into image, surface, and spatial illusion?

For me it’s not a series of breakups. In my professional career, I have been able to sell interior decoration items, and art has come back to me as something obvious. When you find and sell beautiful items, you think to the beauty of the world; you think that they give beauty to people, so by selling beauty, I wanted to create beauty, and naturally, I returned to my first passion.

Art was evident. It was a sign that I had to return to what mattered most. This transition had to happen in my life, this transition had to happen in the continuum of my life, even if I had another job before.

For me it’s not a series of breakups; there were experiences in another world, now it’s an experience in an artistic world.

Much of your work appears to oscillate between figuration and abstraction, refusing a stable stylistic identity. Rather than seeing this as eclecticism, could we read it as a methodological position, an insistence that subjectivity itself is unstable, porous, and contingent? How does this refusal of a single visual grammar function as a critique of fixed identity, particularly within representations of the feminine?

It’s a good question. I don’t like labels. I don’t like the idea that someone can be confined to a single artistic identity. I think that subjectivity is porous and unstable; it’s a vision of art. As an artist, I firmly believe that we must assert ourselves through eclecticism in different styles—painting, drawing, digital, and numeric—to offer people the choice and enable them to develop their subjectivity.

For me, a complete artist is someone who is capable of creating in the broadest sense, someone who is not confined to a particular style and who is able to stand out from one style to another.

I’m not criticizing artists who have an artistic identity; on the contrary, I admire them. I’m just saying it’s not for me.

Your images repeatedly invoke reflection, doubling, immersion, faces mirrored in water, figures dissolving into vapor, timepieces suspended between mechanics and dream. How consciously are you engaging with time as a structural element, not merely as a theme, but as a visual system that governs repetition, delay, and suspension within the pictorial field?

It’s conscious because the time theme is very important for me; time is a part of life. I approached it as a structural element and as a visual element. In my artwork, with repetition, figures and faces in the water, doubling, I choose consciously this visual system, even if the pictorial field is less important.

For people, the audience would have a visual impression, a visual effect that makes an impression—repetition, immersion, timepieces suspended between mechanics and dream. Everything was created to confront this audience with this concept of time, and this notion of time is important to me.

It’s a structural element of some of my artwork.

In works such as United, intimacy and vulnerability operate at a symbolic rather than anecdotal level. The child, the object of comfort, and the surrounding atmosphere seem less illustrative than archetypal. How do you negotiate the ethical tension between aestheticizing suffering and producing an image capable of sustaining empathy without collapsing into sentimentality?

It’s a delicate balance. If you want to show intimacy and vulnerability, it’s hard to have a good balance.

It’s difficult to elicit empathy without resorting to sentimentality, but even if it seems like a cliché, I embrace it, especially in this work I like.

I especially wanted this suffocated atmosphere to highlight the need for love between us.

You know I love this artwork, and for me, I have no ethical tension. The cause of children is particularly close to my heart, so yes, the little girl with the bear is surely archetypal but visually necessary.

I believe that when we want to create a work of art showing feelings, it’s difficult to find a happy medium, as you are criticized for being sentimental or archetypal. In some of my artwork, it’s like that, trying to find a good balance.

Your use of mixed media, acrylics, powders, relief-like textures, and digitally mediated surfaces introduces a pronounced material tension in the work. How do you conceive of materiality in relation to emotion? Is texture for you a carrier of memory, a residue of gesture, or a way to resist the smooth consumption of the image?

Texture is clearly a way to resist a smooth consumption of the image. I need texture and colors in my work to show expression and emotion.

I like to mix all techniques, as I told you. I like the material tension in the work. Texture is a resistance and a way to show a sort of force emanating from my work.

I create for emotion. I create for people who can feel the sense of my work.

You’re right. A pronounced material tension exists in my work, but it’s my way. It’s my resistance.

Photography, in your practice, is approached less as documentation and more as mise en scène, bordering on cinematic construction. How does this performative dimension complicate traditional distinctions between painting and photography, and what does it allow you to articulate about control, fiction, and authorship in contemporary image making?

It’s a fact. My photographs are staged. I adjust every detail, I make elements of my photo, I literally put the objects in the right place for creating a great work that looks like a painting.

You talk to me about cinema, I admire directors, and I stage my photos as a film.

For contemporary art, it allows me to take photographs that I want. It allows me to take photographs that look like paintings rather than traditional photographs. It’s pure creation that I control from A to Z.

It’s more complicated than it appears. It’s not traditional, but it allows me to articulate my contemporary image-making.

The feminine presence in your work often appears introspective, withdrawn, or suspended in interior states rather than positioned for direct address. How do you situate these figures within broader art historical representations of women, and to what extent are you consciously working against the legacies of spectacle, idealization, or objectification?

If the female presence in my artwork seems introverted and withdrawn, it is undoubtedly because a part of me is too. There have been many portraits of reserved women in art history.

I’m not working against the legacy of the show; I’m just working for it.

I’m working to show that you can be a woman, an artist, a creator with introspective and reserved women. I don’t situate myself and my women in art historical representation; I just create painting, digital art, and photographs with women feeling like myself in this world.

You cite Impressionism, Magritte, and Toulouse Lautrec as influences, figures who radically reconfigured perception, illusion, and modern life in their respective moments. How do these references operate within your work today, as formal strategies, ethical positions, or historical echoes that you actively translate into a contemporary psychological context?

If Magritte and Lautrec are part of my inspiration, it is because they knew how to breathe life and ideas into art; they followed their instinct.

Both of them resonate with me, even though I will obviously never be like them.

They are an echo, and like me, they followed their instinct and didn’t want to be like everyone else; they kept their own identity.

I try to convey emotion in my work, to play on an emotional level, to awaken a sense in art lovers.

It’s not strategic; it’s an emotional transmission of my feelings.

Your abstract works, particularly those that evoke liquid, metallic, or cosmic surfaces, seem to abandon narrative while intensifying sensation. Do you see abstraction in your practice as an endpoint, or as another narrative mode, one that speaks through affect, rhythm, and visual density rather than recognizable iconography?

I don’t see anything particularly abstract in my work. I see a mode of expression through colors, texture, and theme. I see a transmission of emotion much more than abstraction.

For me, it’s visual, it’s emotional, but not abstract.

When I choose something that evokes liquid, metallic, or cosmic surfaces, it’s a choice. When I choose a reserved woman or a child with a bear, it’s a choice, but it’s not abstraction.

I want the audience to feel an intense sensation, an intense emotion, something that touches them.

It’s not an endpoint; it’s the beginning. It’s a choice to choose colors, forms.

I want both recognizable iconography and visual density.

You have spoken of a desire for recognizability, not as branding, but as the emergence of a coherent artistic voice. In a cultural landscape increasingly shaped by acceleration, digital circulation, and visual saturation, how do you imagine building a practice that resists immediacy and instead cultivates duration, depth, and sustained contemplation?

I don’t know what I am. I create and I want to be recognized for what I made.

Everyone has their own style, and I have mine.

I hope to resist by cultivating what makes me who I am—my history, my professional career, my depth.

I hope to stay what I am, what I create, what I try to display in sustained contemplation.

I prefer to cultivate depth and my identity rather than give in to the siren call of immediacy, which leads us to throw paint on a canvas and proclaim it genius.

I hope that art lovers will enjoy looking at my works as much as I enjoyed creating them.

That is how creators live on.

fruits on the wall

Cosmo girl

gone girl

Goddess

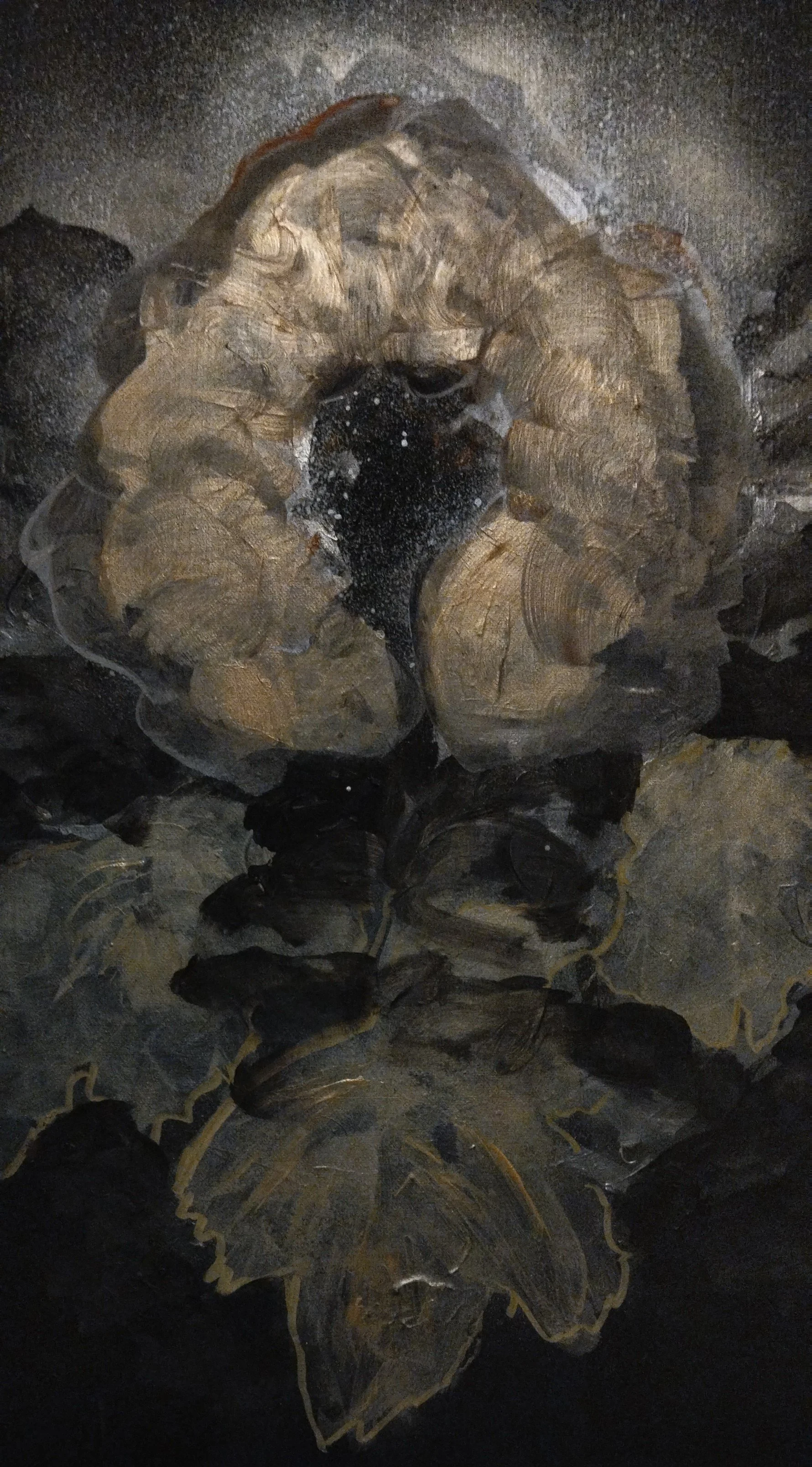

Roses

Bathroom

Glam room

Retro memory

Golden flowers

Into the night

The village

Still life

The island

Passion dechue