Interview with Michel Testard

Photo of the artist in Delhi Gallery Art Indus, 2020, iPhone photo

Michel Testard

wandering painter of faraway worlds

Michel Testard is a contemporary painter whose work is shaped by long-term travel and lived experience across Asia, India, Europe and the polar regions. Born in Japan and raised between continents, he has developed a practice rooted in travel, cultural immersion and sustained encounters with distant places. His paintings explore landscapes, interiors and human figures as emotional spaces rather than documentary subjects, blending observation, memory and imagination.

Figurative and narrative, Testard’s work is driven by colour, atmosphere and feeling. Whether depicting Indian classical musicians, jungles, Goan interiors, Himalayan landscapes or remote Icelandic horizons, he approaches painting as a way of inhabiting places rather than explaining them. Now based in France while continuing to travel extensively, he paints as a participant rather than an observer, honouring faraway worlds through memory, feeling and empathy.

Michel, your paintings are often described as a cartography of emotional geographies, places not simply visited but absorbed into the bloodstream of memory. When you speak of a bend of the Ganges at dawn or the mineral light of Ladakh, it seems you are also describing interior states. Could you speak to how landscape becomes psychological terrain in your work? How does the tension between the external world and the inner remembered world shape your sense of composition, of colour, of the very architecture of the canvas?

The places, people and landscapes I have painted over the years all come from real encounters that touched me deeply. I have never travelled as a tourist; I have always lived inside the places I painted. My years in India — almost twenty of them — shaped me profoundly. I had known how to draw since childhood, but India taught me how to see. Vision there is never neutral; it is ‘darshan’, a way of receiving the world that transforms the one who looks.

This learning came through experience: travelling twice across Ladakh on a motorbike, returning to Kashmir several times, attending classical music concerts before studying the sitar myself, meeting yogi masters in Rishikesh, rafting and diving into the upper Ganges, confronting the vastness of Himalayan mountains and the lushness of Kerala valleys. India was a shock of colour, sound, humanity and light, a world so intense that it shaped my vision and became part of my inner landscape. Yet that inner landscape had older roots. I was born in Japan and spent part of my childhood in Vietnam; my first language was Japanese, though it vanished early. That nomadic beginning created in me a strange mixture of openness and wandering. I have always felt able to adapt everywhere and at the same time belong nowhere. The emotions I experienced in India probably resonated with forgotten impressions from my Far East childhood, as if several continents coexisted within me.

This is probably why landscape in my work is not external. My gaze always carries two faces: admiration, sympathy on one face, and on the other face a quiet melancholy that comes from a lifelong sense of not belonging, almost of loss. This tension shapes the essence of my paintings. I start with an idea but seldom plan a composition. I first draw spontaneous marks and curves; as my hand moves, my unconscious gradually takes over and guides the forms. Then colours and contrasts emerge without calculation, through successive layers, trials and errors. A teacher at the Ateliers de la Ville de Paris once remarked that I belonged to the small number of painters who work intuitively with colour. Over time, I have found that pace and accidents often lead to stronger results than overwork.

I discover only at the end what I have really painted. The external and the internal seem to merge into a certain atmosphere. Some of my canvases carry a trace of melancholy—not by intention, but because they come from a wandering soul travelled and shaped by many worlds. In that sense, I hope my paintings carry a true emotion to the viewer.

You call yourself a wandering painter of faraway worlds, yet one senses in your paintings that these worlds are not distant at all, they inhabit you with a kind of quiet persistence. Do you feel you paint to remember or to keep something alive? How do the act of painting and the act of dwelling in memory overlap for you? Is nostalgia a force, a burden, or a liberation in your practice?

These different worlds stay inside me because I grew up moving between them from an early age. Travel was not something exceptional in my childhood; it was simply the rhythm of life. When I travelled between Japan and France as a boy, my family would take a ship liner, stopping in Hong Kong, Manila, Singapore, Saigon, Colombo, Bombay, Djibouti and Port-Saïd before reaching Marseille. Six weeks at sea — these are still some of my best memories. My favourite drawings then were ships and horses and airplanes, as if wandering was already part of my nature.

Except for my years studying in France, I never really stopped travelling. Over forty-five years I have been to more than seventy countries, always searching for an ‘ailleurs’, a ‘somewhere else’ that opens the imagination. I love France, but after three or four months I feel the need to go again. India suited me perfectly because it offered countless ‘ailleurs’ every day: new scenes, colours, sounds, people, unexpected moments. I felt freer there than almost anywhere else.

So yes, painting and dwelling in memory come from the same place in me, along with curiosity. When I am touched by a landscape, a room, an encounter, or a face, I quickly sketch it, then make small works – water colour, ink and wash, mixed media on paper - before going on to larger canvases with acrylic or oil. I slowly create a portfolio of works for each theme I have found interesting. I now have a whole bank of themes, drawings and paintings, maybe about a thousand sketches and works all together.

My family probably reinforced my inspiration. On my father’s side, for four generations, everyone was involved in the arts in Montparnasse or Saint-Germain: a sculptor, an art-book publisher, teachers, an architect. This heritage connects me naturally to the artistic spirit of Paris in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Writing is also part of the process. I have kept diaries and travel chronicles for years, often with sketches of the places or situations I found myself in — arriving in Dharamsala, the Jagannath festival in Puri, meeting a guru in Rishikesh, or doing yoga for three days in a huge stadium under Sadhguru’s direction. These memories, written or drawn, feed directly into my painting.

I often feel close to the lineage of traveller-painters-writers such as Pierre Loti, Claude Farrère, Paul Gauguin, or even Edward Lear and Richard Francis Burton on the British side — artists for whom travelling, observing, sketching and writing were all part of the same gesture.

As for nostalgia, it comes and goes. Sometimes it is a force, sometimes imagination or humour takes over instead. Melancholy often returns in the end — I accept it. Do I paint to remember or to keep something alive? Probably both. In painting, I choose the places and moments that moved me, to reinterpret them in my own way - never copying - with my twist, palette and mood.

Much has been said of your travels across Japan, Vietnam, India, Iceland and Africa, but your work does not appear as an ethnography or travel diary. Instead, these places blur and merge and enter a field of fantasy, with Goan rooms opening onto impossible seas and jungles murmuring with invented fauna. Where does the threshold lie for you between observation and invention? When does reality permit becoming imaginary, and what are the ethics of that transformation?

I tend to follow my instinct, or rather my natural drive as an emotional explorer. I usually choose my subjects according to three simple criteria. First, I need to be moved, intrigued or amused by a theme, a view or an encounter I have really experienced. Second, I need to find the subject — whether a landscape, a human scene, musicians, an interior, a jungle or a portrait — plastically attractive. And third, I look at the possibility of transforming or translating the scene into another realm, in my universe.

Let me give a few examples. I have always loved Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe by Édouard Manet. Everything in this painting moves me: the composition, the three characters, the forest background, the balance of colours and tones. I began by making simple copy-sketches. And then, suddenly, came the idea of transposing Manet’s picnic into an Indian jungle. The same composition, but with tropical vegetation, Indian figures, the mood of a monsoon clearing. This turned into a series of works.

Another example is my Ladakh series. I travelled twice across Ladakh, took countless photographs of gompas (Tibetan monasteries), and sketched them on the spot. From these pencil notes I moved to watercolours, and then to semi-abstract compositions on canvas. The landscape itself guided the transformation: Ladakh is majestic, mineral, spiritual, and for me it naturally called for semi-abstraction rather than literal depiction.

My experience in Bikaner, in Rajasthan, came out in a different, more expressionist way. One evening I stood in a bazaar at twilight, watching a paan walla (betel leaf shopkeeper) waiting for customers. The atmosphere felt strangely suspended, almost Hopper-like. I sketched the scene on the spot and later made a realistic yet expressionist painting of it, trying to render the stillness of the moment, in a street normally bustling with traffic and noise.

Mumbai’s Dharavi slums inspired yet another kind of transformation. It is one of the biggest slums in the world, extremely poor and dirty, yet I found the façade of a three-storey slum overlooking a sewage canal at night strikingly beautiful. I found it very colourful with a natural abstract composition, so I made a series of semi-abstract sketches and paintings full of colours, and eventually a large oil canvas of 100 × 150 cm.

When I work, I often remember a line attributed to Delacroix: “What one seeks in painting is not reality, but expression.” That sentence says it all for me. Reality is the starting point, but what matters are the emotion and references triggered in me. The degree of transformation then comes spontaneously. It depends on the subject, my bank of images, and my mood.

The ethics of transformation? I follow one rule only: to remain respectful. Even when I occasionally take a caricature-like approach, my intention is always to bring out and give presence to the themes and people that attracted me in the first place. I paint with empathy and with gratitude.

In your portraits of Brahmins, villagers, musicians and yogis, there is humour without caricature and reverence without idealisation. How do you negotiate the fragile space between empathy and representation when painting the human figure? What kinds of encounters, lived or remembered, allow you to paint these bodies not as types but as presences

My approach to the human figure depends on the subject and the emotion it creates in me.

For a strange reason I cannot explain, I had early on a fascination for yogis and swamis. As a teenager I drew yogi cartoons simply for fun, not knowing much about them. In India, I came across yogis on the road, during pilgrimages, in ashrams, stadium gatherings or even on TV, on guru channels! And I formed a rather mixed opinion about them. I was intrigued, I liked meeting them, I felt some of them seemed sincere, but many looked ambiguous, absorbed in ritual, their own image and influence. On the other hand, practising yoga in Delhi, Kerala or the Himalayan hills taught me a great deal. My Indian teachers insisted on proper asanas and pranayama and introduced me to the tradition of Krishnamacharya and his disciples — names often forgotten in the West. This combination of humour, fascination and learning naturally shaped my yogi paintings, which remain imaginary and playful.

With musicians I had a different experience. Indian classical music has moved me deeply. I have attended many concerts, admired great masters, and studied the sitar for seven years with a guruji. What interests me in painting music is the visual presence of musicians on stage: their elegant posture, the lights, the flowers, a reverent audience, the whole atmosphere, sometimes the bliss of the moment. Music is time; painting is stillness. I do not try to “paint rhythm,” but simply to capture the atmosphere and arrangement of the scene. From sketches made in concerts, I imagined recitals in Himalayan forts or Rajasthani havelis, and went further to explore semi-abstract cubist compositions, perhaps in an effort towards greater simplicity, even purity.

Portraits form yet another field. In self-portraits I allow every mood to appear — humour, nostalgia, irony or madness. I also paint family and friends in an expressionist way, often adding details that evokes their personal world. And I also exercise myself in spontaneous imaginary portraits. I let a face emerge from a loose sketch, in a succession of random hand strokes that I gradually refine to get a portrait, realistic, expressionist, cubist, in black and white or in colours. Recently I have enjoyed assembling some of these small fantasy portraits together on a single sheet, creating a collection of presences and moods.

In all these cases — yogis, musicians or portraits — I start from a real encounter. From there, the form may become realistic, playful or abstract depending on the subject and my mood. But the intention remains the same: to paint human beings not as types, but as a presence with an expression.

Your series inspired by Indian classical music seems to breathe with rhythm rather than illustration, as though the sitar's resonance has become a visual pulse across the surface. In your experience as both a painter and a sitar student, how does sound become colour and duration become form? Is there a synesthesia at work in your process, where listening is already a form of painting?

Before coming to India, I played classical guitar for many years. I reached a good level and enjoyed it very much but never felt the urge to sketch or paint anything related to guitar music. That changed when I arrived in India. Early on, I began sketching concerts and musicians on stage. Why? Because everything was new to me: the sound, the instruments, the atmosphere, and especially the extraordinary “mise en scène” of Indian classical music.

I remember one of my first concerts in Delhi, a late-night recital at India Gate. The stage stood in the middle of the vast lawn, under a white tent. Delhi’s entire world seemed to be there — politicians, businessmen, media professionals, civil servants accompanied by magnificent ladies in shimmering saris and pashmina shawls. The great master Pandit Jasraj was to sing. As in any Indian concert, the audience settled long before the musicians appeared, sitting or lying on white cushions spread across the ground. Then the musicians arrived, dressed in great elegance. They took time to tune their instruments, adjust the speakers, and light the auspicious lamp. Magic began there, before a single note was sung. Their quiet preparation, the expectation in the crowd, the winter night, the colours and fragrances — all of this created an atmosphere I had never experienced before.

Ever since, I have sketched and painted Indian concerts — not the notes, not the rhythm, not any idea of synesthesia — simply what I see. I paint the stage, the decorum, the atmosphere, the dignity of the musicians, and the unique bliss of Indian night concerts where performers and audience may spend hours, even the whole night, together.

Sound does not become colour for me, and time does not become form. For me music belongs to time; painting belongs to stillness. But the scene of music — the way musicians inhabit it — has inspired me deeply. That is what I try to capture.

Goa appears repeatedly in your work as a bridge between Portugal and India, between Western and Eastern pictorial languages, between history and reverie. You have lived in many places, yet Goa feels like a psychic centre. What is it about Goa that allows such a synthesis? Is it geographical, cultural or something more elusive, a rhythm, a temperature of light, an atmosphere of dreaming that continuously returns to you?

Goa is indeed very close to my heart. It epitomises for me a perfect “place in between” — halfway between Europe and Asia, between past and present, reality and reverie. In many ways it feels like a natural bridge between Japan, where I was born, and Europe, where I come from! Goa was a staging point on the long route to the Far East created by the Portuguese in the sixteenth century, and that atmosphere of passage still lingers everywhere in Goa.

For me, the connection is even more personal. As I was the first child in my family born in Japan, my mother gave me the second name François-Xavier, after the Jesuit Saint François-Xavier, who spent years in Goa before travelling on to Japan. His shrine still stands in the old capital, Panjim. In that sense, Goa has always felt like an emotional return — a mirror of my own wandering life between Japan and Europe, my past and present, my reality and imagination.

There is more. Just days before the first Covid lockdown in March 2020, I discovered the village of Chandor, formerly Chandrapur. There stand several magnificent Portuguese houses preserved almost unchanged for three centuries. Walking through these grand havelis — with their staircases, ballrooms, dining halls, four-poster beds, chandeliers, mirrors, old Goan furniture and even sedan chairs — one slips effortlessly into another time. Through the large windows, tropical gardens unfold, and beyond them, not far away, the Indian Ocean. Light and breeze move gently through the rooms, curtains, shadows and reflections constantly shifting. Standing alone in an empty ballroom, I could almost imagine the ghost of a naval officer dancing with a young lady.

I returned to France just in time for lockdown and found myself confined for weeks in a Paris flat. During that time, memories of Chandor became my inner refuge — a dream of seclusion not enclosed, but open onto gardens and sea. A dream of far-away freedom.

From these memories and photos, I began sketching and later painted a series of fantasy works titled Room with a View. They are inspired by the Braganza and Pereira houses of Chandor, filtered through memory, imagination, and perhaps also through my love of Matisse’s interiors on the Riviera. Goa is, for me, a place where inside and outside reconcile, carried by the nostalgia of a bonheur passé.

Your Icelandic series, with its restrained palette and vast solitary horizons, stands in striking contrast to your Indian works, which are dense with mythic vitality and colour. Yet both seem animated by the sublime, one through silence and the other through abundance. Do you see these bodies of work as opposites or as mirror images? What does each teach you about the human condition, about solitude and about awe?

There are indeed deep contrasts between India and Iceland, but also unexpected points of convergence. India is vast, crowded, full of people, movement, noise and humanity. Iceland, by contrast, feels small, empty, isolated, dominated by the sheer power of nature. At first glance, they seem like opposites.

Yet the more I travelled, the more I felt connections. Iceland and the Himalayas share a similar intensity: wild mountains, ice and glaciers, violent winds and storms, the feeling of extreme lands, of the end of the world. In Iceland, some glaciers or desolate seashores reminded me of ruins lost in the Rajasthan desert, or of Ladakh monasteries appearing as tiny spots in an overwhelming mineral landscape. In both places, human presence feels fragile and almost accidental.

I was also struck by the number of young Indian tourists in Iceland. They seemed drawn to the exact opposite of their own country — silence instead of density, emptiness instead of saturation.

What attracts me to Iceland is its remoteness — lost in the middle of the North Atlantic — its constantly changing climate, its raw horizontality. I am sensitive to its stories too: the life of cod fishermen, Pierre Loti’s Pêcheurs d’Islande, the Icelandic sagas. Iceland feels like another station on the road to extreme faraways — faraways I have come from and keep returning to.

So, what have I tried to paint there? I would say the same as in the Himalayas: mineral landscapes, the sheer force of nature, the strong and constantly changing contrasts of light and shadow, the feeling of immensity and solitude. And above all, the extreme fragility of mankind when confronted with wild, almost divine beauty.

Many viewers have remarked that your paintings suggest rooms that open onto other rooms and worlds that open onto other worlds. There is often a window, a doorway, a passage, a liminal space where one era, one culture, one emotion meets another. Is this architectural logic deliberate? Do you conceive of the canvas as a threshold, a ceremonial site where multiple homelands coexist? And what do you hope the viewer experiences when standing on that threshold?

Yes, I am very attracted to openings — doors, windows, mirrors, reflections in water. I like the idea that a painting can contain more than one space, more than one world. A mirror reflecting another room, or a forest appearing through a window, immediately creates a sense of mystery.

I think these pictorial “mise en scène” allow two worlds to coexist instead of one. They invite the viewer to imagine what lies beyond the visible space. In that sense, I probably work a bit like a storyteller. Like Alice in Wonderland, I enjoy the idea of crossing to the other side — through a door, a mirror, or a threshold — and letting imagination take over.

This is not something I conceptualise in advance. It comes naturally. I like inventing stories, and I suspect this taste for passages and in-between spaces is linked to my own wandering nature. Each painting is a small journey, and I hope the viewer feels invited to step inside and travel with me.

Your influences range widely, from Gauguin and Douanier Rousseau to Caspar David Friedrich, Hopper and Matisse, yet your paintings do not feel derivative, they create a syntax that is unmistakably yours. How do you absorb influence without imitation? Is influence a conversation with the past, a kind of correspondence or perhaps a lineage? And what does it mean for you to paint within a tradition while simultaneously inventing a personal mythology?

I accept the references you mention — Gauguin, Douanier Rousseau, Friedrich, Hopper, Matisse — and I would add Manet, the Cubists, and more recently the German Expressionists, Carl Lohse or Gabriele Münter, Edvard Munch, especially for their portraits.

I do not think of influence in theory. These painters have simply accompanied me for years; their work has become part of my visual memory, and I have added them to my own travel bank of images. So that on any given theme, for instance portraits, I keep image sources of both master works and my own images. It is from there that I decide to create a painting. I can be inspired, but I never copy.

Do I have my own style? Perhaps it lies in a personal way of combining drawing and colour in the service of imaginative themes. That alone suggests that a distinct voice exists, even if I do not try to define or claim it. I do not paint under any banner, nor with a message, an ideology or a constructed mythology. If there is a constant thread in my work, it is simply wandering — moving through faraway worlds with empathy, a touch of nostalgia, and often humour.

Across your oeuvre there is an underlying spirituality, not doctrinal but atmospheric. Yogis, musicians, animals, deities and landscapes coexist with calm inevitability, as if they have always shared the same world. Do you see your painting as a form of devotion? When you say you paint to honour the faraway worlds that continue to inhabit me, what kind of honouring do you imagine, remembrance, gratitude, mourning, celebration? And how does the act of honouring take shape in pigment, gesture and time?

My painting is certainly not doctrinal. If there is something that could be called spiritual in my work, it is not a faith or ideology. It is simply a matter of atmosphere — of presence — rendered through imagination.

Painting is my way of honouring the places I have travelled through and the people I have met. Not by documenting them, but by remembering them with gratitude. I paint what moved me, what stayed with me, and what continues to inhabit me — with empathy, interpretation, and sometimes nostalgia.

I like Pierre Loti’s note: « Je n’ai jamais voyagé que pour rêver. »

I could say that I have kept wandering to keep dreaming — and painting.

Ladakh Gompa over a mountain lake at night, 2019, Acrylic on canvas, 70 x120 cm

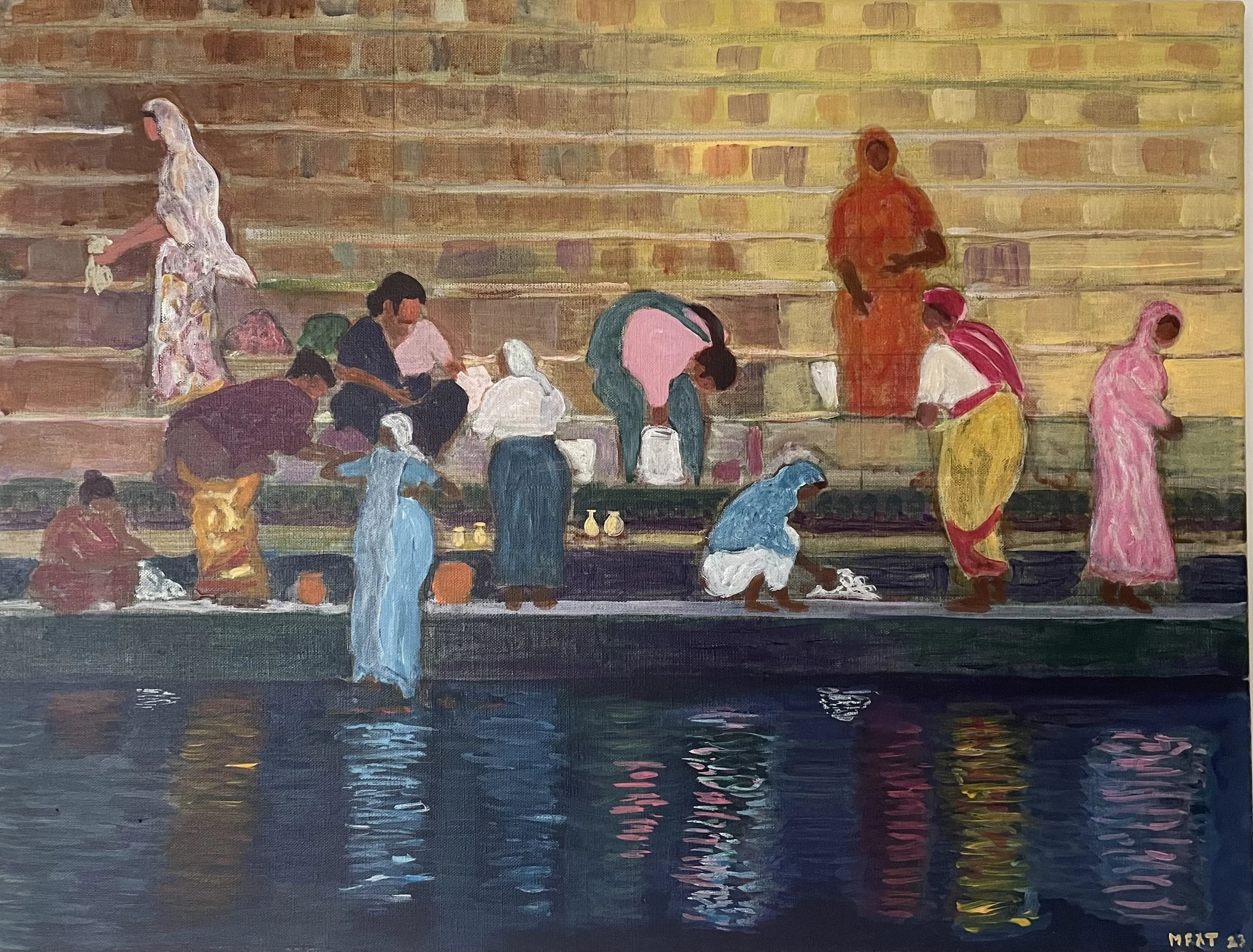

Benares, washerwomen on Ghats, 2023, Acrylic on canvas, 50 x 70 cm

Vietnam paddy fields, 2020, Acrylic on canvas, 51 x 76 cm

Memory of Halong bay II, 2025, Oil on canvas, 128 x 124 cm

Iceland revisited, Vik beach, 2023, Acrylic on canvas, 30 x 90 cm

Picnic in the jungle (after Manet le déjeuner sur l'herbe), 2022, Acrylic on canvas, 45 x 60 cm

Bombay Dharavi Slum at nigh, 2025, Oil on canvas, 100 x 150 cm

Nine men portraits, 2025, Mixed media on paper, 100 x 70 cm

Indian Jungle screen, 2025, Acrylic on canvas, 150 x 150 cm

The Music room (after Satyajit Ray), 2022, Acrylic on canvas, 100 x 150 cm

Sitarist in blue over green, 2025, Acrylic on canvas, 101 x 76 cm

Bikaner street at night, Acrylic on canvas, 101 x 76 cm

Goa Room with a view II, 2023, Acrylic on canvas, 92 x 65 cm

Jungle Triptych and me, 2023, Oil on three canvases, 150 x 300 cm

The artist studio, 2025, iPhone photo