Interview with Ashley Gray

https://artofagray.squarespace.com/

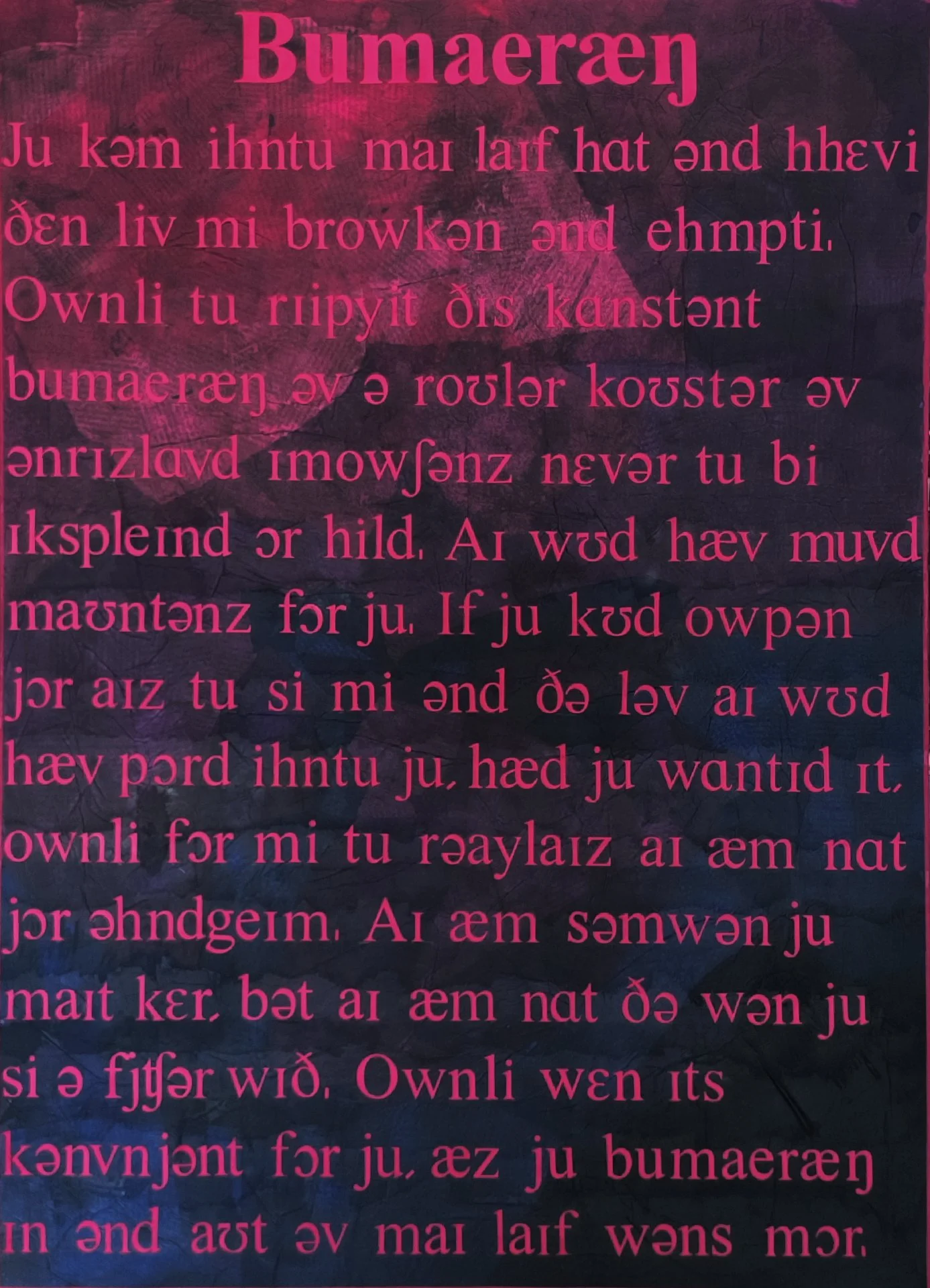

Ashley, your work often stages a moment suspended between emergence and dissolution, an image that seems to have just ended or is about to begin. How consciously do you choreograph this temporal ambiguity, and what does that threshold moment allow you to express about emotional states that cannot be articulated in linear narrative language?

These in-between moment or element is just how I see it, its like trying to connect the vision to the emotion and for me there is something about that moment, almost like the reason the beginning and end have meaning is because of the middle. The middle is where the defining action or experience happens, where the emotional charge lives. I’m drawn to getting close to that moment, because that’s where the emotion feels strongest, where the shock is. It is this shock that people understand that wakes them into partly seeing something I am trying to say.

I hope to show that emotional states are far more powerful and complex than we usually acknowledge. Like many artists, I feel compelled to express something that matters deeply to me, even if I can’t fully articulate it in a straightforward narrative. It feels like whatever I’m trying to say lives inside the body of my work itself. I don’t completely understand what it is yet, or whether I can ever fully express it, but I know I have to try. I think many artists feel that same conviction about something they sense but cannot name.

Much of your practice revolves around the idea that grief, loss, and internal dissonance are shared human terrains even when experienced privately. In shaping digital figures that echo universal vulnerability, how do you negotiate the tension between the deeply personal origins of your imagery and your desire to relinquish authorial control so that each viewer may read themselves into the work?

For me, there are two parts to this. First, I don’t try to force meaning onto the work. I don’t really understand that approach. I spend more time trying to communicate something universal rather than weaving clues about my personal story into the images. The privacy of my life is separate from the work, I would rather not expose it, and I don’t think it’s what people are looking for even in images like 'The Swarm' or 'Mercy' what happened is not important at all only what the viewer thinks or feels. So I don’t lean in the direction of trying to lead people about my life I feel only my reflections matter not so much who I am.

The second part is newer for me. The point of my work is to connect with people through resonance. I meet the viewer through the image somewhere in the middle, I want people to feel something of themselves in it rather than focusing on me. I don’t know my audience personally, they don't know me, we are at distance from each other, it allows the work to stand on its own. For some people, art is about the artist, but for me, it’s about creating space where the viewer can read their own experience without being directed by mine, I'm not trying to connect with some alter reflection of myself, I'm trying to connect with the people who understand.

Your practice is notably unconcerned with the orthodoxies of digital craft, such as poly count, modelling conventions, or aspect ratio hierarchies, yet you use the same technological tools as artists who prioritize these systems. How does working artist first, rather than as a three-dimensional technician first, enable you to disrupt expectations within digital practice, and what do these disruptions reveal about the possibilities and limitations of technology when subordinated to an emotional or philosophical agenda?

I don’t know if I’m disruptive in a deliberate sense, but I do feel strongly about the art, the essence of things. Because of that, I’ll remove or adapt anything that gets in the way. Technical artists are often bound by their systems and are very skilled at fitting the art into the technical box, though I have training to do this I have the freedom to expand that box or remove it entirely.

For me, the real possibility lies in showing the unreal, or giving more clarity by bending reality. I think about films and games that do this, they use their medium to shift perception and deliver grand ideas. I hope to do something similar. The works that stay with me, games likeBioshock,Stalker or filmsAnnihilation, orSunshine, have this strange gravity because they touch something universal so strongly. They express it through a personal style but it still feels widely understood, rather than obscure or chaotic. That’s what I want digital tools to do when they’re subordinated to emotion or philosophy. To make space for moments that feel larger than the technical framework that produced them.

Works such as Blue Heart Forever and Distress Signals articulate what could be described as a luminous despair, a darkness pierced by a single defiant point of connection or endurance. How do you conceptualize light as both a symbolic and structural device in your digital environments, and what does its deliberate scarcity communicate about the fragility and resilience of the human condition?

There are two parts to this: light as meaning, and light as technical perception.

I’m naturally good at infusing meaning into things, and light is one of the strongest symbolic tools I have. People often notice how I use and control it to tell the story of the image. Everything holds meaning for me, everything connects to something else. That’s just how my mind works, ideas filter in and light is integral to they way they are communicated to me.

Then there is technical perception, which is different from skill or training. It’s more about how I process the world and how my technical understanding merges with my emotional perception. For me, emotion runs so deep that it easily binds itself to light. That intuitive connection is a big part of why I make the kind of work I do. I’m learning that not everyone sees or feels what I do. Even on a basic level light is warmth transferred, it’s life for plants and humans, it’s hope, it’s clarity, but it can also be fragile or overwhelming. These symbolic contradictions are countless, and I can hold many of them at once when building an artwork.

The deliberate scarcity of light matters because darkness equally carry's gravity, yet light is essential. We feel it. That simplicity gives it power, like air. Light has immense thematic force. We all know stories of people doing impossible things when someone they love is in danger: ripping off a car door, swimming miles to save whoever. That is a form of light. I use its power to communicate. I don’t fully understand its gravity either, but I can feel it more? Or something.

You often describe your intention as creating images based on sensations that are felt but difficult to explain, and that the digital medium allows you to sculpt thought rather than illustrate form. Can you describe how digital layering, distortion, and abstraction allow you to materialize sensations such as memory, isolation, or shifting identity in ways that traditional media might not?

I’ll try. I feel more connected to sensation and emotion than to concrete narrative, and because of the way I perceive things, 3D is a strong connective device for me. Ideas flow more easily there. Part of it is skill, I’m always frustrated with my skill level, but part of it is that if I were only drawing on paper, the work would feel less compelling to my mind. In 3D I’m building a scene with depth, and that depth holds a kind of gravity for me. I can move the camera, adjust the environment, and refine details until they align with the emotional weight I’m trying to reach. Even in 2D, I can zoom in to pixel-paint lightning or fix a single strand of digital hair if it feels wrong. It’s always emotion over technicality.

Materialising sensation is difficult, but I’ll try to explain it. I spend a lot of time bending and distorting forms until something matches the intensity I feel. The 3D realm gives me a mathematically grounded reality to push against, and I shape it until it turns into something emotional. Digital tools let me crystallise the real and twist it into the felt almost simultaneously. Traditional media doesn’t give me that same kind of spatial grounding. The 3D world feels like a game space: real but unreal, stable but flexible. That duality calms my mind and opens something creatively that traditional media can’t. It’s like asking a painter to write a book, creativity can transfer, but only through mediums that match a person’s temperament. I can feel the compatibility with digital space, and I’m sure others sense that with their own mediums too.

Your biography includes an unexpected chapter in which you worked long hours in a cold Chinese meat factory immediately after completing a master's degree in Games Art. To what extent did that experience, its physical conditions, its repetition, and its stark contrast with your training shape your understanding of what art is for? Do you see echoes of that period resurfacing within recurring motifs of endurance and human fragility in your work?

Working in that factory didn’t change my view of art so much as confirm what I had already learned through reflection. Like most my seed came from childhood, from moments where people said things would be fun or hopeful when they obviously weren’t. Very early on I felt that the world contradicts itself too easily to be trusted. College and then university were the first places where 'the system' tried to pull me toward hope with real gravity but I was very guarded.

When I graduated and fell straight back into old patterns no matter how much I tried, no job, no future, and then suddenly a meat factory after all that endurance, it didn’t feel random. It felt like confirmation through experience a familiar illusion of a vision, alien to me. The world kept telling me I was wrong for feeling the distance I felt, to me my fall proved I wasn’t.

That job sharpened what was already inside me:, the endurance, the refusal to just die whatever place I’m put. My “art-self” didn’t come from escape but from something closer to a cold vengeance. The distance, the fragility in my work didn’t originate there, they were just amplified. I had known them emotionally long before that period.

The name Human functions as a conceptual filter that strips away biography in favour of universality, yet the digital bodies you construct, hands reaching, hearts glowing, figures suspended between void and illumination, seem rooted in intimate emotional experience. How do you reconcile anonymity with confession, and in what ways does the erasure of self intensify the autobiographical presence within your work?

The name Human strips away the surface details people instinctively use to categorise others, gender, age, biography, because all of that distracts from the emotional space I want the viewer to enter. It’s a way of saying: “I’m just another person. When there is no “me” to look at, the viewer has to sit with the art itself. It becomes confession without the shield of identity.

Human is a layered name for me. It’s a code, it’s a refusal of labels, it’s an apology and a declaration of fragility “I am only human”, and it’s a universal stance that all humans share the same core condition of existence. It’s also a kind of defiance against the universe. If you strip me down, I am simply that: human. I want the work to be encountered on that level, without escape routes or excuses.

Paradoxically, removing myself intensifies my presence. The work has more space to carry my emotional frequency without me as a distraction. Anonymity doesn’t mute the autobiographical element it amplifies it, because the emotion has nowhere to hide. It becomes universal because it’s honest, and personal because it’s unprotected. This requires a kind of disconnection. Sometimes I ask myself, “how can I be sure it is wise” Not in the sense of being provocative, but in the sense of exposing something true. As my audience grows, the number of things I feel it is “wise” to show becomes smaller.

Humanis not a mask. It’s the space where my inner world becomes visible without distraction. I’m not my name or my clothes, and I’m not interested in explaining a backstory. What matters is letting the viewer know: I feel it too.

Many of your compositions frame the viewer as an implicit participant, as though they are observing an event they are emotionally implicated in rather than simply witnessing. Can you speak about your approach to viewer involvement and how you engineer a gaze that does not merely look but becomes part of the emotional architecture of the scene?

It’s hard to explain because there’s a lot going on, but I’ll try. Viewer involvement starts with the position you occupy in a sense, so perspective is crucial. The placement of the camera in 3D space defines the viewer’s position and carries much of the emotional weight of the gaze. Bending reality helps the perspective match what I perceive.

For example, in Blue Heart Forever, many people assume the hands are my own, but the image is experienced from the viewer’s position as I see it, not as I am. Similar to a dream: you always occupy viewpoint in it, that placement defines the emotional gravity, and it’s one of the single most important elements. Everything else in the composition shifts depending on it, and the camera only moves for clarity in the final image.

The gaze itself is a combination of factors, overlapping with viewer involvement. Colour is extremely important. People often think colour just carries emotional energy, which is true, but it also helps reinforce perspective, highlight important elements, and build narrative. Perspective intensity is equally critical push perspective too far and the image collapses; too subtle, and the gravity is lost. I think so much of it as constructing the narrative through compositional elements.

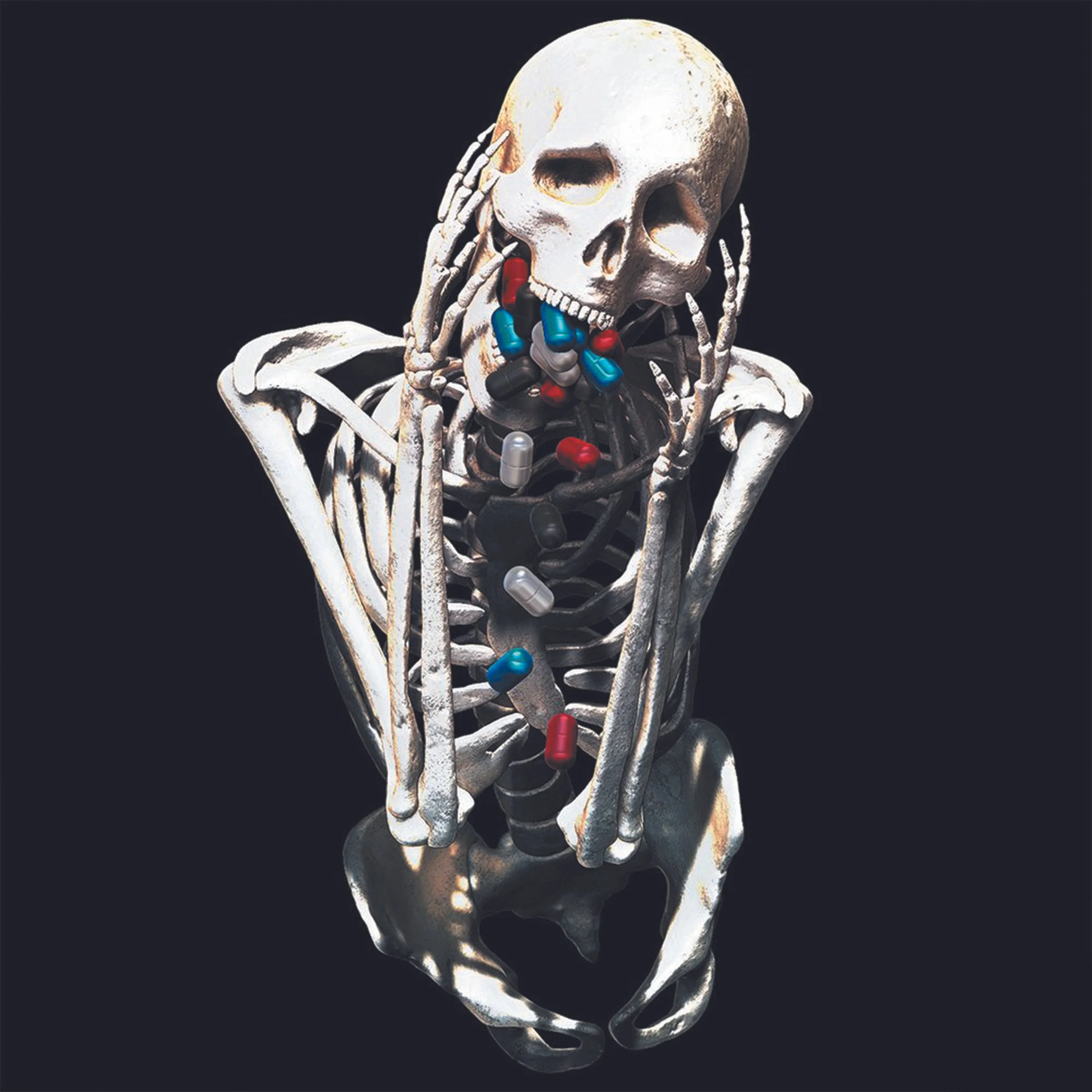

For instance, in Distress Signals there is a single child’s hand, in Pins, only the honour pin glows, in Medicine, the pills appear clinically clean in contrast to the skeleton. You might not consciously notice these details, but your brain scans for things and picks up an intention. All of these elements together: perspective, camera placement, colour, compositional focus create the gaze and draw the viewer into the emotional architecture of the scene.

Your images operate like psychological allegories populated by minimal environments, symbolic objects, and bodies caught in impossible gestures. How do you consider the grammar of symbolism within the digital space where the languages of myth, gaming, futurism, and spirituality converge? Do you cultivate ambiguity intentionally as a strategy for interpretive openness, or does ambiguity arise naturally from your process?

For me, symbolism doesn’t come from a predefined system, it comes from the way my mind naturally forms connections, shaped by personal experience and temperament. My brain is always seeking symbolic constructs that can carry multiple meanings at once, almost like an internal integrity test. Only symbols that feel expressive, flexible, and emotionally charged rise to the surface. I sit with them, feel their weight, and if their meaning holds strong across different layers, I use them. Anything can become symbolic even a crisp packet, but using it to communicate gravity and clarity is not easy, I used a hat once, just a hat alone, a long time ago.

I feel the emotional charge of a symbol before its exact meaning. Often the symbol arrives unconsciously, and reasoning catches up over time, layering understanding gradually like a processing phase. Because of this process, ambiguity naturally enters the work. At the same time, I also cultivate ambiguity intentionally. The way I frame and position a symbol is as important as the symbol itself. Its placement becomes a device to open multiple interpretations rather than close them down.

In recent years, your work has circulated widely through digital communities, creative platforms, and international exhibitions, yet you emphasize that recognition should never overshadow the collective human thread that runs through your practice. How do you maintain a sense of groundedness and shared vulnerability within a digital art ecosystem that often prioritizes spectacle, aesthetic perfection, and personal branding over emotional truth?

I stay grounded by returning to the emotional origins of my symbols. They are like fractures of my world, and I return to that world again and again. My work begins in vulnerability, often before I fully understand its meaning myself, and that keeps me connected to something human rather than performative. There’s a sense of knowing myself in at least some of my work. My artistic choices are not so much about self-discovery but reflection.

The digital ecosystem often rewards spectacle and personal branding, but those forces do not guide my decisions. Like gravity, some spaces naturally align with my style, and the audience that resonates gravitates toward me. All I can do is put out a pulse. I try to create from a place that isn’t about being seen but about being honest, to be witnessed. I remind myself that the work is a conversation, not a display.

The moment I start making images to satisfy the digital gaze, or any gaze but my own internal one, the work loses its integrity. It probably won’t carry the feeling, the essence fades, and the process becomes aimless. There’s no reason to attempt a paint up if the image hold little internal gravity.

Be Brave, Digital, 2020

Blue Heart Forever, Digital, 2017

The Luminous Stage, Digital, 2025

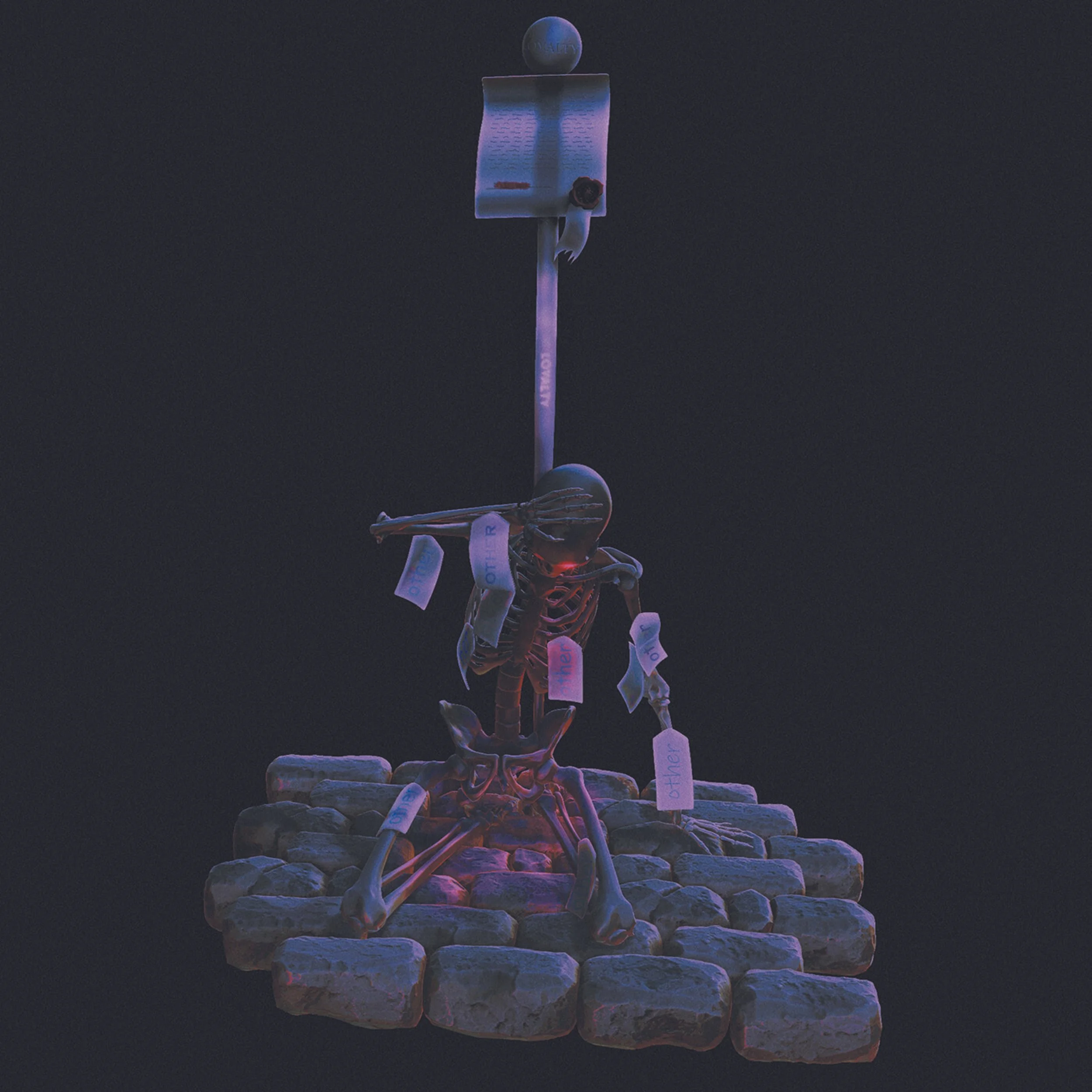

The Swarm, Digital 2020

Disheartened, Digital, 2020

The Persecution Principal, Digital, 2019

Are you Sure, Digital, 2025

Medicine, Digital, 2020

Never More, Digital 3D, 2015

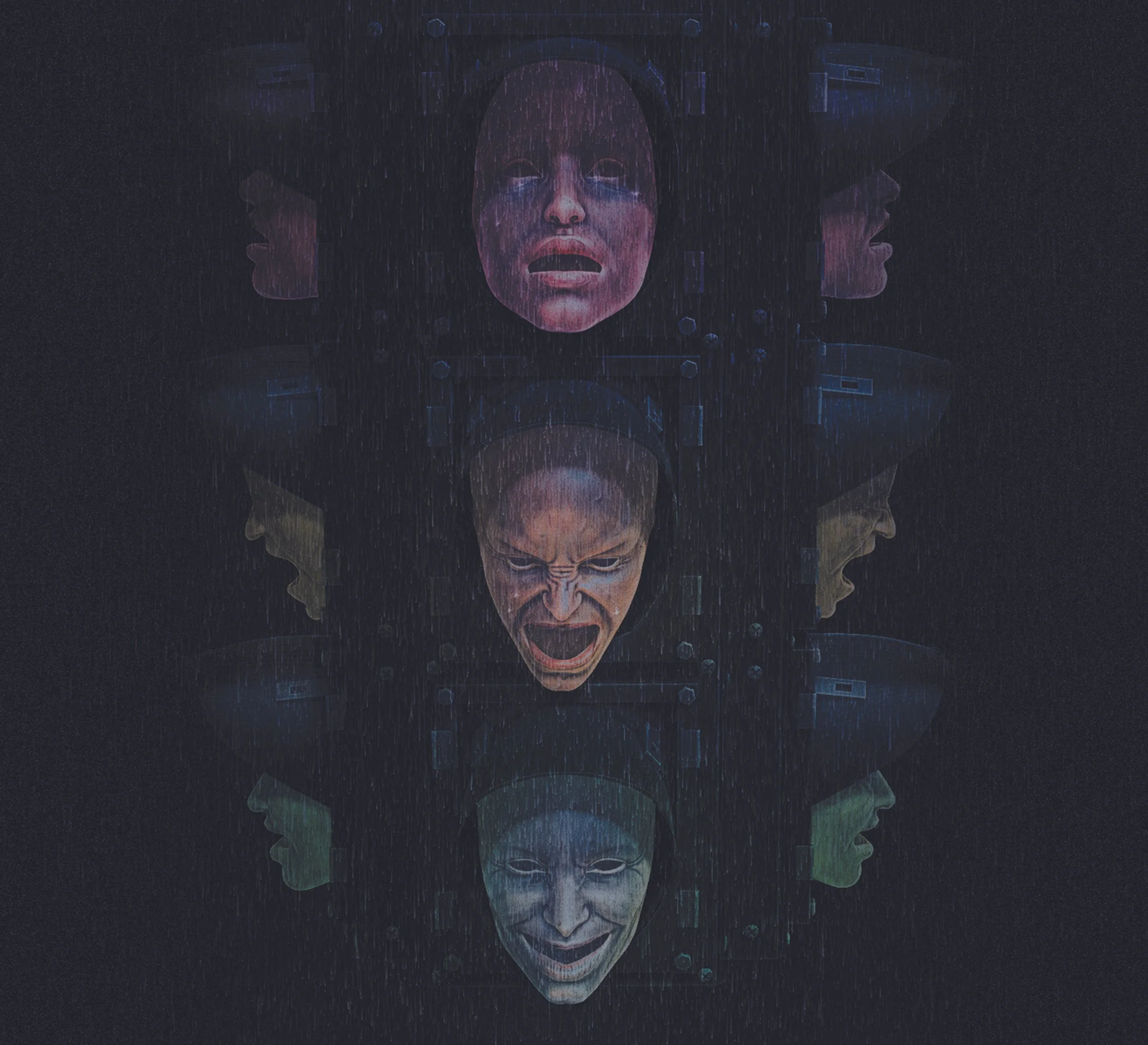

Traffic Lights, Digital, 2020

Black Star Children, Digital, 2018

Distress Signals, Digital, 2020

Ethereal Blue, Digital, 2015

Dangerous Games, Digital, 2025