Interview with EJ Lee

https://www.ejleesartwork.com/

EJ Lee is an interdisciplinary artist who transforms language into physical form. Her work often begins with autobiographical poems that explore experiences with dyslexia, trauma, and healing, which then shape the materials, colors, and forms of each piece. From sewn works to wearable garments and installations, her practice turns the instability and imperfections of language into a method for creating meaning.

Lee’s work asks viewers to slow down and engage, experiencing the weight of language both emotionally and physically. She embraces mistakes, misreadings, and unconventional syntax as sources of insight, allowing vulnerability to guide both the making and the viewing of her pieces. By blending craft and concept, Lee creates work that is intimate, deliberate, and grounded in human experience, inviting audiences to reconsider the ways language shapes perception and identity.

Your works often begin with language at the threshold of breakdown, misreadings, phonetic detours, repetitions, and slips, which you then rebuild into tactile forms. Could you speak about the moment when a mistake becomes a productive material, not merely a disruption of clarity, but a kind of latent architecture in its own right? How do you recognize the shift between error and meaning, and what does that moment reveal about authorship, control, and the body’s relationship to language?

The moment I recognize a mistake and turn it into something useful comes straight from my own experience struggling with English. I have always wondered why words are spelled one way rather than another, and felt my way of spelling just as valid. English is full of arbitrary and often contradictory rules, and it is not always easy to navigate.

Figuring out the difference between a mistake and something meaningful has a lot to do with phonetics. As a child, I was extensively taught phonics until it became almost second nature, but even then, some words simply do not follow the rules. These frustrations were not something I thought would become part of my art practice, but they ended up shaping it. During my MFA, a random assignment about art and protest reignited my obsession with dyslexia and the complexity of language. I realized that misreadings, slips, and phonetic detours are not just errors; they are material and powerful.

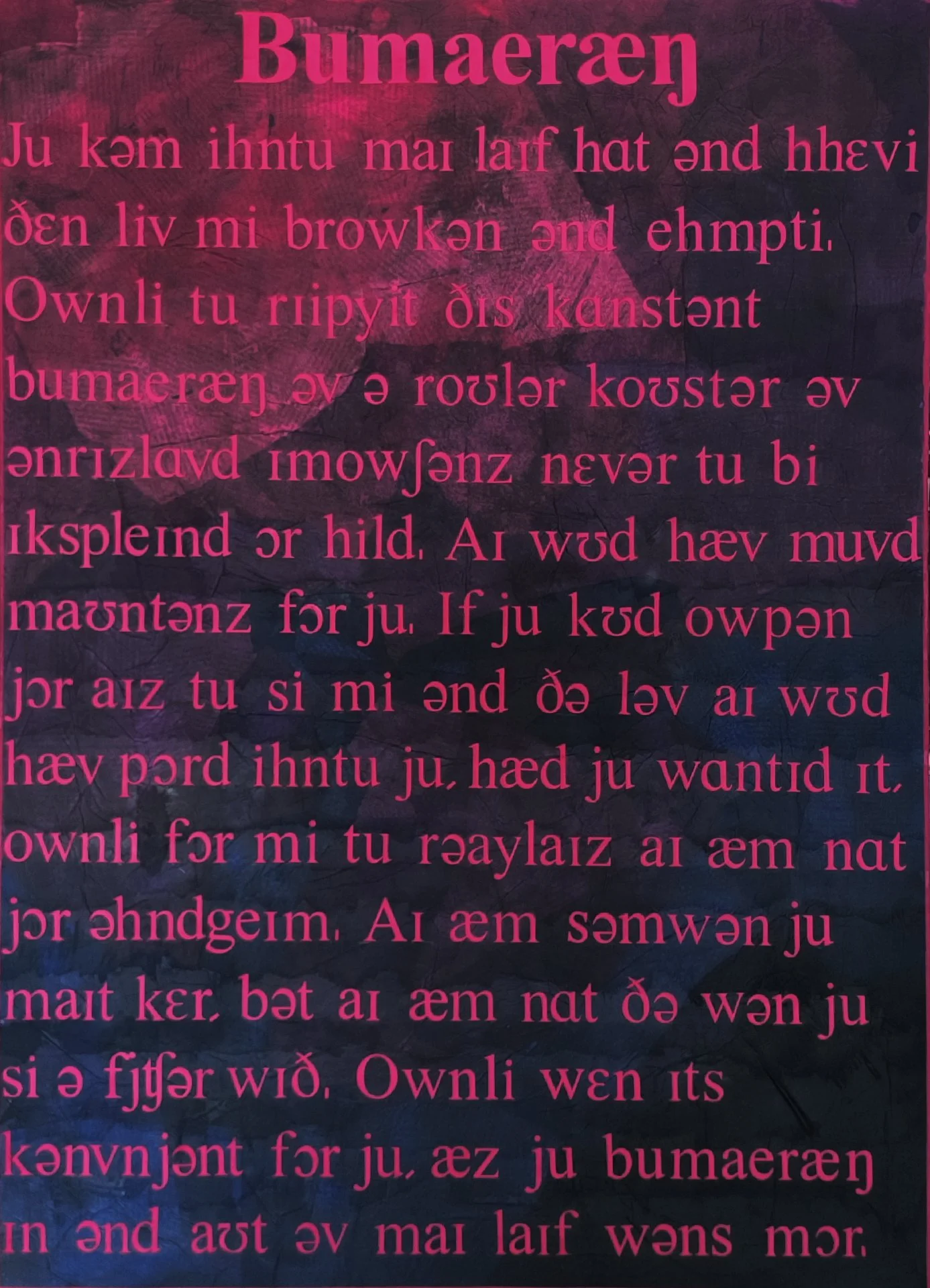

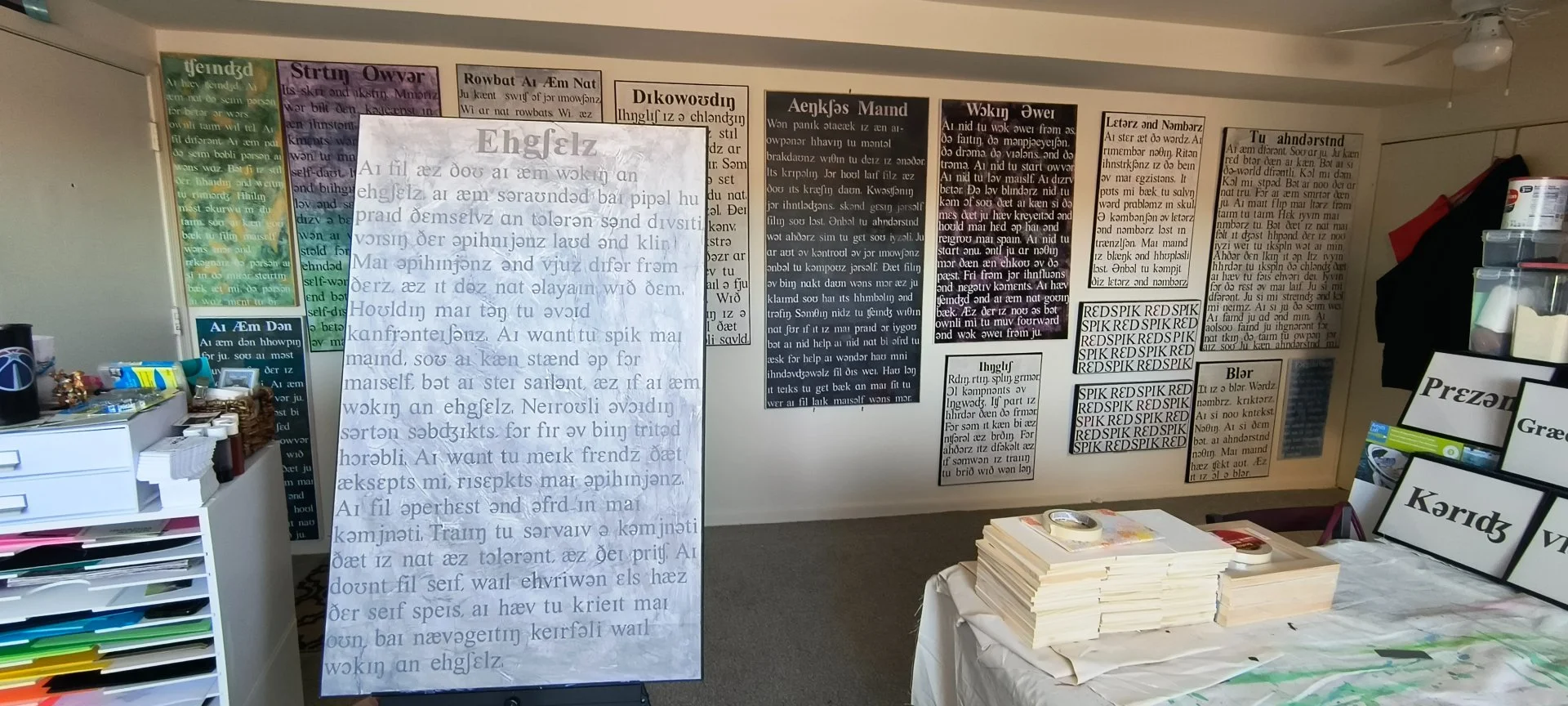

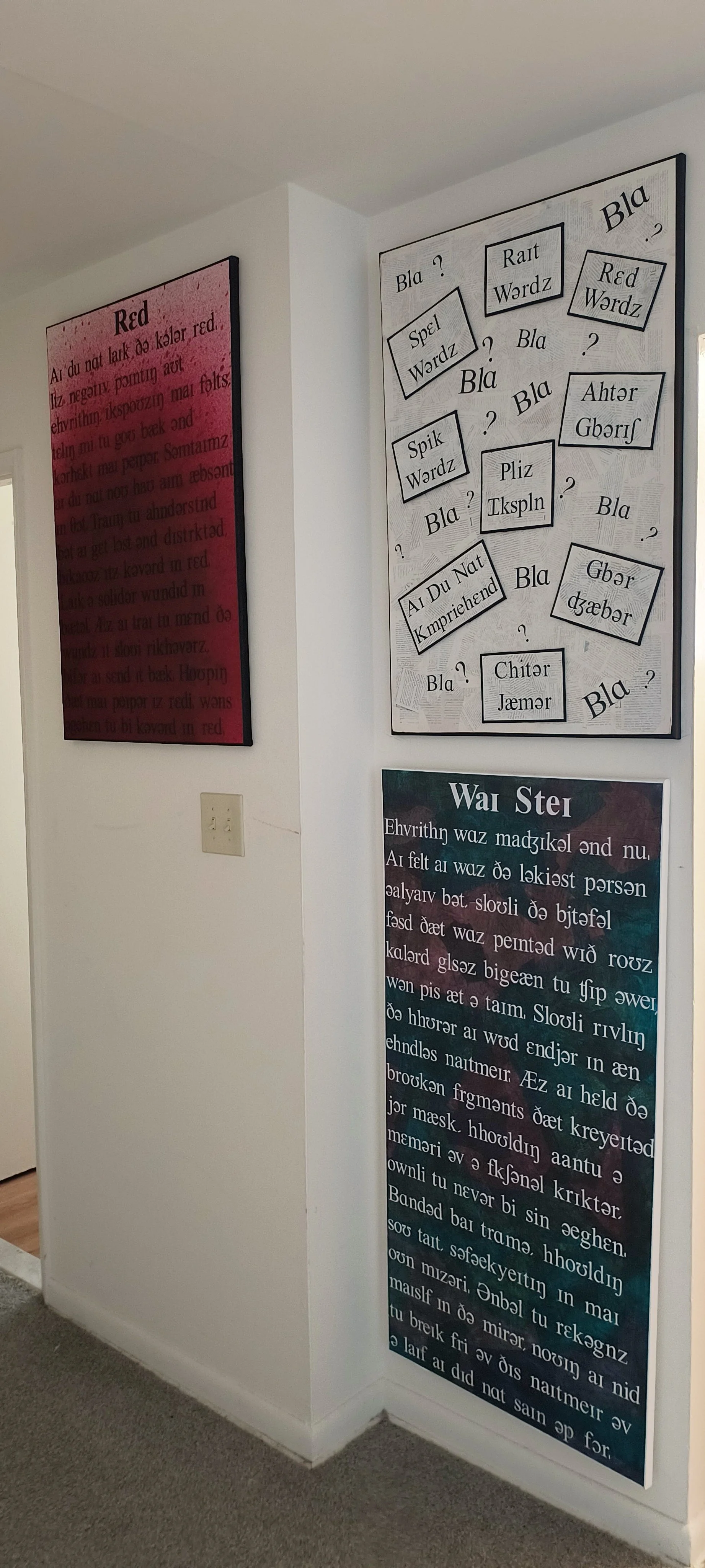

For example, I write poems using the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) in Times New Roman. The font feels familiar, but some of the characters are foreign, creating a push-and-pull effect to illustrate the frustrating aspect of struggling to read, much like someone with dyslexia. That struggle becomes the point. Mistakes become the structure, the architecture, of the work. The act of decoding mirrors the body’s engagement with language, and changes how the viewer experiences reading.

I am not the only person who struggles with English, but through my work, I invite people to see language differently: something living, complicated, and sometimes messy. What starts as a mistake can become meaning, and in that process, control and authorship are shared between the text, the body, and the mind.

In many of your pieces, the stitched line functions simultaneously as repair and inscription, mending a wound even as it produces a mark. How do you think about sewing as a form of writing, and conversely, about writing as a form of sewing, an act of binding, suturing, and rethreading the self? Does the act of stitching carry an emotional or temporal residue, almost like a diary of the hand moving through difficulty?

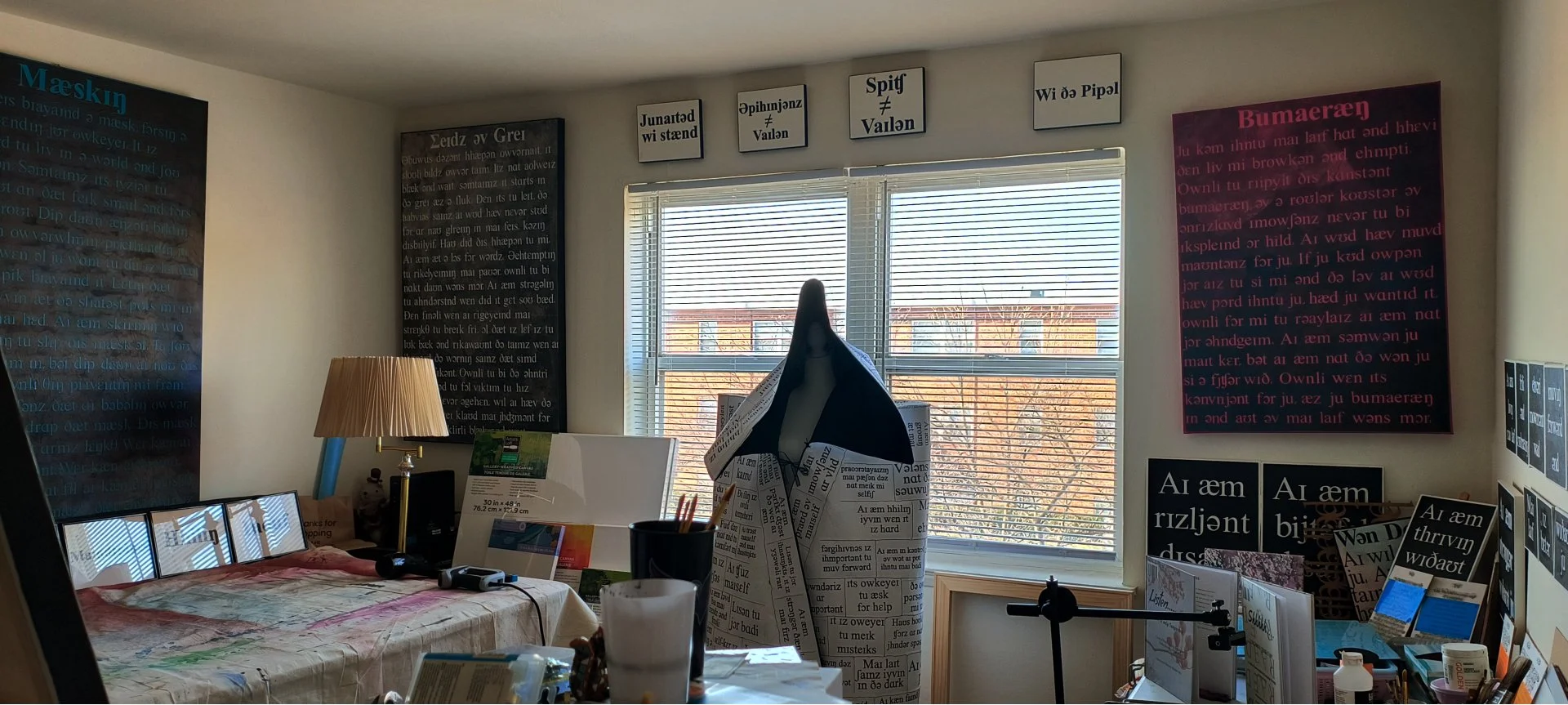

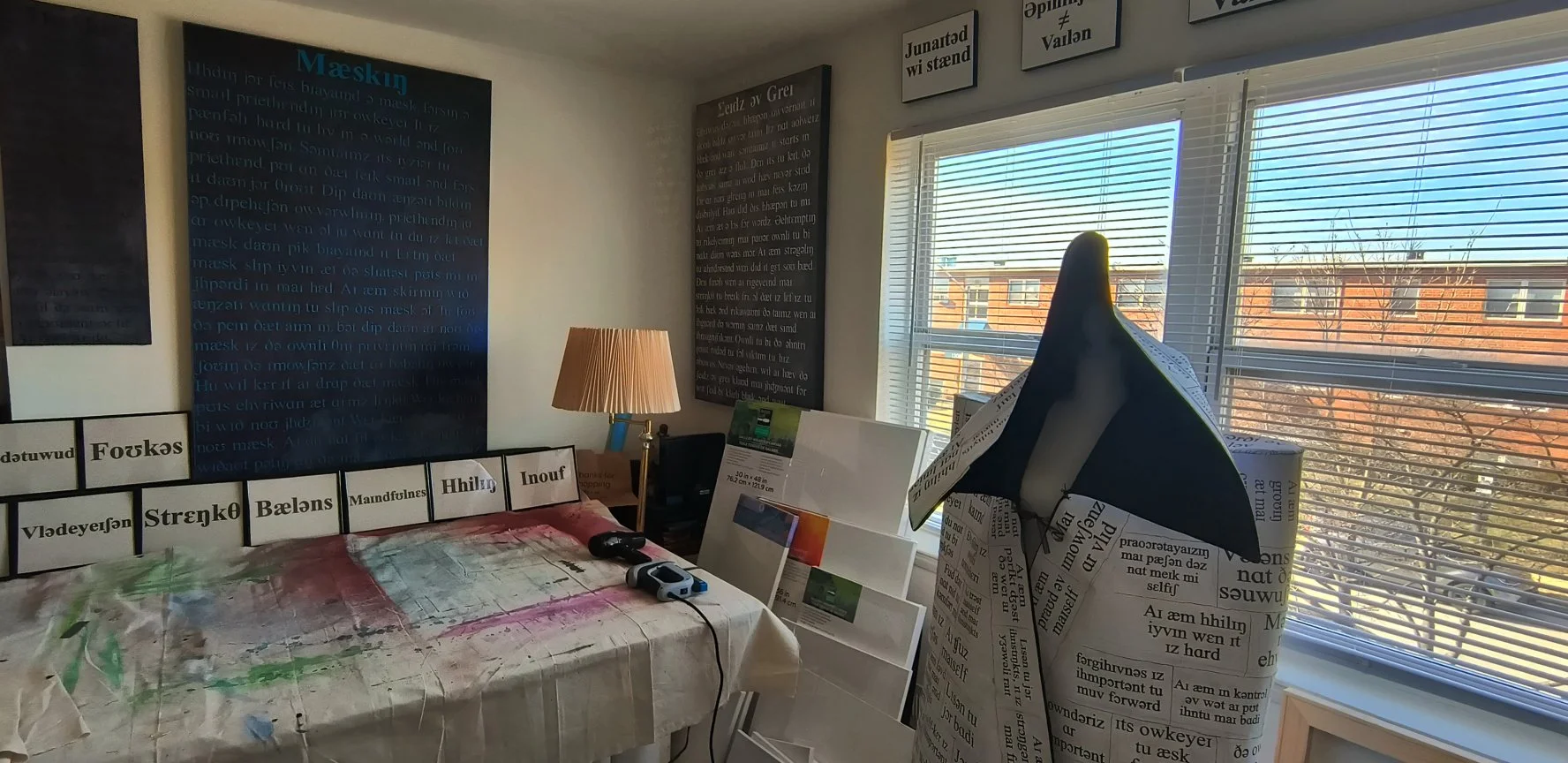

There is a certain quality and intention when sewing by hand versus using a machine. There is a presence and residue left by the artist’s hand when sewn manually. Through the process of hand-sewing, the Affirmation Cloak became a kind of healing journey. I was literally connecting pieces of text, each with a different affirmation, building them into one singular garment that could be worn.

While sewing the hundreds of individual affirmations, I was unsure what the final form would take. After sewing about twenty together, the involvement of my body, enveloped within the affirmations, led me to a conclusion: rather than creating a tapestry effect, I wanted to wear the affirmations as a shield. Part of my process is trusting my instincts and the inner voice in my head to guide me. The idea of hand-sewing as a form of writing is intriguing because it creates a repetitive motion that can be soothing for the mind, with each affirmation building on the others to form a unified work.

The imperfections of sewing paper together reveal the tumultuous and uneven nature of healing itself. The Affirmation Cloak became a form of documentation, a physical record of a process that started with the simple gesture of piecing myself back together. Over time, it grew into something that envelops the wearer, creating a protective shell of positivity.

Your wearable forms, the cloaks, the flags, the garments, introduce the notion that language does not simply surround the body but is carried by it, weighted and performed. What changes in meaning when language becomes something you can physically wear, rather than read? In those moments, do you imagine the viewer or participant becoming a reader, a witness, or a performer within the text?

In a way, language is larger than life because it is everywhere in our daily lives. The amount of text and even font that your body encounters daily is overwhelming and draining, to the point where, as a dyslexic person, it can be overstimulating. By making a wearable garment, I can show the literal weight of not only words but language itself. It becomes a conversation that many individuals do not consider until it confronts them. By reimagining language as a body or a life in its own right, one that visually or physically carries weight, the viewer’s experience of language changes, as it is seen as a material rather than simply a human construct for communication.

The concept of written language is a human construct, which became a focal point during my MFA program. I examined the shapes of the alphabet’s characters, which are abstract and arbitrary. By moving beyond books and signs into wearable garments or even poems, the interaction shifts. Text becomes a language of its own, arbitrary and redundant to the point where one must question its conventions. By shifting the experience of text and language in this way, I aim not only to examine the English language as a whole but also to invite the viewer into this discussion.

The viewer is an integral part of completing the work. Their interaction depends on their patience and their willingness to slow down and attempt to read the text, fully engaging with the struggle of reading. I am asking the viewer to become an active participant, whether interacting with a wearable garment or one of the poems. The viewer’s participation is the final stage of interaction with my work.

Dyslexia in your practice is not treated as a deficiency, but as an engine, a generator of alternative syntax and perception. When you follow the wrong turn in language, rather than correcting it, what forms of knowledge arise? Could we understand dyslexia here not as a limit, but as a methodology, an epistemology, through which the instability of language becomes visible, touchable, even liberating?

Using dyslexia as a lens, or even as a viewpoint, is my way of flipping the idea of normalcy. Instead of treating dyslexia as a deficiency, it becomes a way of thinking and perceiving that sheds light on alternative forms of understanding. I embrace the wrong turns as catalysts for inspiration. Even though dyslexia is common, it is still overwhelmingly misunderstood as a learning disability, which leads to misconceptions and stigmas that people assume magically disappear once someone turns eighteen. What often gets overlooked are the strengths that come with dyslexia: the ability to think three-dimensionally, to problem-solve in unconventional ways, and to see patterns that others might not notice.

As much as I use language as a material to explore and reinvent, this practice also becomes a form of advocacy for people with dyslexia. I am not the only artist or person who is dyslexic, but this lens, combined with my focus on language, adds a conceptual complexity that places the viewer in a position where they confront the reality of this perspective.

In a way, my dyslexia becomes the methodology. It changes how information is experienced, interpreted, and accessed. Misreadings or misspellings become part of my research process; they reveal the instability of language and open new pathways of meaning. That is the kind of knowledge I work from.

The materials you work with, paper, thread, fabric, fragment, repetition, are often modest, domestic, and intimate. Yet the works themselves carry a monumental emotional weight. How do you negotiate the tension between softness and severity, between the tenderness of handcraft and the hard architecture of meaning? Is this duality part of what gives the work its ethical charge?

That is an interesting observation. I embrace the idea that the concept or the artwork should dictate the materials I use when creating my works. Sometimes the materials themselves carry meaning, which leads to purposeful choices in both the materials and the colors I choose. The tension between softness and severity in my work comes from that mindset, a focus on material as a vehicle for concept, which has been instilled in me since my undergraduate program, along with an interdisciplinary approach. There is also a sense of minimalism, or "less is more," which can be extremely difficult to achieve.

In my work, there must be a balance between craft and fine art. Craft is only recently being recognized as a valid art form within the fine arts world, and my practice exists on that fine line. If I lean too far in one direction, the work risks losing its impact. I use materials that ground me, allowing the concept or message to come through clearly rather than overloading the composition to the point where the intent is lost. The purposeful tension between softness and severity allows the work to stand on its own and gives it the voice and ethical charge it needs.

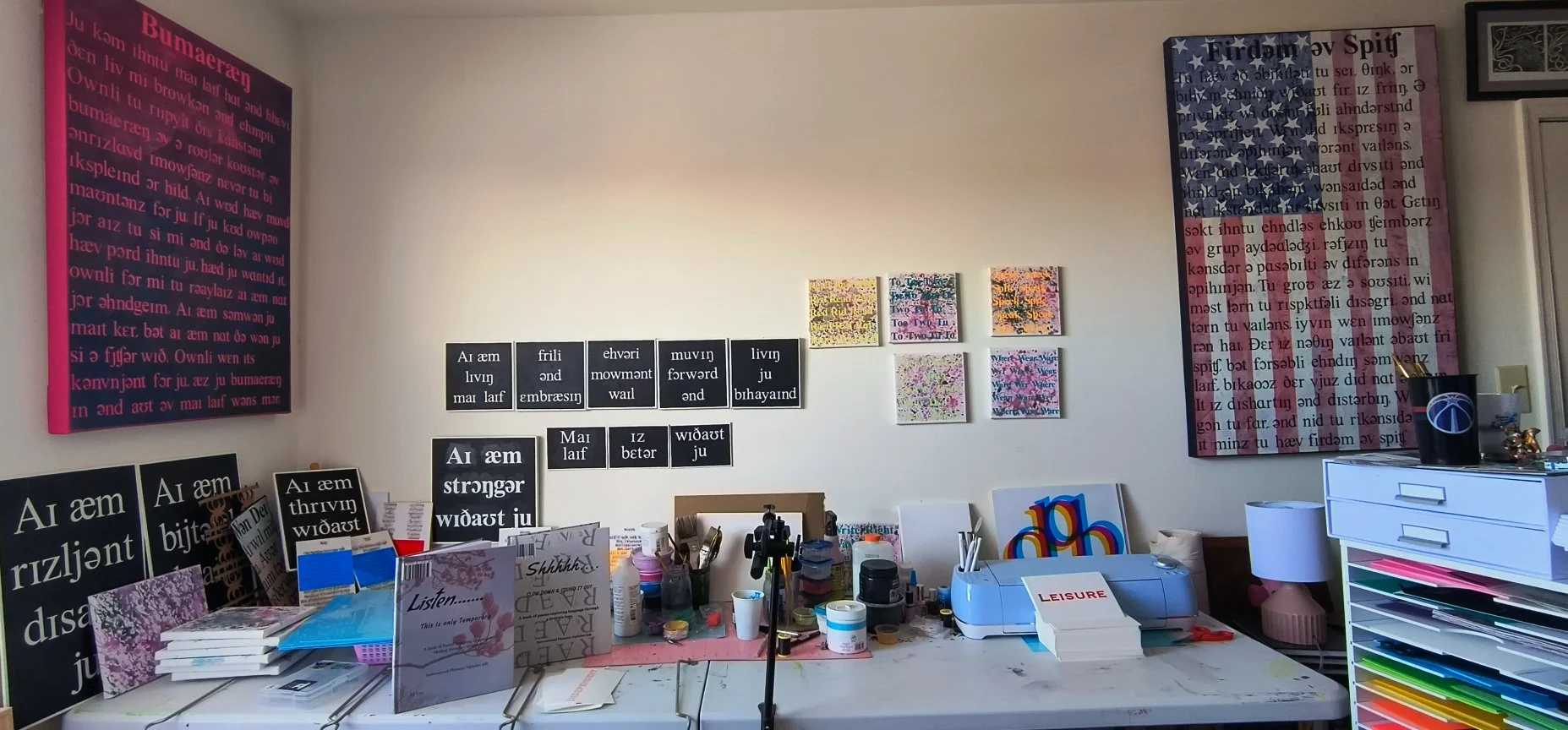

To reference my own work, my IPA poems on canvas, especially those about healing, exemplify this tension. The poems themselves are emotionally charged and explore themes that are often uncomfortable to discuss openly. I keep my personal life private, but for about a year, my practice and personal experiences overlapped. While this could feel discomfiting, using the IPA format and deliberate color choices allowed me to explore and express these complex emotions, which fueled this body of work.

Much of your work invites the viewer into a slowed, decelerated encounter with reading, sounding out syllables, tracing stitches, returning to fragments, piecing meaning together. In an era of accelerated visual consumption, what does it mean to ask for slowness? Is slowness, in your view, a political act, a sensory recalibration, or a gesture of care?

The gesture of asking the viewer to slow down stems from a repeated phrase I was told when I struggled to decode a word. As you can imagine, this statement has stayed with me for most of my life. Slowing down in an era of instant gratification is an interesting comparison. People today move through life quickly, often without truly living in the moment, consumed by their own self-interest. By creating a body of work that relies on the viewer’s patience and willingness to slow down, it keeps them present in the moment.

In a way, my work is a form of sensory recalibration, presented with a false sense of familiarity. The font, Times New Roman, creates that illusion because it is recognizable and associated with academic standardization. By using IPA to disrupt the viewer’s perception of reading, they are prompted to re-evaluate traditional reading. Asking for slowness invites the viewer to question not only the complexity of the English language but also to experience the struggle of reading my poems.

This is seen as a small act of political protest against standardization and rapid visual consumption. It questions the status quo, functioning as a political gesture, although a subtle one. On the surface, the protest is not obvious; it unfolds slowly as the viewer reads and interacts with the work, which is seen as an act of care and intentionality. Compared to artworks with more overt political messages that rely on shock value, my work reveals its quiet protest gradually, encouraging the viewer to remain present and engaged over time.

You often describe the page, the body, and the garment as porous zones in which language migrates. Where does a work begin for you, at the written word, the tactile material, or somewhere in between? Is there a point at which language stops being linguistic and becomes spatial, sculptural, or atmospheric? How do you navigate those thresholds without losing the emotional urgency of the text?

While I do not remember using that exact verbiage to describe my work, my pieces almost always begin with a poem, usually autobiographical and rooted in whatever emotional state I am working through, whether that involves dyslexia, healing, or experiences I have carried for years. I have been writing poems since I was a teenager, though I rarely shared them. For a long time, writing was simply a private way to process things. The first poems I ever allowed into the public sphere were the ones connected to dyslexia. Only this past year did I begin sharing poems about trauma, abuse, healing, and starting over. It felt uncomfortable at first, almost taboo, to place those emotions into the studio, but also freeing and unapologetic.

The poems carry the emotional energy that anchors the entire piece. Once the poem exists, the materials begin to form around it. That is where language begins to shift. When I translate a poem into color, scale, and IPA, it stops functioning strictly as text and becomes something else entirely. Even as it shifts into these other forms, I stay loyal to the emotional urgency of the poems by keeping the materials restrained and intentional, allowing the text to guide the experience.

There is a presence in my work that is similar to a sculpture. The poems give the works a weight, both emotional and physical. Seeing the work in person, rather than through a photograph, allows that weight to come through. The physical presence helps carry the emotion or, at times, the quiet intimidation embedded in the text.

I use color to help push the work toward a sculptural threshold. During my MFA, I explored how color and text can create a sense of objecthood. Our brains read words as images rather than as individual letters. Text is already an object. The way I present my work reinforces this idea. It allows the viewer to experience the poems not just as language, but as physical and visual forms.

In your process of layering, tearing, and rebuilding, one senses a desire not only to repair language but to expose its fractures. What is the emotional or ethical value of allowing the brokenness to remain visible? Do you find that vulnerability, linguistic, autobiographical, and perceptual, creates a more intimate encounter between the work and the viewer?

Being emotionally honest with the viewer, or with anyone, is one of the most freeing feelings a person can express. As unfortunate as it may be, showing a certain level of emotional vulnerability creates a sense of validation not only for the artist but also for the viewer. In one way or another, someone else has likely felt something similar or experienced something relatable. Hiding trauma or denying it does not bring anyone closer to healing or to reflecting and growing from the experience. Opening up, talking about it, or acknowledging it simulates the healing process. While everyone heals differently, the ability to have an open dialogue about trauma helps me heal and can benefit anyone who has experienced something similar.

This emotional vulnerability is what I maintain in my work. Embracing the brokenness and imperfections of human emotion is what gives the artwork its strength. It becomes tangible through the visible brokenness that mirrors the imperfections of human emotion.

Your series often operates like archives of the body’s encounter with language; they document stumbling, sounding out, mispronouncing, and rewriting. To what extent do you see your practice as autobiographical, and to what extent does it reach beyond the personal into a broader investigation of how language governs identity, permission, and authority? Do you think of yourself as rebuilding a private language or proposing a new public one?

My entire practice is rooted in my personal life. As stated in a previous question, all my IPA poems, both the dyslexia-related and the healing-related ones, refer to my lived experiences. Language, being the primary vehicle for conveying these emotions, allows for the reclamation of the constant battle of trying to understand and reshape its prescriptions. By presenting these poems in IPA, I also invite viewers to question who controls language and how its rules shape what is considered correct or legitimate, highlighting the ways language governs identity and access. In a way, the poems presented in IPA act as a private language while also asking the viewer to reconsider the idea of language itself.

In the studio, text becomes object, object becomes garment, garment becomes performance. This continual transformation suggests that meaning is never singular, but always in motion. When you look across your oeuvre, from sewn poems to affirmation cloaks and flags, what holds the pieces together? Is it the underlying belief that language is material, or is it something more elusive, a feeling, a rhythm, a pulse? How do you know when a work has found its final form, or does finality remain intentionally unstable?

The connection between all iterations of my work, from sewn pieces to poems, is the use of language as a material. My practice is centered on language and altering the way it is experienced. Each work begins with either a statement or a poem, which then guides the form to the final artwork. While the process involves transformation, turning text into an object, garment, or installation, each piece ultimately has a clear endpoint.

My approach blends thoughtful intentionality with intuitive expression. There are moments when, as I place letters on a canvas, an instinct or voice guides me to add or adjust something in the moment. Once the text is fully placed on the canvas or garment, I consider the work complete. The motion and evolution during the making, but the finished piece has a defined and intentional form.

Action Shot 1

Action Shot 2

Action Shot 3

Action Shot 4

Books

Boomerang

Shades of Gray

Studio view 1

Studio view 2

Studio view 3

Studio view 4

Studio view 5

Studio view 6

Studio view 7

Why Stay