Interview with Shimohara Aya

Solo Exhibition

2024 Feb. 「Mirror Mirror On The Post」 excube (Osaka/JPN)

2023 May 「AM I THERE ?」gallery GiGi (Kanagawa/JPN)

2020 Aug. 「hUMAn next」excube (Osaka/JPN)

2020 Mar. 「hUMAn」Garden City Space of Art (Taipei/TAIWAN)

2014 Jul. 「MOMENT」Ouchi Gallery (Blooklyn/USA)

Art Fair

2023 Nov. 「GINZA ART FESTA」Matsuya Ginza (medel gallery shu) (Tokyo/JPN)

2023 Mar. 「BAMA」BEXCO (Gallery edel) (Busan/KOREA)

2022 Nov. 「Diaf」EXCO (Gallery edel) (Daegu/KOREA)

2021 Oct. 「ART EXPO NY」Pier36 (Gallery edel) (NY/USA)

2018 Jul. 「ART FORMOSA」松山文創/Eslite Hotel (Taipei/TAIWAN)

2015 May. 「ART EXPO NY」Pier94 (KITAI Gallery) (NY/USA)

SELECTED Open call / Group / Curated

2026 Jul. 「TEXT-URE 2026」@CICA Museum(Ginpo/KOREA)

2025 Apr. 「All The Light I See」@Van Der Plas Gallery(NY/USA)

2024 Jun. 「ILLUSIONS」The Holy Art Gallery (London/UK)

2023 Nov. 「texture」TOKYO PARK GALLERY (London/UK)

2022 May. 「Exhibition of “SYNESTHESIA” vol.2」YOSEIDO Ginza FUTURE LABO (Tokyo/JPN)

2022 Feb. 「EPIC PAINTERS Vol.10 -PORTRAITS-」THE blank GALLERY (Tokyo/JPN)

2019 Nov. 「糸 ito」dear deer (Taipei/TAIWAN)

2019 Apr. 「THE STORIES」The Stories (DMOARTS) (Osaka/JPN)

2019 Apr. 「Vol.6 Aratapendan」Creative Center Osaka(Site of Namura Shipbuilding factory) (Osaka/JPN)

2017 Nov. 「UNKNOWN/ASIA2017」Herbis Hall (Osaka/JPN) *Prize

2016 Aug. 「LIFE」Noho M55 Gallery (NY/USA)

2015 Sep. 「JAPAN NOW」Espacio Gallery (London/UK)

2012 Nov. 「Seven deadly sins, seven virtues」ME & ART GALLERY (Sydney/AUSTRALIA)

Bibliography

2025 Apr. 「Al-Tiba 9 Contemporary Art Magazine #18」 (Spain)

2024 Oct. 「Create! Magazine #47」 Curated by Tax Collection and Square One Gallery (USA)

Public Art

2019 Mar. 「ART GUSH」Izumi city in Osaka/JPN *Installed on the tank tower of the Izumi Water and Sewerage Department.

Short Bio

She creates paintings on panels that imitate digital devices, with human nature as the main theme.

She started her career as a planner and designer in the apparel industry before becoming an independent artist in earnest in 2017.

Statement

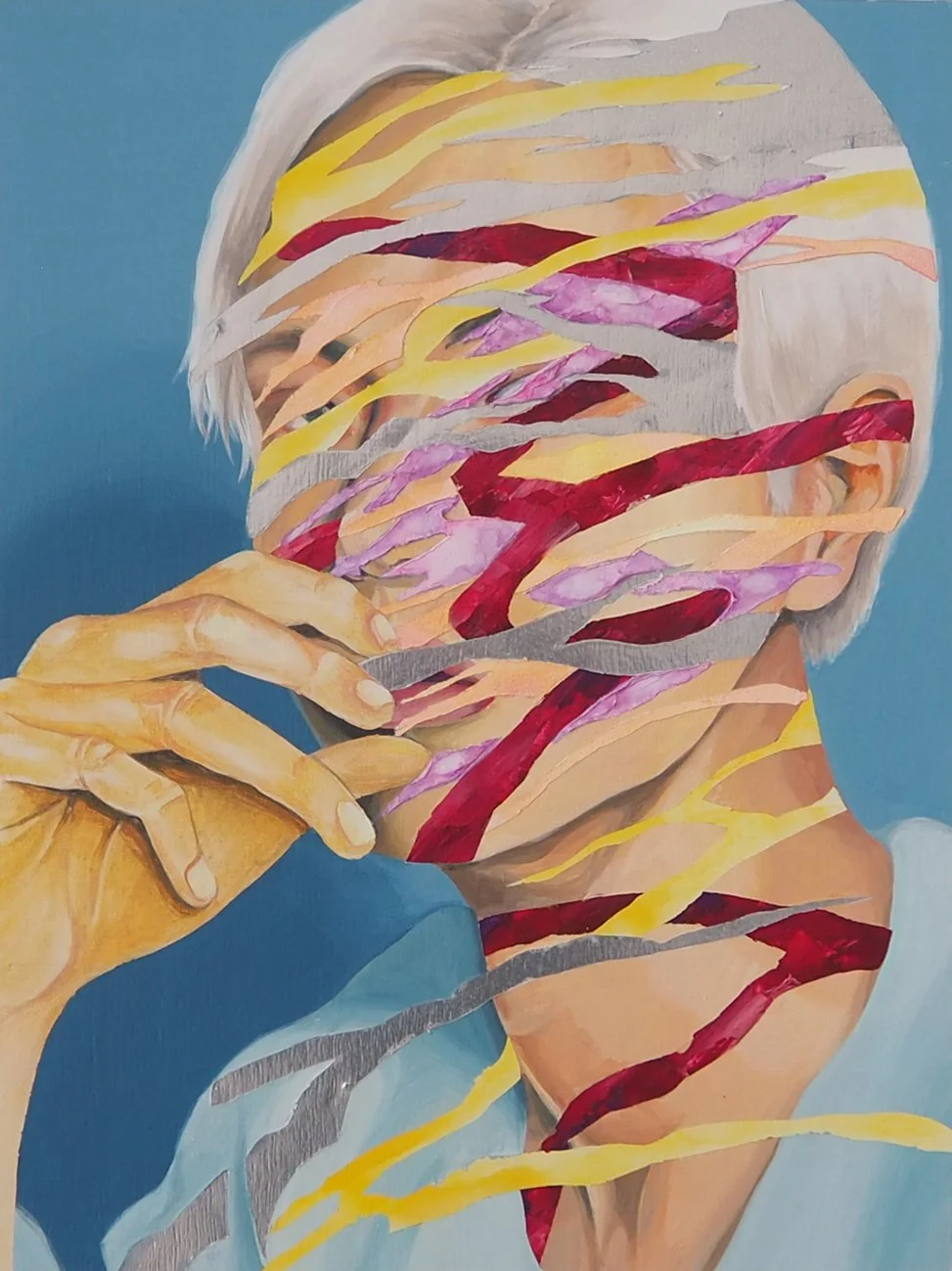

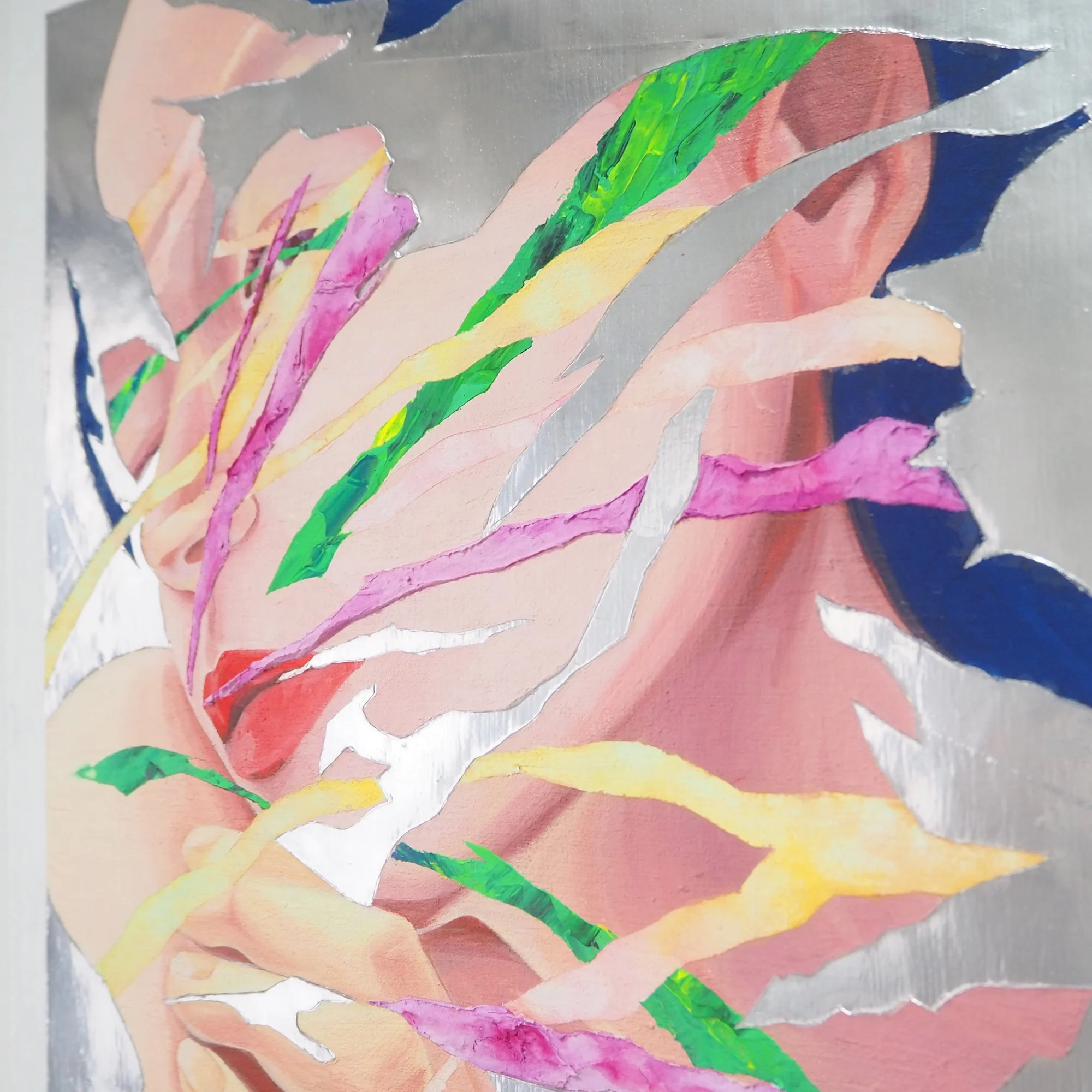

In creating my paintings, I use original wooden panels modeled after digital media aspect ratios like 16:9 and 4:3 as my support. This format references the screens of digital devices where modern people spend the most time, making us conscious of the very framework of the act of “seeing” that occupies so much of our daily lives.

On these screens, I paint motifs taken from selfies of strangers I encountered online. The images appearing on the screen are not completed in a single layer. Instead, they are constructed using various textures, layered upon one another, so that multiple layers coexist within a single picture plane.

Within one of these layers, I employ a unique technique using only paint to recreate a mirror surface, creating a device where the viewer themselves is reflected. This is not merely a technical challenge; it is a crucial element that allows the viewer to experience the central concept of the work.

There are two main themes I explore through my work. One is “ambivalence,” and the other is “the relationship between the self and others.”

First, I consider the concept of “ambivalence” to be a psychological trait unique to humans. Holding contradictory emotions simultaneously is a complex mental activity only possible for humans with highly developed frontal lobes, symbolizing the very essence of “humanity.”

I feel the act of taking selfies vividly embodies this ambivalent behavior. We desire to show ourselves and be acknowledged, yet simultaneously wish to maintain anonymity and secrecy. Sometimes we present an idealized version of ourselves through editing rather than showing our true selves; other times, we stage ourselves to appear like entirely different people.

Here, contradictions coexist: desire and anxiety, self-display and self-defense. It is precisely this complex movement of the human heart that strongly draws my interest, leading me to choose the selfie as my motif.

Selfies also serve as a crucial medium for exploring another theme: the relationship between others and the self. We often recognize our own emotions and positions through the presence and actions of others.

When we see someone else's selfie, we feel various emotions: envy, disgust, affection, interest, or even indifference. Tracing the essence of these feelings ultimately reveals what we ourselves felt and what values we hold, making others a catalyst for self-discovery.

In other words, others are mirrors reflecting ourselves; it is only through their existence that our own self takes shape.

I incorporate this metaphor of the “mirror” into my paintings as actual mirror surfaces, attempting to create a structure where viewers find themselves within the work.

This mirror surface is not merely metaphorical but possesses actual materiality. I applied mirror coating techniques used in industrial products to painting, developing a unique method to create a mirror surface using paint alone.

This was no easy feat, a technique reached only after numerous prototypes.

When a viewer stands before the painting, their own image is reflected within the canvas alongside the selfie of another. In that instant, the viewer is compelled not to passively “observe another,” but actively to experience “seeing oneself through another.”

This interactive mechanism is a defining feature of my work, a device that allows the viewer to directly experience the theme. Thus, my work engages with universal human psychological processes while referencing the visual culture of the digital age.

It prompts viewers to question their own contradictions, emotions, and the interrelationship between self and other through the image of another contained within the artificial frame of the canvas. This is precisely the endeavor I wish to realize through painting.

Aya, how do you think the decision to paint on panels that mimic digital screens invites a new kind of spectatorship, where the viewer is simultaneously confronted with the painted subject and their own reflected likeness, and how does this double vision complicate the distinction between looking at an image and being implicated inside it?

My decision to use panels that mimic digital screens originally came from a doubt about the conventions of painting formats themselves. Traditional canvases are defined by fixed systems—F, P, M sizes in painting, or A and B formats in print—that have been repeated for centuries. I began to question whether these inherited proportions still reflect how we actually see images today.

In everyday life, the media we encounter most frequently are no longer these historical formats, but screens—overwhelmingly shaped by 16:9 or 4:3 ratios. Starting from that observation, I chose to build my own panels, not as a stylistic gesture, but as a way to align painting with the visual conditions of contemporary life.

Consuming images, videos, and texts through screens is often perceived as a passive act—as if we could fully detach ourselves and observe everything as someone else’s story. When information is mediated by a screen, it can feel distant, objective, and separate from the self.

Yet I believe such detachment is an illusion. Even when we think we are simply consuming information, self-awareness is always involved. Our values, desires, insecurities, and emotions inevitably intervene in how we interpret what we see. We are never neutral viewers.

By transforming the screen into a physical painting panel and introducing a reflective surface, I make that invisible self-awareness visible. The reflection interrupts the illusion of distance and forces the viewer to recognize their own presence within the act of looking. What seems like observation from the outside is revealed as an experience that always includes the self.

When you speak about ambivalence as a central condition of your work, can you expand on how contradictory emotions are manifested materially in the layers of pigment, the shifting sheen of the mirrored surface, and the quiet melancholy that inhabits the figures you paint, where beauty, vulnerability, and voyeurism appear to coexist in the same field?

For me, ambivalence is not a sign of weakness or psychological conflict. On the contrary, I see it as one of the most advanced and fascinating qualities of being human. I became deeply interested in this theme around 2017, when AI began to develop rapidly. At that time, I started asking myself what truly distinguishes humans from other animals and from AI, and the answer that emerged was our ability to hold opposing emotions and intentions at the same time.

Compared to other animals, humans have a highly developed frontal lobe, which allows us to experience contradictory feelings simultaneously and even act in contradictory ways. At first glance, such behavior may appear inefficient or error-like, but I find in it a profound complexity, intelligence, and an almost tender quality unique to humanity. I believe that human richness and nuance reside precisely in the space that cannot be reduced to a simple yes or no. From this state of fluctuation emerge beauty, fragility, and melancholy.

In my paintings, ambivalence is embedded metaphorically in the layers and textures of the paint itself rather than depicted narratively. I use multiple media—primarily watercolor, acrylic paint, and mirror coating—within a single surface. To make these three materials coexist, different types of primer preparation are required; for example, watercolor does not adhere to standard acrylic gesso. This necessitates careful and layered preparation before painting even begins.

The differences between these materials ultimately enhance the sense of layering in the image. By allowing inherently incompatible media to coexist on a single support, the work physically embodies ambivalence—the simultaneous presence of disparate elements. At the same time, this structure alludes to the images we encounter on screens every day, which appear seamless but are in fact constructed through multiple layers of processing and editing.

Because the figures are painted from images originally meant to be seen, the act of looking inevitably carries an awareness of voyeurism—an awareness that heightens both attraction and discomfort.

The mirrored surface, however, does not symbolize ambivalence itself. Instead, it functions as a device that brings another key theme— the relationship between self and other—into the viewer’s direct experience. By reflecting the viewer’s own image, the work transforms from something that is merely observed into a situation in which the viewer becomes implicated.

The selfies you select are from strangers found online, yet they carry an intimate charge; what criteria guide your choice of faces, gestures, or poses, and how do you negotiate the ethical paradox between the anonymity of these individuals and the deeply personal resonance your paintings seem to evoke?

When I select selfies, my primary criterion is whether they convey a sense of ambivalence. I am drawn to images that contain contradiction—moments where opposing impulses coexist rather than resolve.

This sensitivity may be connected to my identity as a Japanese person. Rather than overt self-assertion, I am often more compelled by gestures of hesitation: modesty, calculated cuteness, or the subtle desire to be seen favorably. These are moments where the subject does not fully expose themselves, yet remains acutely aware of being watched. Within that restraint, I sense something deeply human. While I am sometimes drawn to the confident, self-assured tone of Western-style selfies, what most strongly holds my attention is a quieter tension.

Hand gestures play a particularly important role. To me, hands speak as clearly as faces. A peace sign or a hand placed near the chin reveals a psychological fluctuation between self-display and anonymity. At the same time, these gestures help structure the composition of the painting, tightening the visual balance while intensifying its emotional charge.

The intimacy and paradox that arise despite depicting strangers ultimately stem from my own position as a viewer. The moment I choose a selfie that resonates with ambivalence, subjectivity is already at work. By painting these images, I inevitably layer my own emotions and reflections onto them, making neutrality impossible.

I am not outside of these conditions; I am a human being shaped by the same human conditions I explore.

As a result, I do not treat these figures as personal portraits, but as fragments of a visual language shared within contemporary image culture. I maintain distance, yet remain emotionally involved. I see this paradox not as a problem to be resolved, but as the very essence of the work. The appearance of personal sensibility or fetishism is inevitable, and to me, it reflects the fundamentally human condition of seeing.

Your reflective surface developed through countless experiments with pigments, until it began to function as a mirror; how did this discovery alter your understanding of painting as a medium, and does the result feel closer to sculpture, interface, photography, or something that refuses categorisation altogether?

At an earlier stage of my practice, I used actual mirrors—plastic mirror sheets—cut and attached to the surface. While this approach functioned visually, it gradually began to feel uncomfortable to me. The work started to be described as mixed media, and that label didn’t fully align with how I understood my own practice.

It wasn’t that I was opposed to mixed media itself. If I had a strong conceptual reason to work in that category, it would have been fine. But personally, I have always felt that I am making paintings. Using a literal mirror felt like borrowing an essential part of the work from an external object, rather than resolving it within painting itself.

This discomfort became the motivation for my experiments. I began asking whether it was possible to create a reflective, mirror-like surface using only paint. If I could achieve that, I felt I could say with confidence, “this is a painting,” both to others and to myself.

Through many trials and failures, I eventually arrived at a method by adapting techniques originally developed for industrial mirror coatings. Even now, the process is not fixed—it continues to evolve through small adjustments and refinements.

Rather than shifting my understanding of painting toward another medium, this discovery reaffirmed it. The mirror-like surface is not meant to escape categorization, but to test how far painting can go. For me, the work remains firmly rooted in painting—not as a rigid category, but as an ongoing commitment to the medium.

The panels you build in 16:9 or 4:3 proportions echo the digital devices through which we see the world today; how has screen culture, with its endless circulation of self-images, shaped your aesthetics and your sense of contemporary identity, where the self appears simultaneously constructed and unstable?

I chose to work with 16:9 and 4:3 proportions because I feel that, for better or worse, the world we experience today is almost entirely mediated through screens. More and more, we come to believe that we understand places, events, and even people without physically being there—without using our senses—simply by seeing what is shared online.

At the same time, whatever we experience offline is eventually uploaded and absorbed back into the online world. There was a time when the internet felt like a second address, separate from physical reality. Now, those two realms feel fully merged. Our physical lives and our online activities no longer exist in parallel—they form a single, hybrid reality.

What appears on screens is always edited to some degree. We present ourselves more favorably, consciously or unconsciously guiding how others perceive us. This malleability holds both attraction and danger. Images become unstable, endlessly consumed, reinterpreted, and quickly replaced. I see this instability as one of the clearest characteristics of our time, and the screen as its most symbolic structure.

By translating these screen proportions into painting—into something slow, tactile, and materially present—I’m not trying to escape digital culture, but to hold it still. My work exists within this unstable reality, questioning what it means to look and to call something “real” in an age where the screen has become our primary lens on the world.

In your work, the viewer enters a non-reality that is nonetheless anchored in the everyday act of looking at screens; how do you envision the tension between fantasy and the ordinary, between escapism and the heaviness of the real, and do you consider this oscillation a form of emotional truth in itself?

Although my works may appear to depict a kind of non-reality, they are firmly grounded in one of the most ordinary acts of our time: looking at screens. The images I paint originate from everyday visual experiences—selfies, edited photographs, fleeting images that we encounter almost unconsciously. Because of this, the “fantasy” in my work is never completely detached from reality; it grows directly out of it.

I am interested in the tension between escapism and the weight of the real because I don’t think we ever fully move from one to the other. Screens offer us moments of escape, projection, and imagination, but they are also where anxiety, comparison, loneliness, and desire accumulate. What looks like lightness or play often carries a quiet heaviness underneath. In that sense, fantasy and the ordinary are not opposites in my work—they coexist and constantly bleed into each other.

I do consider this oscillation itself to be a form of emotional truth. Contemporary life rarely feels entirely tragic or entirely joyful. Most of the time, we exist somewhere in between—reasonably content, reasonably dissatisfied. That in-between state, where escape and reality overlap, feels closer to how emotions actually function today.

My work neither offers a clear escape route from reality nor confronts us with it head-on.

Many of your figures have an expression that is both vacant and intense, a suspended psychological atmosphere that recalls reverie, eroticism, and existential distance all at once; how conscious are you of this state, and what does the face become in a culture saturated with portraiture, yet hungry for genuine presence?

I think what we often long for—what could be called “true presence”—is, by nature, something abstract and undefined. When we try to present ourselves better, to refine or construct an image, there is often a quiet desire beneath it: the wish to someday become an ideal version of oneself. In Japanese, there is a common expression, “to want to become someone.” But who that “someone” is remains deeply vague.

Because this ideal presence has never truly been reached, it exists more as a yearning than a destination. I don’t see this as something negative. On the contrary, I believe it is a fundamental human condition. We remain suspended because the goal itself is unclear and perhaps unattainable. That suspension—between who we are and who we wish to be—is where humanity reveals itself.

This is why exposure and defense happen simultaneously. Satisfaction and dissatisfaction coexist. Melancholy emerges not from failure, but from continuing to desire something that cannot be fully defined or possessed.

In my work, the face becomes the site of this tension. It expresses emotion and identity, but also the ambiguity of never fully arriving at them. The faces I paint do not assert a stable self; instead, they linger in a state of becoming. That unresolved state—hovering between presence and absence—is what I feel most truthfully reflects contemporary emotional life.

You have spoken about finding a personal philosophy in Soseki Natsume’s “Three-Cornered World,” where art brings tranquility to life’s burdens; how does this literary foundation shape your responsibility as an artist today, and in what ways do you hope your paintings offer viewers solace, ambiguity, or emotional expansion?

I think it’s important to acknowledge that art has many different roles. Some works pursue beauty or technical excellence, others are deeply conceptual, while some aim to offer healing, joy, social critique, or new ways of seeing. I don’t believe there is a single correct function for art.

Natsume Sōseki’s The Three-Cornered World had a strong influence on how I think about art when I was an art student. What struck me most was its opening line, which says that art is precious because it softens the difficulty of living in the world. It’s a simple statement, but a powerful one.

At that time, there was a strong sense at the time that only conceptual art was considered “serious” or valid. Expressing personal emotions or private sensibilities in work was sometimes dismissed as self-indulgent or immature. Reading The Three-Cornered World at that time made me feel relieved. It suggested that art could exist in many forms, and that personal feeling was not something to be excluded.

I was also deeply moved by the novel’s ending. The painter protagonist looks at a woman he has feelings for and finds both beauty and sadness in her expression. From my perspective, as an artist he sees beauty, but as an individual he feels melancholy. That dual viewpoint—holding aesthetic distance while carrying personal emotion—felt extremely important to me.

Since then, I’ve come to believe that art doesn’t need to offer solutions or optimism to be meaningful. It doesn’t have to say “everything will be okay.” Art can soften the world simply by clarifying vague emotions—feelings we struggle to name, but recognize once they are reflected back to us.

As an artist today, I feel a responsibility not to dictate meaning, but to create space for viewers to encounter their own emotions honestly.

Gustav Klimt’s influence is visible in the luminous surfaces and ornamental shimmer of your paintings, yet the women you depict carry a darker essence of strength, grit, sadness, and emptiness; how do you balance these seductive formal elements with narrative undertones that suggest pain, vulnerability, and the fleeting nature of beauty?

Gustav Klimt’s influence on my work is often discussed in terms of surface—its luminosity, ornamentation, and sensuality—but what resonates most strongly for me is how his paintings hold opposing forces at once. Klimt frequently worked with clear contrasts such as eros and thanatos, youth and aging, desire and death. These tensions are bold and unmistakable.

However, I feel that contemporary life is shaped less by such dramatic oppositions and more by subtle, ambiguous emotional states. Most people today are neither purely happy nor deeply unhappy. They exist somewhere in between—reasonably content, yet quietly dissatisfied; stable, yet carrying an underlying melancholy. I believe this in-between condition is the reality of modern existence.

For this reason, the contrasts in my paintings are intentionally softened. Rather than staging explicit light and dark, strength and fragility, I aim to let these elements gently seep into one another. The figures I paint may appear composed, attractive, or confident, but small details—an uncertain gaze, a suspended gesture—suggest emotional instability or vulnerability beneath the surface.

I use seductive visual qualities as an entry point, much like Klimt did, but instead of dramatic symbolism, I focus on faint shifts in mood. I believe that even the smallest emotional nuances can carry great meaning. From quiet gestures and barely perceptible tensions, viewers can read longing, fatigue, desire, or loss.

In that sense, my work is not about illustrating contradiction, but about allowing ambiguity to breathe. I am interested in the kind of beauty that exists not in extremes, but in subtle fluctuations—where joy and sadness are inseparable, and where that very uncertainty feels deeply human.

In your exhibitions, viewers encounter images of strangers, and their own reflection within the same painted surface; do you think this produces a new understanding of empathy, where looking at others becomes a means of discovering oneself, and can this mirrored encounter challenge our assumptions about intimacy, identity, and the fragile boundaries between self and other?

I think the act of being physically reflected inside the painting functions as an effective device for experiencing the concept itself. I don’t believe there is anyone without self-consciousness. Even when we think we are simply observing others, our own awareness is always present. The mirrored surface makes that impossible to ignore.

Rather than offering a new understanding, I want the work to awaken parts of the psyche that we usually don’t bother to articulate or examine. Viewers may feel as though they are looking at someone else, but realize that they are, in fact, being exposed themselves. This mechanism reflects how we engage with images in everyday life—especially online.

For example, when scandals involving celebrities are harshly criticized on social media, people may believe they are expressing justice or moral judgment. But at the same time, what is really being revealed is the self: this is what I feel anger toward, this is the kind of opinion I hold. We think we are looking outward, yet we are constantly recognizing ourselves through others.

This realization can carry a quiet sense of loneliness. If everything ultimately originates from the self, that condition can feel isolating. It is not a dramatic or tragic loneliness, but a vague, everyday one—similar to being reasonably happy and reasonably unhappy at the same time. It is a feeling we rarely name, yet often live with.

The relationship between self and other, as I see it, is therefore slightly melancholic. But the ability to feel that melancholy—to sense ambiguity, contradiction, and emotional fluctuation—is precisely what makes us human. That wavering state, born from a highly developed capacity for thought, is the key point of my work. My paintings do not resolve this instability; they simply allow it to surface, quietly and honestly.