Interview with Monica Norum

Introduction

Monica Norum is a contemporary painter whose work explores painting as a site of presence, connection, and emotional resonance. Moving fluidly between abstraction and figuration, her paintings emerge through layered processes of intuition, revision, and material dialogue. Rather than illustrating fixed narratives, Norum creates open visual spaces where memory, vulnerability, and shared human experience can unfold. Her practice positions painting as both a perceptual and ethical act—one that invites slow looking, embodied attention, and relational engagement across cultural contexts.

Short Biography

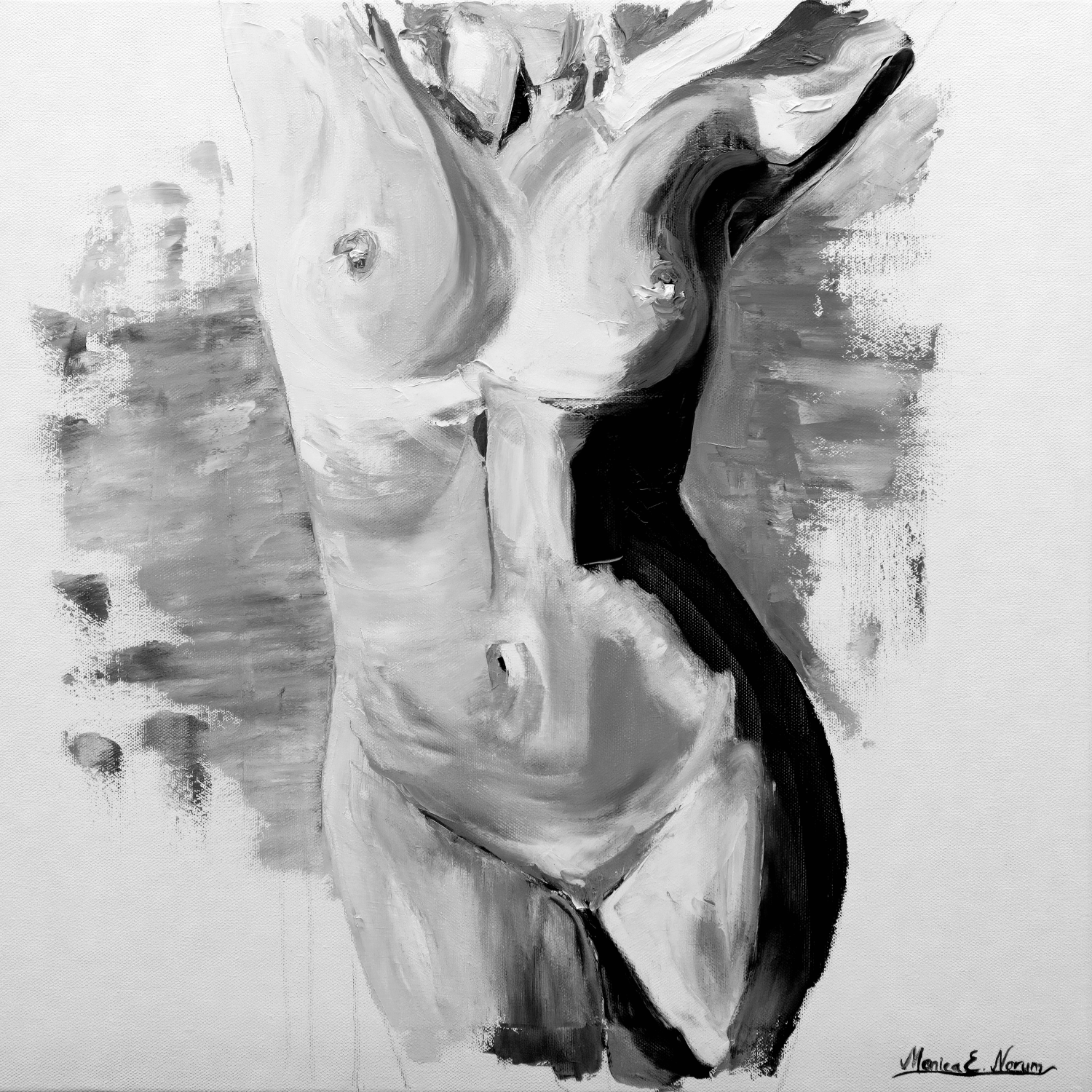

Monica Norum is a Norwegian artist working across oil, acrylic, and mixed media. She is known for her expressive paintings that balance structural awareness with intuitive gesture, often hovering between abstraction and figuration. Drawing inspiration from both the Old Masters—particularly the oil painting traditions of Rembrandt—and contemporary material practices, her work reflects a deep engagement with surface, time, and emotional presence.

Norum’s artistic journey began during a personally transformative period, where painting functioned as a means of grounding, regulation, and healing. This experience has since shaped her broader artistic mission: to create work that resonates beyond the personal and offers viewers a space for recognition, reflection, and connection. Her paintings have been exhibited internationally and are held in private collections, where they are valued not only as visual objects but as emotionally meaningful works.

Artist Statement

My practice is rooted in the belief that painting can function as a site of connection rather than assertion. I work intuitively, allowing images to emerge through layering, erosion, and revision. The process itself is central: meaning is not imposed, but discovered through sustained attention to material, color, and form. I am interested in what happens when the mind rests and the body, intuition, and emotion are allowed to lead.

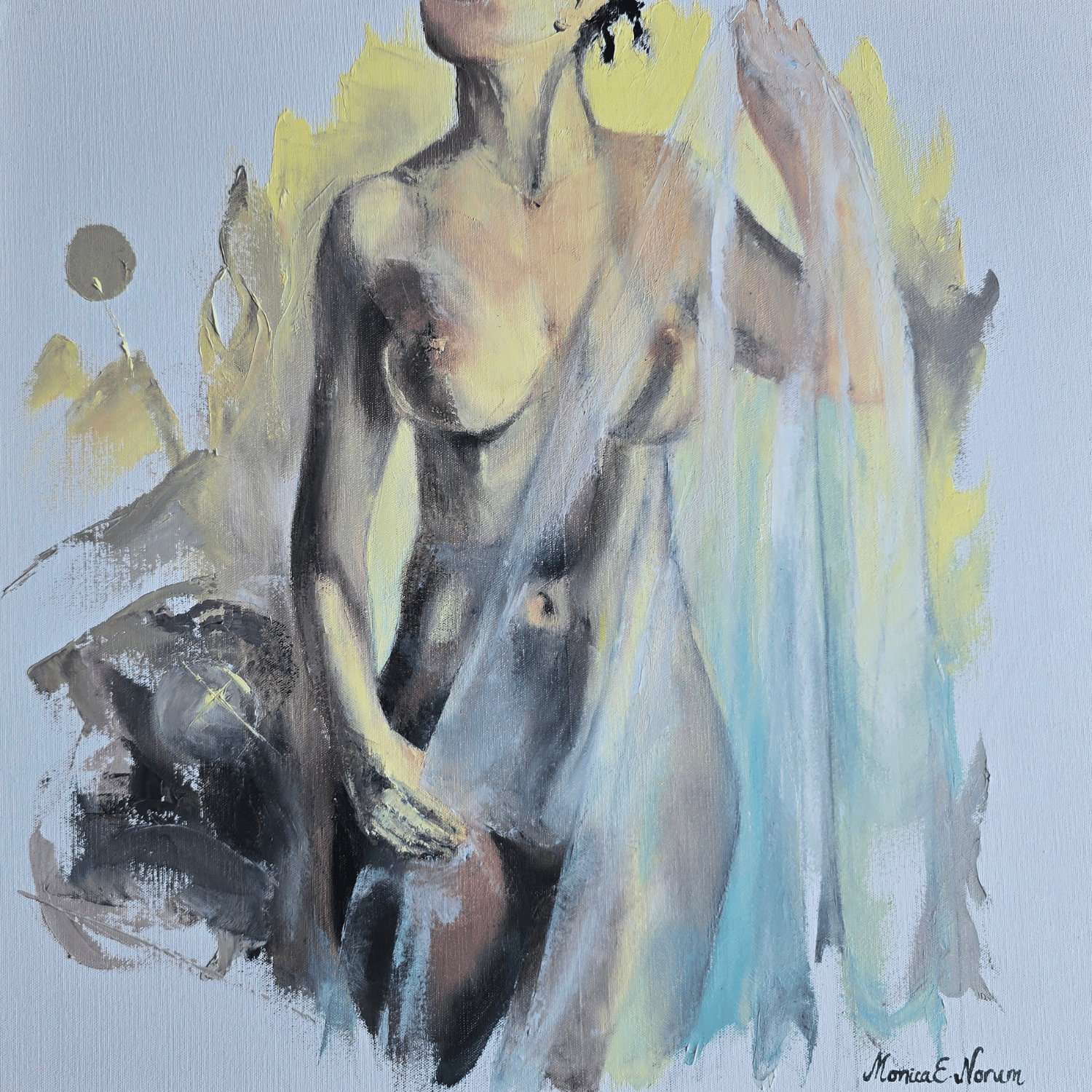

Much of my work exists in the space between abstraction and figuration. This threshold allows me to suggest presence—of a body, a face, or an emotional trace—without fixing it into a single narrative. By leaving elements unresolved, I invite viewers to enter the work with their own experiences. The paintings are meant to hold multiple emotional realities at once, allowing each encounter to remain personal and open.

My own experience of painting has been deeply healing, and this has shaped my artistic philosophy. I see art as a way of shifting focus—from pain to presence, from fragmentation to coherence. Research within art therapy supports what I have lived: that creative processes can support emotional regulation, resilience, and well-being. This understanding informs my ongoing mission to create work that not only engages visually, but offers a sense of care, recognition, and shared humanity.

Ultimately, my work is an invitation to slow down. In a world marked by speed and distraction, painting becomes a place where time thickens, perception deepens, and connection can quietly take place.

Monica, your paintings often show their own making through visible layers, revisions, and shifts in direction rather than a single resolved image. How do you think about painting as a way of thinking through experience, where working with material, change, and uncertainty becomes a method for understanding emotions, memory, and presence?

For me, painting is not about arriving at a fixed image, but about staying in dialogue with what unfolds. I think of the canvas as a place where experience is processed rather than illustrated. The visible layers, revisions, and shifts are traces of attention, hesitation, intuition, and listening. They mirror how we actually live and feel: through change, uncertainty, and constant adjustment.

Working with material allows me to think with my hands. Emotions and memories often exist before language, and painting gives them a physical form without forcing them into clarity too quickly. When I paint over something, scrape it back, or change direction, I am acknowledging that understanding is rarely linear. Presence, for me, comes from staying with what is unresolved and allowing it to transform rather than trying to control it.

In this sense, uncertainty is not something to overcome, but something to collaborate with. The process becomes a way of being present with my own inner landscape—accepting vulnerability, trusting intuition, and allowing meaning to emerge slowly through the act of making. The painting holds that history, and I believe viewers can feel it, not as a narrative, but as an emotional resonance.

Many of your works hover between abstraction and figuration, resisting fixed narrative while still suggesting corporeal presence, movement, or emotional trace. How do you negotiate this threshold, and what does this oscillation allow you to articulate about subjectivity, memory, or presence that a fully resolved image might foreclose?

I am drawn to the threshold between abstraction and figuration because it reflects how I experience subjectivity itself—as something fluid rather than fixed. I rarely begin with the intention of fully resolving a figure or dissolving it entirely. Instead, I allow the image to hover, to remain in a state of becoming. That oscillation creates space for ambiguity, and for me, ambiguity is where presence feels most alive.

By resisting a fixed narrative, the work can hold multiple emotional registers at once. The suggestion of a body, a gesture, or a face is enough to activate memory and recognition, but not enough to close meaning. In that in-between state, the painting can speak about memory as something unstable—fragmented, layered, and constantly rewritten—rather than something we simply retrieve.

A fully resolved image often answers too many questions. By staying at the edge between abstraction and figuration, I can articulate vulnerability, movement, and emotional trace without defining them. This allows the viewer’s own subjectivity to enter the work. Presence, then, is not located solely in the image, but in the encounter—where the painting remains open, and meaning continues to unfold through perception rather than explanation.

You have spoken about painting emerging during a personally transformative period, initially tied to bodily sensation and emotional regulation. How has this origin shaped your understanding of authorship over time, particularly as your work has entered institutional, commercial, and international contexts where personal experience becomes abstracted into a cultural object?

Painting began for me as a way to regulate the body and to stay present during a period of deep personal transformation. At that time, authorship was almost irrelevant; the act of painting was closer to a necessity than an artistic statement. It was about survival, grounding, and listening inward rather than producing an object for an external gaze.

Over time, as the work has moved into institutional, commercial, and international contexts, my understanding of authorship has shifted. I no longer see authorship as ownership of a personal narrative, but as responsibility for a process. The paintings still originate in lived experience, but that experience becomes translated—abstracted—into form, material, rhythm, and gesture. In that translation, the work detaches from my biography and enters a shared cultural space.

This distance has been important. It allows the work to function beyond me, without losing its emotional integrity. I think of the paintings less as expressions of self, and more as sites of encounter—where something that began as deeply personal can be met, reinterpreted, and reactivated by others. In this way, authorship becomes porous: rooted in my experience, yet completed through the viewer’s presence and the contexts in which the work circulates.

Your surfaces often reveal accumulation, erosion, and reworking, suggesting a temporal dimension embedded within the image itself. To what extent do you consider time as a structural element in your paintings, and how do duration, repetition, and revision function conceptually within your process?

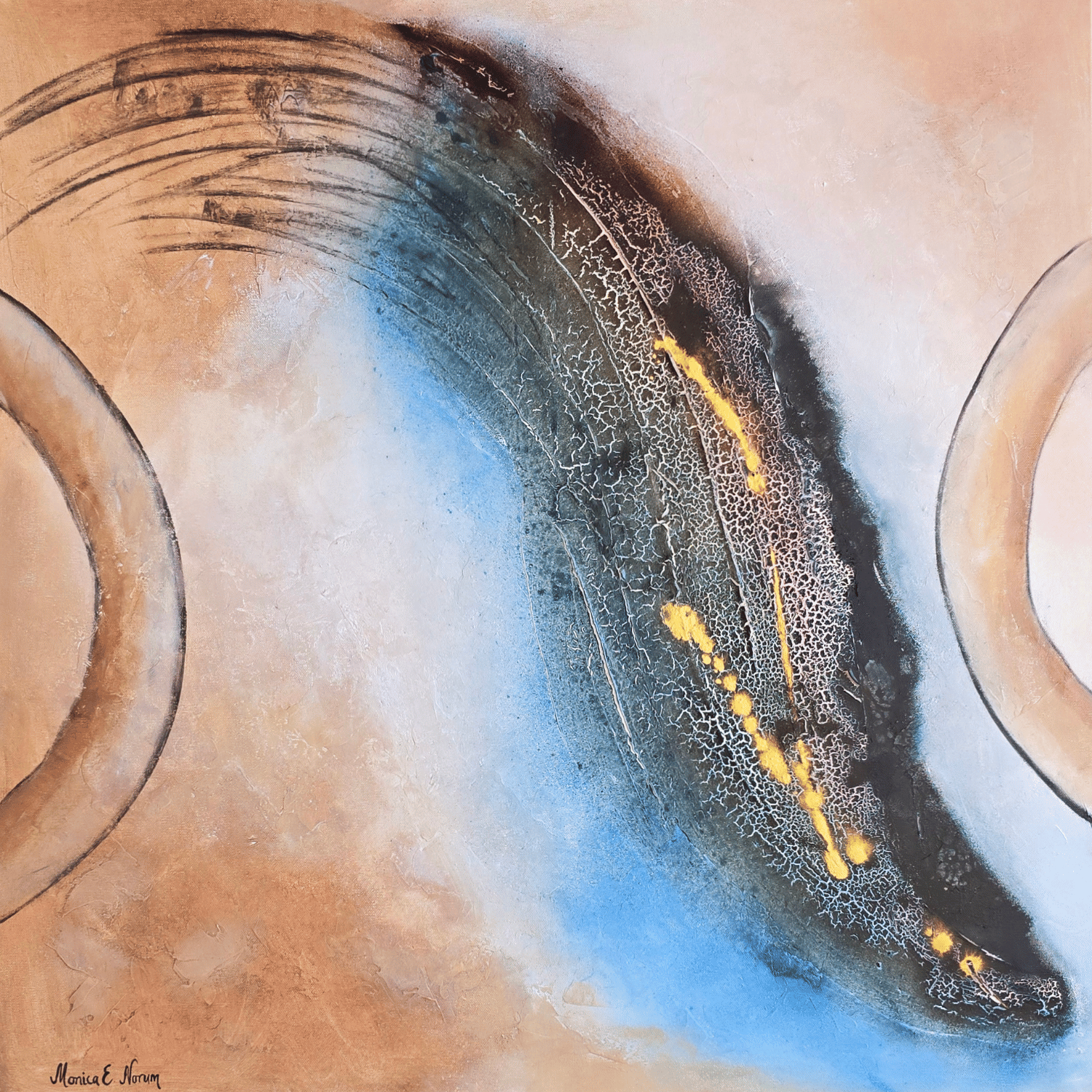

Time is not only present in my paintings as duration, but as an active force that shapes how the image comes into being. The abstract works are not planned in advance; they emerge through a process of layering, erasure, and response. Each layer of paint, texture, and color holds a moment of attention, and it is often only after many such moments that a focal point reveals itself. What becomes central in the image is rarely the result of intention, but of sustained engagement with the surface.

Play is essential in this process. By allowing myself to work intuitively with the ground—testing, disrupting, and rebuilding—I create conditions where something unexpected can surface. Time, in this sense, is embedded in the painting through accumulation and revision. The surface carries a memory of what has been there before, even when it is partially concealed. That history gives the image its depth and tension.

I work consciously toward a non-thinking state, where analytical decision-making gives way to presence. When the mind rests, the body and intuition take over. It is in this state that lines begin to appear—lines that speak to me. Sometimes they suggest the contour of a face, sometimes a symbolic form or a gesture charged with energy. These elements are not imposed on the painting; they are discovered through time spent listening to what the surface asks for.

Conceptually, repetition and revision function as acts of trust. Returning to the canvas again and again allows the work to unfold at its own pace. The final image is not a conclusion, but a moment of recognition—when something aligns, and the painting signals that it has found its own internal coherence. Time, then, is not something I move through in order to finish the work, but something I collaborate with, allowing the image to come forward through duration, attention, and letting go.

Color in your work appears both emotive and architectural, shaping spatial depth while simultaneously operating as a psychological register. How do you theorize your use of color in relation to perception, and do you see it as something that acts upon the viewer before interpretation or meaning?

Color is often the first point of contact in my work, acting directly on perception before interpretation or narrative begins. I experience color as something that operates on the body and emotions first, and I often think of colors as having the ability to “sing together.” Complementary relationships and monochromatic fields allow me to build resonance and tension, creating a psychological and spatial depth that is felt rather than explained.

Emotion functions as a barometer in my use of color. Certain palettes return repeatedly in my work because they carry a specific energetic and emotional weight for me. I am particularly drawn to jewel tones—deep blues, rich greens, and earthy hues—which often recur as grounding and stabilizing forces within the image. These colors allow me to work with both intensity and stillness, shaping an inner atmosphere that holds the painting together.

In my figurative work, especially when working with the human body or face, I allow myself to use the full color spectrum. However, the freedom of color is always held in balance with a strong awareness of value. For me, it is not the choice of color itself that determines whether a form reads as a body or a face, but the accuracy of the values. When the right values are placed in the right relationships, the figure becomes legible, regardless of hue.

Light and shadow are therefore essential structural elements. I work consciously with where light enters the image and how it shapes the form through shadow. This attention to value and light allows the form to emerge with clarity and vitality, giving the painted body or face a sense of presence and weight. Color, in this context, becomes both expressive and architectural—supporting emotional resonance while allowing the form to speak clearly.

Because of this, I do see color as acting upon the viewer before meaning. It establishes an immediate emotional and sensory orientation, while structure, value, and light sustain the image over time. Interpretation may follow, but it is grounded in an experience that begins at the level of perception and feeling rather than explanation.

Working across oil, acrylic, and mixed media, your practice resists medium purity in favor of hybridity. How do you situate this material plurality within a broader art historical context, particularly in relation to traditions that have privileged either expressive gesture or formal restraint?

My practice consciously moves between different art historical lineages rather than committing to a single notion of medium or style. When I work with portraiture and the nude, I use oil painting in direct dialogue with the traditions of the Old Masters. Artists such as Rembrandt remain important references for me, particularly in the way oil allows for depth, subtle transitions of value, and a profound sensitivity to light, flesh, and presence. In this context, oil is not a nostalgic choice, but a precise and time-tested tool for articulating the human body and psychological depth.

At the same time, my abstract work requires a different material language. Here, I often turn to acrylic and mixed media, which allow for greater density, immediacy, and physical force. These materials support a more expansive and expressive handling of the surface, enabling gestures, layering, and texture that would be more constrained within a traditional oil-only approach. I see this not as a break from history, but as an extension of it—aligning with modern and contemporary traditions that have expanded the role of material and process.

Historically, painting has often been framed through oppositions: expression versus restraint, tradition versus innovation, figuration versus abstraction. My practice resists these binaries. Different techniques serve different purposes, and one does not exclude the other. Moving between them allows me to remain attentive, challenged, and technically engaged. I would become limited if I confined myself solely to figurative oil painting, just as I would if I worked only abstractly with contemporary materials.

For me, hybridity is a way of maintaining artistic vitality. It allows for continuous refinement of technique while also leaving room for experimentation and risk. By working across materials and traditions, I situate my practice in a space where historical knowledge and contemporary expression inform each other—where mastery and exploration coexist rather than compete.

Your paintings frequently evoke states of connection, care, or inner intensity without illustrating them directly. How do you think about the ethical or cultural stakes of producing work that aims to uplift or inspire, especially within a contemporary art discourse that often privileges critique, rupture, or negation?

I am very aware that contemporary art discourse has often privileged critique through rupture, provocation, or negation. These strategies have played an important historical role in exposing power structures, violence, and exclusion. However, I do not believe that critique must always operate through shock or distance. There is also a critical potential in insisting on care, visibility, and emotional presence—especially in a world marked by fragmentation, war, and loss.

Rather than pressing the viewer down or confronting them with a fixed position, my work seeks to create a space where people feel seen and met. I believe that across cultures and nations, there is a shared human need for recognition and connection. Art, much like music, has the capacity to unite without erasing difference. Michael Jackson’s Heal the World articulated this beautifully, and that ethos resonates deeply with my own practice.

Several of my works have emerged directly in response to collective and personal crises. Total Peace was created as the war in Ukraine escalated. Black Rose was painted when the war first began. My Angel came into being shortly after my husband passed away on November 1st, 2025. These works are not illustrations of events, but emotional responses to moments where language felt insufficient. They carry grief, longing, fear, and hope simultaneously.

In this sense, my practice engages critically with contemporary conditions, but through resonance rather than confrontation. By allowing the work to remain partially unresolved, I leave space for the viewer’s own experiences to enter. The paintings are meant to hold multiple emotional truths at once, so that each person can encounter their own life situation—whether shaped by loss, love, conflict, or transition—within the work.

For me, the ethical stake lies in allowing art to hold complexity without prescribing meaning. The works are not meant to be merely beautiful objects, but companions—images that matter, that stay with the viewer, and that carry emotional weight over time. Choosing to work toward connection, care, and inner intensity is not a rejection of criticality, but an expansion of it. It proposes that presence, empathy, and openness can be just as radical as rupture in how art responds to the world we are living in.

As your work circulates internationally, how do questions of cultural translation and reception enter your thinking? Do you perceive your imagery as operating differently across contexts, and how do you reconcile a deeply personal visual language with its interpretation by diverse audiences?

As my work enters international circulation, questions of cultural translation and reception become less about difference in imagery and more about the conditions of encounter. I am conscious that every exhibition context carries its own cultural, historical, and institutional frameworks, and that these inevitably shape how the work is read. However, my practice does not rely on culturally specific narratives or iconography. Instead, it is grounded in affective states that precede language and ideology.

I work from the belief that fundamental human emotions—love, grief, joy, longing, fear—are shared across cultures and have been part of human experience since the beginning of time. While their expressions may vary socially or culturally, their emotional core remains recognizably human. By engaging with these shared emotional registers, the paintings operate on a level that allows them to move across borders without requiring translation in a literal sense.

From a curatorial perspective, the work can be situated within a transnational contemporary context that privileges affect, embodiment, and presence over narrative specificity. Color, gesture, spatial rhythm, and material accumulation function as carriers of meaning that are not bound to language or place. This allows the paintings to be read differently in different contexts, while still maintaining their emotional integrity.

The reconciliation between a deeply personal visual language and diverse interpretation lies precisely in this openness. The works originate in lived experience, but they are intentionally left unresolved. This indeterminacy allows viewers from different cultural backgrounds to project their own memories, histories, and emotional realities into the work. Meaning is not transmitted; it is activated.

In this way, the paintings do not assert a universal message, but they do appeal to a shared human condition. Their circulation across contexts becomes part of the work itself, extending its life beyond the studio and into a network of encounters where personal experience, collective memory, and cultural difference intersect. The work remains grounded in intimacy, yet capable of resonance on a global scale.

The tension between control and surrender is palpable in your compositions, where deliberate structure coexists with moments of apparent improvisation. How do you understand this dynamic in relation to artistic agency, and what does it reveal about your relationship to intuition, discipline, and risk?

The tension between control and surrender is central to how I understand artistic agency. I do not experience agency as absolute command over the image, but as an ongoing negotiation between intention and responsiveness. Structure provides a framework—through composition, value, rhythm, and spatial organization—but it is never meant to dominate the process. Within that framework, improvisation becomes a way of listening rather than asserting.

Intuition, for me, is not opposed to discipline. It is something that has been trained over time through repetition, technical refinement, and sustained attention. Years of working with form, color, and material have made it possible to trust intuitive decisions without abandoning rigor. What may appear improvised is often the result of deep familiarity with the medium and with my own perceptual habits.

Surrender enters the process when I allow the painting to resist my initial intentions. These moments carry risk, because they require letting go of control and accepting uncertainty. However, this is precisely where the work becomes most alive. Risk is not about recklessness, but about remaining open to transformation—to allowing the image to change me as much as I change it.

Conceptually, this dynamic reflects a broader understanding of agency as relational rather than authoritative. The painting is not something I impose meaning onto; it is something that emerges through exchange. Control and surrender are not opposing forces, but interdependent conditions that allow presence, intensity, and coherence to coexist within the work.

Several of your works suggest relational themes such as intimacy, interdependence, or shared presence without relying on explicit narrative cues. How do you approach the representation of relational experience in painting, and what formal strategies allow such themes to remain open rather than illustrative?

I approach relational experience in painting as something that is felt rather than narrated. Intimacy, interdependence, and shared presence are not experiences that lend themselves easily to illustration, and I am careful not to translate them into fixed scenes or recognizable stories. Instead, I work with formal conditions that allow relationality to emerge indirectly—through proximity, tension, rhythm, and resonance within the image.

One of the primary strategies is spatial ambiguity. Figures, forms, or gestures are often positioned in ways that suggest closeness or mutual influence without defining roles or identities. Edges remain porous, and boundaries between forms are allowed to blur, creating a sense of co-existence rather than separation. This ambiguity invites the viewer to sense relationship rather than decode it.

Color and value also play an important role. Shared tonal fields, mirrored hues, or subtle chromatic echoes create visual bonds between elements in the composition. These relationships are not symbolic but affective, allowing the painting to register connection through visual rhythm and balance. Similarly, repetition and variation across the surface can suggest dialogue or reciprocity without anchoring meaning to a single interpretation.

By resisting explicit narrative cues, the work remains open. Relational experience is not presented as a conclusion, but as a condition—one that the viewer enters rather than observes from a distance. In this way, the painting becomes a site of encounter, where relationality is not depicted, but activated through form, material, and perception.

Recognition through awards and institutional visibility often reframes how an artist’s work is read and valued. How has external validation influenced your self-perception as an artist, and how do you maintain conceptual autonomy amid the pressures of visibility and expectation?

External recognition has undoubtedly altered the context in which my work is received, but it has not fundamentally changed how I understand myself as an artist. Awards and institutional visibility can bring clarity and affirmation, especially in terms of how the work is situated within a broader cultural and professional field. They can open doors, create new conversations, and lend the work a certain legitimacy within established systems of value.

At the same time, I am careful not to let external validation become the measure of artistic direction. My practice was formed long before recognition entered the picture, rooted in necessity, process, and lived experience rather than expectation. That origin remains essential. I see recognition less as a confirmation of arrival, and more as a responsibility—to remain precise, honest, and attentive to the work itself.

Maintaining conceptual autonomy requires a continuous return to process. The studio remains a space where visibility and expectation fall away, and where decisions are guided by intuition, discipline, and material engagement rather than by reception or market logic. I try to hold recognition at a productive distance: acknowledging its impact without allowing it to dictate content or form.

In this sense, external validation reframes how the work is read, but it does not define its meaning. Autonomy, for me, lies in sustaining a practice that can withstand visibility without becoming shaped by it—one that remains responsive to inner necessity while operating confidently within public and institutional contexts.

Your paintings invite slow looking, asking viewers to engage with surface complexity and subtle transitions rather than immediate legibility. How do you position the viewer within your work, and what kind of perceptual or cognitive labor do you hope the paintings solicit?

I think of the viewer not as a passive recipient, but as an active participant in the work. The paintings are constructed in a way that resists immediate legibility, precisely to slow down perception and invite sustained attention. Surface complexity, layering, and subtle transitions are not meant to be decoded quickly, but to be entered gradually.

By asking for slow looking, the work proposes a different rhythm than the one we are often conditioned to in contemporary visual culture. It encourages the viewer to stay with uncertainty, to notice small shifts in color, value, texture, and form, and to allow meaning to emerge through duration rather than instant recognition.

The perceptual labor I hope the paintings solicit is not analytical in a strict sense, but attentional. It is about being present—allowing the eyes and the body to move through the image, to sense depth, resistance, and resonance. Cognitively, this involves suspending the need for immediate interpretation and instead engaging with the work as an unfolding experience.

In positioning the viewer this way, the painting becomes a site of mutual presence. Meaning is not delivered; it is co-created. The viewer’s time, memory, and emotional sensitivity complete the work. Slow looking, then, is not a demand, but an invitation—to enter a space where perception is allowed to deepen, and where attention itself becomes a form of care.

In an era marked by digital saturation and accelerated image consumption, how do you conceive of painting as a contemporary medium? What forms of resistance or continuity does your practice propose in relation to speed, immateriality, and distraction?

In a time defined by digital saturation and accelerated image consumption, I experience painting as a medium of resistance through slowness, materiality, and presence. Painting insists on duration—both in the making and in the viewing—and it cannot be fully absorbed through a screen or in passing. Its physicality asks for proximity, time, and embodied attention.

My practice proposes continuity with a long history of painting while simultaneously addressing contemporary conditions. The accumulation of layers, revisions, and surface complexity stands in contrast to the instant clarity and disposability of digital images. Where digital culture favors speed and immateriality, painting reasserts weight, texture, and resistance. It requires friction—between hand and surface, intention and uncertainty.

At the same time, I do not see painting as nostalgic or oppositional in a simplistic sense. Its relevance lies precisely in its capacity to hold complexity over time. The paintings do not compete with digital images on the level of immediacy; instead, they offer an alternative mode of engagement—one that values sustained attention, sensory depth, and perceptual openness.

In relation to distraction, my work does not attempt to overpower or shock the viewer into attention. Rather, it creates a space where attention can return naturally, through slow looking and subtle shifts. Painting becomes a site where the body and the gaze are invited to settle, even briefly, outside the accelerated rhythms of contemporary life.

In this way, my practice understands painting as both a continuation of a historical medium and a contemporary proposition: a form that resists dematerialization by insisting on presence, and that counters speed not through refusal, but through depth.

Looking across your body of work, there is a persistent inquiry into how painting can function as a site of connection rather than assertion. How do you envision the future trajectory of your practice in terms of its philosophical commitments, and what questions feel most urgent for you to pursue now?

Looking across my body of work, the persistent inquiry into how painting can function as a site of connection rather than assertion is deeply bound up with what I have come to understand as the healing potential of art itself. My personal experience with making art has been profoundly restorative; painting has helped me move through difficult emotional landscapes and find presence in moments of loss, anxiety, and transition. This lived experience has shaped my belief that creative engagement can offer a powerful path toward shifting focus from something painful toward something generative.

This belief resonates with clinical and psychological research on art therapy—a discipline that uses creative processes like painting and drawing within a therapeutic context to support emotional expression, psychological resilience, and well-being. Art therapy has been shown to help people express themselves more freely, improve emotional health, and enhance interpersonal relationships, particularly in conditions such as anxiety, depression, and trauma where verbal expression alone may be limited.

Studies also indicate that art-making can reduce distress, improve mood, and enhance quality of life when compared with control groups who did not engage in artistic processes. In clinical settings, art therapy is increasingly recognized as a complementary treatment that may ease symptoms of mental health conditions and facilitate emotional processing in ways that traditional therapies sometimes cannot.

For me, this research underscores what I have seen in my own practice—and what I hope others experience through engagement with art. Painting does more than represent an idea: it invites presence, slows perception, and opens space for reflection. It allows individuals to access and articulate complex feelings in ways that bypass the limitations of language. In this way, art becomes a shared language of the human condition—one that can speak to love, grief, joy, and resilience across cultures and contexts.

Philosophically, I see my future practice continuing to explore these questions: how can painting hold emotional complexity without prescribing a single reading? How can creative experience support emotional regulation, presence, and connection in a world that often prioritizes speed and distraction? These inquiries remain urgent because they speak not only to artistic concerns, but to the fundamental human need for meaning, empathy, and shared presence.

Ultimately, my mission is not only to make work that resonates aesthetically, but to invite others into a creative experience that feels life-affirming and accessible—especially for those navigating struggle. I want people to feel seen by the work, to find their own stories and emotions reflected, and to discover that through engagement with art there can be a pathway toward connection, understanding, and well-being.