Mary Di Iorio

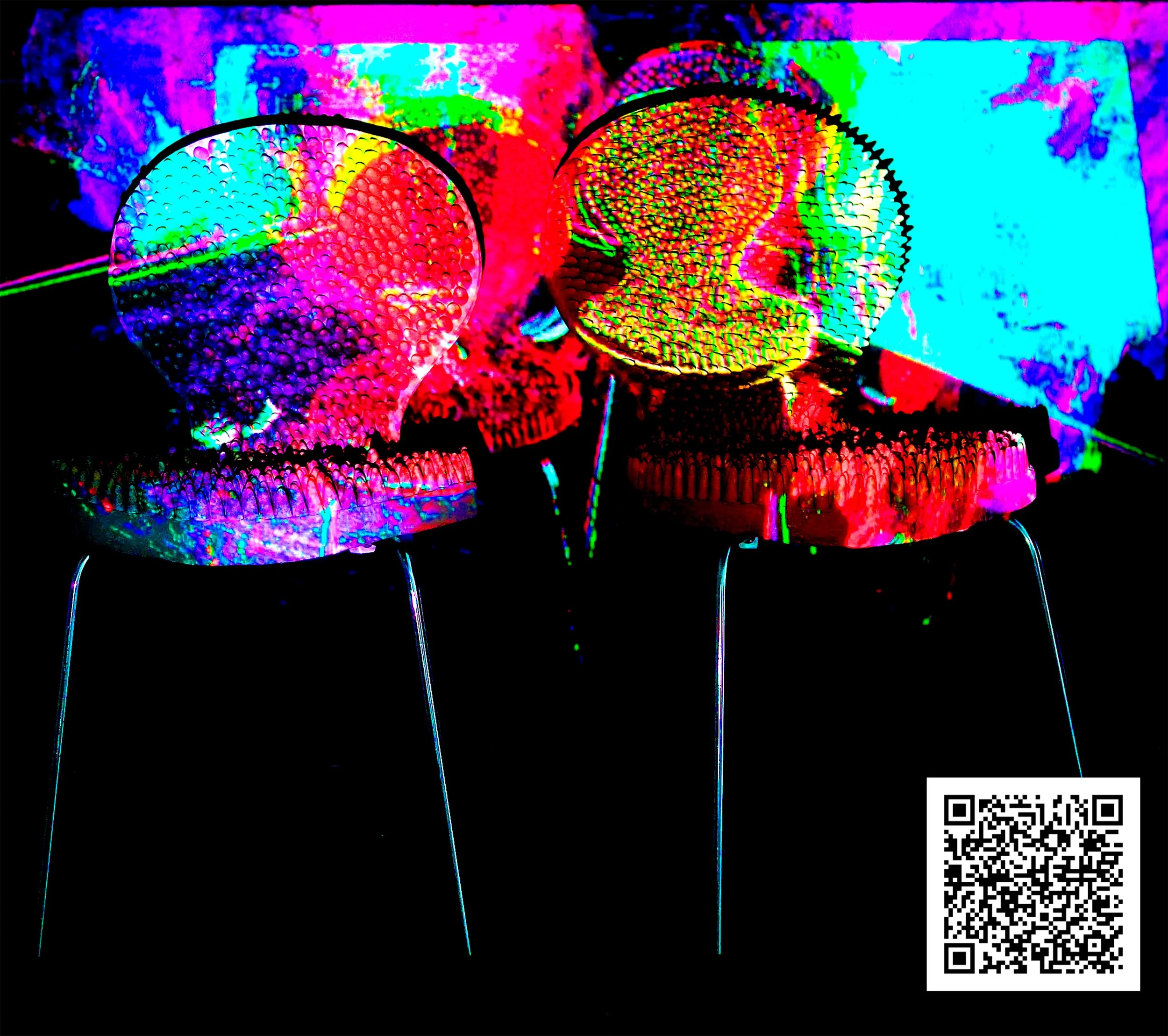

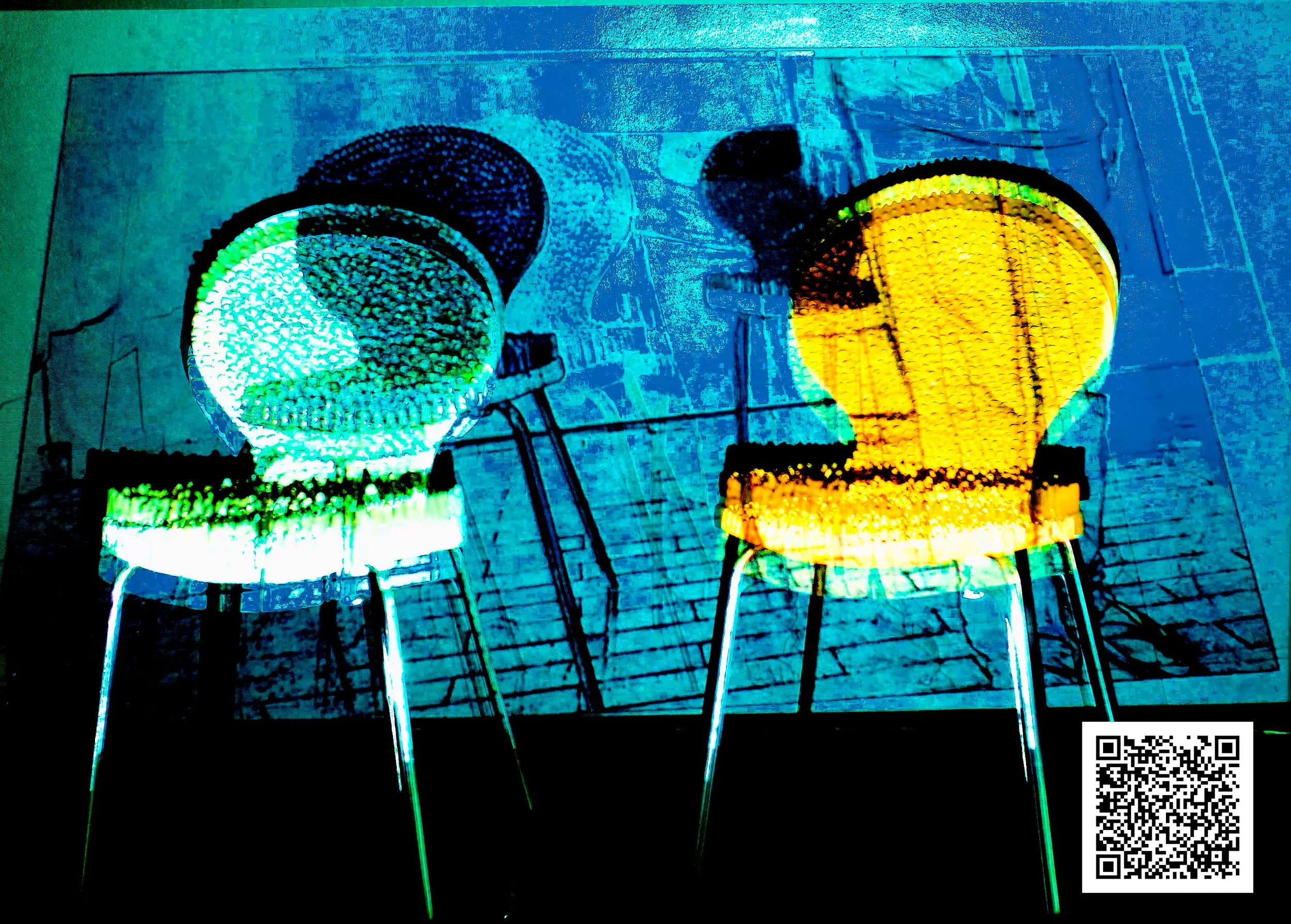

Mary Di Iorio’s recent cycle, Cathedra, unfolds as a lucid meditation on material thought, clay thinking itself through motion, vibration, and the recursive time of the loop. What might once have been called a “medium” in the classical sense, ceramic, with its kiln-fixed ontology and its history of use, appears here not as a stable category but as a field traversed by vectors: filmic duration, acoustic insistence, the hand’s labor, the screen’s glow. To watch these short moving images is to enter a regime in which form is not given but perpetually negotiated, where the ceramic object refuses its customary submission to gravity, utility, and silence, and instead insists on becoming, becoming animated, becoming audible, becoming an idea.

Di Iorio names her project a re-signification of ceramics, and that phrase is exact. It is not the decorative supplement of animation pasted onto the object; it is a reconfiguration of sign-relations in which clay, indexed to earth, to heat, to weight, becomes a sign that can move across codes. The “anima” she invokes is not the old metaphysical breath but a structural condition: the animation that contemporaneity performs on the so-called “fixed” arts, a post-medium logic in which matter is read and reread through technological apparatus, and apparatus is tempered and humanized by matter. In Cathedra, the ceramic form is filmed, cut, looped, and sounded; its porosity and sheen become the ground of a choreography in which the eye learns to listen and the ear learns to see.

The choice of title, Cathedra, is both witty and pointed. A cathedra is a seat of teaching, a chair of authority; in ecclesiastical architecture, it is the stone locus of a voice. Di Iorio, a visual artist, researcher, and professor specializing in the history of art and architecture in Brazil, has long inhabited such a place of speaking. But this cathedra is clay, not stone; animated, not inert; polyphonic, not unitary. In these works, the chair of authority becomes a site of unlearning and re-voicing, where the doctrinal fixities of medium and function are loosened, even joyfully contradicted. The result is a kind of pedagogical poetics: the work teaches us how to perceive again.

Across the videos, one senses the sedimentation of decades, of making, reflecting, teaching, and exhibiting. Di Iorio’s career traces a topology of Brazilian art institutions and international platforms, from early solo exhibitions in Belo Horizonte and across major Brazilian museums, the National Museum of Fine Arts in Rio de Janeiro, MASP in São Paulo, the Museums of Modern Art in Rio and Bahia, and the Museum of Art of Rio Grande do Sul, to more recent appearances in the accelerated circuits of global visibility: ArtExpo New York (April 2025), ARTEOM Gallery (May 2025), and ARTBOXY LIVE during Art Basel Week in June 2025, alongside presentations in Berlin, Dubai, and Zurich. The trajectory is instructive. It reveals an artist who has moved steadily from the modernist institutional matrix into today’s networked system of screens and fairs, while maintaining a rigorous criticality about what it means to make form in time.

The Cathedra videos are short, looped, and insistent. The loop, as a structural device, does several things at once. It brackets narrative and denies the teleology of “before and after” that traditional ceramics embodies: wet clay, throwing, drying, firing, glaze, vitrification, the final, finished thing. Instead, the loop returns the object to a condition of ongoingness. In Kraussian terms, the loop presses us into the expanded field of sculpture, where the object is not sculptural because it occupies a discrete volume but because it articulates relations: between image and thing, duration and touch, sound and surface. Di Iorio asks for the sound to be loud, “it is the sound that definitively confirms their movements,” she notes, and this insistence is crucial. The acoustic track anchors the ceramic’s apparent motion, refusing the purely retinal and reminding us that our perception is a synesthetic instrument. The sound does not describe the clay; it compels it, making audible the frictions, contacts, and rubs that are the true subject of the work.

There is, too, a philosophical clarity to the project’s declared aim of deconstructing form and function. Ceramic history is shadowed by utility, plate, cup, jar, and by the modernist redemption of that utility through “pure form.” Di Iorio refuses both. She does not return to usefulness, nor does she sanctify autonomy. Instead, she moves laterally, inventing a third term in which the forms are re-proposed: not functional but propositional. The works are propositions for how an object might behave if liberated from the kiln’s finality and from the museum’s hush. What we encounter are procedures of observing, constructing, and reconstructing that frame the ceramic as an event. The “first function,” as she writes, is nullified not in a destructive gesture but in a generative one; the object is invited to serve a different economy of attention, a new ecology of sense.

To situate Di Iorio within a lineage is to recognize how deftly she speaks to Brazilian modernism’s profound rethinking of participation and perception. It is not a far reach to hear an echo of Lygia Clark, not in material resemblance but in the ambition to reprogram the sensorium. Clark’s “propositions” turned the spectator into a participant; Di Iorio’s loops turn the spectator into a listener-witness, attentive not to narrative resolution but to processual becoming. There is also an affinity with Hélio Oiticica’s insistence that color and structure are events in space rather than inert properties; in Cathedra, surface and sound are likewise events, always arriving. Yet another reference might be Lucio Fontana, whose Spatialism cut the canvas to expose a beyond; Di Iorio does not slash but animates, opening the ceramic’s surface to time and its volume to vibration. If Fontana sought to puncture matter to let space in, Di Iorio vibrates matter to let time out.

The historical intelligence of the work owes much to Di Iorio’s dual role as artist and scholar. As a founder of the Faculty of Arts at the Federal University of Uberlândia in 1972, serving as professor and department head, she helped shape a generation’s understanding of art’s discursive and practical infrastructures. Her subsequent study at the Accademia di Belle Arti “Pietro Vannucci” in Italy, where she documented her experience as a ceramics instructor, broadened her lexicon at a crucial historical juncture. The bibliographic commitment runs parallel to the studio practice: her publications, from Arte Cerâmica no Ensino (1981/1984) through MARY DI IORIO (1991, with a preface by Pietro Maria Bardi) to Cerâmica no Brasil: Sistematização Bibliográfica (2014), testify to a mind that treats making and thinking as interdependent crafts. This braided competency, hands that read, eyes that touch, animates Cathedra at every turn.

One of the series’ most striking achievements is the way it treats technology not as glamour but as grammar. Di Iorio is candid about the pressures of technological acceleration; the internet has long been embedded in her process, and in Cathedra, it becomes not merely a distribution channel but a constitutive frame. The works are designed for online visibility, “without prediction,” as she puts it, yet they refuse the flattening that so often afflicts screen-based art. Because the source is clay, with its minute textures and stubborn volumes, the digitized image carries an analogue density that resists dematerialization. The friction between the haptic and the pixellated is productive, yielding a third texture that belongs to neither alone. Here, the loop is again decisive: by insisting on return, the works resist the scroll’s forward drag; they ask for dwelling.

If we attend to the compositional strategies, we encounter a language of modular fragments, recombined and permuted. The ceramic units, folds, lips, ridges, and concavities meet the editing suite’s cut, dissolve, and speed shift. The result is an articulate stutter: a rhythm of approach and withdrawal, emergence and eclipse. This grammar is not mere style; it is ontological. The ceramic, relieved of its fixed function, becomes speech. And because it is speech, it is addressed to someone, us, and it requires our reply, which here takes the form of attentive looking and listening, the patience to experience micro-change.

Di Iorio’s sense of scale is likewise significant. These are not monumental videos; they do not perform scale as spectacle. Rather, they work at the scale of intimacy, close-up yet never fetishistic, proximate yet not possessive. In Krauss’s terms, they occupy the “indexical” register: the camera documents the trace of a hand and the stubbornness of a surface. But because the image is constructed and looped, the index is neither naïve nor transparent. It acknowledges its own artifice, and in so doing it frees the viewer from the false choice between authenticity and construction. Cathedra proposes a third term: authentic construction, the truth of a process that is both embodied and mediated.

Within the contemporary scene, diffuse, hybrid, platformed, Di Iorio’s work occupies a distinctive position. At a moment when much digital art emphasizes novelty of tool over necessity of form, Cathedra is bracingly necessary: it takes technology as a challenge to the ethics of perception rather than as an end in itself. The societal importance of such a stance cannot be overstated. We live, as she notes, amid rapid technological shifts that demand new modes of living and working. The temptation is to accept acceleration as destiny. Di Iorio offers an alternative: an ethics of slowness inside the loop, a pedagogy of attention in which a fired object, historically the emblem of the irreversible, becomes reversible in time, not by undoing but by recoding. This is not nostalgia for materiality; it is a forward-facing care for how material and media can co-compose the human sensorium.

Her tone is not apocalyptic but playful, “creation and audacity,” she writes; intersections, contacts, friction. The seriousness of the project resides precisely in this play, which breaks the aura of permanence around ceramics without discarding its dignity. The works become sites of contact between tradition and experiment, craft and code, sound and sight, Brazil and elsewhere. That the series has traveled through international venues in 2025, New York, Basel, Berlin, Dubai, Zurich, while echoing the deep institutional memory of Brazilian museums, is not a contradiction but a coherence: Cathedra is both local and connective, grounded and transmissible.

To compare Di Iorio to a single figure from the past is finally reductive, but if we must choose, Lygia Clark provides the most meaningful counterpoint: both artists are engaged in the production of sensory propositions that unfix the artwork’s function and demand a different subject. Where Clark turned the spectator into a tactile actor, Di Iorio turns the viewer into an attentive auditor of surfaces, a reader of rhythms. The difference is the time of the screen, the loop, through which Di Iorio composes a new contract between viewer and work: repeat, listen, perceive again. That compact yields not passivity but agency; the viewer’s responsibility is not to consume but to attend.

It is important to mark, too, the sheer craft underlying the conceptual intelligence. The ceramic forms possess a measured elegance: edges that catch light, cavities that chamber sound, glazes that modulate reflectivity. The camera is not an afterthought; it is an instrument tuned to the objects’ minute dramas. Editing is exact but never mannered; sound is assertive without coercion. The totality is a construction of sense, not an overlay of effects. This is why the works can endure the demand Di Iorio makes of them: loudness, looping, the rigors of online display. They are not exhausted by repetition; they produce it.

In the broader ecology of contemporary art, Cathedra answers a need we often fail to name: a need for works that teach, not in the didactic mode, but through structures that cultivate attentiveness. Di Iorio’s long history as a professor and researcher inflects the series without ever moralizing it. The cathedra becomes a laboratory, the chair of authority converted into a stool of experimentation. That conversion is profoundly democratic. It suggests that authority today resides not in pronouncement but in process, not in the first function but in the courage to nullify and re-propose.

To praise Mary Di Iorio is to recognize how rare it is to encounter an artist who can change the terms of a medium without abandoning its body. She is, in the best sense, a maker of problems: each work poses a question to perception, to habit, to history. And each returns, in the loop’s generous way, to ask again, never quite the same. In an art world so often seduced by novelty’s glare, Di Iorio offers originality as rigor: an originality born of decades of inquiry, of books written and classes taught, of museums and studios and the daily craft of thinking with one’s hands. She animates clay, and in doing so, animates the very idea of what art can be now.

Cathedra is not a destination but a passage: a series that will continue to branch as sound finds new frequencies, as forms fold differently, as viewers learn to listen with their eyes. It is a body of work that sits, like its title, at a paradoxical threshold: both seat and launchpad, both tradition and transgression. From Belo Horizonte to Basel, from the kiln to the codec, Mary Di Iorio has built a practice committed to resignification as a form of care for materials, for audiences, for the future of art. In her hands, ceramics, animated, sonorous, iterable, become a contemporary cathedra: a place from which the work speaks, and from which we, if we are attentive, may learn to listen anew.

By Marta Puig

Editor Contemporary Art Curator Magazine

114-Cathedra-05-05- ANO 2025

111-Cathedra-04-06 - ANO 2023

120-Cathedra-01-05 - ANO - 2025

116-Cathedra-03-03 - ANO - 2025

115-Cathedra-03-06- ANO- 2025

115-Cathedra-02-06- ANO - 2025

117-Cathedra-03-04-ANO-2025

102-Cathedra-05-05-ANO-2023

107-Cathedra-06-06-2023

108-Cathedra_001_03-ANO-2023