Hans van Wingerden

In an era increasingly saturated with visual noise, an age in which the image has become its own form of entropy, Hans van Wingerden’s art insists on the persistence of meaning. His works are not simply aesthetic objects; they are cognitive devices, visual arguments about the state of perception itself. For nearly five decades, van Wingerden has traversed the dense terrain between materiality and concept, from his early photorealist explorations of the 1970s to the luminous, multi-layered neon constructions that define his mature oeuvre. In this trajectory, one perceives not a restless experimentation but a sustained philosophical inquiry, an attempt to reconstitute the integrity of the image in a world that has rendered it banal.

Born in the Netherlands and educated at the Academie for Art and Design in s-Hertogenbosch (1969–1974), van Wingerden emerged during the twilight of modernism and the ascendance of postmodern doubt. Awarded the prestigious Koninklijke Subsidie (Royal Grant) in 1977, he initially aligned himself with the technical precision of photorealism. Yet, as he later reflected, the medium’s laborious fidelity to surface detail felt inadequate for his deeper artistic inquiry. The photograph’s dominance, the mechanical reproduction that Walter Benjamin called “the withering of the aura,” forced van Wingerden to ask what art could still mean in a world of ceaseless replication. His journey from realism to conceptualism was thus not a stylistic mutation but a philosophical necessity.

By the mid-1990s, after years of formal research through figuration and abstraction, van Wingerden’s work achieved a decisive synthesis. Binnenwereld:Buitenwereld (1996), a diptych oil on canvas, marks a turning point. The title, Inner World: Outer World, declares the dialectic that would come to dominate his later oeuvre. The painting retains vestiges of the material surface, its brushstrokes charged with energy, yet the division of the image into two panels already signals a move toward conceptual duality. The division is not merely compositional; it is epistemological. Here van Wingerden establishes a visual metaphor for the split condition of contemporary subjectivity, the fractured consciousness of a being suspended between interior reflection and external illusion.

Rosalind E. Krauss once wrote that modern art operates within an “expanded field” in which medium specificity collapses and new structures of meaning emerge. Van Wingerden’s practice embodies this expanded field. From the late 1990s onward, he abandoned the canvas as the privileged site of meaning, introducing neon, LEDs, and found industrial materials into his vocabulary. These were not merely aesthetic choices but acts of reanimation, objects salvaged from the ruins of deindustrialization, from factory demolitions he himself witnessed and participated in. By integrating these fragments into his work, van Wingerden performs a material resurrection: what once advertised production now illuminates critique.

In Informatie Paradox (2019), the tension between light and language becomes explicit. A composition of neon letters arranged against a dark ground, the piece stages a confrontation between legibility and collapse. The title invokes the paradox of information: the more data we accumulate, the less we understand. Light, here, functions both as revelation and obfuscation, a motif recurring throughout his oeuvre. The neon’s mechanical glow, cold yet seductive, transforms into a metaphor for a culture addicted to visibility yet blind to meaning. In this sense, van Wingerden’s work can be read as a phenomenological critique of the Enlightenment project itself: illumination as deception, progress as paralysis.

A similar ambivalence structures From Russia with Love (2018). Its red neon curves recall both the aesthetic of propaganda and the seductions of nostalgia. The phrase, drawn from pop culture, is charged with irony, the romantic veneer of Cold War anxiety recontextualized within today’s geopolitical cynicism. The letters hover between sincerity and sarcasm, embodying van Wingerden’s fascination with semiotic instability. Here we glimpse the influence of Duchamp’s conceptual wit, yet unlike Duchamp, van Wingerden’s irony is ethical, not nihilistic. The artist’s use of salvaged materials literalizes redemption: the detritus of modern industry becomes the substance of critical reflection.

In Atache Indoctrinatie (2022), the artist turns his gaze toward ideological conditioning. The work, composed of cold neon tubing and layered textual fragments, reads as both a formal study and a moral statement. Its luminous austerity evokes the precise geometry of Dan Flavin, yet the comparison only underscores van Wingerden’s divergence. Whereas Flavin’s fluorescent monuments to space and color celebrated the phenomenology of perception, van Wingerden’s light installations confront the psychology of belief. His neon does not bathe the viewer in transcendental light; it interrogates the sources of that light. The medium becomes metaphor, a technological relic repurposed as philosophical tool.

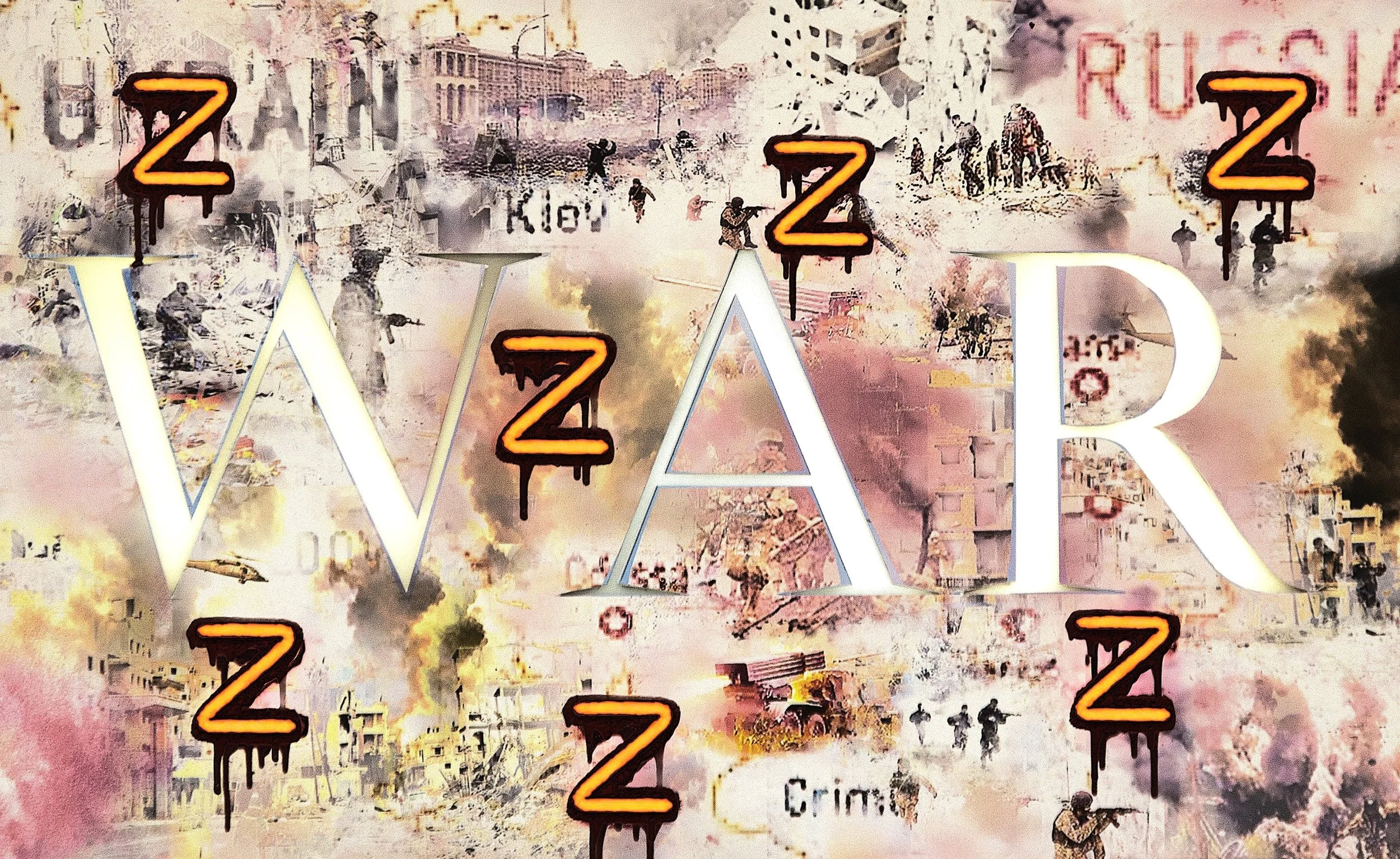

This ethical inversion of minimalism continues in The Z-Word (2023), where van Wingerden uses textual absence as a form of presence. The title suggests censorship, the unutterable, the sign erased by its own violence. Letters, partially visible, are both symbol and scar. It is as if the neon itself hesitates to speak, a broken alphabet of our times. The cool precision of the installation belies its emotional charge. In its restraint, the piece resonates with Adorno’s notion that art after catastrophe must resist beauty to remain true.

If The Z-Word dramatizes silence, Human Rights (2024) embodies resistance. The work’s composition, intersecting neon lines and luminous text, articulates a fragile equilibrium between declaration and disintegration. The word “Rights,” glowing defiantly amid a sea of fractured geometries, becomes both protest and elegy. In van Wingerden’s universe, the political is not external to the aesthetic; it is inscribed in the very ontology of the image. Each flicker of light becomes a moral syllable in a language of conscience.

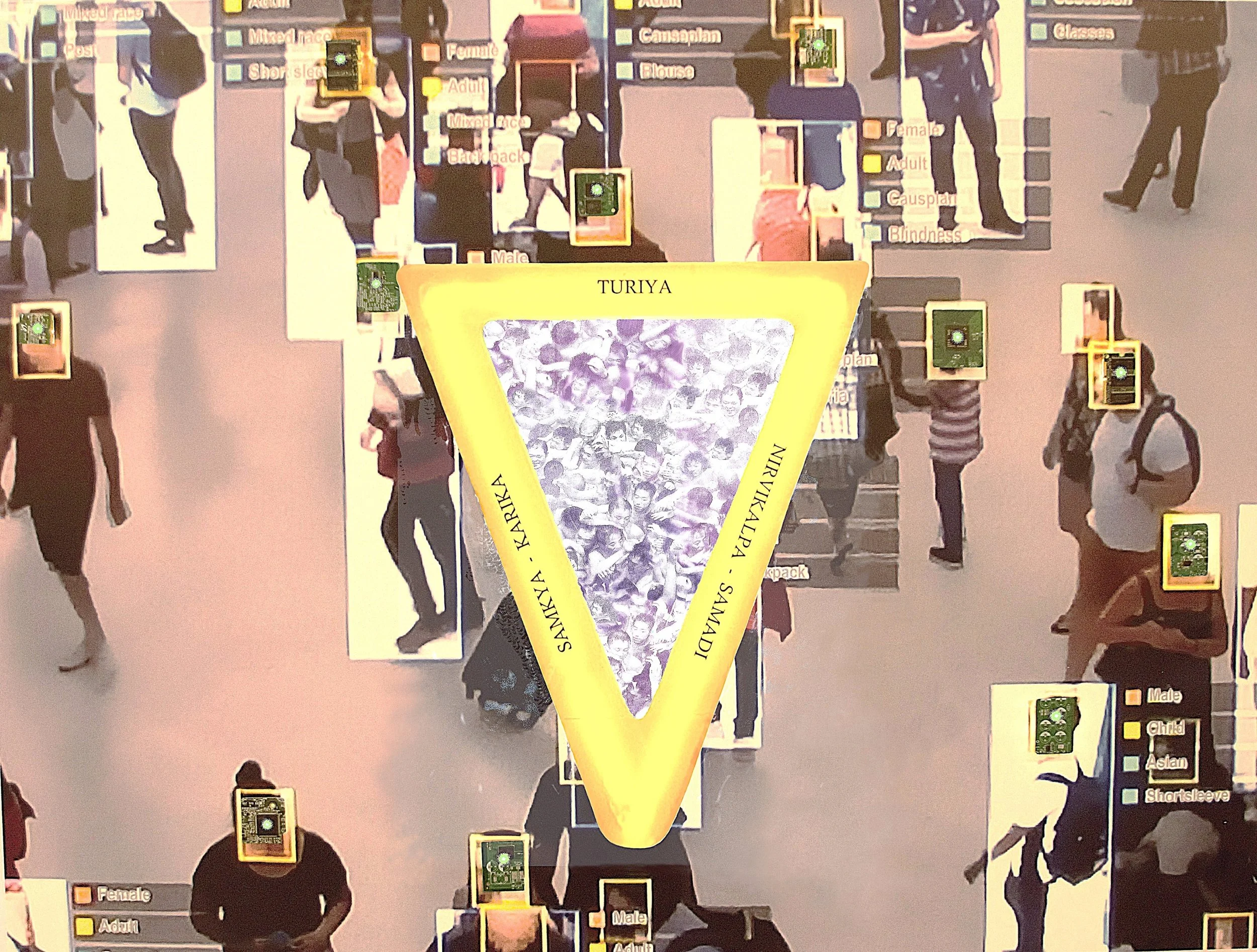

Equally emblematic is FutureStreet (2024), a multi-media LED work that situates light within an urban matrix. Unlike the reflective nostalgia of Pop, van Wingerden’s engagement with technology is critical, even ecological. The street, once a site of encounter, is now algorithmic, illuminated by corporate desire. Yet in reclaiming light from commerce, van Wingerden restores it to thought. The grid that once structured surveillance becomes, in his hands, a structure of possibility.

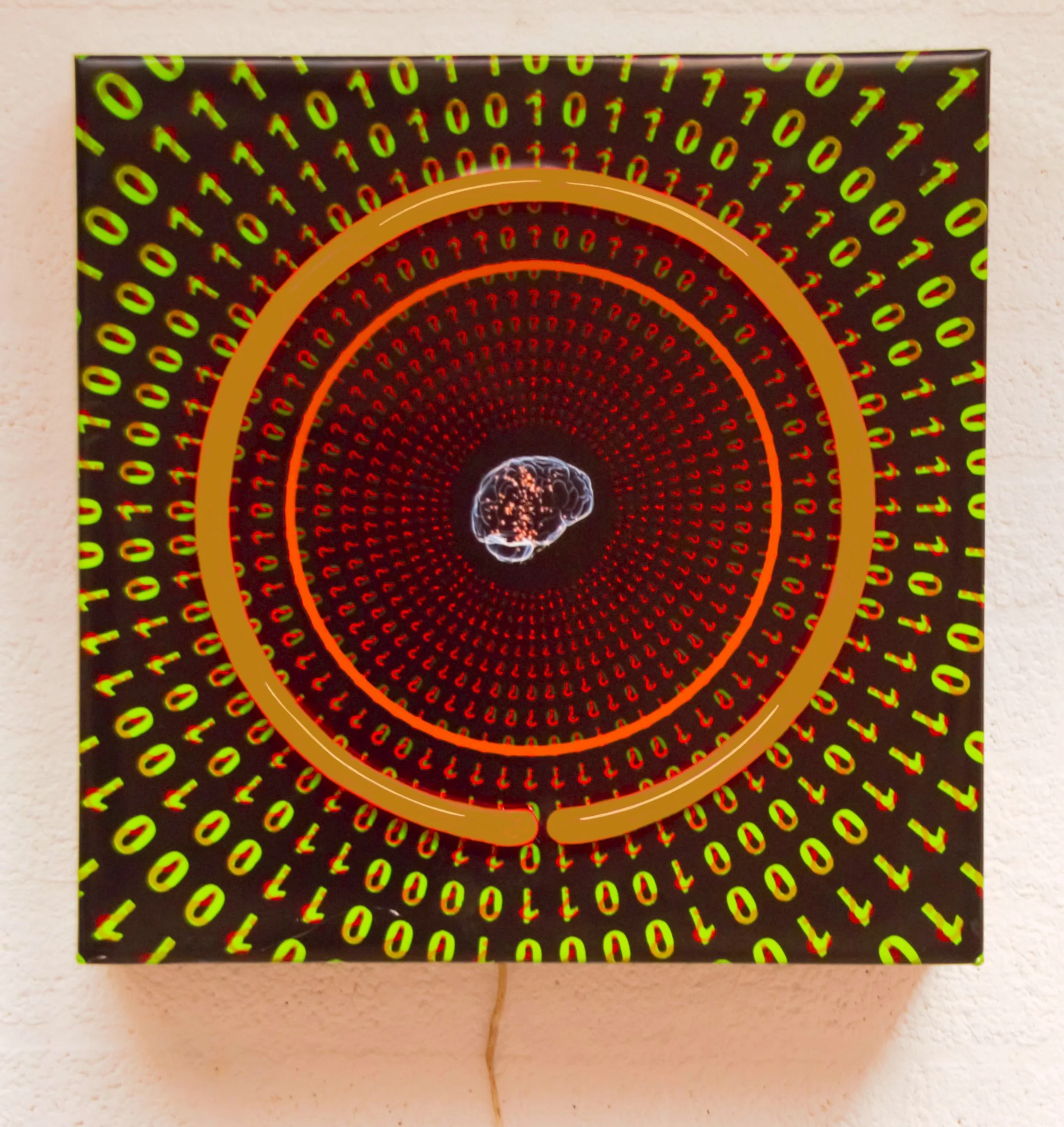

Study for a New Planet (2024) extends this impulse into cosmic metaphor. Combining video, neon, and sculptural form, the work envisions a speculative geography, part utopian and part mournful. The title suggests not escape but reevaluation, a study for re-imagining the conditions of existence. In its slow pulsation of light and motion, the piece achieves a meditative rhythm, reminiscent of the silent rotations of celestial bodies. Yet the glowing circuitry also recalls the fragility of human invention. Here, van Wingerden’s work approaches what one might call metaphysical minimalism, the convergence of technological precision and spiritual inquiry.

By 2025, with works such as The Sixth Dimension (Fine Structure Constant) and Dharma (3 Gunas), van Wingerden’s art enters a stage of transcendental synthesis. In The Sixth Dimension, the artist fuses physics and mysticism. The neon configuration, its angular lines balanced by organic curvature, translates the invisible structure of reality into a perceptual experience. The reference to the “fine structure constant,” a number that determines the strength of electromagnetic interaction, bridges science and philosophy. Light, once merely medium, becomes ontology itself. Krauss might have said that van Wingerden’s practice demonstrates “the post-medium condition,” a state in which material serves thought, not the other way around.

In Dharma (3 Gunas), a two-part oil painting, this inquiry takes a painterly turn. Returning to the medium that launched his career, van Wingerden integrates abstraction with metaphysical symbolism. The three gunas, in Hindu philosophy, denote the fundamental qualities of nature: sattva (balance), rajas (activity), and tamas (inertia). His chromatic fields pulse with these energies, evoking both cosmic equilibrium and psychic tension. The return to painting does not signify retreat but culmination, a reintegration of material and spirit, of the visible and the conceptual.

Throughout these decades, van Wingerden’s oeuvre articulates a coherent philosophical arc, from representation to revelation, from image to idea. His work exists at the intersection of Dan Flavin’s phenomenological rigor, Joseph Beuys’s moral consciousness, and Duchamp’s semiotic play, yet it remains distinctly his own. If Flavin sought to dematerialize sculpture through light, van Wingerden re-materializes ethics through illumination. His neon, unlike Flavin’s industrial purity, carries the residue of history, the ghost of factories, the memory of labor, the melancholy of civilization’s decline. In reclaiming these discarded elements, he performs what might be called an archaeology of the contemporary, each work a site where the material past confronts the ideological present.

Van Wingerden’s commitment to conceptual precision is matched by his sensitivity to perception. His installations are not didactic; they invite contemplation. They operate in what Merleau-Ponty described as “the visible’s invisible,” the space where perception folds into consciousness. The viewer does not merely look at the work but becomes implicated in its logic. The light that illuminates also exposes. One cannot stand before Human Rights or The Z-Word without feeling the ethical disquiet of spectatorship.

To understand van Wingerden’s place in the contemporary art scene, one must look beyond stylistic lineage to philosophical resonance. In an art world dominated by spectacle and market-driven repetition, his practice asserts the primacy of thought. He belongs to a lineage of artists for whom art is an epistemological act, a means of knowing. His works challenge the passivity of seeing, compelling the viewer to think about the image rather than consume it. In doing so, he reinstates art’s critical function in a culture that has largely abandoned critique.

Moreover, van Wingerden’s work embodies a form of ethical ecology, the recycling of discarded materials into new systems of meaning. The neon salvaged from demolished factories becomes a metaphor for redemption, the possibility that even in the ruins of progress, light persists. His art thus speaks to our collective crisis of meaning in the Anthropocene. It reminds us that illumination, both literal and metaphoric, must be earned, not assumed.

If the early avant-gardes sought to collapse the boundary between art and life, van Wingerden’s project might be seen as a reversal: he restores art’s autonomy precisely to re-engage life critically. His works do not imitate the world; they diagnose it. Through a language of luminous restraint, he exposes the hypocrisies of modern civilization, the illusion of freedom, the commodification of truth, and the anesthesia of constant visibility. Yet, for all their critique, his works are not cynical. They carry within them a quiet faith in consciousness, a belief that art can still awaken awareness.

Today, as he continues to produce from his studio in the Netherlands, exhibiting across Europe and earning recognition from museums and private collections, van Wingerden stands as one of the rare artists who reconcile technological sophistication with metaphysical depth. His receipt of the Premier Artist Prize (2025) and Artist Index Prize (2025) only confirms what his oeuvre has long demonstrated: that meaning, when pursued with integrity, still matters.

To encounter Hans van Wingerden’s art is to stand within a field of thought shaped by light. It is to realize that illumination is never neutral, that every act of seeing carries an ethical demand. Like Flavin’s glowing corridors, his works alter the architecture of perception. But where Flavin dissolved the object into pure sensation, van Wingerden reintroduces conscience into the equation. His light is not simply there to be seen; it is there to make us see ourselves.

In this lies his enduring significance. Hans van Wingerden is not merely an artist of forms but of meanings, an alchemist of illumination, transforming industrial residue into metaphysical reflection. In an age of visual excess, he reminds us that the truest light emerges not from what we see, but from what we are finally able to understand.

By Marta Puig

Editor Contemporary Art Curator Magazine

FutureStreet, 2024, Muli/Media/Led, 70 x 70 x 7 cm

The Z-Word, 2023, multi/Media/Neon, 120 x 67 x 12 cm

Atache Indoctrinatie, 2022, Multi/Media/Neon, 34 x 45x 6 cm

Informatie Paradox, 2019 Multi/Media/Neon, 57 x 58 x 15 cm

The Sixth Dimension ( Fine Structure Constant), 2025, Multi/Media/ Neon, 125 x 90 x 15 cm

Study for a New Planet, 2024, Multi/Media/Video, 180 x 60 x 60

From Russia with Love, 2018, Multi/Media/Neon, 90 x 78 x 6 cm,

Human Rights, 2024, Multi/Media/Neon, 60 x 80 x 6 cm

Binnenwereld/Buitenwereld, 1996, oil/canvas,( 2 )x 145 x 150 cm

Dharma (3 gunas), 2025, Oil/Canvas, ( 2) x 80 x 90 cm