Interview with Juliana Kolesova

https://julianakolesova.crevado.com/

Juliana, your work repeatedly stages a tension between figurative clarity and conceptual instability, as if the image insists on being read while simultaneously undoing its own legibility. How do you think about the figure today as a site of knowledge, projection, or resistance, especially after decades in which abstraction and dematerialization were understood as the primary carriers of criticality?

In art, as in many other processes, I see a certain cyclical movement. At one point, figurative painting was declared exhausted, and other forms — abstraction, dematerialization, conceptual strategies — took its place. Today, the pendulum is clearly swinging back, and it is already possible to ask the reverse question: what can abstract painting or the refusal of representation do now, that it has not already done?

I do not find it productive to limit oneself by rejecting either form or content. For me, the figure remains an important tool for thinking — not as illustration or as a carrier of fixed meaning, but as a mobile field of projections, tensions, and interpretations. We cannot say anything fundamentally new in art, but we can offer an unexpected angle, a shift in perspective.

In this sense, figurative art cannot disappear, but it inevitably transforms. It moves away from direct representation toward symbolism, a new expressionism, and a metaphorical, allusive language. It is precisely in this instability — in the figure’s ability to be both recognizable and elusive — that I see its critical potential today.

You have spoken about your paintings as parables without a moral, structures that invite interpretation but refuse closure. In an art world that often demands clarity of position, political, ethical, or autobiographical, what does it mean for you to insist on ambiguity as a form of rigor rather than evasion?

I do not believe that art is always obliged to articulate a specific political or social position. For me, art is a reflection of the artist’s inner world — their ego, if you will, their way of thinking and feeling. Of course, it inevitably resonates with what is happening in the world, but it does so indirectly, rather than through direct commentary.

The artist, in my view, is not a propagandist, nor a commentator on the current agenda in any literal sense. Rather, the artist is a philosopher-observer — someone who registers tensions, doubts, and states of being without reducing them to clear-cut conclusions. In this sense, ambiguity is not a form of evasion for me, but a form of honesty. Reality is complex and contradictory, and it rarely lends itself to unambiguous formulations. Art, I believe, has the right to preserve that complexity instead of simplifying it for the sake of interpretive convenience.

I am not rejecting meaning as such, but I do not think meaning must necessarily be global or declarative. At times, art is a light touch, a detail, a minor experience, a fleeting thought, a metaphor. These seemingly small and personal elements can be no less precise or significant than grand statements. The decision to preserve space for interpretation and uncertainty is, for me, a form of artistic rigor — a demand placed both on myself and on the viewer, an invitation to think rather than to consume a ready-made answer.

Your biography traverses Kazakhstan, Moscow, and Toronto, alongside shifts between fine art, illustration, and applied design. How do these geographic and professional displacements register formally in your work, not as narrative content but as structures of looking, compositional logic, or affective atmosphere?

I believe that moving through the world and attempting to realize oneself in different fields is extremely beneficial for a creative person. For me, geographic and professional displacements are less a source of narrative content than a way of training perception. Each new context adds a new angle of view and forces a different way of looking.

Working across different media — from fine art and illustration to applied design — has shaped a particular compositional logic grounded in attention to structure and function, in how an image operates within space and time. Even when I return to painting or drawing, this experience registers in a certain restraint of decisions, in the clarity of construction, and in an interest in details that might initially appear secondary.

Alongside visual practices, I write poetry and prose and experiment with essays, interior design, and craft. This interdisciplinary movement expands not only my technical vocabulary but also my range of sensitivity. It affects the atmosphere of the work — its tone, density, and tempo.

Many of your images seem to hover in a suspended psychological state, neither fully narrative nor entirely symbolic. How do you understand time operating in your paintings, as frozen duration, cyclical return, historical residue, or something closer to ritual?

To be honest, I have never consciously thought about time as a category in my work. However, reflecting on your question, I realize that the temporality in my paintings is probably closer to a ritualistic or dream-like time, rather than a linear or narrative one. The images exist outside of progression or resolution; they do not move forward, but linger.

This sense of suspension allows the paintings to operate as spaces of repetition and presence, similar to a ritual, where meaning emerges through duration rather than sequence. Time in this context is not something that passes, but something that is entered—experienced intuitively rather than understood chronologically.

You have described your attraction to applied arts, historical costume, and craft traditions as a form of real mysticism. In what ways do you see these historically marginalized or utilitarian practices as carriers of cultural memory that resist the linear narratives of canonical art history?

In my view, applied arts offer one of the most honest reflections of human self-awareness and the mystical dimension of culture. Unlike canonical art history, they are not primarily driven by political agendas, moral frameworks, or the need to articulate a position. Instead, they emerge from everyday necessity, ritual, and embodied knowledge.

Because of this, applied and craft traditions carry cultural memory in a non-linear way. They preserve gestures, symbols, and techniques across generations without requiring historical justification or narrative coherence. This creates a natural continuity of time—an intuitive transmission rather than a documented one.

For me, this is where their mysticism lies.

Your work often balances elegance with disturbance, beauty with unease, irony with sincerity. How deliberate is this oscillation, and do you see it as a way of challenging the viewer’s desire for aesthetic comfort or moral alignment?

I would say that this oscillation is very deliberate, but not calculated in a programmatic way. It emerges from a conviction that art is not meant to soothe, reassure, or offer a stable moral position. Comfort and alignment belong more to design, decoration, or ideology. Art, as I understand it, operates in a different register — one where contradictions are allowed to coexist without being resolved.

The tension between elegance and disturbance is important because beauty has a seductive power: it draws the viewer in, lowers their defenses. Unease, on the other hand, interrupts passive consumption. When these two states exist together, the viewer is prevented from settling too quickly into approval, identification, or rejection. They are asked to remain present, to tolerate ambiguity, and to question why they want clarity or comfort in the first place.

Irony and sincerity function similarly. Irony creates distance and awareness, while sincerity risks exposure and vulnerability.

In that sense, the work does challenge the desire for aesthetic comfort and moral alignment — but not as a provocation for its own sake. It’s an attempt to reflect the complexity of lived experience, where beauty is not always innocent, discomfort can be productive, and moral certainty is often an illusion. Art, for me, becomes a site of sustained attention rather than resolution, asking the viewer not to agree, but to stay with what unsettles them.

Having produced thousands of illustrations alongside your personal studio practice, how has working within the constraints of commercial and editorial contexts reshaped your understanding of authorship, originality, and the autonomy of the image?

Working in commercial and editorial illustration has made me acutely aware of the need to maintain a clear distance between applied work and my personal practice. Commercial images are shaped by briefs, collaboration, and function; authorship is shared, and originality operates within predefined limits.

My own work exists deliberately outside of this structure. It is a space where the image does not need to explain or serve, and where authorship remains fully personal. Protecting this separation is essential to preserving originality and allowing the work to express my own personality.

Rather than conflicting, these two modes reinforce one another: commercial work sharpens discipline and clarity, while personal practice safeguards autonomy and keeps the work self-directed and alive.

You have suggested that once a work is finished, the artist’s intention becomes irrelevant, replaced entirely by the viewer’s interpretation. How do you reconcile this position with the unmistakable coherence of your visual language, which suggests a highly disciplined and intentional construction?

I don’t see a contradiction here — one does not exclude the other. There is no refusal of intention or discipline in my practice. On the contrary, clarity of the image and control over meaning are essential starting points for me. When I’m making a work, I know very precisely what it is about, what tension it carries, and why each element is there. Without that internal coherence, the work would simply collapse.

But intention, for me, belongs to the process of making, not to the life of the work once it is finished. The discipline and coherence you notice are not there to deliver a message, but to create a stable structure — something solid enough to be looked at from many angles. I try to avoid directness because directness closes interpretation too quickly. It tells the viewer where to stand and what to think.

What interests me is not confusion, but openness. I don’t want to guide the viewer or leave interpretive “instructions” inside the image. If the work is precise, it’s precisely so that the viewer can enter it with their own experience, their own associations, and see something I may not have anticipated. In that sense, authorship ends where perception begins.

So it’s not so important what I wanted to say. What matters is what the viewer is able to see — how the work resonates, shifts, or refracts meaning through their gaze. The image is intentional in its construction, but free in its consequences.Your paintings frequently evoke art historical echoes, medieval icon painting, magical realism, and surrealism, without functioning as quotation or pastiche. How do you negotiate the difference between historical resonance and historical nostalgia in your practice?

For me, the past is neither decoration nor a reason for nostalgia. It is not meant as a “pretty background” or a stylistic toy. The past is a cultural foundation, knowledge, and roots without which nothing can grow. It is the historical memory of humanity, and there is no escaping it.

When I work with historical forms or visual traditions, I do not aim to quote or stylize them. I use them as a source of strength and understanding, as a base upon which contemporary imagery is built. This allows for resonance with the past — not in the sense of nostalgia, but as a living dialogue. The past becomes a partner to reflect with, rather than an object of sentimental memory.

In your work, the human body often appears as a site of transformation, melting, merging, or subtly destabilized. Do you see the body primarily as a psychological container, a cultural artifact, or a metaphysical threshold?

Yes, I understand the human body—like everything else in my work—as a partially symbolic, conceptual, or emotional object. These dimensions are not fixed or hierarchical; their proportions shift from image to image.

Rather than representing the body as a stable form, I’m interested in its capacity to carry multiple registers at once. It can function simultaneously as a site of emotion, a bearer of cultural meaning, and a conceptual structure. This instability allows the body to become a threshold rather than an endpoint—something that opens the image to transformation instead of closure.

You have described the creative process as alchemical, marked by irritation, anxiety, and impatience before resolution emerges. How important is uncertainty to your practice, and do you think true risk is still possible within a mature, highly developed visual vocabulary?

Uncertainty is important—that is precisely why I describe the process as alchemical. I can begin a work with the feeling that I am in control, relying on experience and a developed visual vocabulary, but at a certain point something shifts. The process starts to assert its own logic, and I realize that I am no longer fully directing it.

This loss of complete control is where real risk still exists for me. Even within a mature practice, the outcome is never entirely predictable. Materials, images, and decisions begin to interact in ways that cannot be fully planned, and I have to respond rather than impose.

Alchemy, in this sense, is not about mastery but transformation. The work only resolves when I allow uncertainty to guide it, accepting that the process can—and sometimes must—take over.

Your refusal to assign a special social role to the artist runs counter to many contemporary discourses around activism and didacticism in art. Do you see this stance as a form of resistance, withdrawal, or simply realism about what images can and cannot do?

I’ve already partly addressed this question, but I would add that I’m not refusing anything in principle. An artist can absolutely be an activist, or take on any other social role, and I don’t see that as a contradiction. In my own work, explicitly social or political themes also appear when there is a genuine need to speak about them.

For example, my recent series Leaders, shown at the Florence Art Biennale at the end of last year, engages directly with the philosophy of power. However, for me the starting point is always an honest account of my own experience, however strange that may sound. Without that internal necessity, social themes risk becoming illustrative or didactic.

So my position is not withdrawal or resistance, but realism about what images can do. I believe that images are most effective when they emerge from personal truth rather than obligation, and that their social resonance grows precisely from that honesty.

The tonal darkness often attributed to your work is counterbalanced by moments of subtle humor and irony. How do you think humor functions in relation to disturbance? Does it disarm the viewer, sharpen the critique, or complicate emotional identification?

Irony is, for me, an essential element both in life and in art. Almost everything has at least two sides — a light and a dark, a sad and a funny one. Learning to recognize both is a valuable skill; it allows us to approach the world philosophically and understand it better.

In my work, depending on the idea, I allow for the full spectrum of expression — from gentle, good-natured humor to sharp, biting sarcasm. Humor and irony do not merely disarm or entertain; they create a space for reflection, letting the viewer experience complexity without forcing a single emotional response. They acknowledge the contradictions of life, reminding us that even in darkness there can be levity, and even in levity there can be insight.

Regarding the perceived darkness in my work, I think it's only a first impression. What may seem obscure, unsettling, or somber at first glance actually holds layers of subtlety. If you look closely and think about it, nuances begin to emerge from this gloom: sadness, doubt, contradiction …

Someone once remarked that my work isn’t about darkness—it’s about pain. I tend to agree.

Across painting, digital work, and photography, your images retain a consistent psychological density. What determines your choice of medium in a given work, and do you think medium still carries ideological weight in a post-medium condition?

I don’t believe that the choice of medium carries inherent ideological meaning. For me, a medium is simply a tool. What truly matters is the concept—the thought or internal necessity behind the work. The medium is chosen pragmatically, based on what allows that idea to be articulated most clearly or efficiently.

Because of this, moving between painting, digital work, and photography feels natural rather than strategic. The psychological density you mention comes from the continuity of thinking, not from the material itself. In that sense, I do think we are living in a post-medium condition, where ideas lead and the means of expression remain secondary.

If your works are invitations to dialogue rather than statements, what kind of viewer do you imagine completing them, not demographically but intellectually and emotionally, and how much responsibility do you believe the viewer bears in activating the deeper layers of the image?

I don’t imagine a specific type of viewer. The viewer can be anyone, and their interpretations can be completely different. That said, ideally, we are always searching for a kindred mind—someone who is willing to engage openly rather than seek fixed meanings.

When it comes to responsibility, I don’t believe that either the artist or the viewer owes anything to the other.

A dialogue either happens or it doesn’t. I often say: don’t ask what the artist wanted to say. The work has already said exactly what you were able to hear.

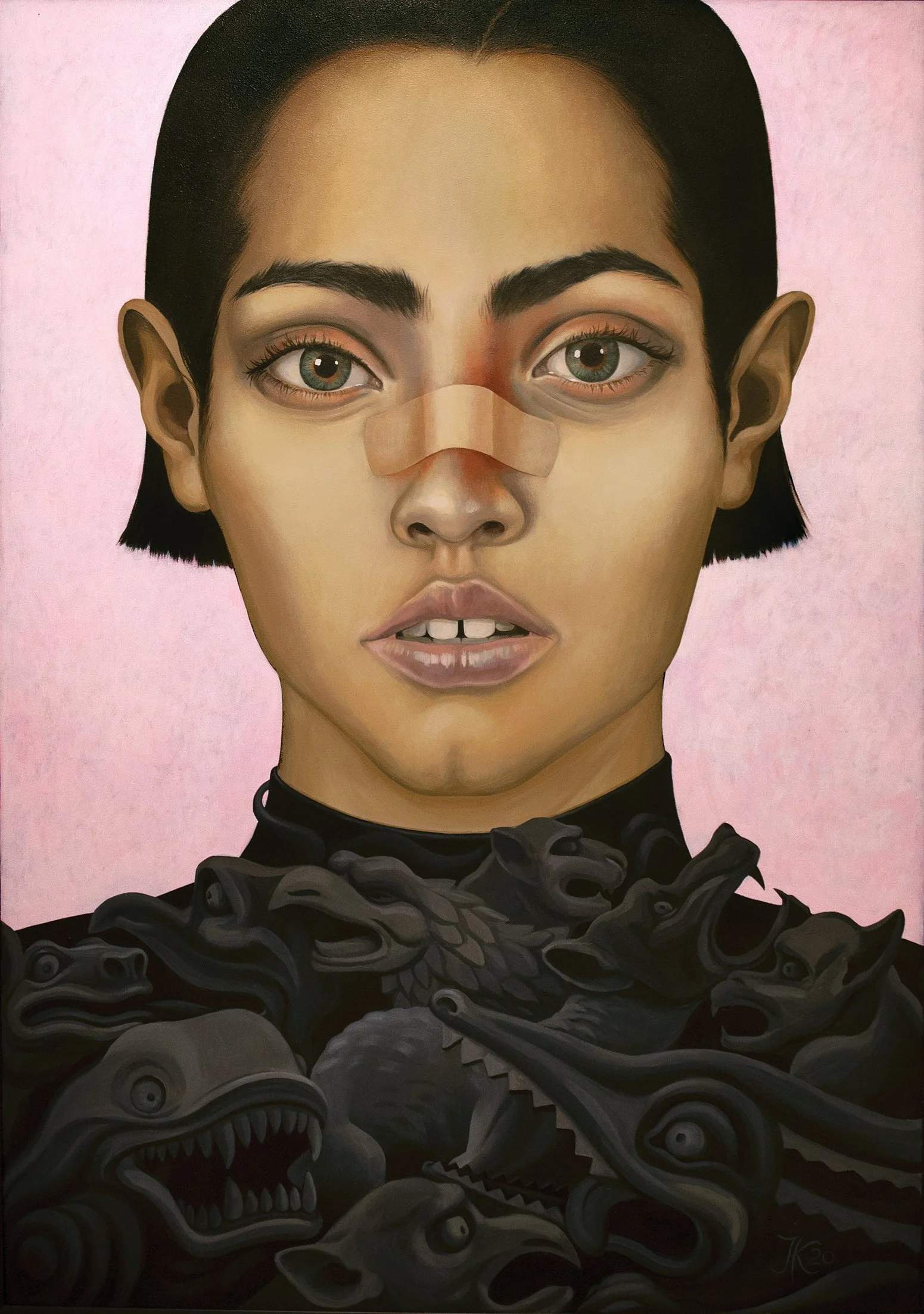

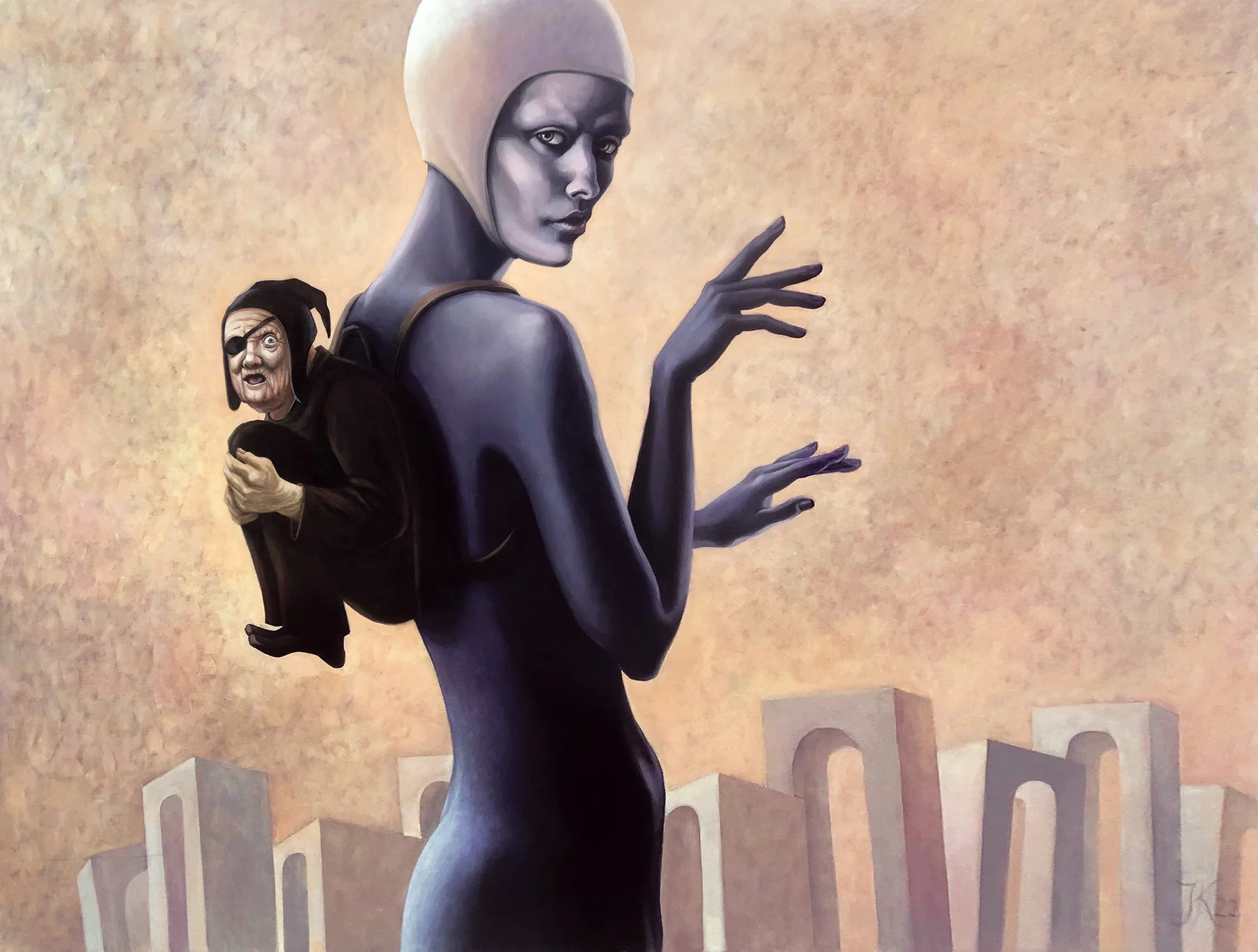

The Sky Is Pink Acrylic on Board 96.5” x 137” cm

Growing Up Acrylic on Board 40.5 x 127 cm

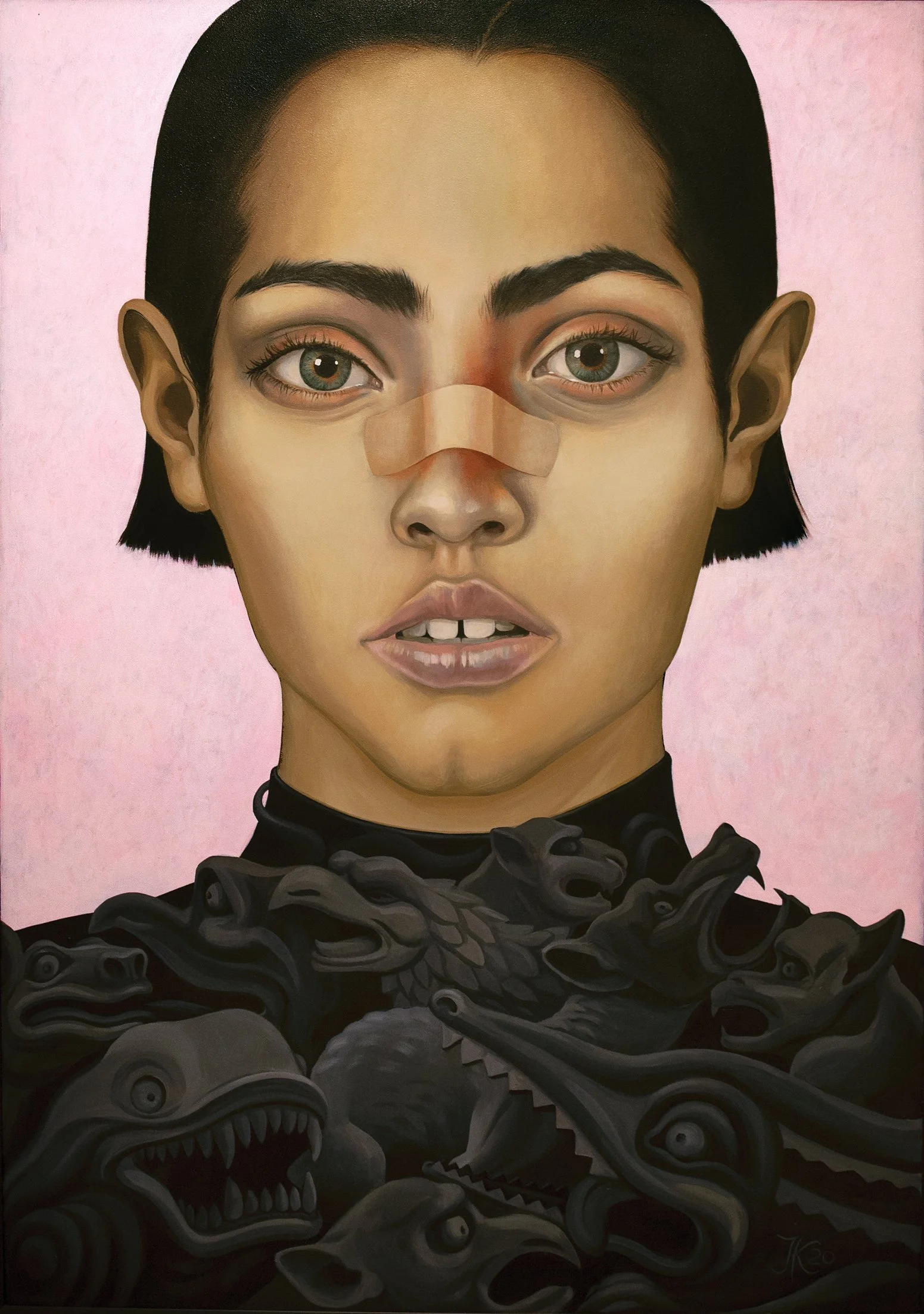

Under the Lemon Sun Acrylic on Canvas 101.5 x 101.5 cm

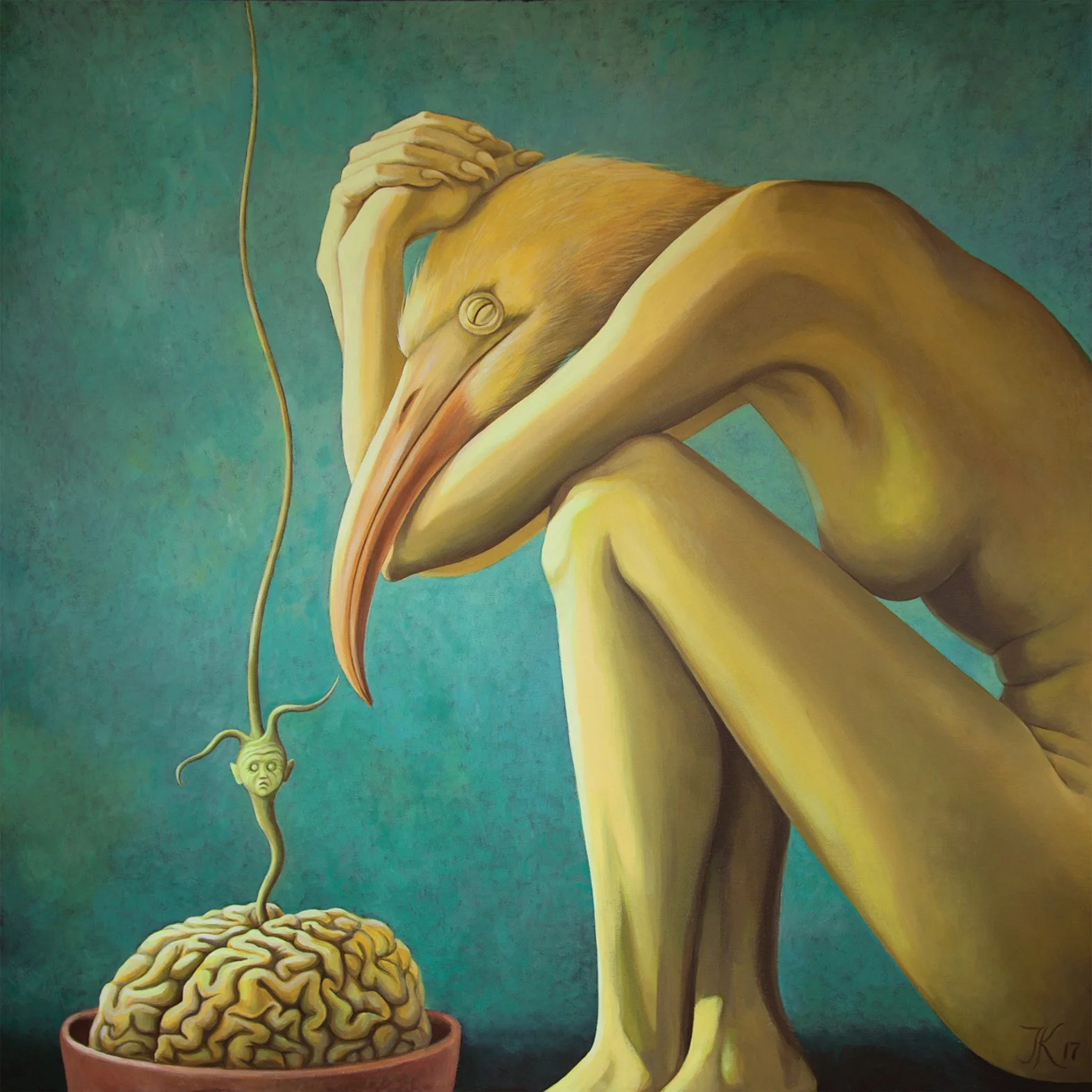

Blue Light Acrylic on Canvas 122 x 122 cm

Innocence of Creativity Acrylic on Canvas 101.5 x 101.5 cm

Grain of Truth Acrylic on Canvas 101.5 x 101.5 cm

Poet and His Muse Acrylic on Canvas 101.5 x 101.5 cm

The Bird of Happiness Acrylic on Canvas 101.5 x 101.5 cm

Masks Oil on Canvas 76 x 101.5 cm

Woman Carrying Her Years to Come Acrylic on Canvas 91 x 121 cm

In Harmony with Nature Acrylic on Canvas 61 x 121 cm

The Sun Holders Acrylic on Canvas 99 x 99 cm

Ego Acrylic on Canvas 91 x 121 cm

Fruit of the Tree of Knowledge Acrylic on Canvas 76 x 119 cm

Family Portrait with Pomegranates Acrylic on Canvas 88 x 141 cm