Interview with Frank Mayes

https://acmeaestheticsfrankmayesart.com/

Frank, how does your concept of implied detail function not only as painterly strategy but as a philosophical position on perception, where the viewer completes what the image withholds, and realism becomes an act of negotiation rather than confirmation?

My implied detail is actually detail, but not photographic detail. A viewer may get real close to a painting and look at the brush work. It’s very loose compared to viewing or relating to a photo realistic painting. When the viewer moves back…say 5 to 8 feet the painting comes alive as a complete work. There is no negotiation, the viewer either get’s it or doesn’t. We all form our own realism, the painter just needs to tell the story.

Woman With Gold Leaf Oil on canvas 30 x 40 inches

After sustained study within institutions such as the Uffizi, the Louvre, and the Met, how has long exposure to canonical works reshaped your understanding of authorship, tradition, and the temporal responsibility of painting today?

I studied the masters paintings in order for me to create a better painting. As to temporal responsibility, I indirectly use my time to advance the genre of realism, in all of its different manifestations. Since the great ivory towers of learning have embraced in total, abstract expressionism, first promoted by the CIA in 1947, I just don’t fall into that category. It isn’t necessarily a responsibility, I just live in an art world where the artist know how to draw, and realism isn’t a bad word.

my understanding of authorship and tradition has evolved into a more nuanced perception. Long exposure to these works reveals the layered dialogues across centuries—how artists have engaged with their predecessors, reinterpreted themes, and challenged conventions. This immersion underscores that authorship is not solely a matter of individual originality but is deeply intertwined with tradition as a living conversation.

Furthermore, witnessing the craftsmanship and contextual depth of these masterpieces deepens my sense of the temporal responsibility inherent in painting today. It prompts a consciousness that contemporary artists are custodians of a continuum—bearing the legacy of past masters while also contributing to ongoing cultural dialogues. The responsibility lies in honoring tradition not as mere replication but as an active engagement that pushes boundaries and explores new meanings, ensuring that the language of painting remains vital and relevant in our current moment.

Grandmother Knotting Her Shaw Oil on canvas 30 x 24 inches

Your comparison between painterly distance and digital zoom suggests a visual logic rooted in contemporary modes of seeing. Do you consider this approach a critique of screen-based perception, or a reconciliation between classical painting and digital consciousness?

I see the comparison between painterly distance and digital zoom as a nuanced reflection on how we perceive and engage with images in contemporary culture. Rather than framing it solely as a critique of screen-based perception, I consider it an attempt to reconcile—perhaps even blur—the boundaries between classical painting and digital consciousness.

Painterly distance historically emphasizes the tactile, material, and spatial relationships within a painting, encouraging slow, contemplative viewing. Digital zoom, on the other hand, fragments and accelerates perception, emphasizing immediacy and hyper-focus. By drawing parallels between the two, I aim to highlight how both modes shape our understanding of visual depth, proximity, and meaning—each influencing how we inhabit images.

This approach suggests that contemporary seeing is not purely adversarial but interconnected. It recognizes that digital modes are an extension of our visual language—altered but not wholly disconnected from traditional painterly concerns. Ultimately, I see it as a reconciliation: an acknowledgment that classical notions of depth and perspective can coexist with, and even inform, digital modes of perception, creating a layered, hybrid visual logic suited to our modern experience.That taps directly into the tension between perception and narration in both painting and digital representation. If we look at light not merely as illumination but as a narrative vector, it becomes a structuring agent that orders attention, emotion, and temporality without recourse to explicit story. In painterly or photographic terms, light defines not just what we see, but how we see — it shapes hierarchy, rhythm, and the psychological weight of an image.

Light in your work operates structurally rather than atmospherically, shaping hierarchy, silence, and attention. How do you conceive light as a narrative force capable of directing meaning without explicit storytelling?

In my paintings, light most often defines forms and composition, shaping volumes, guiding the viewer’s eye and determining the hierarchy of elements.

So, light becomes a narrative force by structuring what can be seen. It marks zones of authority, creates moments of silence through darkness, and channels gave toward designated focal points. In practice, this means designing light paths that guide eye movement, using shadows to mute peripheral activity, and employing luminous “traces” that linger as visual memory, an implicit storytelling that shapes meaning through the very architecture of illumination.

Me and My Monkey Or What’s Next Oil on canvas 24 x 48 inches

Your realism resists photographic hardness while avoiding sentimentality. How do you calibrate restraint and emotional accessibility, particularly when working at a monumental scale where gesture risks becoming declarative?

In my paintings, “Generally” restraint comes from controlling elements like color palette, brush work, and composition. Emotional accessibility relies on how I use light, subject, and expressive details. Emotion comes from directing the viewer’s eye with contrast, gesture, or atmosphere. The actual restraint comes from the real subject of the painting and how I decide to express it.

I treat realism as a “visual story‑telling” discipline that leans on careful observation rather than the glossy certainty of a photograph. I am realist painter…a visual story‑teller” who lets the scene breathe instead of forcing a narrative, a stance that automatically curbs sentimentality and keeps the image from slipping into photographic hardness. I achieve restraint by limiting gestural flourishes to the essential line or brush‑stroke that suggests movement, and by using a muted, tonal palette that conveys mood without overt dramatics. At the same time, my work “pulses with life” and “invites viewers to step back and let the story unfold,” a quality he creates through subtle contrasts of light, texture and composition that give the viewer an emotional foothold without the artist dictating feeling.

When the canvas expands to a monumental size, I let the larger surface become a stage for quiet, controlled gestures rather than a platform for declarative statements. I “pull you into scenes that feel simultaneously familiar and otherworldly” by maintaining a balance between observation and emotion—using scale to amplify detail and atmosphere, while preserving the same restrained brushwork that characterizes my smaller works. In practice this means planning the overall composition first, then applying only the necessary expressive marks, allowing the sheer size of the painting to carry the weight of the gesture and letting the viewer’s own perception supply the emotional resonance. The result is a realism that remains accessible and moving, yet never crosses into melodrama, even on a grand scale.

The Western and Lakota Sioux paintings occupy a complex ethical space between representation, reverence, and narrative authorship. How do you position yourself within this tension while remaining a visual storyteller rather than an ethnographic observer?

I have met, befriended and lived with a member of the Mni Kuju band of the Teton Lakota Sioux. I have had the honor of joining in their tribal ceremonies. Ron Eagle Chasing has taught me much about the Lakota Sioux. Their honor system, their religion, and their relation to mother earth. He gave me my Sioux name “ Etah Iniechupi.“ The culture of the Lakota Sioux has created a very reverent being in my self.

Ultimately, I remain a visual storyteller by embracing the ethical tension: I avoid the “camera‑like” freeze of the past that early ethnographic photography imposed, and instead create work that invites multiple voices, respects Lakota values of generosity and fortitude, and contributes to a broader, community‑driven narrative of the Plains . This stance keeps the focus on storytelling rather than observation, allowing the paintings to serve as bridges between cultures rather than objects of scholarly scrutiny.

Black Hills Dancer Oil on canvas 40 x 30 inches

Travel in your practice appears less as subject matter than as a cognitive catalyst. What determines whether a place resolves into a singular image or unfolds into a sustained series of works?

It depends on the depth of understanding and involvement in where I am visiting. I am always emotionally awakened by the history of art and the creators that have been and passed. For example, when ever I’m in Florence I always visit Santa Croce and pay homage to Michelangelo Buonarroti. The last time in Italy I went to the small town of Vinci to visit Leonardo da Vici’s birth place. When leaving the small town/village of Assisi, the evening light took over my reality… I knew it would be a painting.

For me, the journey itself is not just a physical or geographical one, but a deeply personal and introspective process. As a visual storyteller, I find that the places I travel to often become imbued with a sense of emotional resonance, which can either coalesce into a single, defining image or unfold into a more complex, narrative-driven series.

The determining factor often lies in the interplay between the site itself, my own emotional connection to it, and the creative momentum that builds as I engage with the place. If I feel a strong, intuitive sense that a particular location or experience is begging to be distilled into a singular, powerful image, then I may focus on capturing that essence in a single, striking work. However, if I feel that the experience or location is more layered, complex, or open-ended – if it invites multiple perspectives, histories, or emotional responses – then I may choose to explore it through a series of works, allowing each piece to reveal a different facet of the place or its significance to me. Ultimately, the decision to resolve a place into a singular image or unfold it into a series of works is guided by a combination of creative instinct, the demands of the site itself, and the narrative threads that begin to emerge as I engage with the place on a deeper level.

Leaving Assisi Oil on canvas 20 x 16 inches

Your movement between intimate formats and mural scale alters both time and bodily engagement. How does scale recalibrate your relationship to duration, labor, and viewer absorption?

In my oil paintings, the scale directly affects how the viewer’s perception of time and labor are perceived and how a viewer engages with the painting. A large scale painting, such as “The Buffalo Dreamer Dances,” shows extended time of working on the painting. The viewer seems to feel the hours and hours of creating the painting. It invites the viewer to step back, move around, and spend more time with the painting.

While a small scale painting, condenses the time spent working on the painting, and requires a closer viewing of the painting. It focuses the viewers attention in a tighter more intense frame of engagement.

So, Scale recalibrates both my temporal investment and the viewers temporal experience of the work.

The Buffalo Dreamer Dances Oil on canvas 6 feet x 4 feet

You often speak of storytelling while allowing narratives to remain partially obscured. What role does ambiguity play in your work, and how do you understand opacity as a form of respect for the viewer’s interpretive agency?

In my paintings opacity means using the layers of paint to conceal or reveal what is beneath. The opaque layers cover what came before, while the transparent layers let the underpainting show through. While the ambiguity of the elements of my painting require the viewer to make up their story. Ambiguity is a deliberate choice in my work, as I believe it allows the viewer to step into the narrative and become a co-creator of meaning. By leaving some elements open to interpretation, I'm not trying to control the viewer's experience or dictate a single, definitive reading. Instead, I'm inviting them to bring their own perspectives, experiences, and emotions to the work. Opacity, in this sense, becomes a form of respect for the viewer's agency. By not spelling everything out, I'm acknowledging that the viewer has their own story to tell, their own connections to make. I'm not trying to fill in the gaps or provide a clear, linear narrative. Instead, I'm creating a space for the viewer to explore, to imagine, and to make their own meaning.

This approach also honors the complexity of real life, where stories are rarely neat, tidy, or easily summarized. By embracing ambiguity, I'm reflecting the messy, multifaceted nature of human experience, where multiple narratives often intersect and overlap.

In a way, I see my work as a kind of invitation to the viewer: to enter the space, to engage with the imagery, and to create their own narrative. By not providing all the answers, I'm allowing the viewer to become an active participant in the storytelling process, and that, to me, is a fundamental aspect of the creative act.

The buffalo dreamer Oil on canvas 6 feet x 4 feet

Music runs parallel to painting in your life rather than existing as background. Do rhythm, tempo, and musical structure consciously shape your compositional decisions, or do they function as an internal discipline guiding studio time?

I’ve played music almost as long as I’ve been painting. Music, when you get far enough into it becomes another language. In my painting studio, music is a meditative assistant, helping me to completely immerse myself the flow of painting

Music is an integral part of my creative process, and one that I’ve honed over years of playing and painting. The fact that I state music is a "language" acknowledges a deep level of understanding and connection to it, which in turn influences my approach to painting. I describe music as a "meditative assistant" in the studio. This says that music serves as a tool to help access a flow state, where I’m fully immersed in the act of painting and able to navigate the creative process with greater ease. In this sense, it's not necessarily that rhythm, tempo, and musical structure are consciously shaping compositional decisions, but rather that they're creating a subtle, underlying framework that informs my work. The internal discipline, honed through years of playing music, is guiding my studio time, allowing me to move through the creative process with greater fluidity and intention.

It's almost as if my musical background is creating a kind of "cognitive architecture" that underlies the painting practice. This architecture influences the way I think about composition, color, and form, but in a way that's so deeply ingrained that it's almost unconscious.

The Ponte Vecchio Oil on canvas 28 x 22 inches

Your engagement with so-called deviant art and AI introduces speculative processes into a historically grounded practice. How do you reconcile technological experimentation with the tactile intelligence and resistance of paint?

I’ve played with Ai generated subjects… it’s a tool. I categorize my deviant art, as something like recess or play time. I don’t necessarily paint heavy meaning or thoughts into my Deviant paintings. They are just a fun time in oil paint, there but anything to reconcile, both can be an end to a creative process.

For me, the reconciliation of technological experimentation with the tactile intelligence and resistance of paint is a dynamic, iterative process. I believe that the qualities of paint – its materiality, texture, and unpredictability – are precisely what make it an ideal partner for exploring the frontiers of digital art.

When I engage in deviant art and AI, I see it as an opportunity to re-examine the fundamental relationships between artist, medium, and process. The introduction of technology and AI into my practice introduces new variables, new possibilities, and new challenges.

I've come to understand that the tactile intelligence of paint is not diminished by the incorporation of digital tools, but rather, it's amplified and extended. The resistance of paint becomes a catalyst for exploring new ways of working with AI, and the AI, in turn, becomes a collaborator that helps me to push the boundaries of what paint can do.

In many ways, the use of AI is a way of tapping into the potential of paint as a material, rather than simply relying on traditional techniques. By embracing the uncertainty and unpredictability of both paint and AI, I'm able to create new, hybrid forms of art that are distinct from both the digital and the analog.

Ultimately, my goal is to create a dialogue between the physical and the digital, one that blurs the lines between medium and medium, and challenges the viewer to re-evaluate their relationship with the artwork. It's a process that's both meditative and exhilarating, and one that I feel is still unfolding.

Death Dealer on Broadway Oil on canvas 20 x 16 inches

The physical rigor of your process, from stretching linen to exhausting brushes, suggests an ethic of material endurance. How does this commitment to making information inform your sense of legacy and permanence?

It’s the responsibility of the artist to use quality products and methods to create for the long time endurance. It’s how I create art. The factors have little thought and aren’t relevant.

This commitment to making is not merely about the final image but about engaging with the tangible, labor-intensive act of creation. It’s an acknowledgment that meaning is rooted in effort, time, and the physicality of materials.

This process cultivates a sense that legacy isn’t solely defined by the permanence of the work’s presence but also by the endurance of the act itself. The repeated, deliberate engagement with materials becomes a form of ritual—an embodied act that resists the ephemeral nature of digital or fleeting experiences. In this way, the labor-intensive process transforms the painting into a testament to persistence, where the physical investment imbues the work with a kind of temporal weight. It affirms that true permanence emerges from sustained effort, making the act of creation itself a form of ongoing legacy—one that acknowledges the wear and tear of time as integral to its meaning.

Many of your influences are painters associated with narrative clarity and emotional immediacy. How do you position your work within that lineage without slipping into nostalgia or illustrative closure?

I don’t position my work except in the genres that I work in. I in fact, sometimes I very purposely involve nostalgia in my paintings… It is

something from my life. It is a part of me that I remember fondly, and in part what I want people to know about me. For an example, the multi panel painting “ I Grew Up Here “ is a painting from Pensacola Beach. I surfed and played on P’cola Beach until I finely left home to see the world. The viewer doesn’t know about the things that happened and they just know the sand, the water and the sky. The people that know me know the stories and the events that took place there at the beach.

I use Illustrative closure often in my paintings. When I paint a scene or image, it can imply a complete visual story, even if I’ve left out parts of the story. That allows the viewer to fill in the missing details.

I Grew Up Here Oil on canvas 24 x 48 inches

When your work is encountered across different geographic and cultural contexts, what variations in interpretation have most challenged or surprised you, and how do those readings feed back into your practice?

I really haven’t experienced this. In my paintings, most are a very literal presentation of the subject. A viewer can’t look at an apple in a painting and see an orange. It’s the same in my paintings. As to the “readings “ of my paintings, when last in Florence, I was attending a workshop at the Accademia del Giglio. Several of the instructors viewed my work… They didn’t have any problem with the interpretation of my paintings, at the time, they seemed to be more interested in the size and painting hours than just the subject. You get to a point especially with other artist that art is art…thus a painting is a painting. They like it or they don’t.

Across continents, viewers often read my paintings through the lens of their own cultural narratives. In the American Midwest, audiences familiar with Lakota heritage tend to see my depictions of tribal dancers as a living archive that honors an “ageless culture,” while in coastal galleries the same canvases are described as “emotion‑filled landscapes” that evoke a universal sense of place and In European settings, critics emphasize the “immersive brushstrokes” and the dialogue the work creates between observer and painter, interpreting the realism as a bridge between the familiar and the otherworldly. These divergent readings—historical documentation, emotional topography, and immersive storytelling—have repeatedly surprised me, especially when a single piece is simultaneously praised as a cultural testimony and as a purely aesthetic experience.

Each reinterpretation feeds back into my practice by expanding the narrative scope I pursue. Knowing that a Lakota figure can also function as a universal symbol of resilience encourages me to deepen the cultural research behind each subject, while the emotional resonance noted by coastal viewers pushes me to heighten atmospheric qualities in my landscapes. My extensive travel and exposure to varied world views, which I credit for broadening my own perspective, now become a deliberate tool: I incorporate feedback from disparate audiences to weave richer, more layered stories that speak both to specific histories and to shared human experience. This ongoing conversation ensures that my realism remains a living, evolving dialogue rather than a static representation.

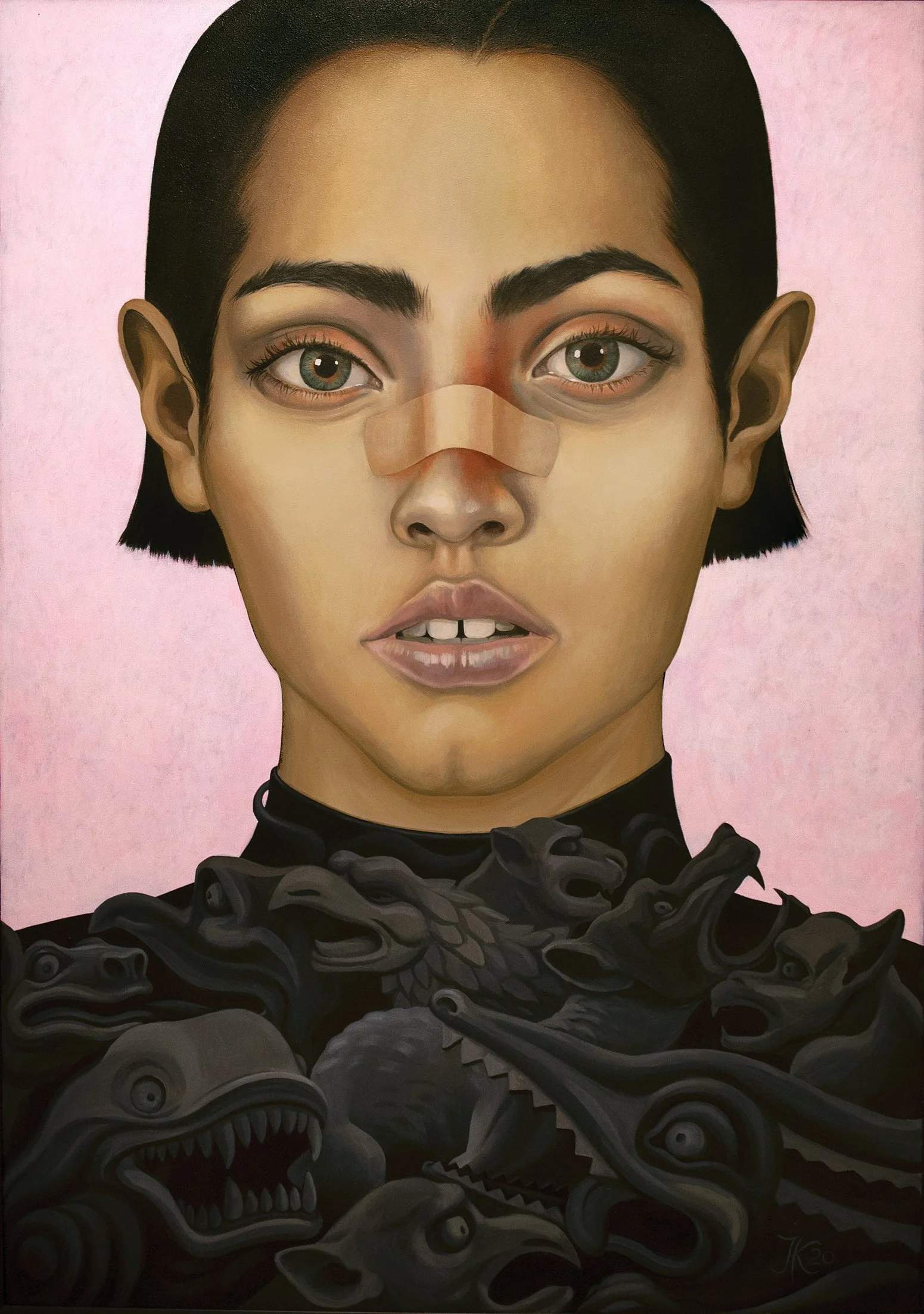

Angela Oil on canvas 36 x 36 inches

Looking forward, do you imagine your work moving toward further reduction or increased narrative density, and how do you envision future audiences situating your paintings within a culture defined by speed, dematerialization, and visual excess?

As an artist, I would consider that moving toward further reduction or increased narrative density in my work would serve to sharpen the emotional or conceptual impact of my paintings. By paring down elements, the work could gain clarity and directness, inviting viewers to engage more deeply with subtle details or themes. Conversely, increasing narrative density would allow for richer, more layered storytelling, encouraging audiences to spend more time unpacking multiple meanings.

In a culture defined by speed, dematerialization, and visual excess, I envision future audiences situating my paintings as a deliberate counterpoint—offering moments of focused reflection amid the relentless flow of digital imagery and information overload. My work could be seen as a space for slowing down, for appreciating the tactile and material qualities of paint, and for reconnecting with narrative depth in a visually saturated world.

Ultimately, my paintings might function both as a refuge and as a provocation, encouraging viewers to reconsider the pace and substance of contemporary visual culture. My work will continue as a visual narrative. I am in my mind allowed to indulge in my paintings and reminding me of different adventures or the people in those adventures. I largely ignore our culture of speed, dematerialization, and visual and other excesses. I play my music and I paint my pictures. I wander around the world……

Maison Sauvage in Paris Oil on canvas 36 x 36 inches