Interview with Jaehee Yoo

https://www.instagram.com/jaeheeyoo78/

Jaehee Yoo, your practice repeatedly frames itself as a diary, yet it resists the confessional in any literal sense. How do you understand the paradox of translating intensely private memory into images that aspire to collective recognition, and where do you locate the moment at which autobiography shifts from personal record to a shared visual language?

For me, the form of the diary is not a means of recording facts or making direct confessions, but a way of quietly returning to emotional traces. My work begins with personal memory, yet I do not seek to illustrate specific events or narratives. Instead, I focus on the sensory and emotional residues that remain. Memory is inherently unstable—it fades, shifts, and reforms over time. I translate this condition into images while preserving ambiguity, allowing them to remain open rather than fixed.

I believe that when an image exists not as a defined story but as an emotional condition, it creates space for viewers to encounter their own experiences within it. This connection does not depend on shared narratives, but on the resonance of emotional and perceptual structures. At a certain moment in the process, the image begins to exist independently of me. Rather than resolving it completely, I step back and leave it open. In this openness, the work moves beyond a personal record and becomes a shared perceptual space—one where memory, emotion, and presence briefly converge, allowing viewers to linger and recognize something of themselves within the image.

Working primarily with Indian ink, silk, and Hanji, you engage materials saturated with historical memory and cultural intimacy. How do these materials function not only as supports but as active agents that shape temporality, vulnerability, and emotional resonance within your work?

Materials such as Indian ink, silk, and Hanji are not merely passive surfaces, but living mediums that carry their own temporality and cultural memory. They contain accumulated histories, and the marks left upon them become layers of time rather than simple gestures. My process is not about imposing an image, but about entering dialogue with the material and its inherent behavior.

Silk and Hanji absorb ink in delicate and unpredictable ways, unfolding between control and chance. Once a trace is made, it cannot be reversed. This irreversibility closely reflects the nature of memory, which is unstable and constantly shifting. The fragile surface of silk holds a quiet tension, while the ink resists settling into fixed forms. Through this instability, I seek to evoke emotional states that exist in transition.

I regard these materials not as tools, but as active participants in the work. By allowing their material flow to guide the image, the process becomes a convergence of time, perception, and matter. Silk, for me, acts as a metaphor for memory. —its organic diffusion and disappearance giving rise to the dreamlike and mysterious atmosphere that defines my work.

The Memory Diaries position Seoul not as a neutral setting but as a lived and remembered organism. How does the city operate in your paintings as a psychological structure, and how do its rhythms, densities, and silences reconfigure your understanding of landscape?

In Memory Diaries, Seoul is not simply a backdrop, but a living organism shaped by accumulated memory and emotional experience. Rather than depicting the city as a physical place, I follow the sensory and emotional traces it leaves within me. My landscapes are not representations of specific locations, but psychological spaces where internal states and external environments intersect.

The rhythm and density of the city—its fleeting light, constant movement, and unexpected moments of stillness—create a tension that deeply influences my perception. I am particularly drawn to the solitude that emerges within crowds, and to the presence of silence within noise. These experiences allow the city to exist not as a fixed image, but as a fluid and shifting condition shaped by time and memory.

In my work, the city remains ambiguous, diffused, and layered, reflecting its nature as something continuously reconstructed through emotional experience. By keeping the image open, I invite viewers to enter the work through their own memories and perceptions. In this way, the city becomes not a defined place, but a shared psychological space.

Line seems to function as both gesture and thought in your work. How do you conceive of line as a cognitive and emotional trace rather than a descriptive tool, and how does it record time, hesitation, and internal pressure within a single movement?

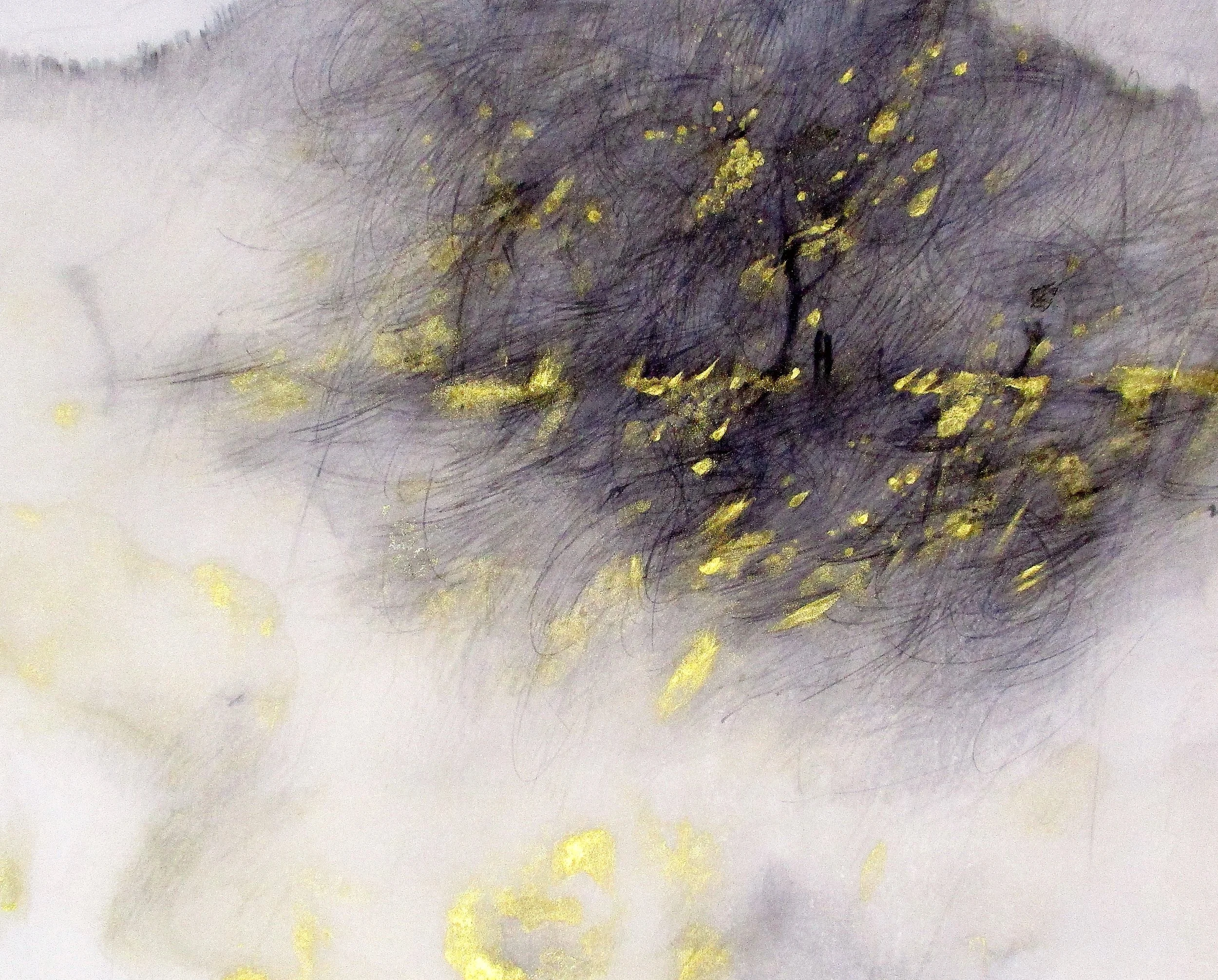

In the tradition of East Asian painting, the line embodies the flow of vital energy and reveals the essence of the artist. My lines encapsulate change and velocity; fine, sharp strands intertwine like hair. In fact, the idea of these tangled lines came to me while washing my hair in the shower. I was struck by the beauty of the movement and silhouette created by long, delicate strands—clusters of lines that felt both sharp and free.

For me, drawing a line is akin to breath meditation. The process of reaching inner stillness closely parallels my creative practice. The tension and shifting emotions generated by short and long breaths condense into images—unspoken states of sorrow, solitude, or even joy. Rather than constructing form through line, I seek to record the places where thought and emotion briefly came to rest.

Your process begins with meditation and an encounter with the blank surface. How does this act of quiet acceptance shape your relationship to control, chance, and authorship, and what does it mean for an image to arrive rather than be planned?

My work begins in meditation. The dialogue with the blank surface is an extension of that meditative state, and within this process I move back and forth between the positions of artist and viewer. I sometimes describe this exchange as a “contact.” The trigger is often simply loosened thread in the silk, a drop of ink fallen by accident, a faint shimmer on the surface. These small incidents become the starting point of the encounter.

Through this contact with the surface, I enter a dialogue with images that emerge—whether by chance or by inevitability—and wait for the moment when a primary image reveals itself. This is the moment when the image “arrives.” I step in as the author of the work, composing a mise-en-scène. Yet I do not conclude the work with an explanatory resolution; instead, I leave space and withdraw. At that moment, the work becomes its own subject, and I return to the position of viewer. I prefer to keep the work open rather than closed.

Many of your recent works focus on lovers, separation, and the impossibility of reunion. How do you approach intimacy as a structural condition rather than a narrative subject, ensuring that emotional proximity remains unresolved rather than illustrative?

For me, intimacy is not defined by narrative, but by a state of psychological tension that exists between two presences. My work focuses on the relational condition of figures, particularly the subtle interval between connection and separation. I am drawn to moments that remain unresolved—where emotional proximity coexists with distance.

The figures in my paintings often face one another without fully meeting, sharing the same space while remaining within their own interior worlds. I seek to capture fragile and emotionally charged moments between lovers—moments of encounter, hesitation, and parting. These moments exist outside of linear storytelling, suspended in a state of emotional tension.

Like a cinematic long take, time in my work appears slowed and extended. I observe from a distance, allowing the emotional atmosphere to unfold without resolution. This openness invites viewers to enter space as witnesses, sensing shifts in emotional presence and imagining what remains unspoken. In this way, intimacy becomes not a fixed event, but an ongoing condition of tension, distance, and emotional resonance.

Figures in your work often appear waiting, gazing, or suspended at thresholds. How do you use erasure, diffusion, and spatial ambiguity to articulate emotional states that exist between presence and disappearance?

The lovers in my work remain at a distance, quietly gazing at one another, suspended in a state of relationship that has not yet reached its conclusion. Because emotions and relationships are never fixed but continuously shifting and open-ended, I leave their narrative unresolved, allowing what comes next to remain unwritten. These moments of mutual regard—poised at the threshold between sorrow and joy, pain and tenderness—form a delicate balance charged with sensory and emotional tension. To sustain this tension, I employ ambiguous diffusion, layered ink washes, and the latent energy of emptiness.

The figures within the image exist in a state of simultaneous emergence and disappearance. Through this ambiguous boundary, I seek to suggest that presence is not a stable or singular entity, but something closer to a fluctuating and unstable sensation—one that is continually forming, dissolving, and transforming.

Your academic training in traditional Korean painting and Oriental art history forms a quiet foundation beneath your contemporary practice. How does historical knowledge operate in your work as an internal logic rather than a visible reference?

At the age of sixteen, encountering a painting of Avalokiteshvara rendered in ink and gold pigment on silk at a Buddhist temple became a pivotal moment for me. That tradition entered my practice not as something learned, but as an internal foundation, something that felt as innate as DNA. The Buddhist philosophies of emptiness, karma, causality, and impermanence function as invisible yet fundamental principles underlying my work. Within this framework, East Asian painting is not an act of representation, but a philosophical practice concerned with rendering underlying principles rather than appearances. The notion of “revealing invisible truth” and the idea of “resemblance through non-resemblance,” articulated in classical Chinese painting theory, have deeply influenced my approach and continue to be actively embodied in my work.

Silk absorbs ink in ways that resist precision and control. How does this material instability parallel your understanding of memory as mutable, fragile, and resistant to fixed representation?

The process of applying ink on silk unfolds within an unstable temporality shaped by chance and continual transformation. The way ink is absorbed is never the same; each mark settles irreversibly, leaving a trace that cannot be undone. The diffusion and permeation that occur on silk closely mirror the temporal nature of memory—how it forms, dissolves, and reconfigures over time.

Rather than fully controlling this material behavior, I allow the image to emerge through the inherent flow of the medium itself. I do not regard this instability as a flaw to be corrected, but as an essential condition that reflects the nature of memory. It is precisely within this unpredictability that the work finds its conceptual and material foundation.

The recurring presence of your cat and moments of domestic intimacy introduce a different scale of attention. How do these intimate motifs function as anchors of reality within works that often hover between abstraction and narrative?

Motifs such as my cat and moments from everyday life are deeply personal to me, yet they also function as the most tangible points of reality. These small presences anchor the sense of “here and now” within the otherwise fluid terrain of abstract emotion and memory, allowing the image to remain in balance without drifting entirely into abstraction or narrative. At the same time, they serve as reminders that memory is rooted in lived experience.

For me, these beings are less symbolic than they are traces of immediate reality—points at which perception and sensation first begin. Without relying on grand narratives, they hold the capacity to convey the density and continuity of lived time. In this way, such motifs play an essential role in my work. They also offer viewers a point of entry, making the work more accessible while inviting deeper emotional and perceptual engagement.

Your urban landscapes oscillate between figuration and abstraction, refusing stable orientation. How do you understand this instability as an ethical strategy that allows viewers to enter the work through their own memories rather than consume a closed image?

My landscapes move along the threshold between figuration and abstraction, inhabiting a space where seemingly disparate elements—past and present, intimacy and distance, tradition and contemporaneity, control and chance—paradoxically converge. Rather than presenting a fixed orientation or predetermined structure, I seek to keep the work open, not as a closed image but as a perceptual field into which the viewer’s own memory and sensibility may enter.

The instability and ambiguity within the image are not intended to obscure meaning, but to create a space of openness—an active interval that invites the viewer’s participation. Within this space, the viewer brings their own memories into the work, encountering the landscape not as something to be definitively interpreted, but as a temporary site where recollection may surface, linger, and quietly unfold.

Golden tones frequently surface in works addressing longing and loss, creating tension between beauty and sorrow. How do you think about this chromatic contradiction as a way of complicating emotional legibility?

Gold began as a color I used to evoke light, and over time it has become a symbolic presence within my work. It has come to embody a state in which beauty and sorrow coexist without resolution. For me, gold also carries the sensation of loss and absence, even as it radiates luminosity. Have you ever experienced the brilliance of May as something that quietly reveals inner sadness? When contradictory emotions remain side by side without being reconciled, the viewer is invited to pause, suspending familiar habits of interpretation.

I believe this moment of perceptual and emotional stillness is where my personal memory begins to resonate with the emotional landscape of others. Light illuminates the surface, yet it also reveals distance and silence. This paradox resists fixing emotion into a single, legible state, allowing multiple and conflicting sensations to remain present at once. Within this ambiguity, I hope beauty and sorrow may be experienced not as opposites, but as inseparable aspects of a shared and enduring emotional condition.

You have spoken about believing that the most subjective experiences can convey the most objective truths. How does this belief challenge dominant notions of universality in contemporary art discourse?

I believe that the most personal experiences have the potential to form the deepest connections with others. When an intensely private experience is confronted with honesty and specificity, the viewer may encounter a sense of resonance—an awareness that, although the story is not their own, something within its emotional structure feels intimately familiar. It is from this point that the Memory Diary series began.

I understand universality not as something neutral or generalized, but as something that emerges from the deepest interior of one’s own experience. My work originates in personal memory and emotion, yet when these elements remain open and are not fixed into a single meaning, viewers are able to project their own experiences into the image. This connection does not occur because a particular narrative is shared, but because the underlying structures of sensation and feeling are often deeply alike. In that moment, the personal image expands into a shared perceptual field—one in which individual memory becomes a space for collective resonance.

As a contemporary Korean painter working with traditional materials, how do you position your practice within modernity without framing tradition as either burden or nostalgia?

My use of traditional materials is not an attempt to reproduce the past, but a choice grounded in a material language that is most intimately connected to my own sensibility. Silk and ink are mediums that reveal the passage of time and the presence of chance, and through their material properties, I experience the process by which images come into being.

For me, tradition is not something I consciously select, but something embedded within my work as an intrinsic part of my identity—almost like DNA. As a contemporary Korean woman artist, the past is not separate from the present, but a way of inhabiting and understanding it. For this reason, I remain cautious of visually reiterating traditional motifs in a purely referential manner. What matters most is always the presence of who I am now. I seek not only to work with the materials and forms of East Asian painting, but also to reinterpret its philosophical and perceptual foundations through the language of contemporary art. I believe that through this ongoing process of tension and translation, my own artistic signature will emerge organically.

Your work often offers viewers a space of quiet recognition rather than spectacle. In a city and world saturated with speed and visual noise, how do you imagine the ethical role of such images, and what responsibility do you feel toward the emotional states they may awaken?

I hope my paintings can become a space in which the viewer may linger—an environment that invites quiet contemplation. Amid the constant circulation and rapid consumption of images, I wish to offer a pause: a space where one can encounter their own emotions, a margin of silence and stillness. I believe that art holds the capacity to open a space for inward breath and the possibility of healing. As an artist, I feel both the responsibility not to impose a singular emotional response and the responsibility to keep the work open.

Rather than delivering a fixed message, my work seeks to create a condition in which viewers may quietly face their own memories and emotions. Within this space, they remain aware of the image while simultaneously becoming aware of themselves. I believe such encounters can create small but meaningful moments of balance. This, for me, is an ethical position—one that does not prescribe or direct emotion but allows it to emerge and be experienced freely.

Lover under Jinko tree 46x53cm painting on silk 2022

Parting 55x44cm Indian ink painting on silk canvas 2024

Missing you 57x44cm Indian ink Drawing on silk canvas 2024

Approaching 54x44cm Indian ink Drawing on silk canvas 2024

Already been a year 50x44cm Indian ink Drawing on silk canvas 2024

Reunion 50x44cm Indian ink Drawing on silk 2024

Cat and I 68 X58cm Drawing on silk 2024

My S Diary_Cat and I 50W X60HcmDrawing on silk 2024

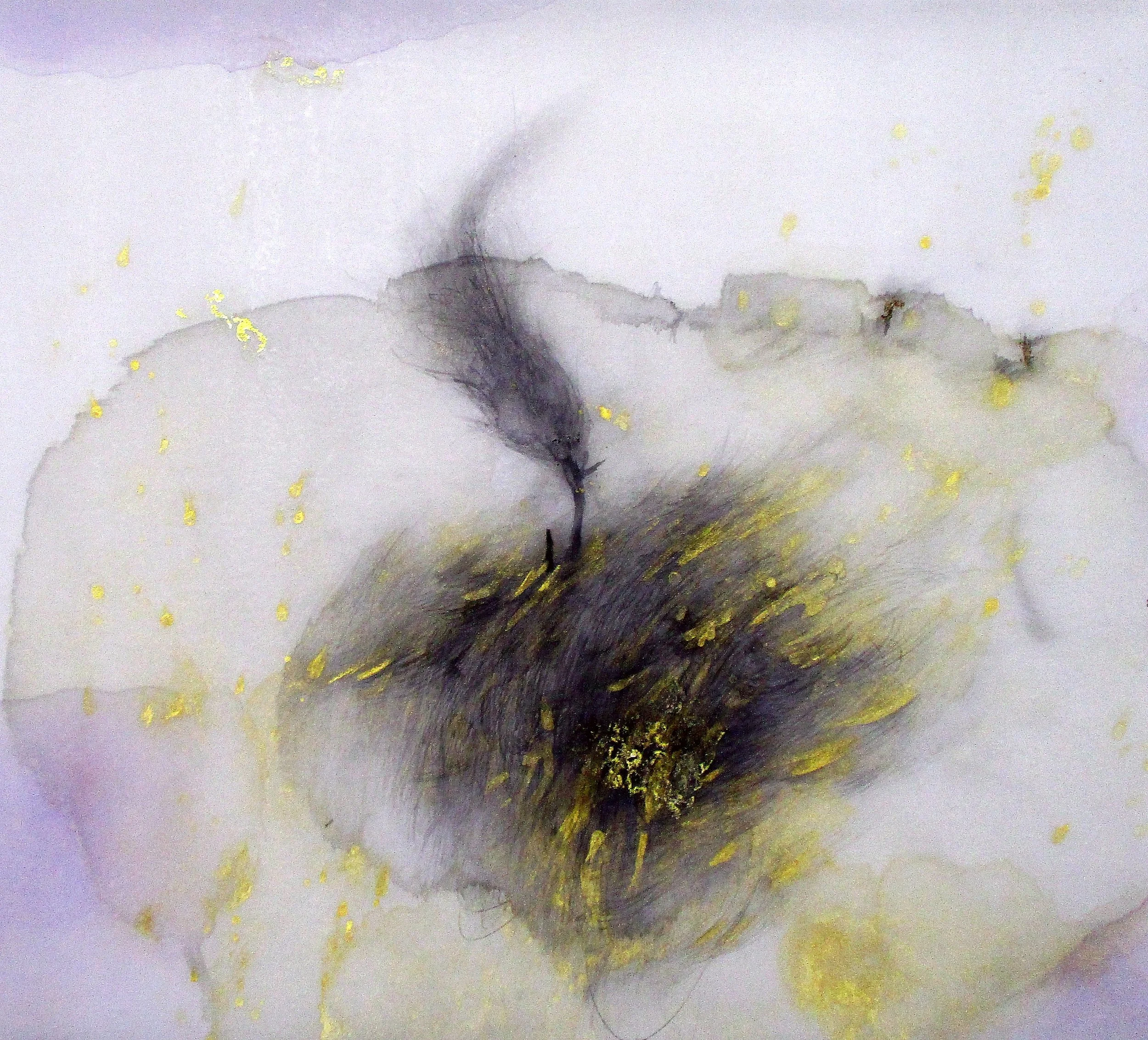

Cherry Blossom Lover 46x53cm Indian ink Drawing on silk 2025

Waiting for you 44x60cm Indian ink Drawing on silk 2025

Shall we dance? 44x60cm Indian ink Drawing on silk 2025

Under the Platanus tree 44x55cm Indian ink Drawing on silk 2025

Nocturne73x61cm Indian ink Drawing on silk 2023

Winter city 68x58cm Indian ink on silk canvas 2025