Hélène Paulette Côté

Hélène Paulette Côté’s recent dimensional paintings begin from a proposition that seems, at first, almost disarmingly simple: a painting is not a window, not a screen, not an image to be consumed at a single frontal point, but an event that happens between a body, a surface, and the light that binds them. Yet in Côté’s hands that proposition is not a slogan, and certainly not a nostalgic return to some pre-digital aura. It is a precise, materially argued critique of the way contemporary vision has been trained to behave. The works insist, with quiet authority, that seeing is never neutral. Seeing is choreographed. Seeing is historically produced. And in a moment when the world is increasingly negotiated through flat interfaces and instantaneous scroll, Côté makes paintings that refuse to stay flat, refuse to stay obedient, refuse to behave like images at all.

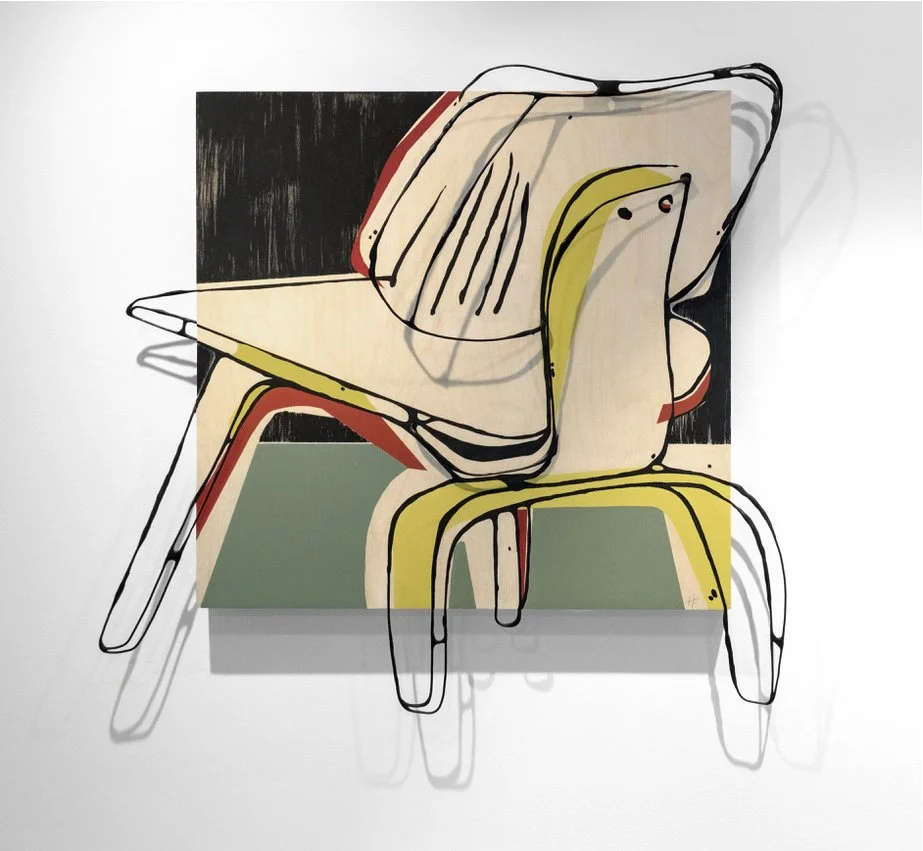

Her dimensional paintings, executed in acrylic on wood panel and extended with dowels, wire, and constructed elements, occupy an unusual and compelling threshold. They do not seek the theatricality of sculpture, nor do they accept the pictorial self-containment that modern painting once claimed as its purity. Instead, they operate as hybrids that interrogate the boundary itself, the seam where pictorial sign becomes object, where a line stops being depiction and begins to cast a shadow, where color ceases to be only optical and becomes environmental. This is not simply painting plus add-ons. It is painting rethought as a spatial grammar, a syntax that includes the wall, the room, and the viewer’s movement as active components.

Côté’s biography matters here not as ornament, but as a kind of structural key. Born in Montréal into a family of painters, with a mother and grandmother who worked in the medium, she inherits painting as a lived practice, a domestic continuity, an embodied knowledge. That lineage is important because it complicates the modernist fiction of painting as a solitary invention, made ex nihilo by heroic rupture. In Côté’s case, painting is also memory, transmission, a way of learning how attention is sustained across generations. At the same time, her trajectory moves decisively outward, through cities that each represent different economies of vision: Montréal and Paris, New York and San Francisco, Los Angeles and Dallas, Toronto and Vancouver, and now the East Bay of California. In each place, the artist absorbs the codes by which images circulate, persuade, seduce, and command. She learned English early, not as a simple linguistic acquisition but as a shift in cultural optics, a second set of idioms through which the world names itself. To live between languages is to become acutely aware that meaning is not inherent in forms, it is produced in relation.

Her early career as a silkscreen artist and printmaker sharpened this awareness. Silkscreen is a medium of edges, of registration, of separation. It teaches the discipline of the stencil and the inevitability of layering. It insists that an image is constructed through decisions about what is held back and what is allowed through. Côté’s later prominence in printmaking communities, including her role as a founding member of the Manhattan Graphics Center and her leadership within the California Society of Printmakers, indicates how deeply this logic shaped her sense of what an artwork is: not only an object but a practice embedded in collective infrastructures, studios, boards, and communities of making. Printmaking is social by nature. It is technique shared, labor repeated, knowledge circulated. Even when Côté turns toward the singularity of the painted panel, she carries that social understanding with her, and it becomes, paradoxically, a source of formal rigor. The stencil remains, the flat color remains, the hard edge remains, but now they are pressed into a new problem: what happens when the printmaker’s logic of surface is asked to confront depth?

Côté’s decades in graphic design and advertising intensify that problem in another register. Advertising is a field that treats attention as currency and composition as persuasion. It demands clarity, impact, and immediate legibility, even when it pretends to be subtle. Côté’s achievements in that world, including recognition at the level of Emmy and Cannes Lions, are not incidental to her art. They indicate a mastery of visual structure, a command of how shapes pull the eye, how contrast organizes hierarchy, how a single accent can reprogram an entire field. But the ethical stakes are different in art. In the gallery, composition is not required to sell a product. It is required to disclose its own conditions, to reveal the mechanisms by which it works. Côté’s dimensional paintings can be read as a profound conversion of design intelligence into critical form. She takes the tools that were once employed to direct desire outward, toward consumption, and turns them inward, toward perception itself.

The phrase “think outside the box,” so familiar as a corporate mantra, becomes, in her practice, something more literal and more philosophical. The “box” is the panel, the frame, the expectation that an image stays within its boundaries. Côté thinks outside it by forcing the painting to exceed its own support. Yet the gesture is never merely decorative. The extension is always a structural statement: the painting’s edge is not a limit, but a site of pressure. When wire loops drift beyond the panel, when dowels puncture the pictorial field and project into space, when wooden elements protrude and catch light, the work stages the collapse of an old modern distinction between the internal space of the picture and the external space of the viewer. It is here that Côté’s work finds its philosophical depth. The paintings ask, insistently, what counts as inside and what counts as outside, not only in pictorial terms but in cultural ones. Where does an image end, and where does the world begin? In an era saturated with images that behave as if they are the world, that question becomes urgent.

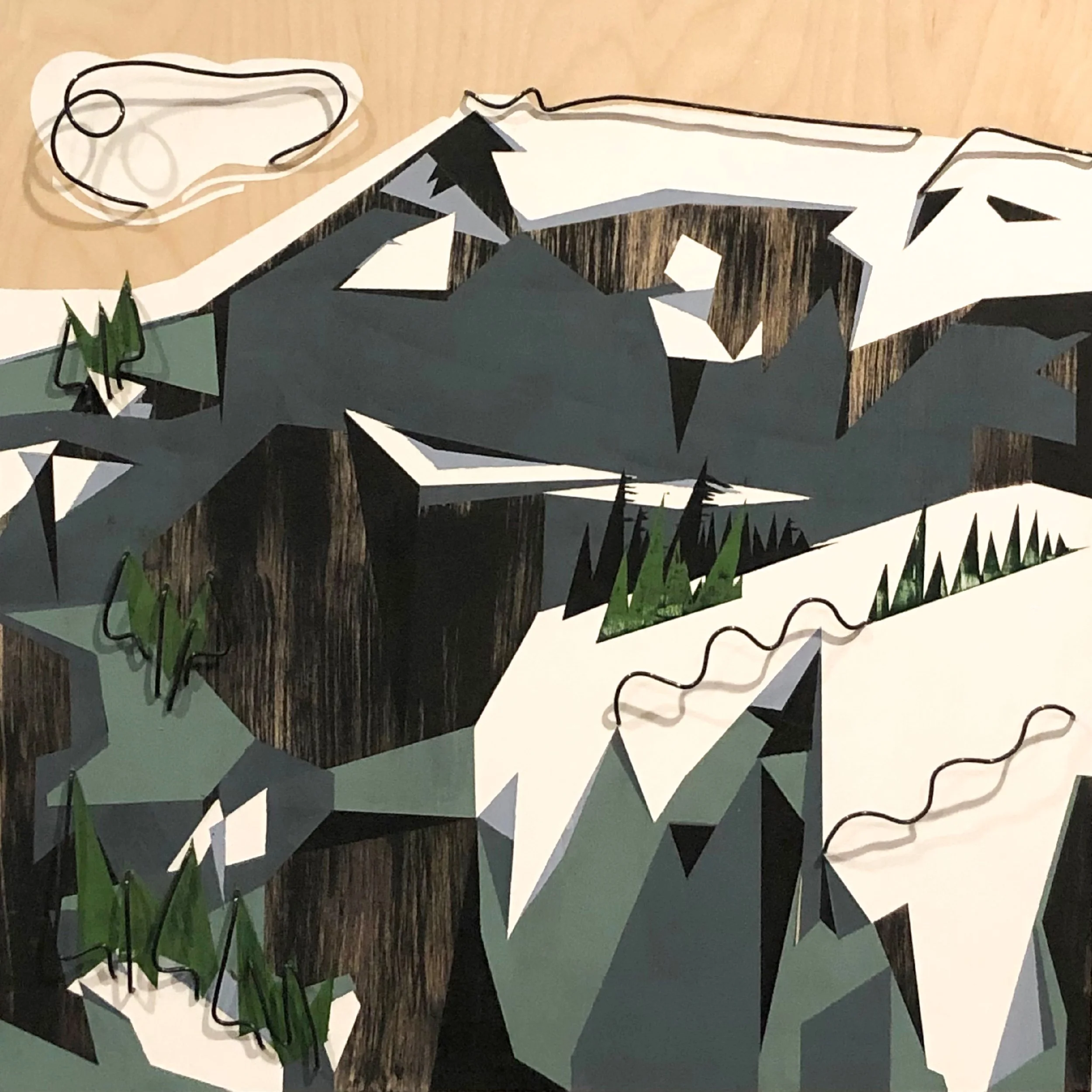

Consider the landscape inflected works, where Côté’s vocabulary of flat shapes and constructed line meets the memory of terrain. In “Mount Judah” (2021), the panel becomes a stage for angular planes of slate gray, deep blue, and snowy white, interspersed with visible wood grain that reads almost like geological strata. The mountain is not described through atmospheric illusion; it is built through facets, as if the landscape were a collage of decisions. Small triangular greens suggest trees, but their stylization keeps them in the realm of sign rather than naturalistic depiction. Above, a wire line loops into the space like a drawn cloud that has refused to stay on paper. Its shadow, cast on the pale ground, becomes an additional line, a second drawing made by light. The work thus splits mark making into two agencies: the artist’s hand and the environment’s illumination. One draws in wire, the other draws in shadow. The result is a landscape that is also a diagram of perception, a reminder that what we see as “nature” is always mediated by the conditions of viewing.

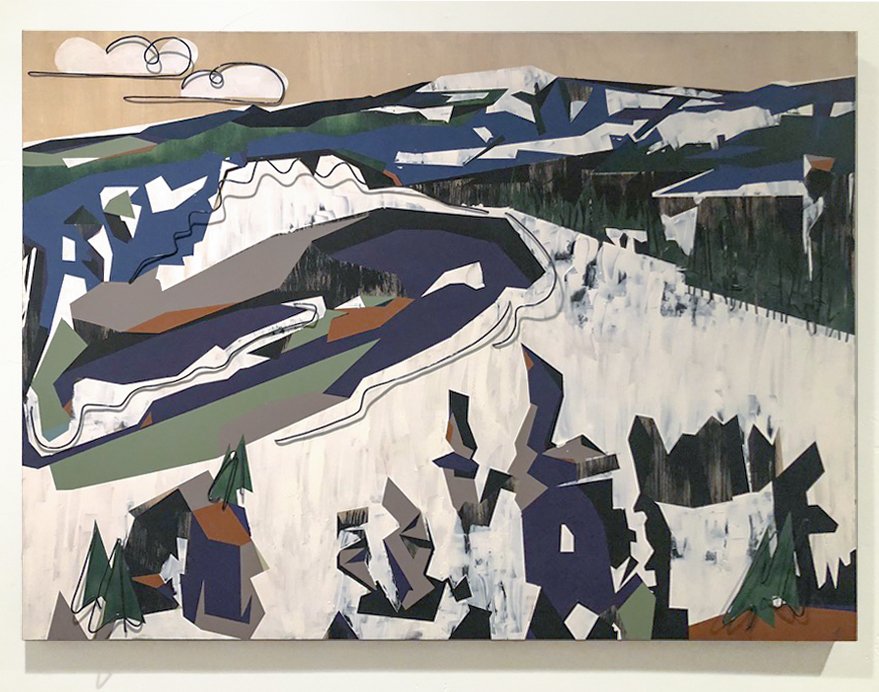

“Spring Thaw” (2021) amplifies this principle into a more expansive field. The composition reads as a sweeping topography, but its articulation is resolutely graphic: broad areas of white suggest melting snow, while deep blues and greens stack into ridges and distant mountains. The pictorial space is simultaneously deep and flat, an oscillation that recalls modernism’s refusal of stable illusion. Yet Côté complicates the modernist flatness by introducing wire elements that hover at the surface and then step forward into real space. The wire cloud at the upper left, delicately looping, sits like a punctuation mark in the sky, but it also announces the painting’s refusal to be only an image. The thaw, then, is not only seasonal. It is conceptual. The work thaws the rigid separation between depiction and construction, between landscape as motif and painting as object.

It would be easy to locate these works within a lineage of geometric abstraction that flirted with landscape, from the synthetic cubist fragmentation of form to the later hard edge painters who translated horizon and ridge into bands and angles. But Côté’s landscapes are not exercises in style. They are propositions about how contemporary subjectivity is situated. The mountains are not romantic refuges. They are structures, systems, built from the same visual logic that builds the city, the screen, the interface. In this sense, Côté’s landscapes are contemporary precisely because they treat nature as something already coded, already designed, already encountered through maps, signage, and mediated travel. The mountain becomes a field where the politics of representation and the poetics of place collide.

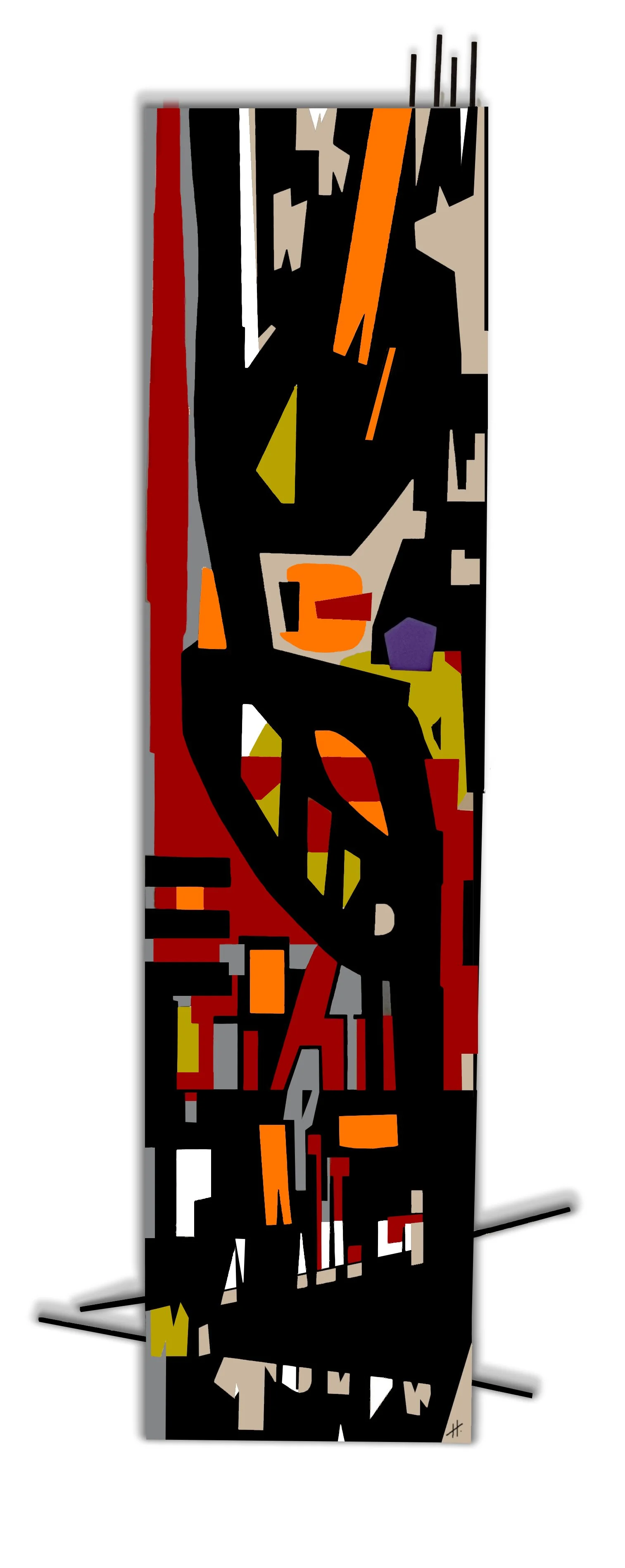

The more overtly urban and architectonic works push this collision further. “City Garden” (2022), a tall narrow panel, reads like a compressed metropolis, a vertical stacking of black forms, red bands, and bright accents of orange, yellow, and muted neutrals. The composition has the urgency of signage, the density of a city seen through peripheral vision. Yet it also includes protruding elements that break the silhouette and declare the work’s physicality. These extensions, like small interruptions, are not simply sculptural embellishments. They function as spatial syntax, as if the city itself were pushing outward, invading the viewer’s space. The title “City Garden” suggests a paradox, the desire for organic refuge within constructed density. Côté’s work does not resolve the paradox; it makes it perceptible. The garden is not painted as foliage, it is registered as a rhythmic opening, an interval within the urban grid. The painting becomes a meditation on coexistence, on how the organic and the manufactured interpenetrate, and on how the body navigates that interpenetration.

If the landscape works stage the meeting of terrain and diagram, and the urban works stage the compression of sign and structure, the more abstract pieces reveal the core of Côté’s practice: an exploration of how form behaves when it is forced to become spatial. “Round & Round” (2024) unfolds across a wide panel like a dynamic circuit. Large black shapes, arcs and blocks, lock into fields of gray blue, cream, yellow, and red. Circular motifs appear, not as stable centers but as rotational forces, suggesting repetition, recurrence, a kind of visual time. A wire line near the central seam functions like a hinge, a drawn thought that cannot quite settle. In the upper right, a circular form reads simultaneously as a target, a record, a loop. The painting’s logic is not narrative in the literary sense, but it is temporal. It insists that looking is not instantaneous. The viewer’s eye must travel, return, reorient. The title becomes a description of perception itself: round and round, not because the painting is confusing, but because it is structured to produce sustained engagement, to resist the quick consumption that contemporary images solicit.

“Incursion” (2024) is more austere, and in that austerity it clarifies Côté’s philosophical ambition. Large areas of black flank exposed wood, with slender vertical intervals that read like slits of light or architectural voids. The wood is not hidden; it is allowed to speak as material, as grain, as warmth against the black’s absorptive depth. Small protrusions at the top edge suggest an intrusion into space, a literal incursion beyond the boundary. Here the drama is minimal but intense. The painting becomes a study of threshold, of what it means for an image to be breached. The incursion is not violent; it is conceptual. It is the moment when a flat surface admits that it is not self sufficient, that it belongs to a world of objects and shadows.

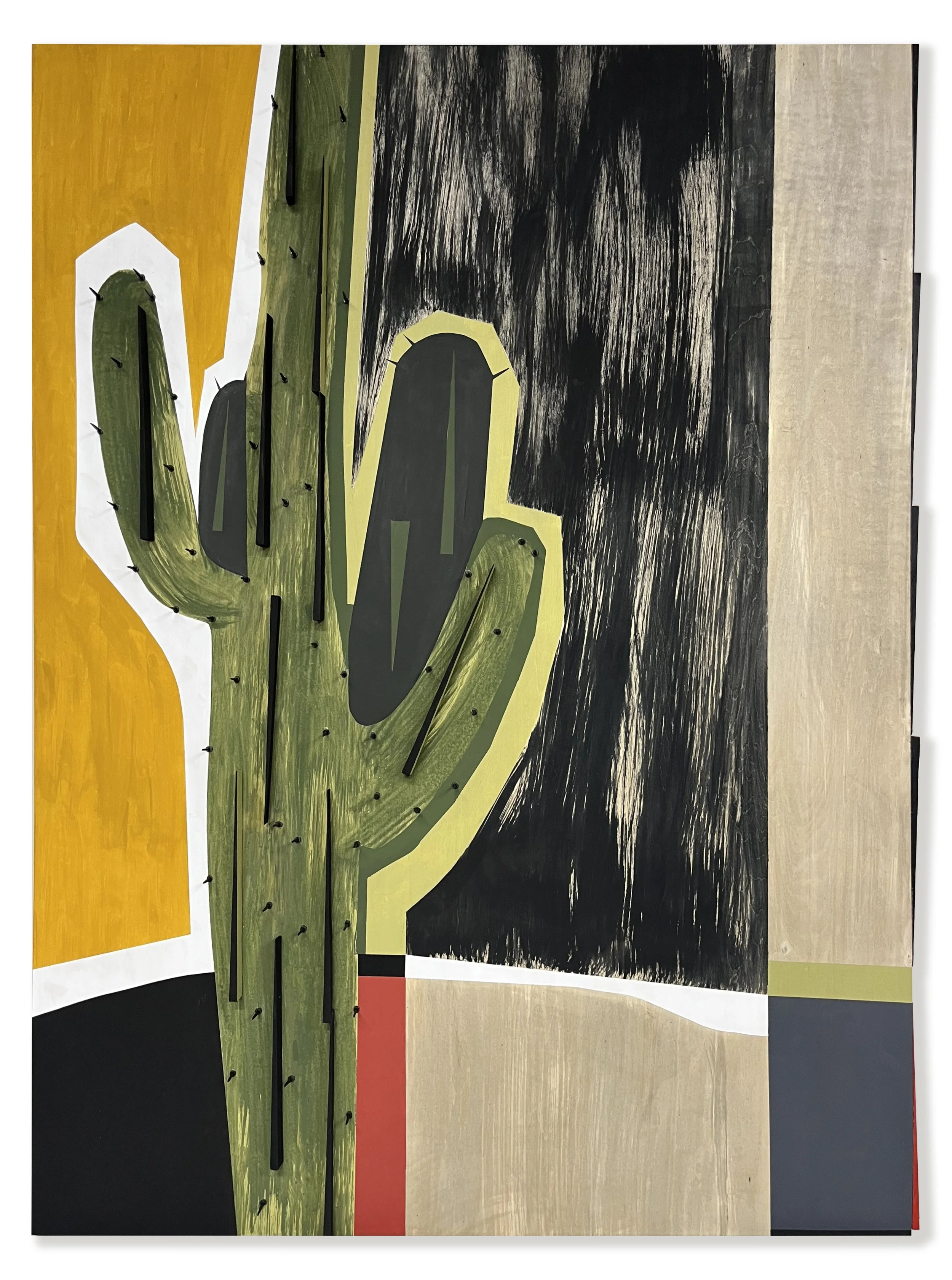

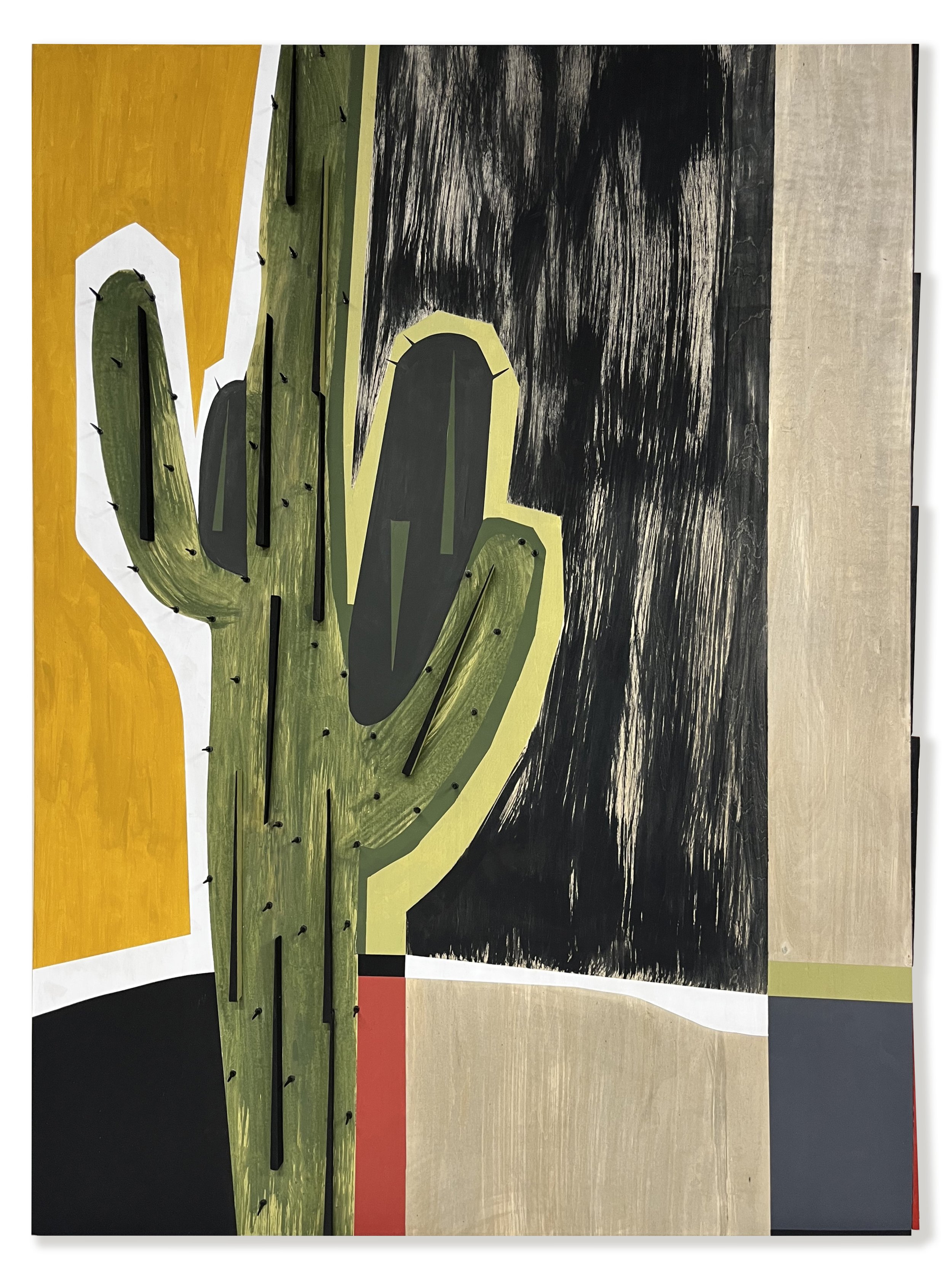

In “Saguaro” (2024), the motif returns, but the treatment is radically contemporary. The cactus is rendered as a stylized form, green against fields of ochre and black and neutral tones. Yet the cactus is punctuated by raised elements, spikes that appear as both literal protrusions and as signs of defense. The saguaro, a plant that survives through adaptation, becomes an emblem of resilience, but also of the way organisms exist within harsh environments. In a time of ecological stress, the cactus can be read as a figure for endurance, for the capacity to persist without romanticizing suffering. Côté’s cactus is not sentimental. It is structural. It is built, like her other forms, from a grammar of edges and planes. The work thus suggests that resilience is not a mythic trait but a constructed relationship to environment, to scarcity, to time.

The horizontal piece “I Call It Fish” (2025) demonstrates how Côté’s titles often function as invitations rather than declarations. The composition is dominated by a deep black field interrupted by red arcs, a pale wedge, and a small yellow form that reads like a signal or a buoy. On one side, thin elements extend outward like whiskers or antennae. On another, a cluster of small protrusions punctuates a pale area, producing a tactile rhythm. The “fish” is not an illustrated creature; it is a perceptual possibility. The painting offers a set of cues and allows the viewer’s imagination to complete the association. This is crucial. Côté’s work does not impose iconography. It activates it. It treats representation as something that emerges in the viewer’s mind as a response to form. In doing so, it relocates meaning from the object alone to the interaction between object and observer. The fish is not in the panel; it is in the relational space of looking.

“ModPod” (2025) intensifies the sense of a constructed visual environment. Large black shapes press against muted blues and grays, while red and orange accents strike through like architectural supports or emergency signals. A wire loop extends at the upper right, a line that refuses to be contained. On the left edge, thin rods project outward, as if the painting were testing the air around it. The center is punctured by vertical flecks of light, pale bars that evoke windows, code, or the fragmentary illumination of a city at night. The work feels both composed and alive, as though the geometry were under pressure from some internal pulse. It is here that Côté’s background in design becomes most visible, but also most transformed. The work has the clarity of a designed field, but it uses that clarity to produce uncertainty, to ask what these structures are for, what they hold, what they exclude.

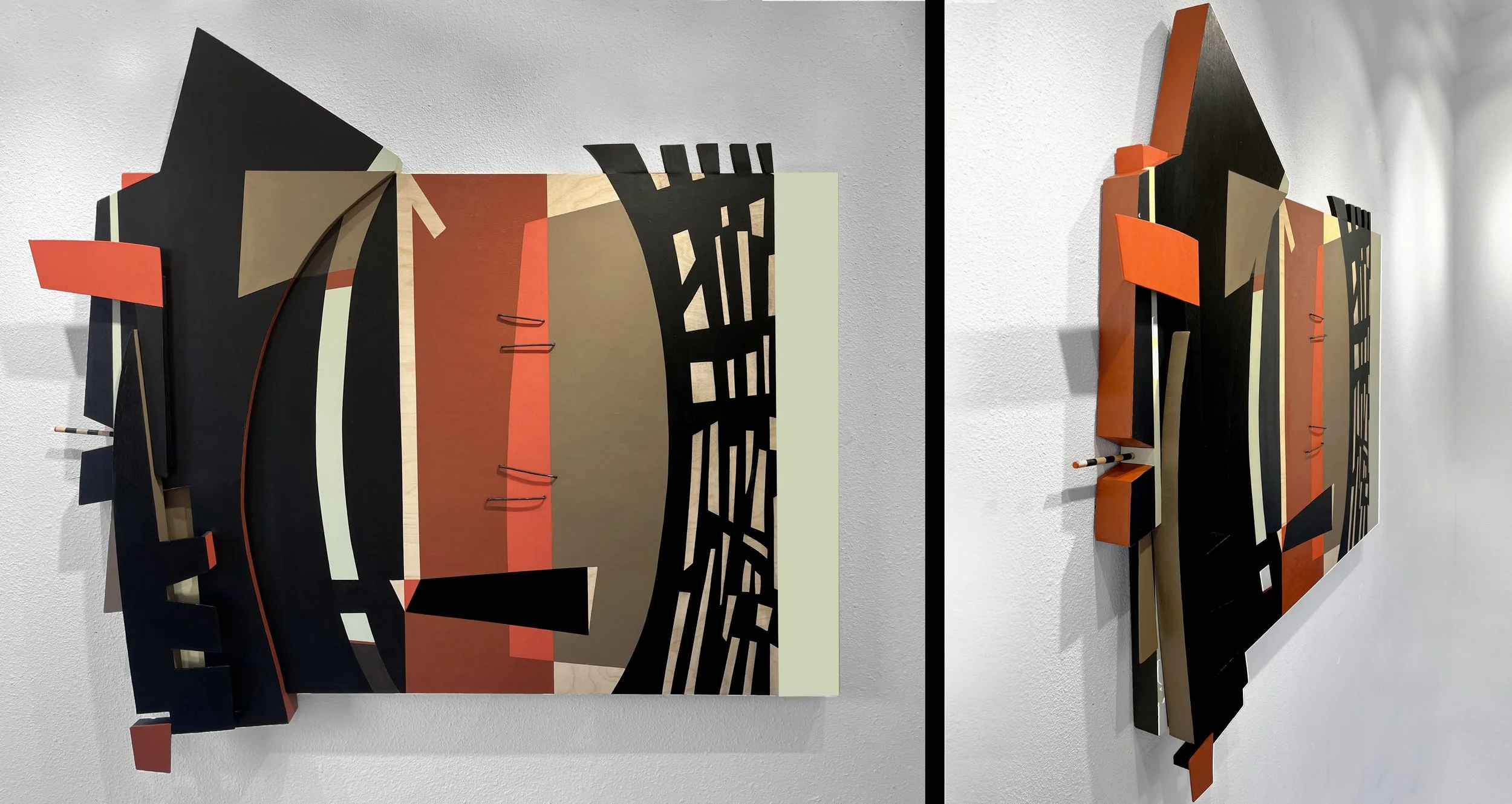

“Groove” (2025) offers perhaps the most explicit declaration that Côté’s paintings are also objects. The work projects from the wall with layered components, creating a relief that is both sculptural and pictorial. The palette, with black, warm neutrals, creams, and vivid orange, produces a sense of rhythm and syncopation. The protruding forms cast shadows that change as the light shifts, and those shadows become part of the composition. The painting grooves, not only as a metaphor for rhythm but as a literal channeling of space. The work makes the wall an active participant, because the wall receives the shadows, holds them, and thus becomes a secondary support. In this sense, Côté’s dimensional paintings propose a dispersed authorship. The artist constructs the object, but light composes the shadow, and the viewer’s movement edits the relation between them.

It is tempting to describe these works through the familiar language of crossing disciplines, painting becoming sculpture, relief painting, expanded field. But the real significance lies less in hybridity as a category and more in what Côté’s work reveals about medium as a cultural contract. A medium is not only a set of materials. It is a set of expectations. Painting is expected to be frontal, stable, bounded. Sculpture is expected to be volumetric, navigable, occupying shared space. Côté disrupts these expectations not to prove that she can, but to expose the arbitrariness of the boundaries themselves. In doing so, she returns the viewer to a more fundamental question: what does an artwork demand of the body?

Her answer is clear. The work demands that the body move, that the viewer become aware of their own position, that perception be understood as temporal and contingent. This is where her practice becomes socially important. Contemporary life trains bodies to sit still while images move. Screens scroll; the viewer remains fixed. Côté reverses this. The image resists scrolling. It requires locomotion. It asks for a kind of attention that is increasingly rare, an attention that is not merely cognitive but embodied. To stand before one of her works is to realize that the artwork is not finished until the viewer has navigated it. Shadows appear and disappear. Wire lines double themselves through their cast forms. Painted shapes change their dominance depending on angle. The work is thus a quiet pedagogy of attention. It teaches seeing as an active practice.

There is also, in Côté’s work, a profound meditation on the ethics of influence. Her use of hard edged color and modular form resonates with histories of abstraction, with the reduction of form to geometry that marked early twentieth century experiments, and with later movements that emphasized the literal objecthood of the artwork. Yet she does not reenact these histories as style. Instead, she reframes their stakes for a present in which abstraction has been absorbed into everyday visual culture. The modernist dream of pure form has long since been commodified, turned into branding, interior design, and digital interface. Côté, coming from advertising itself, understands this with unusual clarity. Her paintings therefore operate as a recovery mission. They take the language of modern design and return it to the realm of inquiry, where form is not simply pleasing but consequential.

This is especially evident in her handling of color. The palette is often bold, but never gratuitous. Black functions as a mass, a gravitational field that holds other colors in tension. Reds and oranges appear as strikes, as moments of urgency. Creams and exposed wood offer breath, intervals of warmth and material truth. In certain works, the wood grain becomes a kind of memory trace, a reminder that beneath the designed surface there is a natural substrate that refuses complete control. Color, in Côté’s hands, is not only optical sensation. It is structure. It is the distribution of forces across a field.

Her line, too, is distinctive. Often rendered in black, sometimes in wire, it behaves less like contour and more like a record of decision. It is gestural without being expressionist. It is energetic without being chaotic. This balance can be traced to her printmaking background, where line can be drawn directly onto a screen with oil pastel and translated through resist into printed form. That history lingers in the way her lines feel both immediate and mediated, both spontaneous and disciplined. When the line becomes wire, it crosses a threshold from representation to presence. It becomes something the body can measure. It casts a shadow that becomes a second line, and the two lines create a conversation between touch and light, between the made and the given.

It is also important to situate Côté within the contemporary art scene not as an isolated figure but as an artist deeply embedded in communities of practice. Her studio base within a multidisciplinary space in Emeryville places her within the East Bay’s long tradition of artist run culture and material experimentation. Her affiliations with institutions such as KALA and her service on boards reflect a commitment to sustaining the infrastructures that allow art to exist beyond market spectacle. At the same time, her selection as one of ten women in the Jen Tough 2025 Collective, with visibility at major fairs and presentations including the Los Angeles art fair circuit and an upcoming presence at the 2026 Los Angeles Art Show, indicates that her work is also entering broader cultural circulation. This matters because her paintings are not merely formal achievements; they propose a different mode of spectatorship, one that deserves wide encounter.

To write about the cultural stakes of Côté’s practice is to recognize how her work addresses a core anxiety of the present: the fear that experience is becoming increasingly abstracted from the body. The digital world offers endless images, but it also threatens to reduce the world to images. Côté’s dimensional paintings resist that reduction by insisting on thickness, on shadow, on the untranslatable specificity of real space. They remind viewers that perception is not an upload. It is a negotiation with gravity and light. In that sense, her work has philosophical affinity with traditions that insist on the primacy of embodied experience, even as it remains rigorously abstract. The paintings do not illustrate philosophy. They enact it.

There is, finally, an optimism in Côté’s work that is neither naïve nor decorative. It is an optimism rooted in the belief that perception can be retrained, that attention can be reclaimed, that the viewer can become an active participant rather than a passive consumer. When Côté writes of making the viewer part of the work, she is not offering an interactive gimmick. She is articulating a serious ethic of relation. The artwork is not a closed object that the viewer decodes from a distance. It is a partnership between artist, object, environment, and audience. As light changes, the work changes. As the viewer moves, the work changes. In other words, meaning is not fixed. It is produced in time.

This is why her dimensional paintings feel so necessary now. They do not simply add dimension as a novelty. They use dimension to expose how meaning is always dimensional, how it always exceeds the surface of what is seen. Côté’s practice offers a model for what contemporary abstraction can be when it refuses both the nostalgia of purity and the cynicism of design as mere commodity. She demonstrates that hard edged form can still carry depth, that geometric clarity can still produce mystery, that a painting can be rigorous and generous at once.

The most notable quality of Côté’s dimensional paintings may be the way they convert a lifetime of visual experience, from Montréal’s inherited painterly lineage to Parisian exhibition history, from Manhattan print studios to the advertising world’s sharpened compositional intelligence, into a language that is unmistakably her own. The works carry the imprint of a maker who understands the power of images and therefore refuses to let that power remain unexamined. They are paintings that step forward, literally and conceptually, into the space where viewers stand. They do not ask to be looked at. They ask to be encountered. They restore to abstraction its oldest promise, not the promise of escape from the world, but the promise of re entering it with sharpened eyes and a more responsible attention.

In this sense, the work’s ambition is neither to illustrate an idea nor to declare a position from a distance, but to produce a condition in which the viewer recognizes how perception is made. The dimensional elements do not merely decorate the perimeter of the panel. They establish a field of consequences. A wire loop becomes a line and then becomes a shadow. A protruding wooden form becomes a color block and then becomes an obstruction, a small architectural fact that reorients the body. The paintings therefore operate as propositions about agency: not the agency of the artist alone, but the distributed agency of materials, light, wall, and viewer, each acting upon the other in real time. What emerges is a kind of visual ethics, a reminder that attention is not a passive reception but a responsibility, an agreement to stay with complexity long enough for it to unfold.

To encounter Côté’s dimensional paintings is to feel how the artwork refuses the quickness of contemporary image culture without resorting to nostalgia. The rigor of her hard-edged forms, the disciplined clarity of her color, and the insistence of her constructed extensions make a persuasive case for abstraction as a civic language, one capable of training new habits of seeing. Her contribution to the contemporary field lies precisely here: she restores to geometry its capacity for lived experience, and to painting its ability to be a site of encounter rather than a mere surface of display. In that restoration, the work offers something rare: a renewed confidence that looking can still be transformative.

By Marta Puig

Editor Contemporary Art Curator Magazine

2025. "Groove" acrylic on wood panel with dimensional elements in wood.

2025. "ModPod" 40"Wx30" Acrylic on wood panel with dimensional elements in wire.

2025. "I Call It Fish" Acrylic on panel with dimensional elements in wood and wire.

2024. "Round & Round" 48"Wx24"H Acrylic on wood panel with dimensional elements in wood and wire

2024. "Saguaro" 30"Wx40"H Acrylic on wood panel with dimensional elements in wood and iron.

2024. "Incursion" 30"Wx12"H Acrylic on wood panel with dimensional elements in wood.

2022 "City Garden" 12"Wx36"H Acrylic on wood with dimensional elements in wood.

2021 "Mount Judah" 24"wx24"H Acrylic on wood panel with diemnsioanl elements in wire.

2021 "Spring Thaw" 48"Wx46'H Acrylic on wood panel with dimensional elements in wire.

2020 "Eames Wired" 24"Wx24"H Acrylic on wood panel with wire extensions.