Interview with Brenda Hartill

Born in London, England, Brenda Hartill emigrated to New Zealand with her parents in the late 1950’s, and was educated there, graduating FA honours at the Elam School of Fine Art Auckland. She returned to London in the late 1960’s to study at the Central School of Art and Design, specialising in Theatrical Design. After a period in academic America, she then worked as a freelance designer in UK theatre, including the West End, National Theatre, and Birmingham Rep. In the early eighties, she turned towards printmaking and has successfully published her own prints since. She is a member of the Royal Society of Painter Printmakers

Awards publications and teaching

1965 New Zealand Arts Council award to the Central School of Art and Design.

1971 UK Arts Council award for young theatre designers, to the Young Vic Theatre.

2004 Wrote “Collagraphs and Mixed Media Printmaking”, published by AC Black.

2012 Produced with Klaw Productions, “A Sculptural approach to Printmaking”, an instructional DVD (2 discs 3 ½ hours) – 1990-2012 Teaching Print workshops in etching and collagraph at her studios in Spain, London and Sussex

Exhibitions

Bankside gallery London solo 2014, Curwen & New Academy Galleries, Windmill Street, London (11 solo shows 2013 - 1991,) Saffron Gallery, Battle (solo 2012), Cambridge Contemporary Art, (Sept 2011,2008) St Georges Chapel, Windsor(solo 2009), Hastings Arts Forum, (solo 2009), Roche Gallery, Rye (solo 2023, 2008), Attic Gallery, Swansea, (solo 2020, 2009, 2007,1997, 1994); Lane Gallery Auckland, NZ (solo 2007, 2004) + many mixed shows

Artist’s statement

My work is experimental, abstract and embossed. Collagraph, etching, watercolour, collage and encaustic works. My main love is abstracting the essence of the landscape in richly coloured textured works, often enhanced with silver and gold leaf. Recent works include a series of watercolour paintings with collagraph embossings. My early experience as a theatrical designer has led to a sculptural approach to printmaking, and I have developed a method of inking using the different levels of the plate, mixing primary colours on the matrix, thus producing a shimmer of colour, much as lighting a stage set. My work develops though the materials I use. My current on-going fascination is with erosion, weather patterns, natural textures, growth formations and universal organic forms.

Timeline, solo exhibition Bankside Gallery London 2014

Brenda with her assistant and printer Nicola Jackson

Brenda, your practice repeatedly frames making as a “dance between chance and control,” yet the technical disciplines you deploy in etching, collagraph, carborundum, and monoprint are also systems of regulation, pressure, chemistry, and calibrated risk; how do you theorize the moment when process stops being merely a method and becomes a form of thought in its own right, and what does it mean for you when the plate, the paper, the press, or the pigment begins to behave as a collaborator rather than an obedient instrument?

I have always worked on the edges of control, allowing accidents to happen, enjoying the way in which the various mediums dictate the direction of thought. I play a dangerous game between clarity of thought and allowing accident to dictate. There is a definite collaboration between the firm deliberate aim of the structure and the journey into embellishment, while keeping overall control. I like the balance between the no-nonsense imagery of collagraph, along with the strength and three-dimensional aspects of carborundum, and the delicate tracery of etching and natural plant tracery.

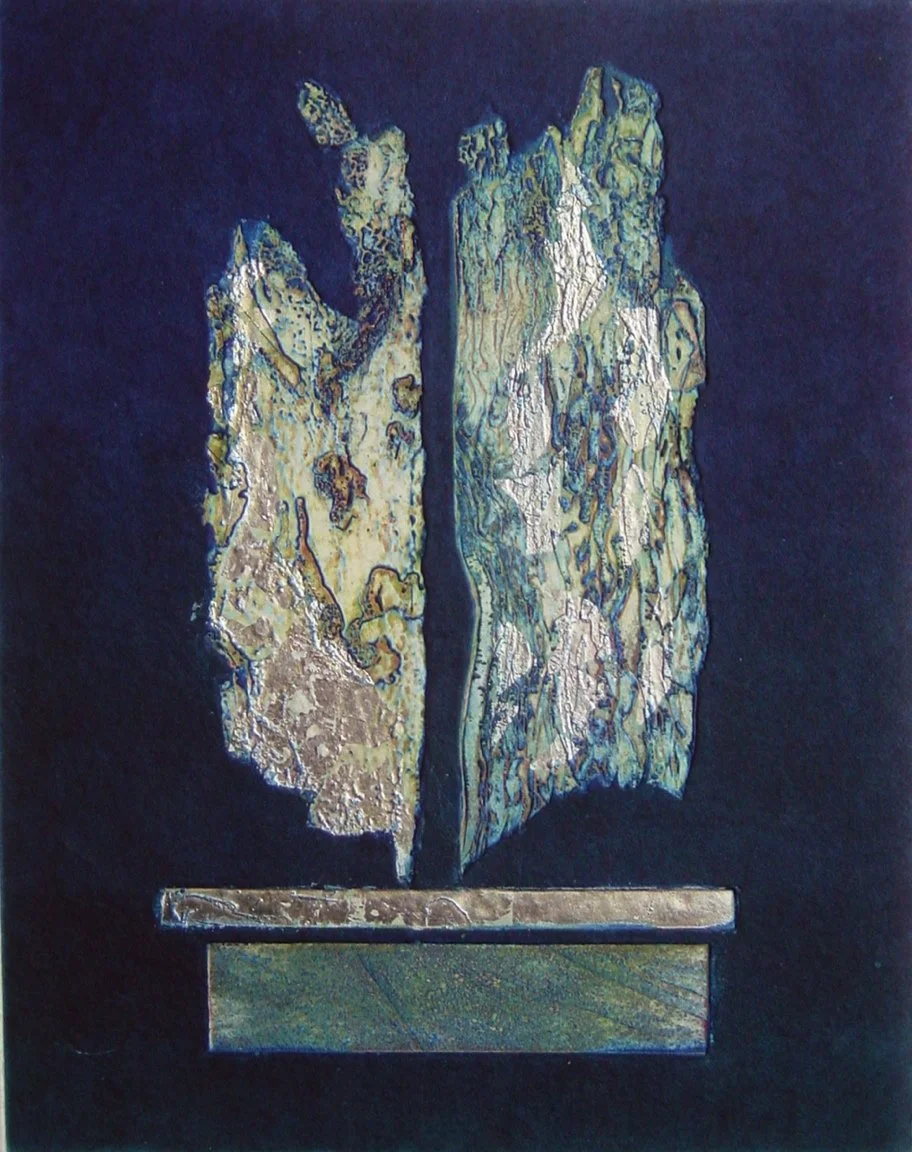

Silver Meltdown I collaged etching with carborundum and silver leaf, img 50x40cm, pap72x56cm

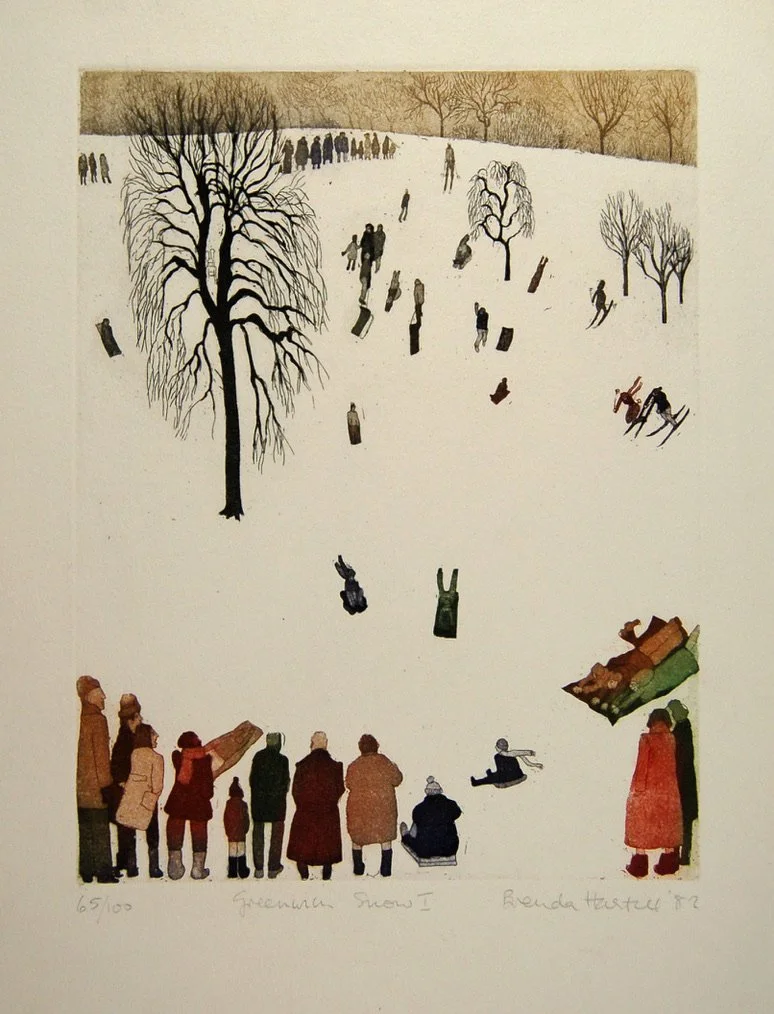

Greenwich Snow etching/aquatint paper 38x28cm, image 20x14cm

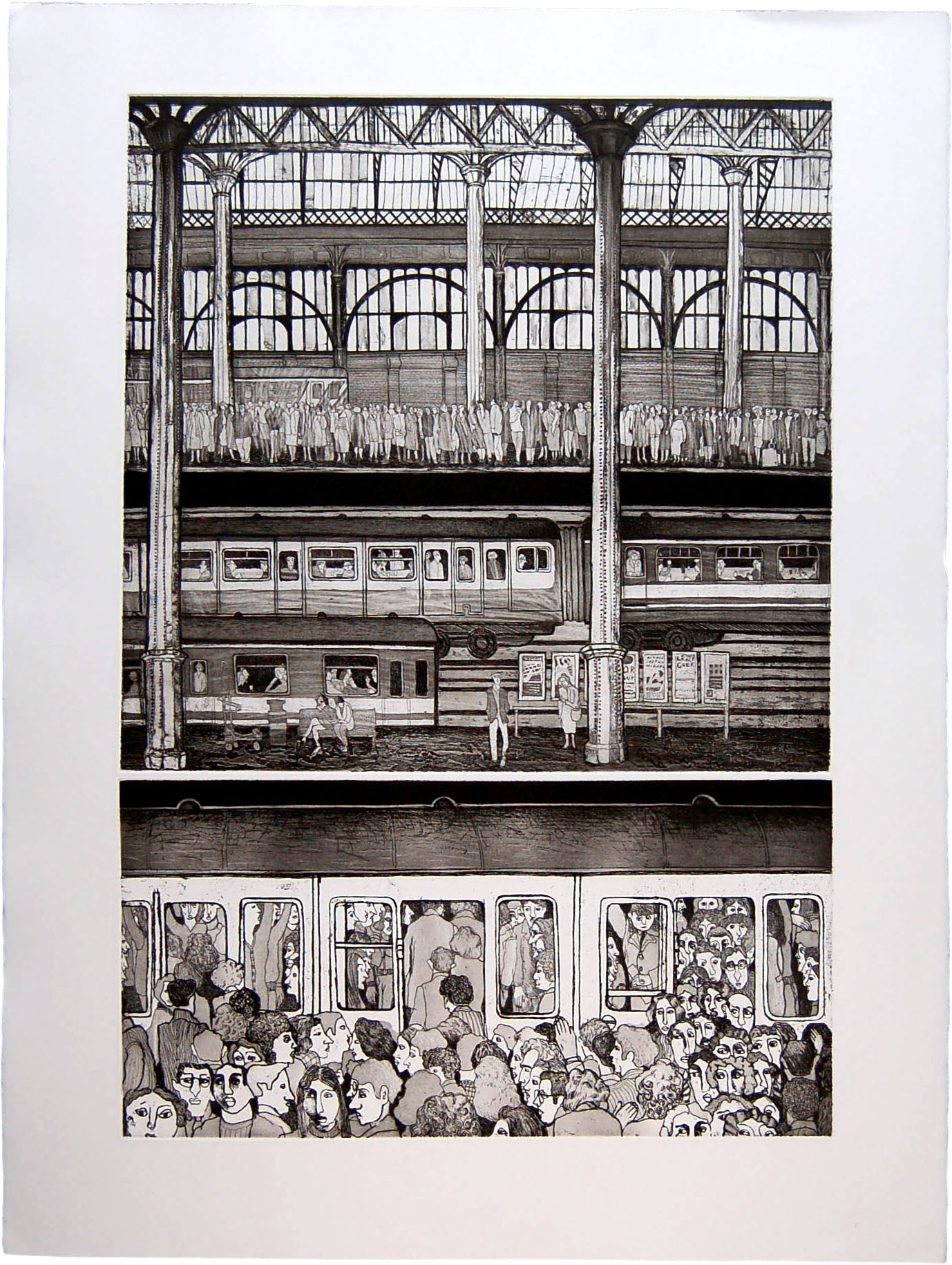

Trainscape IV Waterloo etching img 60x40cm pap 76x56cm

In collagraph especially, you work with found and assembled materials that are then forced through the press into luminous relief; how do you negotiate the boundary between image and object in these works, and to what extent do you want the viewer to register the print as a record of contact and pressure, a sculptural event on paper, rather than as a window onto a depicted world?

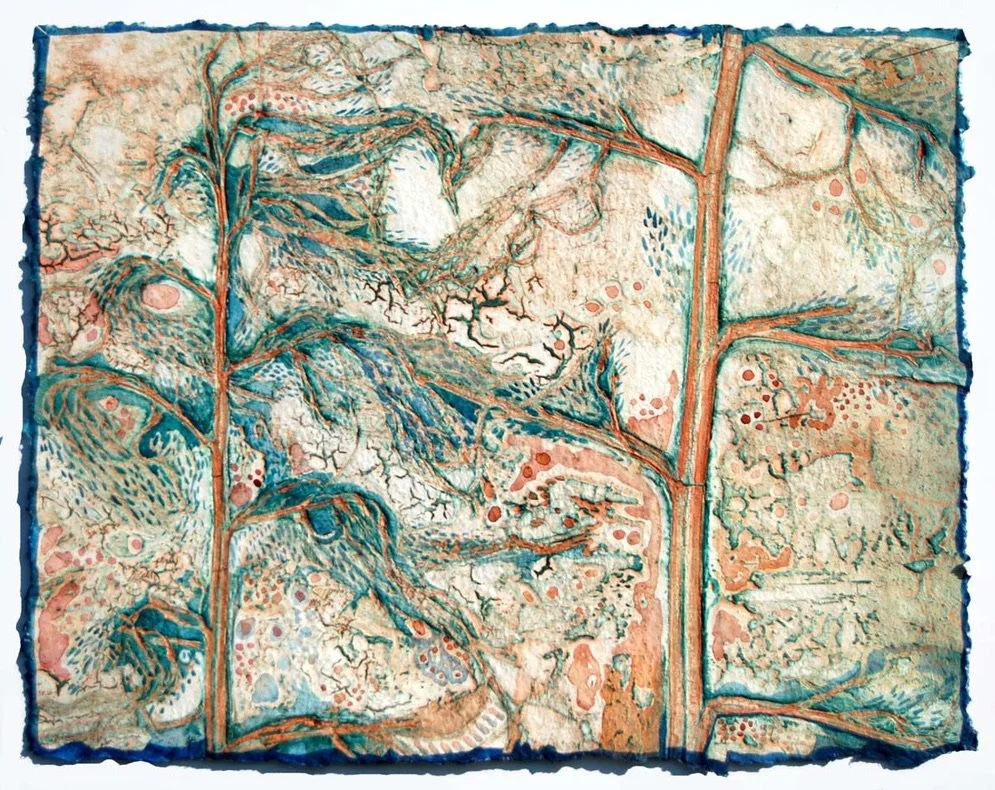

Enchanted Forest III collagraph using plant material and watercolour paper 56x76cm

I want to encourage the viewer to view familiar objects and textures in an unfamiliar way, emphasising the richness of texture and form of quite ordinary objects when working together with disparate forms. I became hooked on embossing and discovered a wonderful heavy-weight hand-made French paper which enabled me to pursue this direction. I became aware of many universal forms: growth structure in plants, trees, animals and humans.

Your frequent resistance to “spelling out” imagery suggests a deliberate ethics of ambiguity, where titles become difficult and meaning is offered as an invitation rather than an instruction; how do you think about authorship in this context, and what responsibilities, freedoms, or risks do you associate with allowing the viewer’s perceptual and emotional projections to complete the work without being anchored by explicit narrative?

Inferno I c pap66x56cm,img.49x46cm

One can only point the way and hope that the viewer “gets” it. When a viewer looks at an art work the artist wants to lead the way to a different perception.

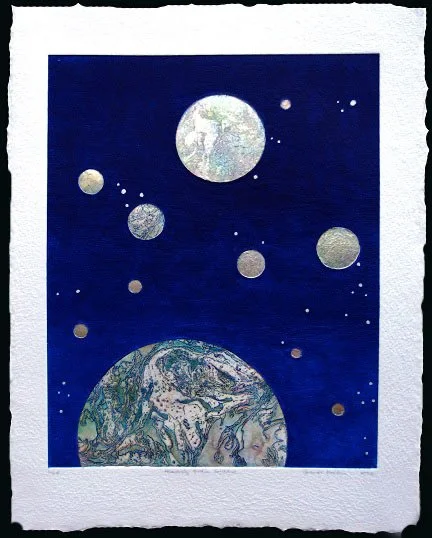

Heavenly Bodies Earthrise, pap 99x71cm, img76x56cm

The theatre had a great impression on my way of thinking and the use of time to enhance changing light and movement of the person. My use of metallic leaf helps to “catch the light” while someone passes by the image, and natural light versus evening light can change an image if it is composed to capture these changes.

Your use of primary colour, overlays, and “free drawing” in monoprint can feel like a direct transcription of energy, yet it is held within an architecture of texture and tonal negotiation; how do you understand the relationship between gesture and structure in these works, and what does the monoprint allow you to say, conceptually and emotionally, that the slower deliberations of etched or collaged plate building might inhibit?

Blue Man cigarette unique monoprint 56x76cm

Monoprint is a very direct process, and unlike my complex built-up etching and collagraph images, it allows pure direct drawing to prevail. When I combine a simple one-colour monoprint to develop with multiple layers, I am enjoying the simple layering process to come through.

The press in your practice is not only a tool but a threshold, a site where force produces meaning through indentation, emboss, and the physical memory of touch; how do you interpret the sensory politics of tactility in printmaking, especially in a culture that often privileges optical consumption, and what do you hope happens when viewers encounter your work as something that seems to ask for an embodied, almost haptic form of looking?

Warm Land I embossed watercolour image uf 61x77cm , fr 91x105cm

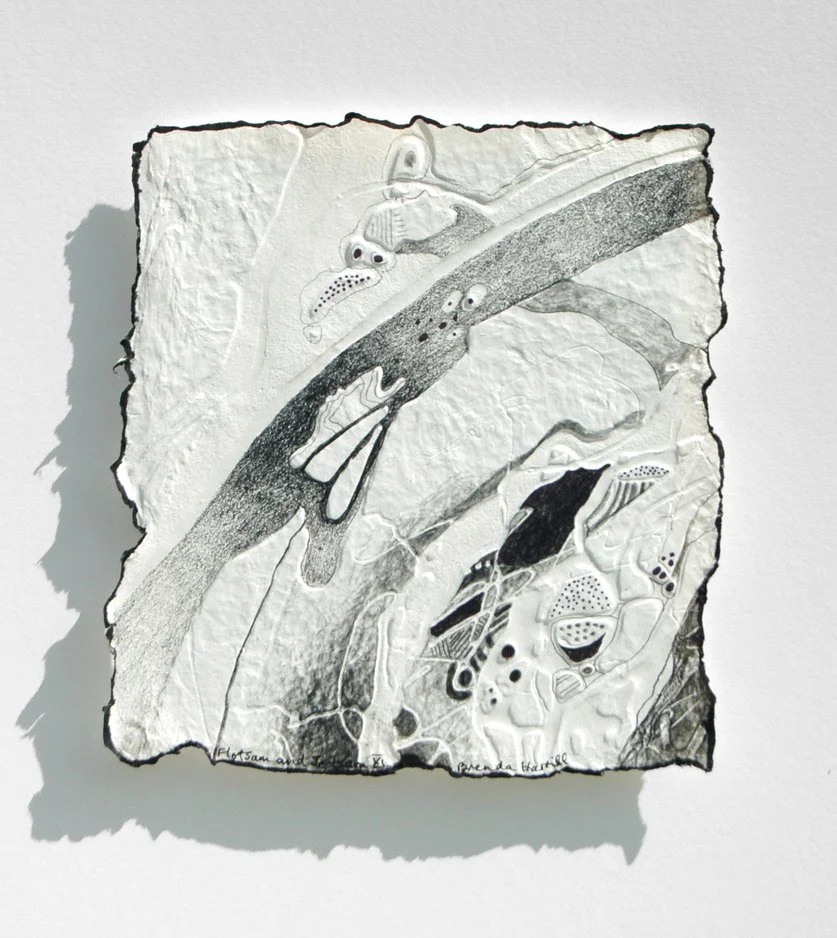

Flotsam and Jetsam XI embossed drawing, img25x23cm, framed 45x43cm

Embossing became increasingly interesting, particularly “blind” embossing, when the shadows cast on the open areas of paper became the most important part of the image. Later when I became interested in embellishing the textures with watercolour, coloured pencils and guilding wax, I was able to create a richness of texture and colour in my use of mixed-media.

You have spoken about working from drawings and photos not as sources for reproduction but as triggers for feeling and re interpretation; could you unpack the cognitive passage from encounter to recollection to abstraction, and how you decide what must be preserved as an “essence” and what must be sacrificed, distorted, or re composed in order for the work to become more truthful to perception than description ever could?

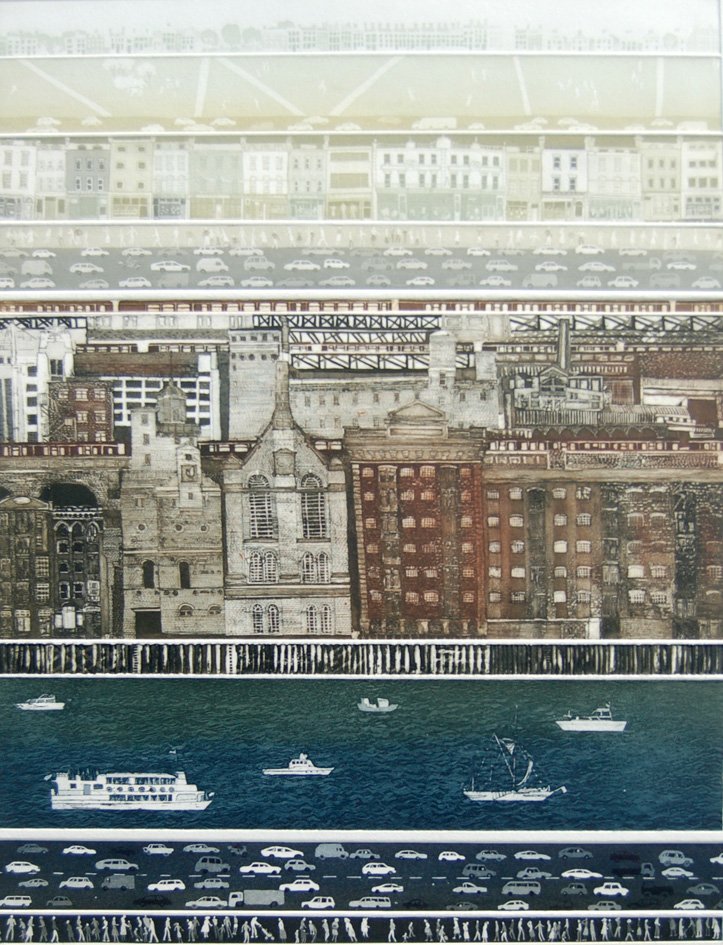

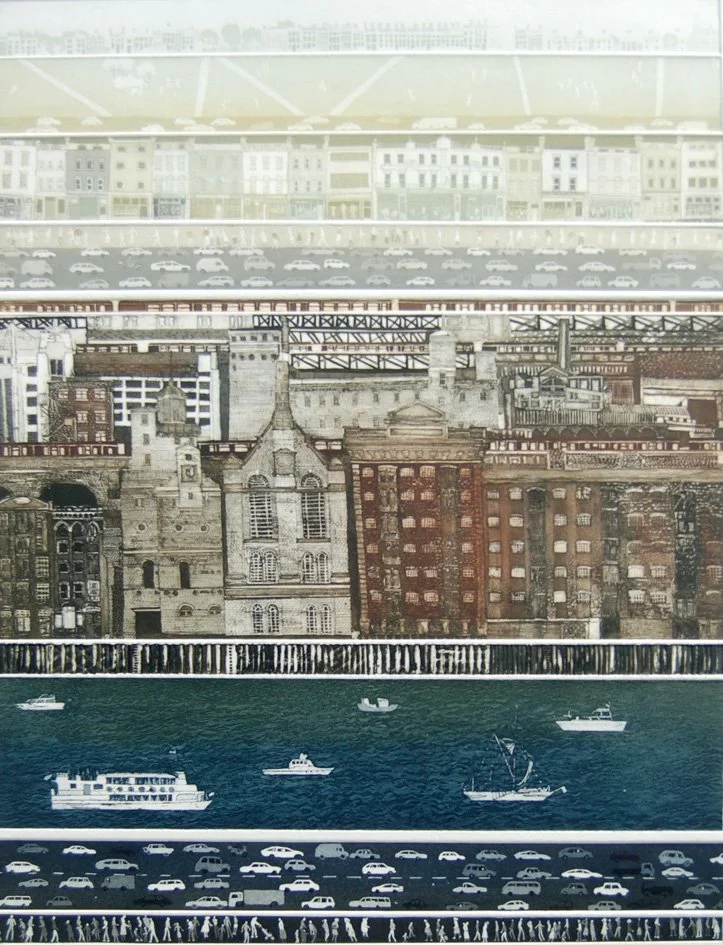

Cityscape I collaged etching, image 80x60cm

I don’t use photography in my preparation, but when I was working on my earlier representational pieces, I would use drawings from nature and the urban environment, sometimes reduced in size to make an interesting composition. My “Londoners London” series was built up from numerous front-on drawings on the spot, to create the houses, bridges, trains, and distant landscapes. I also found that working on separate plates, compiling the composition as I went along gave me the freedom to use different metals, sometimes leaving them in the acid to destruction.

Your incorporation of silver and gold leaf introduces not only brilliance but a historical resonance, calling up icons, devotional surfaces, precious objects, and the long cultural association between luminosity and value; how do you position these materials within your own conceptual field so they do not simply decorate, and what tensions do you cultivate between the metaphysical charge of the metallic surface and the grounded, weathered, geological sensibility of your landscapes?

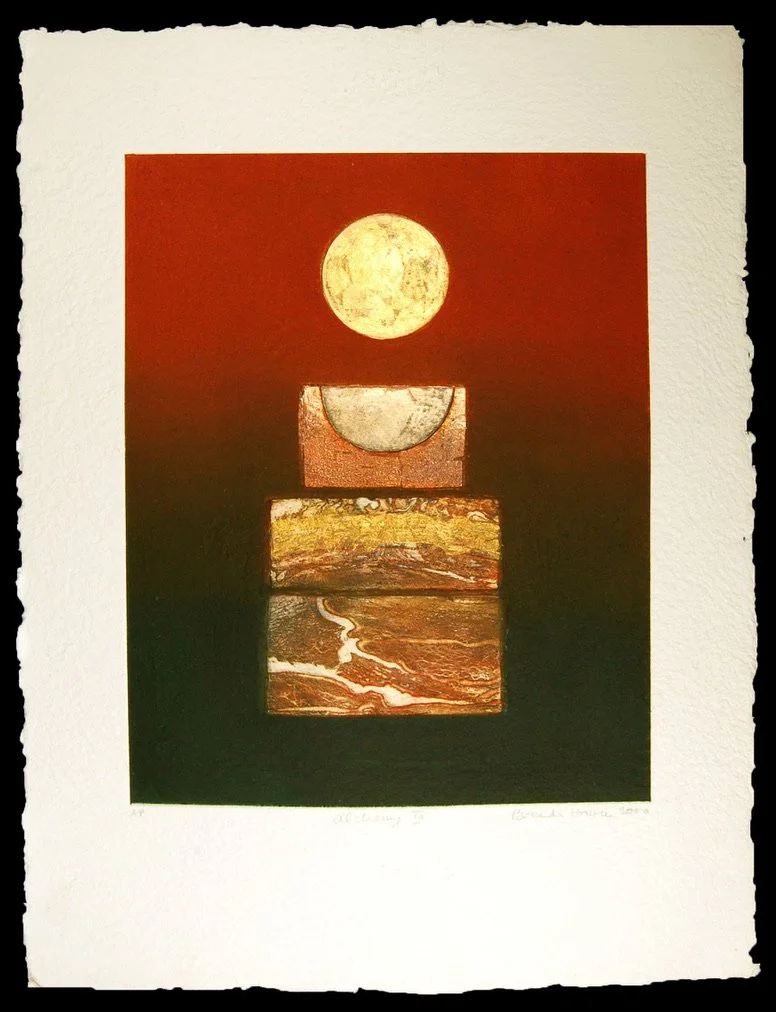

HARTILL Alchemy III collaged etching with gold leaf pap76x56cm, img 50x40cm

The use of gold, silver and copper leaf, as well as guilding wax, has enabled me to add light and richness to the image. However, when working with weathered natural growth forms I tend to stay away from the metallic shiny approach, preferring to find my shapes and textures without that embellishment.

Many of your methods rely on collage logic, whether through collaged plates, switching and recombining elements, or building a “bank” of forms and textures that can be re deployed; how do you think about repetition and return as a creative strategy, and what distinguishes, for you, a productive revisitation that deepens meaning from a repetition that risks becoming a stylistic signature detached from genuine discovery?

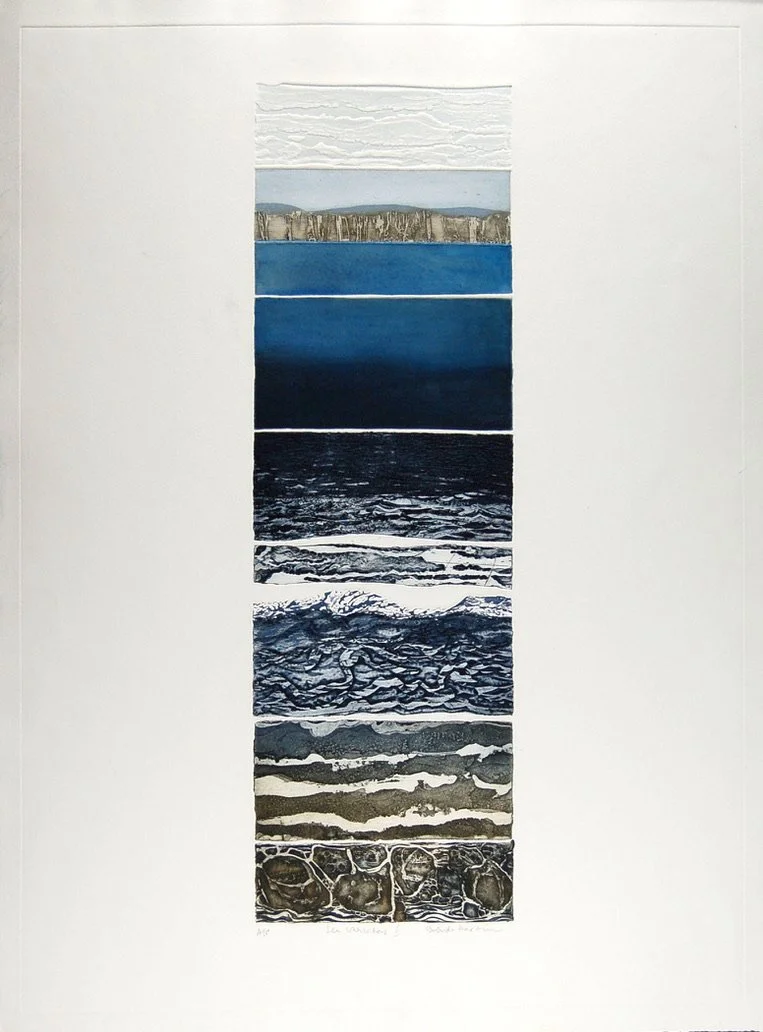

Sea Variations II, collaged etching pap 76x54cm img 60x21cm

I have always been an experimenter, breaking the rules, and using lateral thinking to create my images. I enjoy playing with universal forms; in a series, inking up the same plates in different ways, thus cloud shapes become water, a rocky landscape becomes snowy one, or rivers become roots.

The notion of “viewing landscape from above” and your stated dislike of obvious perspective suggests a refusal of certain pictorial conventions and perhaps of certain cultural positions of mastery; how do you reflect on vantage point as a philosophical problem in your work, and in what ways do your flattened, compressed, or aerial constructions propose an alternative relationship to place, one less about ownership of a view and more about immersion in pattern, structure, and interdependence?

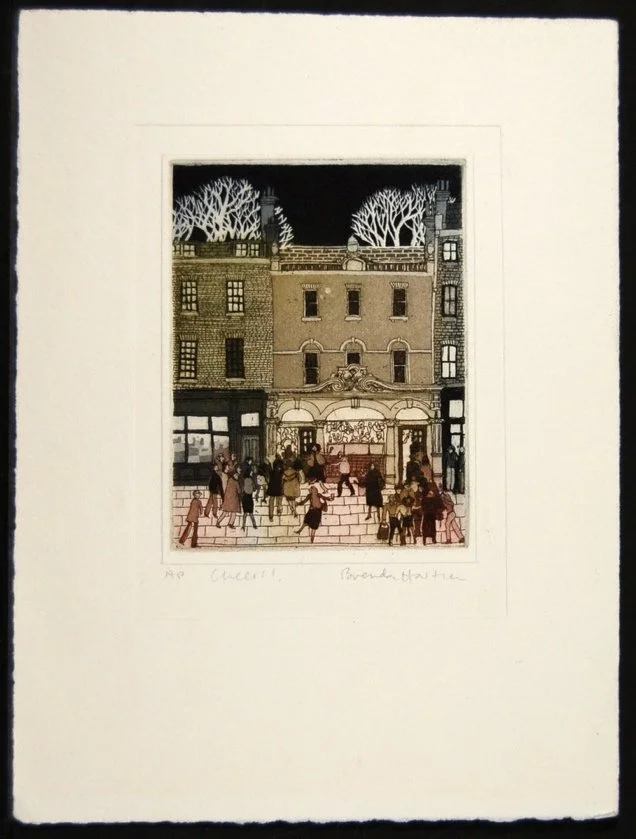

Cheers pap28x20cm img 12x10cm

Perspective and the use of a vanishing point would stop me from treating my landscape in a fluid and flexible way. My bank of works in the “Londoners’ London” series was my way of seeing these images from the point of view of a child, growing up in London.

Your practice repeatedly draws on organic growth forms that echo bodily structures, nerves, muscles, branching systems, and entangled undergrowth; when these correspondences appear, do you think of them as metaphor, as structural analogy, or as evidence of a deeper continuity between human and non human organization, and how might this continuity complicate the boundary between “landscape” and “portrait” within your abstraction?

Spring Song V img 40x56cm pap 56x75cm

I have always felt that growth and erosion patterns are universal: The flow of a river bed, branches of a tree, structure of human and animal bodies, cloud formations, the erosion and breakdown of minerals in rocks and the landscape.

In the later phases of a long career, you describe a period of reflection and enhancement, where physical constraints can change studio possibilities while the imaginative field remains expansive; how has aging altered your relationship to scale, labour, and risk, and what new conceptual freedoms have emerged from working through collage, re invention, and mixed media in ways that re frame earlier printmaking as both material resource and personal archive?

Summer I embossed watercolour, img 57x77cm, fr 81x101cm

Now in my 80s I have sold my heavy-weight Rochat press and have moved from my large oast-house, garden and studio in Sussex, to a Victorian cottage in South London. Downsizing was a painful process, and many of my paintings and prints sadly burnt on the bonfire, with only the best still with me when I moved in just before Christmas 2025. I am about to embark on a period of consolidation, developing my collage and mixed-media works, as well as hopefully embarking on a series of still-life oil paintings (my great love in my early days as an artist). Mobility and health are an issue, as well as the current shocking Trumpian challenge to democracy.

Looking across your trajectory, experimentation seems less like a stylistic preference than a lifelong discipline of staying permeable to materials, accidents, and new forms of attention; what do you believe is at stake, culturally and philosophically, in sustaining that openness over decades, and how do you want your work to function for future viewers, not simply as an aesthetic experience, but as a model of how making can remain an ethical practice of curiosity, resilience, and renewed perception?

I have had a long and varied career, and have enjoyed the fact that I have made a living from my art. Leaving the theatre was tough, but discovering printmaking and the joys of experimenting meant I was able to follow my passion.