Interview with Ashley Gray

https://artofagray.squarespace.com/

Ashley, your recent reflections suggest a return to practice grounded in fatigue and uncertainty, in the psychological consequences of sustained endurance rather than renewed conviction. In this context, how do you understand what calls you back into the act of making: is it a form of discipline shaped by habit and labor, a devotional commitment to meaning making, or something more ambivalent, perhaps a refusal to allow interior experience to remain unarticulated?

I don’t experience the impulse to make as a single or stable motivation. It’s layered, and often contradictory. There is discipline and habit, making art helps my thinking organizes itself, how I remain oriented. But there is also uncertainty, fatigue, and a persistent lack of resolution. I don’t feel called back to the work by renewed conviction so much as by an inability to let interior experience remain unarticulated for too long.

For a long time, the work existed as a more private loop. I made it, lived with it briefly, put it on the websites and moved on. What has shifted is that the work now circulates beyond that website space. External recognition is present in a new form, and while I am extremely grateful, it introduces a new set of pressures that require managing. The challenge is not visibility itself, but learning how to remain aware of it while the work moves through systems that respond faster and louder than I do.

Fatigue has been a long standing condition for me. What’s different now is that this exhaustion is tied to something I care about. I tried withdrawing from making, and that only intensified the tension. It became clear that stopping wasn’t a form of rest, but a kind of disconnection that didn't bring what was suggested it would. Returning to the act of making, keeps me in contact with something that feels like myself.

As the practical realities of being an artist enter my life: art, logistics, bigger internet footprint, they extend the internal landscape I’ve always worked within rather than replacing it. Creating, in this context, isn’t about certainty or direction. It’s a permission to return to myself, to accept the conditions I currently work from, and to continue anyway.

Your work often resists sociability at the level of both persona and image, even as it circulates widely through institutions, platforms, and audiences. How has sustained exposure to these external structures altered your relationship to visibility itself, not simply being seen but being interpreted, fixed, or narrativized? How do you negotiate the psychic cost of participation without capitulating to self-performance?

The work resists sociability because sociability isn’t what it’s oriented toward. The connection I’m interested in isn’t performative or interpersonal, it’s more private, sustained, and often solitary. People have gathered around the work, but that hasn’t altered the conditions under which it’s made. Adjusting the work to accommodate presence or expectation would feel like a loss of integrity and loyalty.

Visibility is also inseparable from the material realities. Circulation, travel, and institutional engagement are financial and logistical questions as much as capacity ones. Much of my participation happens at a distance, through objects and signals that arrive without my physical presence. That distance matters. It allows the work to move without requiring me to occupy a role I don’t know how to inhabit.

At the same time, visibility does change the internal conditions of making. Recent work has emerged from a strange reflective energy, the experience of my art being mirrored back through media, interpretation, and abstraction. This reflection isn’t contained or personal in the way online presence once was with websites, it’s diffuse, and it subtly reshapes how I encounter myself.

For now, I negotiate the psychic cost of participation through distance, I rely on the understanding that I am not exactly what you see. It is my way of remain grounded while the work continues to circulate beyond me.

You have spoken about setting limits in your work, withholding proximity from the viewer, restraining yourself from going too far, and maintaining an internal boundary around what can be shown. How do you theorize responsibility within this economy of restraint? Responsibility toward the viewer’s interpretive freedom, toward the ethical weight of emotional material, and toward your own inner life as a site that is neither fully private nor fully public.

Responsibility, for me, operates both internally and externally, and restraint is what holds those forces in balance. I experience restraint less as withholding and more as clarity a loyalty to how I work, and to what the work can carry. I’m not interested in confession or exposure. Art is a way of approaching something privately, not displaying it, and that hasn’t changed.

Internally, restraint is a form of care. Over-explanation can be disrespectful, to the work and to myself. I don’t believe closeness automatically produces truth, or that a life needs to be fully visible to be meaningful. The work may be shaped by my experience, but it isn’t a vehicle for narrating my experience.

Externally, restraint functions as protection. I feel a responsibility toward the people and relationships that exist around the work, and toward the emotional material itself. Pulling others into visibility, or exploiting connection for momentum or legitimacy, would feel deeply dishonourable to me.

Responsibility toward the viewer isn’t about guiding them along or offering access to my life. It’s about creating the conditions for resonance without instruction. The viewer doesn’t need to understand me, the work only needs to hold enough integrity to meet them where they are.

I experience making art as an honour, something that exists whether it’s witnessed or not. This transition into broader visibility doesn’t alter that condition. It extends it. I remain who I am, and the work remains responsible first to itself.

The figures, hands, and luminous organs that recur in your work appear to oscillate between confession and translation, intimacy and symbol. Do you experience the act of making as one that reveals something essential about you, or as a protective mechanism that allows private affect to be displaced into shared, abstracted form? How does this oscillation shape your understanding of authorship?

I think all art carries an element of confession, whether the artist intends it or not. Choices around material, direction, tone, and style inevitably reveal something about how a person perceives the world. In that sense, I’m fully present in the work. The vulnerability, the luminous elements, the tension between exposure and protection, those are consistent conditions I return to.

At the same time, making is fundamentally an act of translation. Private affect is displaced into a shared, abstracted form, and that displacement is essential. It allows the work to move beyond me without requiring personal exposure. What matters to me is the strength of that translation, whether the work can carry feeling without collapsing.

When my work is received through exhibitions or institutional support, I don’t experience that as recognition of my life, but as an acknowledgment that the translated form can hold on its own. That separation feels important. It allows the work to exist independently, without explanation or disclosure, while still remaining emotionally charged.

Authorship, for me, lives in that oscillation between presence and restraint. I’m fully there, but not as something to be decoded. Even if the subject matter were to change entirely, the work would still be shaped by my way of seeing, my hand. The author isn’t a figure embedded in the image, but a condition that governs how the work comes into being and how far it’s allowed to go.

As your work accrues language around it through interviews, essays, and institutional framing, a composite image of you begins to emerge, constructed by others, often without personal knowledge, yet deeply engaged with the emotional tenor of your practice. How do you inhabit this reflective surface, this interpretive mirror, and what tensions arise between lived selfhood and its discursive doubles?

As language accumulates around the work, through interviews, essays, and institutional framing, an external figure begins to form. I think of this as the art twin: a composite image constructed by others, often without personal knowledge, yet deeply engaged with the emotional identity of the work. Encountering this figure was initially a shock. It didn’t emerge gradually, it appeared all at once, as if I’d stepped online and found a version of myself already circulating, already recognized.

The art twin exists entirely in representation. It lives in books, exhibitions, platforms, awards, google, in places I may not physically inhabit. In that sense, it is fully outside of me. And yet, it carries something real. It reflects my work back with a depth that allows me to see aspects of myself I can’t access internally. Others can’t see the full network of values, memories, and connections that shape the work, but they can return an image that reveals structure, emphasis, and weight. That reflection has been unexpectedly clarifying.

Alongside this is what I think of as the art self: the lived, internal condition from which the work actually emerges. This is where fatigue, uncertainty, pressure, and care reside. The art self experiences the shock of recognition not as coherence, but as intensity, a collapsing into feeling without clear orientation. There is empowerment here, both internal and external, but it arrives without instruction. The art self remains human, private, and at times disoriented, even as the art twin appears increasingly composed.

The tension between the art twin and the art self is where I’m currently situated. There is a distance between them that I’m aware of but don’t yet know how to resolve. Recent work has been, in part, an attempt to acknowledge that gap, not to perform it, but to bridge it carefully for myself. The art twin can carry confidence, even a sense of glory or authority, and I receive that with gratitude. But I don’t fully recognize myself there I have a different goal.

Being invited into spaces of recognition has intensified this awareness. Standing inside institutions or say awards can feel unreal, even crushing, not because of fear, but because of the weight of arrival itself. I don’t yet move easily between these worlds, and for now, that distance feels necessary. I don’t reject the art twin, and I don’t try to inhabit it. If anything it communicates to me that I am acting with honour the stronger the art twin becomes.

Recognition often promises coherence, yet it can just as easily fracture self-understanding by imposing narratives that feel external or premature. Has increased visibility clarified your sense of what your work is doing in the world, or has it complicated it? What strategies do you employ to remain grounded when the public story of your practice diverges from your private, day-to-day experience of being human?

Visibility operates for me in two distinct registers. Internally, increased attention has brought moments of clarity. Seeing the work reflected back has helped me recognize patterns I previously enacted instinctively, particularly around light, control, and restraint. In that sense, visibility has sharpened my understanding of what the work is doing.

Externally, however, visibility introduces distance. A public narrative forms around the practice, an image that exists independently of my daily, human experience as a person. That external figure can be useful, but I do not want it to flatten vulnerability into something fixed or marketable. That’s a line I’m careful not to cross.

Because of this, I remain clear that the external image is not me. It lacks the lived conditions that shape the work, fatigue, uncertainty, loyalty, and care. Grounding myself means staying loyal to my own perception, even as the work circulates more widely which I am very grateful for.

I’m deeply grateful for recognition, especially having never assumed it was possible in such a space. But coherence doesn’t come from visibility. It comes from protecting the internal conditions that allow my work to remain honest. I didn’t enter the art world to become something else, I arrived because there was interest in what already existed. Remaining loyal, for me, means ensuring that any space the work occupies continues to respect that direction and my dedication to it.

Your digital process privileges sensation over system, emotion over orthodoxies of craft, even as it relies on the same technological infrastructures that govern contemporary image making. How do you conceptualize materiality in a medium that is often framed as immaterial, and what does it mean to treat digital space as a site of resistance rather than efficiency?

I experience the digital process less as drawing on a surface and more as inhabiting a space. It functions like a mental mirror, a place where perception can be built, entered. Working in 3D allows me to construct forms rather than in 2D where artists depict them, which aligns more closely with how my inner world operates. Even though the medium allows for correction and reversibility, the meaning of the work lives in the slow acts of building, shaping, and orienting myself within that space.

The substance, for me, isn’t diminished by the digital. It’s relocated. The work still carries weight, pressure, and presence because those qualities come from perception and attention, not from physical matter alone. Digital tools are simply instruments, ways of translating sensation and emotional structure into form. The craft matters only in so far as it allows something human to be articulated clearly and honestly.

Most digital production environments prioritize efficiency, milestones, they have teams, leads, a structure. My practice resists that logic. I’m not working toward products, or deadlines, and any sense of speed in the work comes from the systems of the medium, not from pressure to optimize.

Treating digital space as a site of resistance means refusing to reduce it to efficiency. It means privileging sensation, reflection, my work flow and depth, using the medium to mirror my own mental and emotional processes as it is where I am comfortable. It is the space and language I know.

Many of your works stage moments of suspended time, thresholds where an action has just occurred or is about to unfold. How do you think about temporality as an emotional structure rather than a narrative one, and what does this suspended middle allow you to articulate about memory, trauma, or endurance that linear progression cannot?

I think of temporality in my work as an emotional structure rather than a narrative one. Linear progression tends to diffuse tension through expectation, the viewer anticipates what comes next, and the emotional charge softens if they have a template. By working with suspended or fragmented time, I can allow feeling to surface repeatedly at each images instance.

These suspended moments function as thresholds rather than events. Something has just happened, or is about to happen, but the work refuses to move forward. That refusal creates a space where past, present, and future can coexist. In works like 'Mercy 2019' where multiple versions of myself appear simultaneously, time isn’t progressing, it’s layered. Memory, endurance, and trauma don’t operate linearly in lived experience or in reflection, and I want the structure of the work to reflect that reality.

Freezing time isn’t a strategy so much as just how I work. I’m drawn to moments that carry density and significance rather than sequence, moments that lodge themselves in perception and refuse to pass. By pulling the viewer to random instances of time, the work shifts attention away from outcome and toward presence. What matters isn’t what comes next, but what is already here, unresolved and still active, what you are seeing only, in the instance that you see it.

Light in your work functions not only as illumination but as scarcity, pressure, and ethical charge. How do you understand light as both a symbolic economy and a perceptual strategy, and what does its deliberate limitation suggest about the fragility of hope, clarity, or connection within contemporary conditions of crisis?

Light is scarce in my work because that’s how I experience it in the world, as pressured, concentrated, and rare rather than abundant. Meaning and hope, as I perceive them, tend to gather around singular points of human presence rather than existing as stable environmental conditions. A single point of light in the vast darkness of reality's backdrop, like stars.

That limitation isn’t a symbolic strategy so much as an inevitability. Certain moments imprint themselves on me with great intensity, fragments of perception that remain charged long after they occur. When I work, my goal is to translate my perception honestly. If hope or light were experienced as plentiful, it would appear that way in the images my art and my style. Light, is not, and so it does not.

Light operates both scientifically and symbolically because perception itself can extract meaning. I observe how light behaves, where it falls, what it isolates, what it protects, and that visual data becomes meaning through attention. My technical understanding allows me to intensify contrast and pressure, but the source is perceptual rather than conceptual. What might read as drama or boldness is, for me, a form of accuracy.

Within contemporary conditions of crisis, limiting light acknowledges fragility rather than denying it. In my day to day work as a first point of contact for council services, I encounter many form of light for example the unguarded curiosity of children held inside difficult situations, people who are somewhat desperate but still have inner resilience, those who seek understanding and guidance for empowerment not ease. Those moments are brief and exposed, but they carry enormous weight because they exist within our reality that offer little protection. Like the other perceptual experiences, I add them to my mind as emotional data that support an image like 'Distress Signals 2020'.

That dynamic, human light persisting inside indifferent systems, stays with me. I’m not interested in making political statements. I’m showing states as I feel them. The restrained light holds attention on what remains possible without exaggeration. It suggests that hope, clarity, and connection still exist, but they are fragile, momentary, and carried by human beings rather than guaranteed by the universe.

Working under the name Human operates as a conceptual erasure of biography, yet your images remain deeply saturated with emotional specificity. How do you reconcile this gesture of anonymity with the undeniable presence of lived experience in the work, and in what ways does the removal of personal markers paradoxically intensify the autobiographical force of your imagery?

Working under the name Human is not a rejection of experience, but a refusal to claim ownership over it. Even when the work draws from something I have lived through, I don’t think of it as autobiographical in the traditional sense. What matters to me isn't what happened to me specifically, but what can be recognized or felt by another person through the image. I use my perception as a human being, not my identity as an individual.

The imagery can feel intense or intimate, and I understand why that is often read as confession. But my intention is not to present myself or to be known. I’m not interested in biography or self display. The name Human creates distance between me and the viewer and separately also me and the art twin, so my work doesn’t collapse into personality. The image has to stand on its own, without explanation, carrying emotion as something shared rather than something owned.

In that sense, anonymity doesn’t weaken the presence of lived experience in the work, it clarifies it. What remains is not my story, but a trace of human perception translated into form. I see the artwork as a vehicle: human to object to human. I’m not here to stand beside it or to be applauded for it, you do not like the art because I made it, you like me because that is where the art came from. I’m here so that the work exists, holds something human, and allows another person to encounter it without needing to know me.

Your compositions often position the viewer not as a detached observer but as an implicated presence, occupying a perspective that feels ethically and emotionally charged. How do you engineer this participatory gaze, and what responsibilities does it impose, both on you as the maker and on the viewer as a co-producer of meaning?

I don’t think of the viewer as a detached observer. From the beginning, I’m conscious of where the viewer is positioned, emotionally and perceptually, and I try to place them inside the work rather than in front of it. This happens through scale, framing, perspective, things like this, but more importantly through the emotional logic of the image. I want the viewer to feel present, as if they are encountering something rather than simply looking at it like I do.

That sense of implication creates responsibility on my side as the maker. I’m careful not to manipulate or overwhelm, but to be precise. If the image is emotionally charged, it has to be honest and considered, not sensational. My responsibility is to construct a space where feeling can occur without instruction, where the work holds enough clarity that the viewer can enter it on their own terms.

The responsibility also shifts to the viewer. Meaning isn’t delivered, it’s completed. The viewer brings their own experience, memory, and sensitivity into the encounter, and that becomes part of the work. In that sense, the image functions as a shared space rather than a statement. I see the viewer not as an audience, but as a co-producer of meaning, another human meeting the work and finding something within it. All my works to me have value it is the audience that make some of them note worthy and I cant not do that nor do I demand it.

The symbolic vocabulary in your work draws from a convergence of mythic, spiritual, and digital languages without settling into a fixed semiotic system. Do you think of symbolism in your practice as something discovered rather than designed? How do you balance the desire for interpretive openness with the risk of symbolic collapse or over determination?

I don’t think of symbolism in my work as something I design or assign fixed meanings to in advance. It’s something I discover through perception, memory, and care. Many of the symbols I use already exist across religion, spirituality, and contemporary culture: halos, light, demons, chains, bodies, but I’m not interested in them as belief systems. I’m interested in how these forms carry weight because they’ve been looked at, questioned, and lived with over time.

The symbols work because they are encoded with meaning through my attention to them like the starfish. Even when a symbol begins as something private or specific, a small object, a memory, a gesture, it holds because I care deeply about it, it has significance, gravity. That care is what gives it charge. If I didn’t care, the symbol would be empty. I don’t expect the viewer to understand my personal meaning, but they can feel that the symbol means something.

I’m careful to keep symbols open without letting them collapse into ambiguity or become overly fixed. I don’t want them to function as explanations or instructions. Instead, they operate as containers, holding intensity without resolving it. In that sense, the meaning isn’t delivered but encountered. The symbol doesn’t tell the viewer what to think, it simply refuses to be neutral. What it carries is human perception translated into form.

Your practice frequently foregrounds endurance, hands reaching, bodies straining, and figures suspended in inhospitable environments. How do you situate endurance philosophically within your work? As resistance, as quiet persistence, or as a condition imposed by systems that leave little alternative. How does this framing complicate more romanticized narratives of resilience?

Endurance in my work isn’t a simple story of heroism or triumph. It’s a condition, often imposed by systems, circumstances, or forces outside the individual’s control, that demands quiet persistence rather than loud resistance. The bodies reaching or straining are caught in this tension: neither fully surrendering nor fully fighting, but existing in a state of ongoing survival. This endurance isn’t always a choice, sometimes it’s the only way forward.

Philosophically, I’m interested in endurance as a lived experience and that complicates a more romanticized narrative of resilience. Resilience is often told as a story of overcoming, of emerging stronger and victorious. My work resists that neat resolution. Instead, it acknowledges endurance as ongoing, ambiguous, and sometimes exhausting, an emotional and physical persistence that doesn’t always end.

This framing invites the viewer to reconsider what it means to endure. It’s not about heroic breakthroughs but about the everyday realities of existing within structures that leave little room for escape or transformation. The tension between resistance and acceptance, struggle and stillness, is where the emotional weight of the work lies.

In building an independent ecosystem of art, connection, and digital storytelling, you seem to resist both institutional dependency and the branding logics of platform culture. What does autonomy mean to you in this context, and how do you imagine sustaining emotional truth within an art economy that often rewards visibility over vulnerability?

Autonomy, for me, means maintaining the ability to work without having my emotional or creative decisions shaped by external reward systems. It’s not about isolation or refusal, but about distance, enough space to protect the integrity of the work. I’m interested in building an ecosystem where art, connection, and storytelling can exist without being immediately translated into metrics, branding, or performance.

I’m wary of both institutional dependency and platform culture because they often encourage visibility at the expense of more authentic drivers for art. When visibility becomes the primary currency, emotional truth risks being simplified, anaesthetized, or repeated constantly until it loses its charge. My interest lies in sustaining work that remains honest even when it’s quiet, slow, or difficult, work that doesn’t need constant reinforcement to exist.

Sustaining emotional truth in this context means accepting a different pace and a different scale of recognition. I don’t see autonomy as control or self promotion, but as responsibility, the responsibility to protect what feels human in the work. If the art holds, it’s because it hasn’t been optimized for attention, but allowed to remain vulnerable, and my art self to remain a servant to what I believe in rather than money or exposure, trends etc.

Your stated aim is not clarity but resonance, a desire for the work to sit quietly with the viewer and reflect something back to them. How do you measure success in such an intangible register, and what does it mean to commit to resonance as a critical and philosophical stake rather than an aesthetic effect?

I don’t measure success through clarity or explanation, because my work is not about teaching or instructing. Success emerges when the work carries something human that can be felt independently of me, when the viewer encounters an image and experiences recognition, reflection, or emotional contact without needing to know my story. This isn’t about approval or interpretation, it’s about service, loyalty.

Resonance is not an aesthetic effect, it is a critical and philosophical stake. It shapes every decision I make, from composition to symbol, scale to position. Each element is treated as a vessel for perception and feeling, not as decoration or a narrative device. Committing to resonance means that the work must function on its own terms, in the space between human experience and object, rather than being reliant on explanation, biography, or spectacle, I communicate a type of, I didn't get to understand why, so the viewer wont either. You only get, what I can offer you, nothing more.

In this sense, resonance is both the measure and the purpose of the work. It is the responsibility of the artist to create strong conditions for that experience in each work, and the responsibility of the viewer to meet it with attention for that art style. The work is successful not when it is seen, but when it is received, held, and carried forward, when something human is transmitted quietly from one person to another, through an object, which happens for me to be digital image.

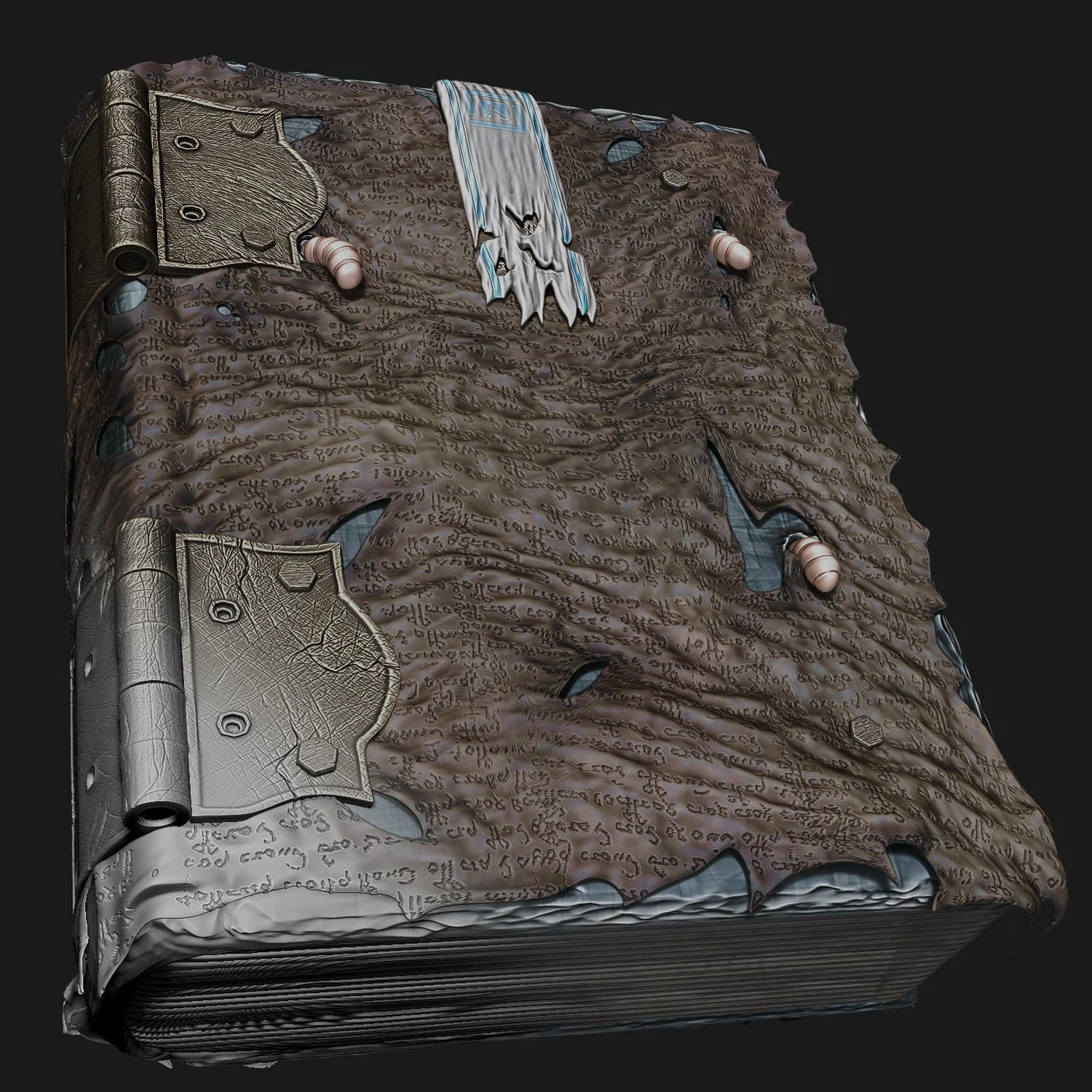

Are you Sure Digital 2025

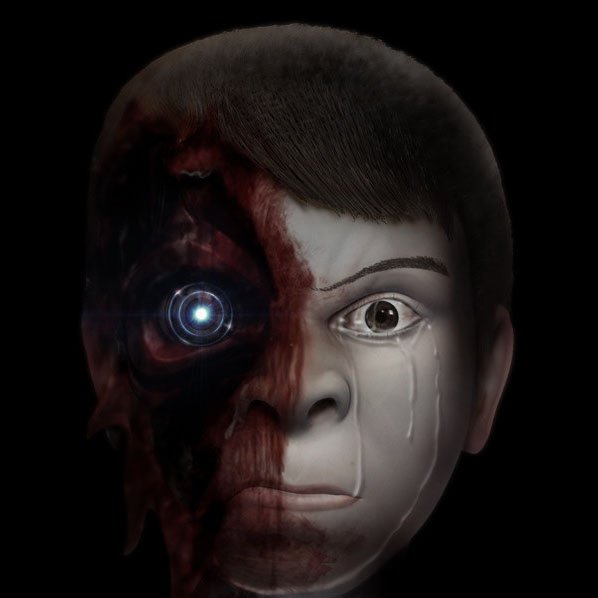

Be Brave Digital 2020

Ethereal Blue Digita 2015

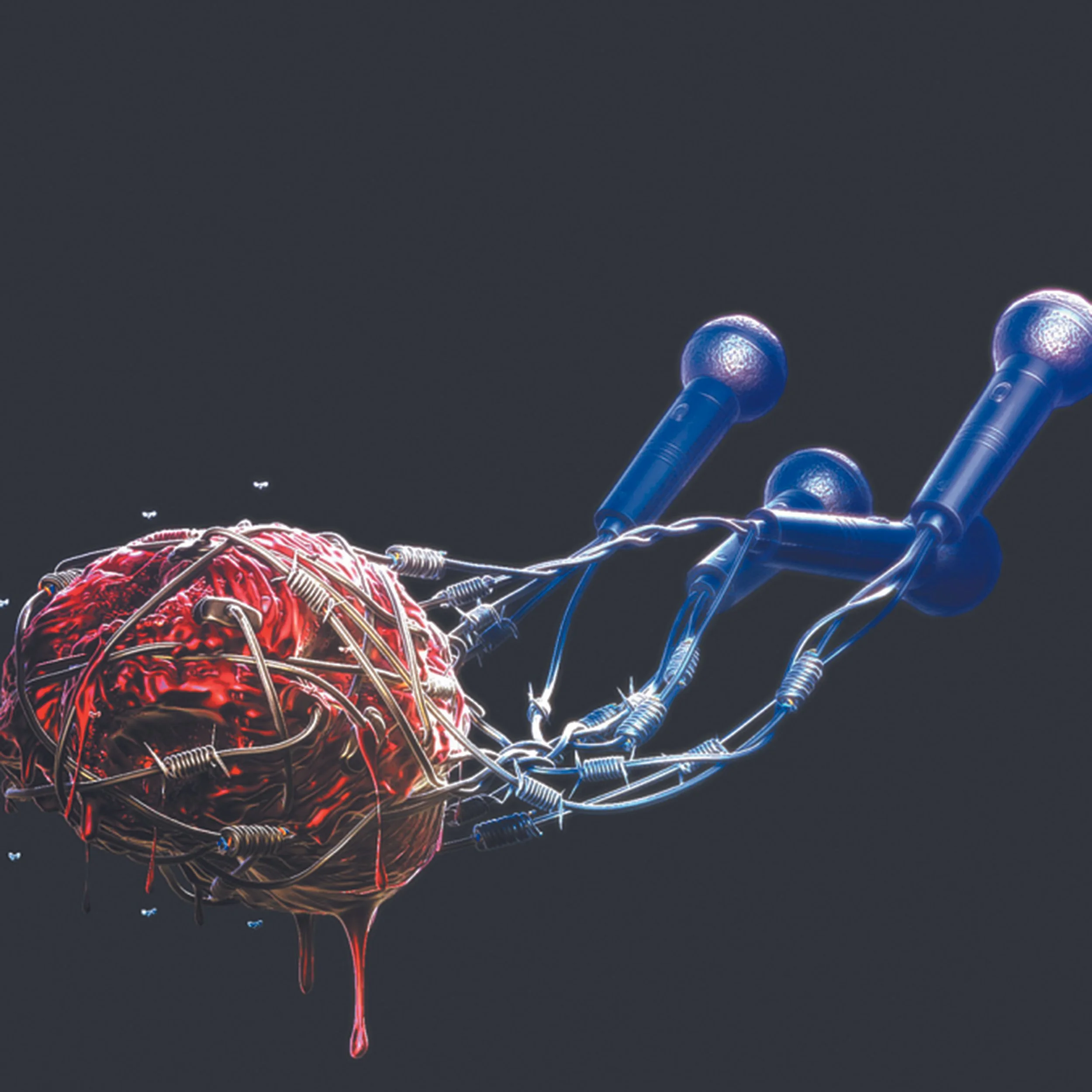

The Brain Controls Everything Digital 2018

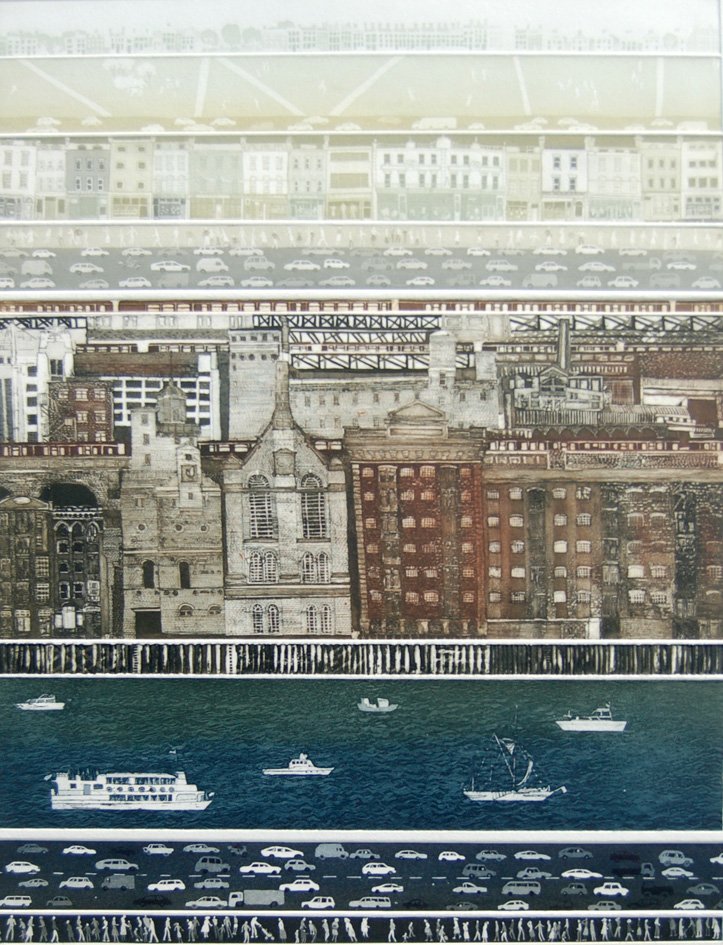

The Luminous Stage Digital 2025

Blue Heart Forever Digital 2017

Spark Digital 2015

I Wish there were Words Digital 2016

Black Star Children Digital 2018