Interview with Björn Carlsson

Björn, your practice proposes photography as a site of authorship that is neither merely indexical nor simply illustrative, but constructed through a painter’s sensibility and an editor’s discipline. When you describe post-production tools as a palette and brush, what precise kind of authorship is being claimed, and how do you negotiate the conceptual threshold where enhancement becomes composition, and composition becomes a new image with its own ontological status, rather than a refinement of what the camera first registered?

My practice is based on the premise that photography does not end at the final curtain, but rather begins there. By using post-production tools such as a palette and brush, I shift the focus from photographic representation to artistic creation.

Copyright through ‘work height’

The type of copyright I claim is not linked to the purely indexical – that is, that I ‘was there and pressed the button’. Instead, I claim copyright based on work height through subjective choices.

When I treat the raw file as a canvas, it is my unique aesthetic decisions (colour balance, light modelling, selective focus) that constitute the protectable work. In legal terms, this means that the image achieves such a degree of originality that no one else, with the same raw material, could recreate exactly the same end result.

The borderland: Enhancement vs. Composition

The boundary where an ‘enhancement’ becomes a ‘new composition’ is where editorial discipline meets painterly vision:

Enhancement is about correction: reproducing reality as the eye remembers it (technical optimisation).

Composition (and thus a new work) arises when I actively guide the viewer's gaze by adding, subtracting or dramatically rearranging the components of the image.

When I use the brush to enhance a light that was not there, or a palette that fundamentally changes the mood, I negotiate away the documentary heritage. I stop ‘reporting’ and start ‘telling’.

The new ontological status

This is where the image gets its own story of existence. Through my process, the image becomes not a ‘refined version of reality’, but an autonomous visual construction.

Its ontological status shifts from being a trace of a past moment to being an object in the present. In this context, the camera has the same role as a sketchbook for a painter: it collects raw data, but it is in the ‘development’ (painting) that the soul and truth of the image are formulated. It is not an image of something, it is an image in itself.

‘I don't photograph what I see, I photograph what I want you to feel – and in that gap, my copyright is born.’

The language of “giving the photograph an artistic character” implies that the photograph, as captured, is not yet fully itself, but a latent field of values waiting to be articulated. How do you understand the RAW file as material, not just data, and what ethical or philosophical stakes emerge for you in treating the captured image as an unfinished substrate whose meaning is produced through extraction, emphasis, and atmospheric calibration?

Considering the RAW file as a ‘latent field’ is an accurate description of my work process. For me, the RAW file is not a finished photograph, but a digital equivalent of an unexposed sculpture in a block of marble – it contains all possibilities, but requires an act of will to become a work of art.

The RAW file as material, not just data

I don't see the RAW file as a static file, but as a plastic substance. Where a JPEG file is a locked decision, the RAW file is a container of information that extends far beyond the immediate perception of the human eye at the moment of exposure.

When I approach this material, it is an extraction process. I dig into the shadows and tone down the highlights to find the drama that the camera's sensor physically recorded, but which has not yet taken shape visually. The materiality lies in its stretchability; how far I can push the pixels before they break down, and how much ‘light matter’ is actually stored in the binary.

The ethical dimension: Truth vs. Experience

This raises an interesting ethical tension. If photography has traditionally been regarded as proof that ‘this has happened,’ my processing means that I am moving away from documentary testimony.

The ethical question I ask myself is: Where is the line between clarifying a feeling and falsifying an event? My answer is that my loyalty lies not with the mechanical recording of the camera, but with the subjective truth of the moment. By calibrating the atmosphere and emphasising certain elements, I try to recreate not what the lens saw, but what the presence felt like. It is an ethic that prioritises emotional honesty over optical honesty.

The philosophy behind the unfinished medium

When I treat the image as an unfinished medium, I challenge the idea of photography as a final moment. Instead, photography becomes a two-step process:

1. Collection: A physical reaction to light and space.

2. Articulation: An intellectual and aesthetic processing where meaning is created.

This means that the image's ‘ontological status’ (its essence) is transformed. From being a by-product of a chemical/electrical process, it becomes the result of human intention. It is in this ‘atmospheric calibration’ that I step in as a co-creator rather than just an operator of a machine.

‘The RAW file is the silence before the first chord. It is in the processing that I choose the key.’

You move between the grand landscape and the intimate, between wildlife and architecture, between remote Nordic geographies and urban encounters. How do these shifts in motif reorganize your sense of scale, temporality, and attention, and what remains consistent as a structuring principle across such different subjects: a compositional grammar, an emotional temperature, a politics of looking, or an underlying theory of what the world should look like when translated into an image?

Moving between the timelessness of nature and the fleeting architecture of the city is not a change of subject for me, but a change of scale. Beneath the surface, the same fundamental questions are asked, regardless of whether the motif is a mountain wall or a concrete façade.

Scale and temporality: From the geological to the urban

The shifts in subject matter force an elasticity in my attention.

In the Nordic landscapes, I encounter a geological time; there, the scale is monumental and man is insignificant. Here, my attention is focused on persevering, waiting for the right light that defines the space.

In urban encounters or architecture, time is faster, more nervous. Here, the scale is human and the gaze is more searching for rhythm and order in a chaos of impressions.

The constant principle: an emotional temperature

Despite the diversity of motifs, my emotional temperature remains constant. I am almost always searching for a certain kind of silence. Even in a dense urban environment or an image of a flower, I try to distil a sense of stillness and isolation.

This is my primary structuring principle: to apply the same calm, almost sacred gaze to a modern building as to an ancient mountain. It is about finding the point where the motif ceases to be a ‘thing’ and instead becomes a carrier of mood.

Compositional grammar as politics

My ‘grammar’ is often austere and reduced. By using a consistent aesthetic – often working with a muted palette and conscious control over the fall of light – I create a politics of viewing.

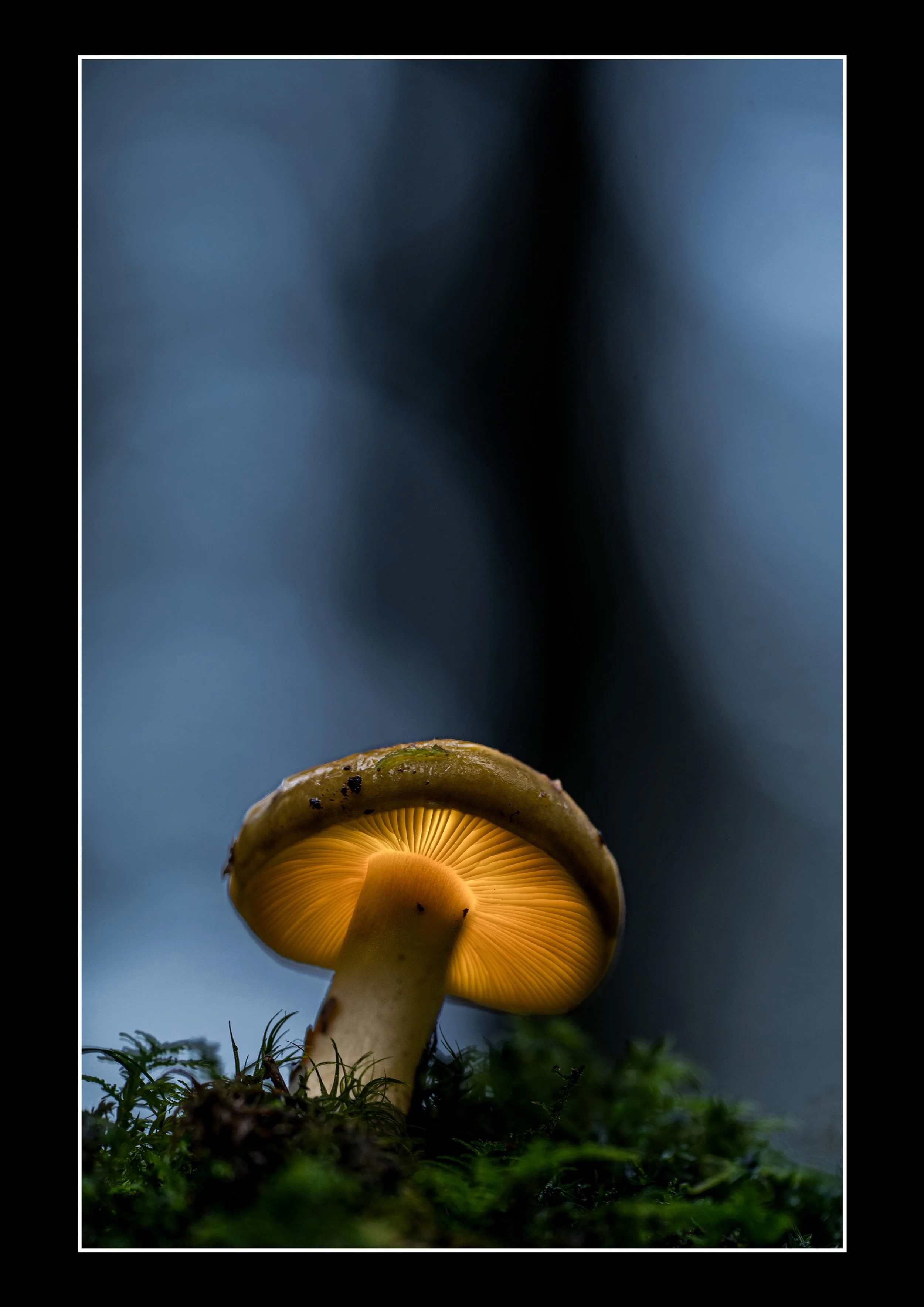

By giving a solitary mushroom the same compositional weight as an architectural icon, I assert their equivalence. I translate the world into an image where everything – organic as well as artificial – obeys the same universal laws of form, light and shadow.

The theory of the image as translation

My underlying theory is that when translated into an image, the world should not look as it ‘is,’ but as it feels in a state of maximum concentration.

The image is a place where I can bring together the great distances and the small details in a common framework. Architecture becomes nature, and landscape becomes architecture. This translation is my method for making the world comprehensible and coherent.

‘For me, there is no difference between a cliff face and a house facade; both are surfaces that capture light and tell the story of the passage of time. My task is to find the silent frequency where they meet.’

“Less is more,” and the pursuit of simplicity suggests a refusal of visual noise, yet you also speak of layers, LUTs, presets, and composite additions as an expanded toolkit. How do you reconcile minimalism as an aesthetic ethic with an increasingly complex technical workflow, and where do you locate the minimal: in the visible outcome, in the conceptual economy of decisions, or in a disciplined resistance to spectacle despite the capacity to produce it?

Achieving a minimalist look often requires more precision, not less. A complex toolbox with layers, LUTs and composites does not serve as decoration, but as a surgical instrument.

Precision over volume: Using advanced tools allows you to isolate and remove distractions (visual noise) with a level of accuracy that simpler tools lack.

Invisible complexity: The technical weight of the workflow is used here to ‘clean up’ the image so that the viewer does not have to see the technology. The better the tools, the easier it is to make the difficult look simple.

Minimalism in decision-making (Conceptual economy)

Minimalism is found primarily in intellectual discipline. Having access to ‘spectacular effects’ but choosing not to use them is an active choice.

The choice to refrain: An artist with a limited toolbox is a minimalist by necessity. An artist with an unlimited toolbox who chooses simplicity is a minimalist by conviction.

Strategic layer management: Each layer or LUT in the workflow should not add anything new, but rather refine what already exists. It is a ‘subtractive’ methodology where technology is used to distil the essence of the subject.

The disciplined resistance.

There is a temptation in technical ability; when we can do something spectacular, we often want to show it off. Minimalism as an ethic acts as a filter here:

Ethical integrity: Resisting the spectacular is about respecting the truth of the subject. If an effect does not serve the story or the emotion, it is seen as pollution.

The result vs. the journey: Minimalism resides in the visible result, but it is made possible by a disciplined work process. A complex node structure in a colour grading programme is just a way to control the light so naturally that it looks as if no one has touched it.

‘Minimalism is not the absence of something, it is the perfect amount of something.’

Your stated attraction to cold Nordic places carries with it a long history of the sublime, the frontier, and the romanticization of the North as purity, extremity, or distance from the social. When you photograph Spitsbergen, Lofoten, Greenland, the Faroes, or Iceland, how do you position your images in relation to that historical inheritance, and what strategies do you use to avoid turning landscape into a cultural fantasy while still allowing it to retain its intensity and affect?

From the Sublime to the Intimate

Historical heritage often emphasises the “grand” – the vast expanses that make humans feel small. My strategy is to frequently shift focus from the monumental to the specific and tactile.

Strategy: Instead of just seeking out the wide views (which easily turn into ‘cultural fantasies’ about the untouched), I seek out the texture of the landscape: the moisture in the moss, the cold in the stone, the actual impact of the flat light on the material.

Purpose: By making the landscape physical rather than merely symbolic, the focus shifts from a romantic idea to a concrete presence.

Documenting the ‘Impure’ in the Pure

One danger of romanticising the Nordic region is the idea of ‘pure’ nature as a place beyond human influence. To avoid the landscape becoming a fantasy, I sometimes choose to include the imperfections or the quiet human presence that actually exists.

Strategy: I avoid consciously ‘cleaning’ the image of elements that do not fit into the myth of the wild. It is about accepting the landscape as it is today, rather than how it looked in a 19th-century painting.

Purpose: It creates a friction that anchors the image in the present and prevents it from becoming an escapist backdrop.

Atmosphere as Physical Condition, not Decoration

The intensity of Nordic light and weather is often used as a dramatic effect. Instead, I try to treat these elements as functional conditions.

Strategy: I work with a disciplined resistance to the ‘over-spectacular’. Fog is not there to create mystery (a cultural construct), but because it obscures sightlines and changes how sound and light move.

Purpose: By approaching the phenomena with an almost objective gaze, the image retains its power without tipping over into melodrama.

Distance from the Social as a Self-Imposed Isolation Cell

The distance from the social. This is where the biggest challenge lies: not portraying the Nordic region as an empty stage for human introspection.

Strategy: I try to position the camera not as an observer that ‘owns’ the view, but as part of the ecosystem. It is about capturing the landscape's own agency – that it exists independently of my gaze.

Purpose: To break down the romantic idea of nature as a mirror for human emotions and instead allow it to be an autonomous force.

"My position is to acknowledge the legacy but to demystify the process. I seek the intensity of the landscape by being hyper-present in its details rather than reproducing its myths".

You describe photography as “creating order in chaos,” an idea that is simultaneously formal, psychological, and philosophical. What is the nature of the chaos you are addressing: visual complexity, the contingency of weather and wildlife, the unpredictability of travel, or the existential disorder of contemporary life? In making order, what is being clarified, what is being excluded, and how do you remain attentive to what the act of ordering might silence or misrepresent?

When I talk about chaos, I am not referring to a single factor, but rather to an intertwining of several:

Perceptual chaos: The world has no boundaries. The eye and brain are constantly bombarded by an endless barrage of light, movement and matter. Photography is about setting a limit to this barrage.

The unpredictability of nature: Weather, lighting conditions and wildlife are forces beyond our control. It is a dynamic chaos that requires immediate adaptation.

The existential noise: In a modern world of constant information and fragmented impressions, the viewfinder acts as a funnel. It forces me to focus on one thing at a time, which dampens the inner noise.

What is clarified and what is excluded?

When I create order through composition and technique, a radical selection takes place.

What is clarified: Relationships. By isolating a motif (e.g. a lone rock against a horizon), I clarify the character of the motif and its relationship to space. I highlight structures, rhythms and contrasts that would otherwise be lost in the complexity of the whole.

What is excluded: Anything that distracts from the central idea. This could be a power line, a cluttered foreground or a colour that disrupts the harmony. But above all, time is excluded – the photograph freezes chaos in motion into orderly stillness.

The ethical dilemma: What is silenced or distorted?

This is the most critical part of the process. Creating order is an exercise of power over reality.

The danger of embellishment: An overly strict order can erase the soul of the landscape. If I clear away all the ‘clutter’ or force nature into a perfect golden ratio composition, I risk turning a living place into a sterile product.

Keeping the ‘wildness’: To stay aware of what order silences, I try to leave a bit of friction in the image. It could be asymmetry, an unexpected shadow, or blurriness that reminds me that what I've captured is just a snippet of something much bigger and wilder.

Conscious distortion: I acknowledge that the image is a distortion. By being transparent about my choices – that I use composites or specific colour palettes – I acknowledge that order is a human construct, not an objective truth.

"Order is not the goal in itself, but a language for making chaos comprehensible. What I seek is a “living order” – a composition that is tight enough to provide clarity, but open enough to allow the landscape's own voice and unpredictability to breathe through the surface".

Rhythm, repetition, pattern, breath, waves, heartbeat: your vocabulary points to the body as a model for perception and to the world as something that can be read through recurring structures. How consciously do you compose for a viewer’s embodied response, and in what ways do you think your photographs produce a temporal experience, not just a visual one, shaping how long the eye stays, how it moves, and how it returns?

I compose not only for the eye, but for what I call ‘the kinetic gaze.’ It's about creating a visual path that mirrors physical movements.

Waves and breath (Frequency): By using repetitive elements – such as the curves of the dunes, the trunks of the forest or the lines of the waves – I create a visual pulse. A dense rhythm can create a feeling of energy or tension (high pulse), while wide, horizontal lines act as deep exhalations that lower the viewer's shoulders.

Balance and gravity: We have an innate sense of up and down, weight and lightness. By placing ‘heavy’ elements (dark areas, massive cliffs) at the bottom of the image, I create a sense of stability. Breaking this can create a physical sensation of vertigo or weightlessness.

The temporal experience: How the eye wanders

A photograph is a frozen second, but the experience of it is a process over time. I use specific strategies to guide the viewer's ‘journey through time’ in the image:

Entry and rest: I often create clear entry points into the image, a visual ‘threshold’. Once the eye has entered, I place resting points – areas of negative space or minimal detail where the gaze can pause, like a pause in breathing.

Visual loops: Instead of leading the eye out of the image, I compose with circular or recurring structures. This means that when the eye reaches an edge, it is led back into the image again through a rhythmic connection. This creates a meditative timelessness rather than a linear viewing experience.

Patterns as universal readability

Repetition and patterns are the brain's way of simplifying chaos. When the viewer encounters a structure reminiscent of fractals in nature or the pattern of a heartbeat graph, there is an immediate recognition.

The echo of the body: By finding structures in the landscape that correspond to the body's internal forms (veining resembling blood vessels, cracks resembling skin), a deeper empathetic connection between humans and nature is created.

Duration through richness of detail: By concealing small variations in large patterns, I force the eye to shift between the big sweep (the rhythm) and the small deviation (the unique). This oscillation between macro and micro prolongs the time the viewer spends with the image.

”My photographs are intended to function as a visual breathing exercise. By using rhythm and pattern, I create an order that not only clarifies what is seen, but also resonates with the viewer's own physicality. Success is not measured by how quickly the image is ‘understood’, but by how long the viewer can rest in its pulse without wanting to look away”.

You have emphasized that a poorly composed image cannot be rescued by tools, placing composition as a foundational criterion rather than a flexible outcome. What constitutes composition for you beyond arrangement: is it an ethical stance, a way of respecting the subject, a form of accountability to the viewer, or a method of thinking through the world? How do you train composition in the field, especially in environments where control is limited and conditions are unstable?

Beyond the purely visual, I see composition as a silent agreement between the photographer, the subject and the viewer:

Respect for the subject: Composing well means giving the subject its rightful space. By choosing exactly what to include and what to exclude, I reveal the intrinsic value of the landscape. A sloppy composition is a sign of inattention – a way of passively consuming a view instead of actively understanding it.

Responsibility towards the viewer: I see composition as a generous act. By creating order in visual chaos, I guide the viewer's gaze and save their energy, allowing them to go straight to the emotional experience instead of having to struggle to interpret the image.

An ethical stance: It's about integrity. If I can't find a composition that speaks truthfully about the place at that moment, I often choose not to press the shutter. It is a disciplined refusal to produce ‘visual noise’.

Training in the field: Strategies for the uncontrollable

In environments where weather, light and terrain are unstable, composition is less about ‘creating’ and more about ‘listening’.

Visual subtraction: My most important method in unstable environments is to start with what's distracting. Instead of looking for what to add, I look for what I can take away. By simplifying under pressure, I reduce the risk of the image feeling cluttered when chaos strikes.

Searching for ‘anchors’: In a chaotic landscape (e.g., a snowstorm or a whipping sea), I look for a fixed point—a visual anchor. It could be a rock, a horizon line, or a colour contrast. Once the anchor is in place, the rest of the image can be allowed to be dynamic and unstable.

Physical positioning: In the field, I practise composition through movement. Often, a perfect composition is a matter of centimetres of camera position. I train my ability to see how perspective lines change when I lower the tripod or take a step to the side,

long before I look through the viewfinder.

Predicting rhythm: In environments with movement (waves, clouds), I practise anticipating the temporal aspect of composition. I compose for where a wave will be, not where it is now. This requires an intuitive understanding of the rhythm of the landscape.

”For me, composition is distilled attention”.

Your use of presets and LUTs “to speed up the flow” suggests a productive tension between intuition and system, spontaneity and repeatable structure. What does speed do to judgment in your process: does it protect the initial emotional truth of the encounter, or does it risk standardizing perception? How do you ensure that acceleration does not become aesthetic automation, and that the image retains a specificity that resists template?

Using presets and LUTs isn't just about saving time; it's about preserving an emotional direction. The tension between the intuitive and the systematic can be broken down into three key perspectives:

Speed as a safeguard for the ‘initial truth’

There is an inherent risk that your eyes will ‘get used’ to a raw file the longer you work with it. By quickly applying a basic structure – a LUT that corresponds to the intended vision – you can lock in the initial feeling before logical, critical thinking takes over and ‘over-edits’ the nerve of the image.

Advantage: Speed minimises decision fatigue

Effect: You retain the immediate reaction from the moment the image was taken.

The risk of aesthetic automation

The danger arises when the tool becomes a filter rather than a foundation. If the process stops at a preset, perception risks becoming standardised; we begin to see the world through the templates we have access to. To counteract this, the system must be seen as a springboard, not a final destination.

Warning sign: When the image begins to resemble a genre rather than a unique moment.

Strategy: Consciously breaking the template in the last 10% of the work – adding the ‘human friction’ that an algorithm would never suggest.

Ensuring specificity against templates

To ensure that acceleration does not lead to automation, active dialogue with the material is required. Specificity is preserved by identifying what makes this particular image unique – it could be a specific light source, a skin tone or a shadow – and then protecting these elements from the general influence of the LUT.

‘The system gives me the structure, but intuition gives me the deviation. It is in the deviation from the template that the real image lives.’

You draw a careful distinction between composite practices and montage, implying a different conceptual intent even when the result involves added objects and backgrounds. How do you define that difference in terms of truth claims, coherence, and viewer trust? What do you want the viewer to understand about the reality status of the image, and how do you manage the line between an image that feels internally inevitable and one that reveals its construction as a critical dimension?

For me, distinguishing between composite and montage is not a technical distinction, but rather a question of the image's ‘contract’ with the viewer. It is about whether the image strives to be a coherent window onto a possible world, or an open critical dialogue about its own creation.

Composite: Internal inevitability

When I work with composite practices, the goal is often to create an image that feels internally inevitable. Here, added objects and backgrounds are integrated so seamlessly that they obey the same physical laws as the original motif – light, shadow and atmosphere interact to create a unity.

Truth claim: Here, the truth lies not in the fact that the event took place in front of the camera, but in the emotional and aesthetic coherence.

Trust: The viewer's trust rests on my offering a credible vision. I want the viewer to accept the reality of the image without being distracted by technical joints, so that they can focus on the core of the image.

Montage: The critical dimension

Montage, on the other hand, carries a different intention. It is based on the juxtaposition of fragments. By allowing different realities to collide, rather than merge, montage reveals its own construction.

Reality status: Here, truth is relational. By breaking the illusion of a unified space, I invite the viewer to engage in critical reflection. The image says: ‘I am a construction; see how these parts speak to each other.’

Context: Montage is used when I want the viewer to understand that the image is a compilation of ideas rather than a representation of a space.

The boundary: Trust and doubt

I manage the boundary between the inevitable image and the revealed construction by controlling the degree of friction.

In the ‘inevitable’ image, I want the technique to be invisible in order to protect the narrative truth.

In the ‘constructed’ image, I deliberately leave small discrepancies. These may be subtle differences in perspective or a scaling error that acts as a visual footnote.

”My intention is that the viewer should never feel deceived, but rather challenged. If the composite is a symphony in which all instruments form a sound, the montage is a collage poem in which each word retains its own story. By navigating between these, I can communicate different levels of reality – from the subjective dream to the analytical commentary”.

Much of your work emerges from encounters with nonhuman life and with places that can seem indifferent to human narratives. How do you approach the question of anthropocentrism in nature photography: the temptation to project mood, morality, or drama onto landscape and wildlife? In crafting atmosphere through editing, how do you keep the image from becoming a mirror of the self alone, while still acknowledging that every photograph is a shaped perception?

Approaching nature without succumbing to anthropocentrism – the tendency to place humans and our feelings at the centre of everything – requires constant intellectual vigilance. It is about shifting focus from talking about nature to listening to it.

Indifference as liberation

Instead of seeing the landscape's indifference to humans as something cold, I see it as a liberating truth. By refraining from projecting human drama or morality onto wildlife or a mountain wall, I can approach their intrinsic value.

Strategy: I look for what in philosophy is called ‘the radically other’ – that which does not need us to be complete.

Goal: To create images where the landscape does not ‘respond’ to the viewer's gaze, but rather just is.

Atmosphere versus projection

When I create atmosphere through editing, there is a high risk that the image will become a mirror of my own state of mind. To avoid the image becoming a pure ‘aesthetic colonisation’ of the place, I use the technique to reinforce the inherent logic of the place rather than my own mood.

The shaped perception: I acknowledge that the image is an interpretation. But instead of applying a filter of ‘melancholy’ or ‘power,’ I try to highlight the elements that were actually there – the harshness of the light, the density of the silence, or the weight of the materiality.

Editing as sharpening the gaze: Editing here serves as a way to clear away the noise that disturbs the encounter with the non-human, in order to arrive at a purer observation.

The ‘non-human’ image

How do you avoid the image becoming a mirror? By letting the subject's own geometry, rhythm and time scale dictate the composition.

If a landscape feels static and silent, I let the editing emphasise that very stillness, even if it goes against the human impulse to want ‘excitement’ or ‘narrative’.

It's about daring to let the image be boring, empty or inaccessible – qualities that often belong to nature, which doesn't care about our presence.

‘I don't want the image to be a story about me, but a report from a place where I just happened to be a temporary guest.’

”The answer lies in recognising that, as a photographer, I am a filter, but that my goal is to make that filter as transparent as possible. By consciously counteracting the urge to dramatise, I can create a surface where the viewer does not encounter me, but encounters the wondrous and autonomous existence of non-human life”.

The photograph has long been associated with evidence, witness, and the authority of the real, yet your practice foregrounds interpretation and the constructed mood of the image. How do you want your work to be situated within the broader historical tensions between documentary and art photography, and what responsibilities do you think the photographer carries today when photographic images circulate as both aesthetic objects and cultural assertions?

Historically, photography has served as proof that ‘this happened.’ In my practice, I tend toward a phenomenological truth—how a place or an encounter felt, rather than exactly how its atoms were arranged at the moment of exposure.

Placement: I place my work in a field of tension where the documentary basis serves as a skeleton, while the artistic interpretation constitutes the body and nervous system. It is a form of ‘subjective documentary’ where the atmosphere is the actual testimony.

Tradition: I feel an affinity with the pictorialist tradition that dared to see photography as a craft on a par with painting, but with the sharp precision of modern technology as an anchor in reality.

The image as a cultural statement

When an image circulates today, it is never just an aesthetic object; it is a carrier of values and statements about our world. As a photographer, I believe that my responsibility has shifted:

Transparency over objectivity: Since we know that no image is objective, the responsibility lies in being clear about one's perspective. By emphasising the constructed atmosphere, I am honest about the fact that this is my perception, rather than hiding behind a false mask of ‘neutral’ observation.

Ethical aesthetics: When photographing environments or ways of life that are under pressure, aesthetic processing entails a responsibility not to gloss over problems into passivity, but to use beauty to create empathy and presence.

Viewer trust in a post-truth era

At a time when the photographic image is undergoing an ontological crisis (e.g. through AI and deep manipulation), the photographer's responsibility becomes to manage viewer trust.

‘My responsibility is not to deliver an exact copy of reality, but to deliver an honest interpretation of my presence in it.’

By allowing the image to be a clearly formatted expression, I invite the viewer to be aware that seeing is always an active act. I want my work to remind us that reality is something we participate in, not just passively register.

Your language repeatedly returns to “feeling,” “expression,” and “atmosphere,” implying that the photograph’s success is tied to affective precision rather than descriptive completeness. How do you evaluate whether an atmosphere is truthful, not to the factual scene, but to the experience you are staging for the viewer? What criteria guide your decisions when emotional clarity conflicts with optical neutrality?

For me, assessing whether an atmosphere is ‘truthful’ is not about matching pixels to raw data from reality, but about matching the final tone of the image to the core of the experience I want to convey. It is a question of internal coherence rather than external similarity.

Truthfulness as ‘Emotional Resonance’

I judge the atmosphere based on how well the staged experience resonates with the original encounter. If the scene in reality was marked by an overwhelming loneliness, an optically neutral image (with all the details in the shadows visible) is, paradoxically, a lie, because it does not convey that limiting, enveloping emptiness.

The criterion: If I can return to the image after a week and feel the same instinctive response I did on site, then the atmosphere is true to the experience.

When emotional clarity wins over optical neutrality

When choosing between showing ‘everything’ (optical neutrality) and showing ‘the right thing’ (emotional clarity), I choose the latter by using visual hierarchy. Optical neutrality is often democratic in a way that confuses the eye; it gives the same weight to an unimportant stone in the corner as to the play of light in the centre of the motif.

My decisions are guided by the following criteria:

The principle of subtraction: What can I remove (through blackening, blurring or colour toning) to reinforce the central feeling? The less noise, the clearer the emotional signal.

Colour psychology logic: If a neutral white balance makes the scene sterile, but a warmer/colder tone evokes the actual mood (e.g. oppressive heat or biting cold), the ‘incorrect’ colour temperature is technically more accurate in its communication.

Density of the atmosphere: I look for ‘density’ in the image. An image that feels airy and descriptive can lack weight. By manipulating contrast and luminance, I create a resistance in the image that forces the viewer to pause and feel rather than just read.

The boundary with the theatrical

The challenge is to avoid the atmosphere becoming a cliché or an empty decoration. To ensure that the staging does not become false, it must always be anchored in the subject's own conditions. I reinforce what is already there – I do not invent anything that lacks foundation in the character of the place.

‘Optical neutrality informs the brain, but emotional clarity speaks directly to the nervous system. My goal is for the viewer not only to see what I saw, but to feel what I felt.’

Across painting, colorizing black and white photographs, and contemporary RAW-based workflows, your practice seems to insist that image making is always a negotiation with history and technique. If we consider your photographs as part of a longer continuum of pictorial strategies, what do you believe photography can do now that painting once claimed as its territory, and conversely, what does your painterly approach reveal about photography’s limitations, its dependencies, and the philosophical stakes of insisting on the photograph as an authored image rather than a found one?

My practice is based on the insight that an image is never a passive reflection, but always the result of a series of choices – technical, historical and personal. By combining the subjectivity of painting with the source material of photography, I attempt to explore the image as a continuum rather than an isolated event.

What photography has ‘taken over’ from painting

Today, photography, especially through digital post-processing, has taken over painting's ability to create mythological and existential spaces. Where painting was once the only way to visualise the sublime, the dreamt or the ideal, photography can now claim the same territory – but with a unique advantage: the authority of reality.

Photography's claim: It can create atmospheres that feel as rich and composed as a classic oil painting, but with an underlying tone of ‘this has actually existed’. This gives the existential expression a weight that painting sometimes lacks in a secularised world; we believe in photography on an almost instinctive level.

What the painterly reveals about the limitations of photography

My painterly approach – colouring, enhancing and sculpting the light in the RAW file – acts as a critique of ‘pure’ photography. It reveals the limitation of photography: its tendency to be overly literal.

Dependence on chance: Photography often depends on what happens to be in front of the lens. By applying a painterly method, I demonstrate photography's inability to sift through the noise of reality on its own to arrive at an essence.

From ‘found’ to “created”: When I insist on photography as a created image, I acknowledge that the camera only provides the raw material. The limitation lies in the fact that pure photography often remains on the surface; by ‘painting’ in the image, I can penetrate beneath the surface and direct the viewer's gaze towards the underlying theme.

The philosophical implications

Insisting on photography as a created image rather than a found one is a stance against the idea of objectivity. It is a philosophical act that puts humans before machines.

Responsibility: If the image is found, I am merely a witness. If the image is created, I am responsible for its claim.

Historical connection: By colourising black-and-white photographs or working with historical techniques in a modern environment, I create a temporal collision. It reminds us that seeing is always coloured by the time and technology we live in.

‘By treating the photograph as a painting, I break its closed nature as evidence and open it up as a surface for reflection.’

The story behind Three glowing mushrooms:

In the silent forest stood three glowing mushrooms: Eldlys, the tallest and wisest; Tvillja, who could hear the whispers of the forest; and Lumen, the youngest with a still faint but pure glow.

One night, the Shadow Mist rolled in – a fog that dimmed all light and made the forest tremble. Eldlys raised her warm glow, Tvillja followed suit, but the fog continued to approach.

Lumen hesitated. Her light was barely visible. But when she saw how the others were struggling, she took courage, stretched higher and let her little glow grow.

When their three lights met, they formed a strong golden glow that cut straight through the darkness. The shadow mist receded and the forest breathed again.

From that night on, the three were called the Light Bearers, showing that even the smallest light can change everything when it joins with others.

The story behind The ”Misty port” and ”Evil women”

Deep within the whispering forest of Elowen Grove, where time drifts like mist and the air buzzes with ancient magic, stand the glowing mushrooms. These are no ordinary mushrooms—they are known as Lantern Caps, living torches lit by the forgotten spells of the forest spirits. These mushrooms are said to mark the entrance to the Fae Realm, a hidden world where dreams and light dance in harmony.

Legends tell of a forest guardian, a creature named Sylra, who protects the Forest Hats. Only those with kind hearts and quiet footsteps can catch a glimpse of her, flitting through the forest like a streak of moonlight. If a traveler finds one of the mushrooms and makes a wish by touching its glowing stem, the forest may grant them a single truth—or a secret long buried by time.

To enter Elowen Grove, you must pass through the right gate. There are gates to both the good world of Elowen Grove and the evil world of Ebonfern Forest, where silver mist clings to the earth like a whispered memory. The only way to find the right gate is to connect with the sun fairies who can guide you there.

Bridge in moon light

Bridge in sunset

Central station Göteborg

Evil woman

Gothia Tower

Ice

Light in the forest

Misty port

Oscar Fredric church

Sunrise Byklevsfallet

The sea goddess and sunset

Three glowing mushrooms

Welcome to hell

Zipper