Interview with Stefan Fransson

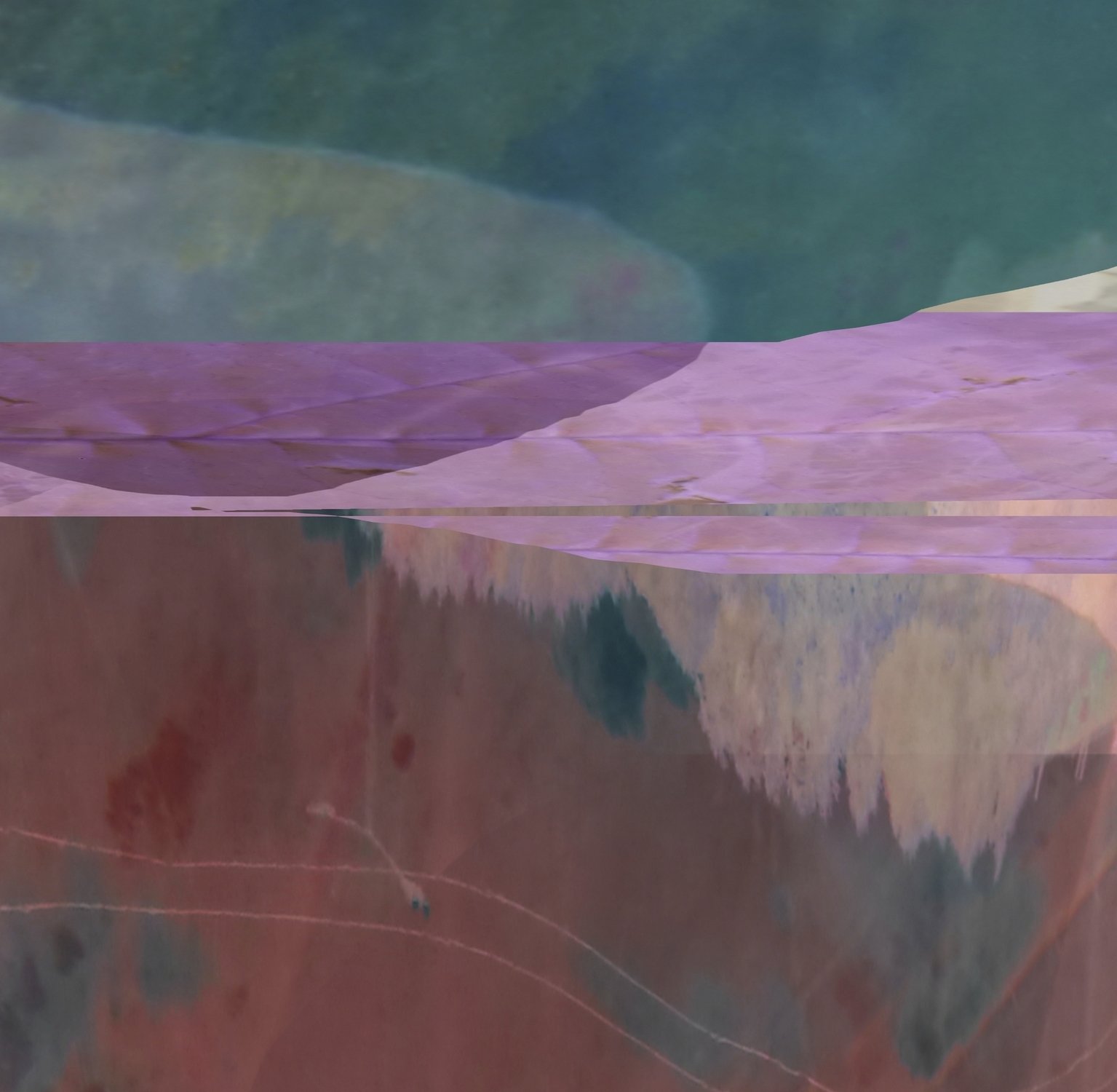

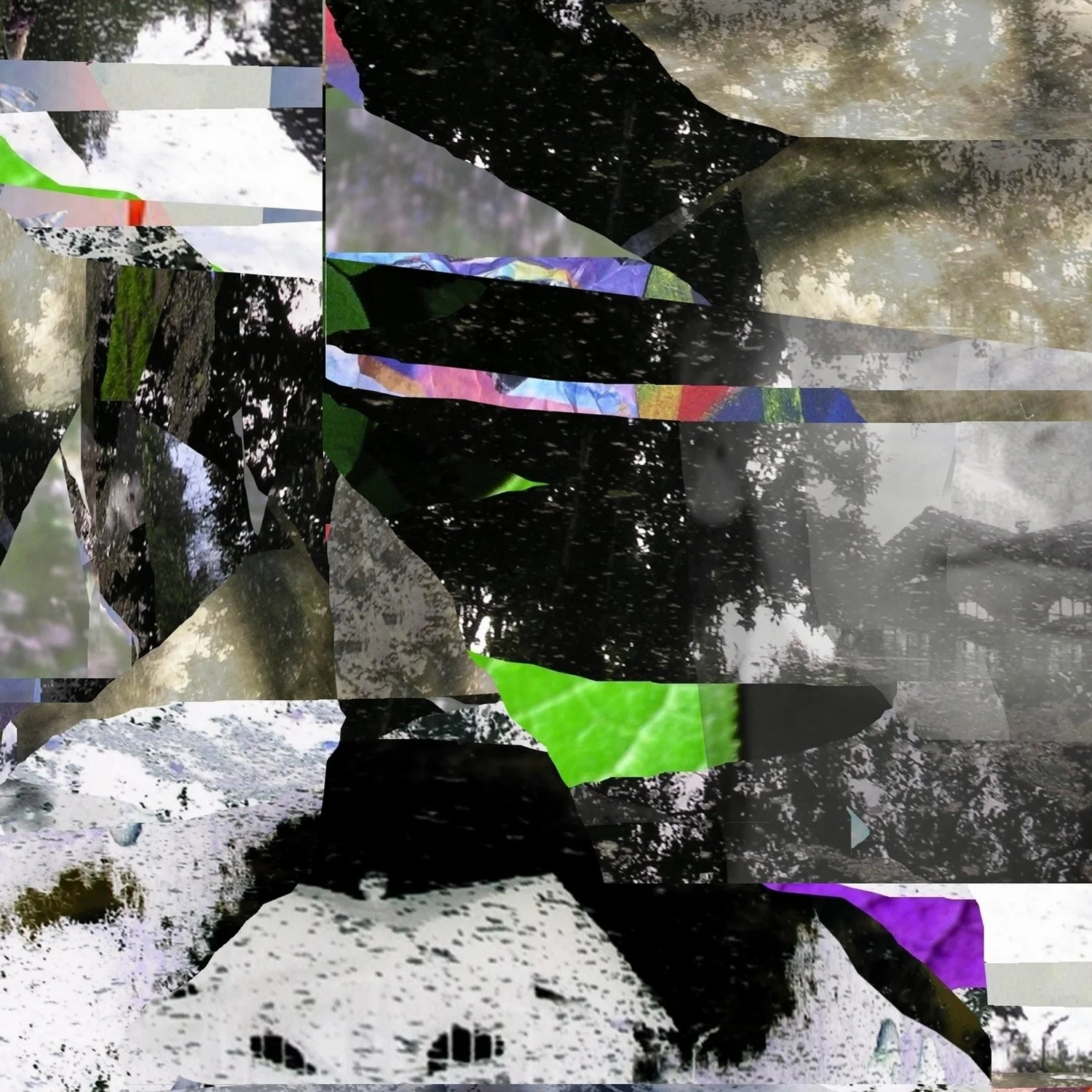

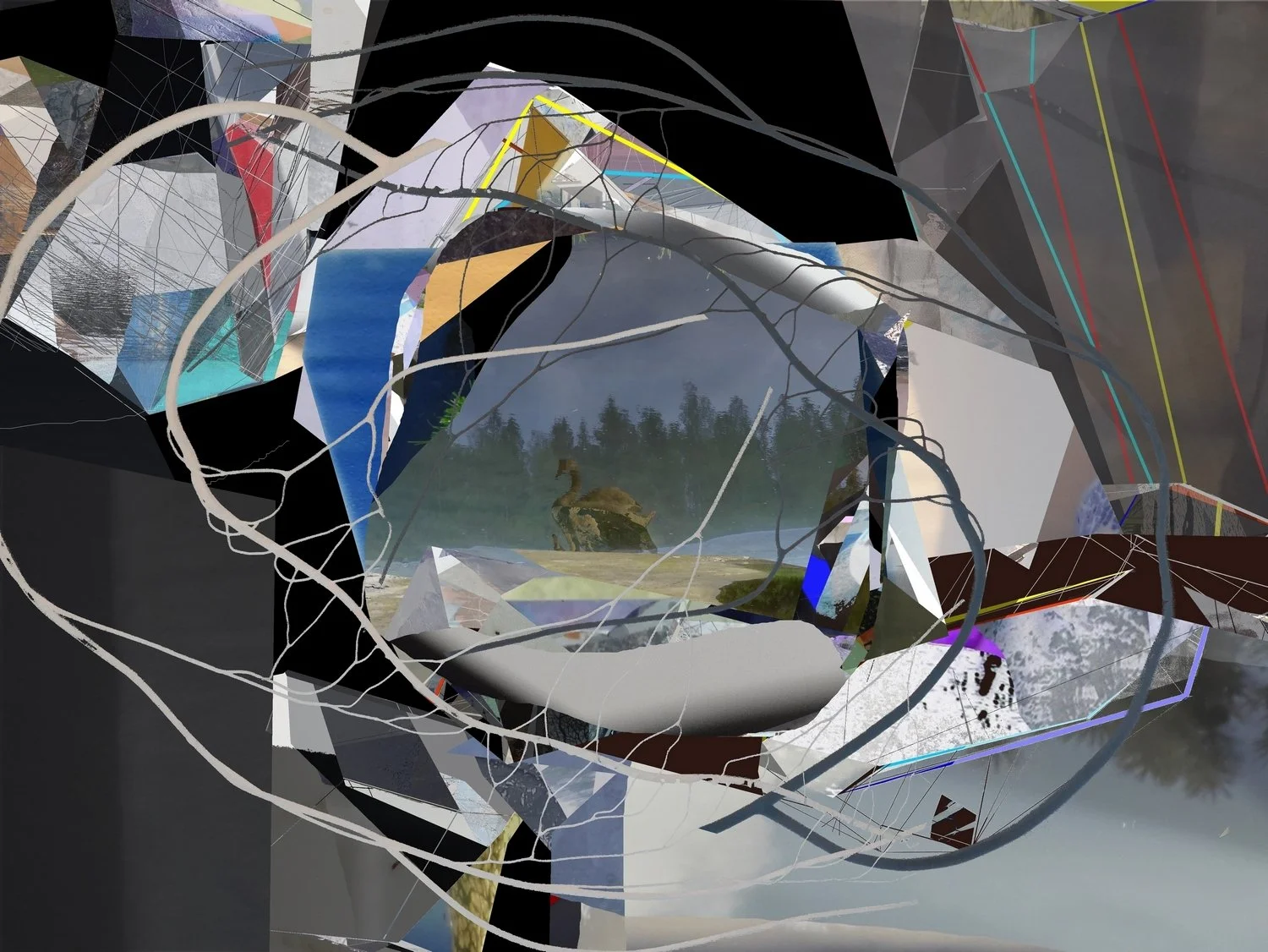

Stefan Fransson is a Swedish contemporary artist who blends digital collage, sculpture, and organic forms to create layered images. He combines soft tones with sharp contrasts, adding transparency and depth to each composition. His art often features geometric fragments and natural textures that form complex visual structures—through which he explores space, memory, and perception.

Stefan, your work persistently navigates the unstable border between the digital and the tactile, inhabiting what might be described as a “post-medium condition” in Krauss’s sense. In merging printed digital collage, scissor-cut interventions, and later analog re-assemblies, how conscious are you of performing a critique of medium specificity itself? To what extent is this hybridization an intentional destabilization of traditional artistic taxonomies, and to what extent is it simply where your own perceptual logic naturally leads?

My approach to creating images is deeply rooted in my perceptual logic, emphasizing intuitive exploration rather than conscious critique of mediums. My primary goal is to make images that communicate through the visual language, with a particular focus on composition, which fuels my experimentation with various techniques. This spontaneous mixing of elements, driven by my natural perceptual tendencies, results in my personal artistic expression.

So much of your practice contends with landscape not as representation, but as a psychological topology, a palimpsest of memory. Could you expand on how these landscapes function within your visual system? Are they mnemonic structures, phenomenological fields, or something closer to internal cartographies where perception and recollection collapse into a single temporal plane?

I hope that my landscapes function as complex internal cartographies that transcend mere representation, and function as mnes that reflect the fluidity of psychological and emotional states, merging time and space into a single, layered timeline. In my practice, the landscapes function as palimpsests of memory, with each layer revealing traces of memories, dreams, and subconscious impressions, blurring the boundaries between external perception and internal experience, ultimately creating a visceral, introspective visual system that hopefully explores the depths of human consciousness.

The answer to the question is that it is something closer to intenal cartographes where perception and recolation collapse into a single temporal plane..

Your sculptural works often operate like spatial drawings, gestures suspended in three-dimensional form, executed with minimal tools to preserve immediacy. How do you conceptualize “gesture” within your practice? Is it a residue of bodily movement, a notation of temporal intensity, or a means of installing the body within the work without literal representation?

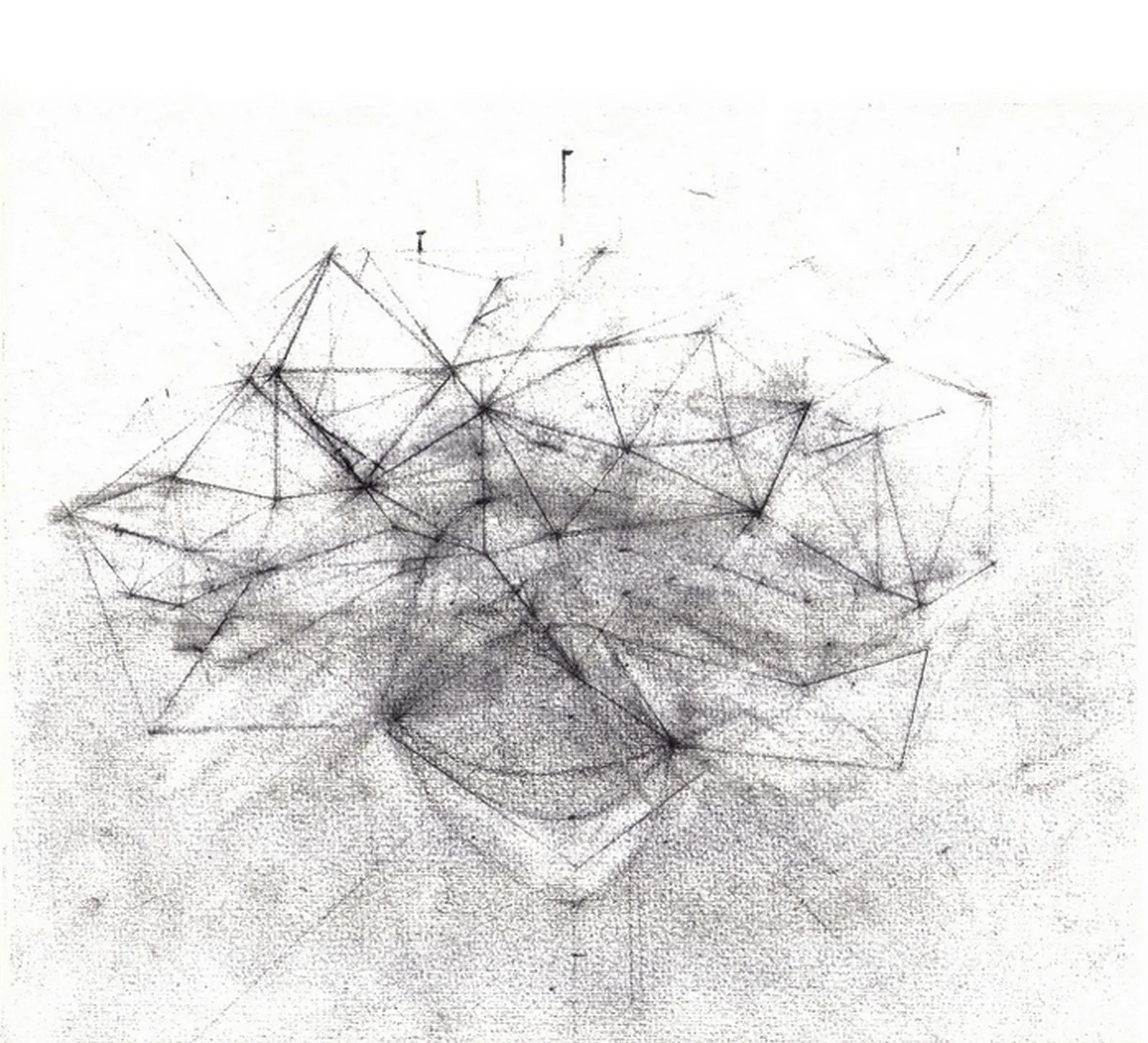

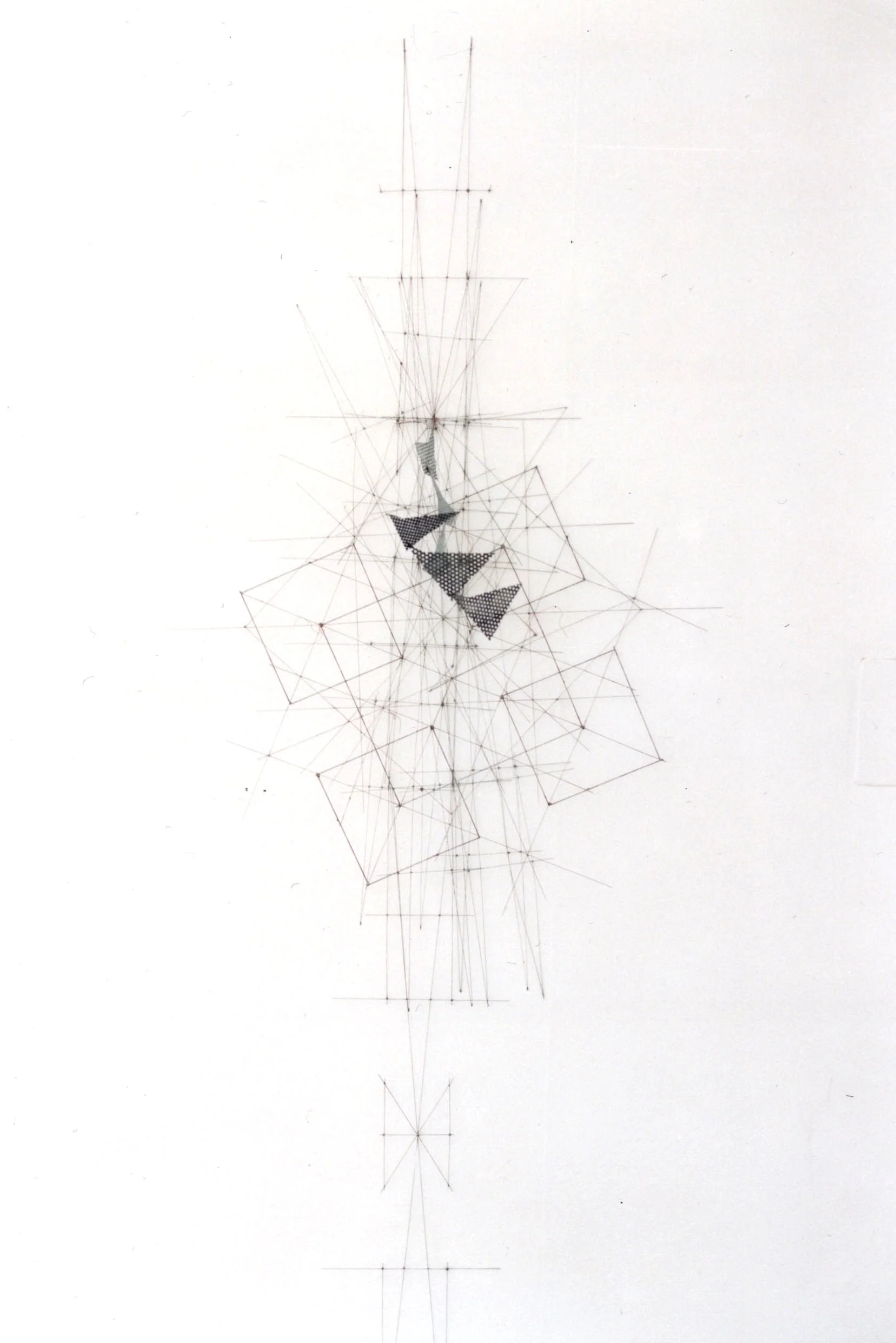

I think that it is a way of installing the body in the work without literal representation.The forms are rooted in my experiences of drawing. I have drawn the human body, trees, and other plants. I have also worked with the latter as geometry, for example when constructing and studying organic forms. In the drawing Geometric Drawing, there is an abstracted tree in the background. The tree recedes and the geometric forms took over.

That drawing was made a long time ago, it was close to my master’s degree. I had no studio for a couple of years, so my kitchen table was my studio. It felt natural for me to work with drawing during that time, and being limited by the surface of the table was actually something good. I did a series of drawings inspired by Fibonacci's number sequence. Using threads and air as material started already in my school days. When I later got a studio, I continued with the theme as sculptural compositions situated in given spaces. The, movement became something important, and it was gathered into a gesture

The notion of “flow,” which you describe as central to your process, suggests an altered state of consciousness where intention dissolves into intuitive operations. How do you negotiate the paradox between this intuitive, almost primal immediacy and the complex, layered, highly constructed nature of your finished pieces, particularly your digitally generated collages, which appear algorithmic yet remain deeply human in their perceptual logic?

To me, flow is a result of concentration. You have to work for it. It starts when I have worked for a while. Maybe I find something that I can develop further. It usually has to do with spatial things. When I am in flow, everything merges, and then I see nothing paradoxical. Constructive thinking and intuitive thinking become the same thing, impossible to separate. All you want is to create an image that is whole. Personally, I see it as layers of images that might be hidden somewhere in my mind. What I need to do is let them float up to the surface, just to see if they fit in this situation, if they fit and build on what is already there; it could be a piece of a construction that is irrationally scattered, perhaps applied transparently.

Your collages contain geometric shards, transparencies, and overlapping strata that appear to oscillate between fragmentation and coherence. In viewing them, one often senses a kind of structural entropy attempting to resolve itself. Do you consider these works as self-organizing systems, visual ecosystems that expose the mechanics of their own assembly, or are they closer to psychological diagrams, mapping the tension between order and dispersal?

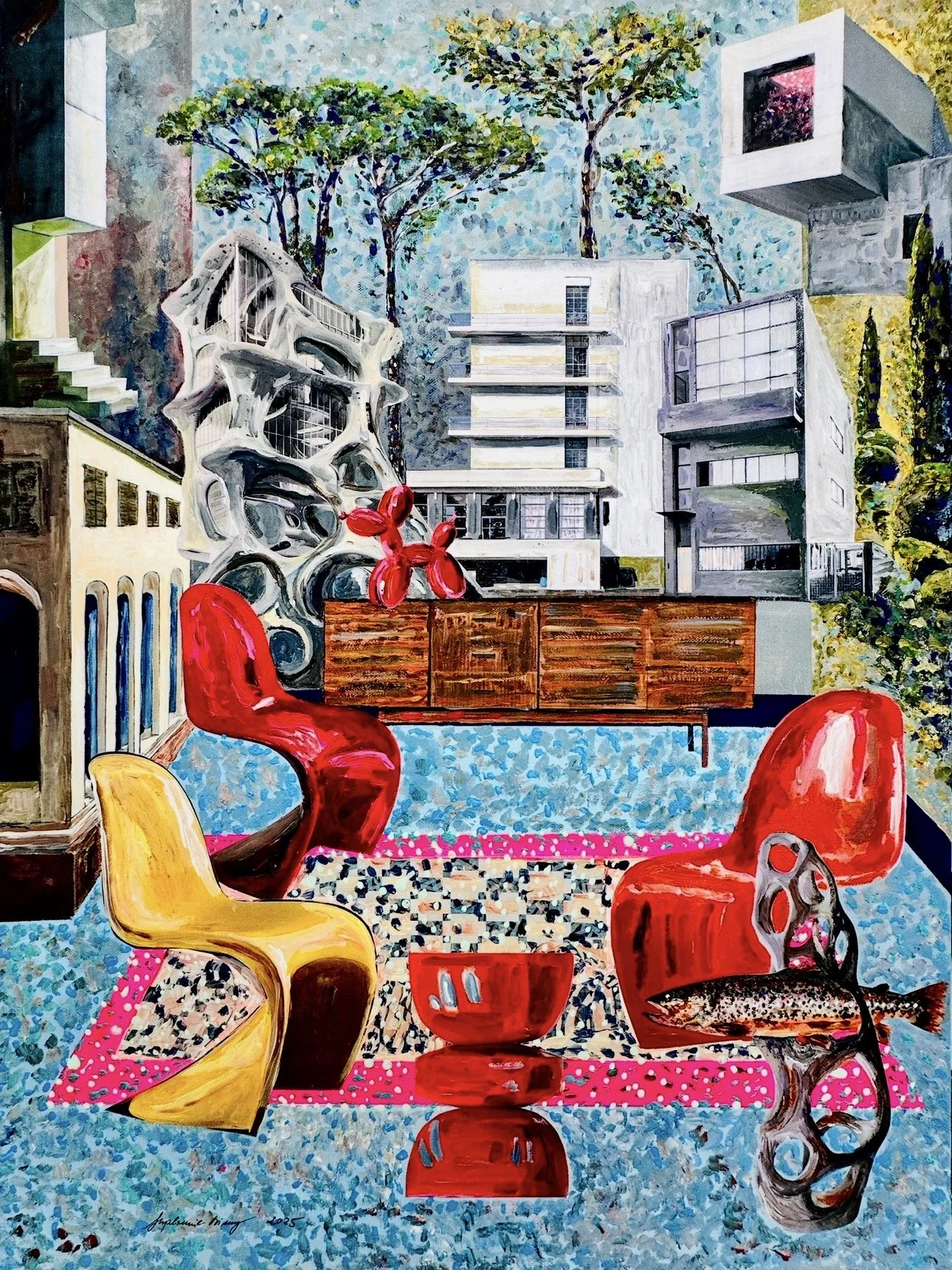

My work explores the tension between fragmentation and coherence, aiming to achieve a sense of wholeness despite contradictions. My images, often complex, feel complete when they hover on the edge of order without becoming overworked, and when they still feel open. The digital process allows me to reach a state of flow, hopefully resulting in images with visual poetry that others can perceive, while my hybrid work introduces a slower process, often taking place on the floor. The collages, digital or analog, reflect psychological landscapes and embody a tension between order and dispersal.

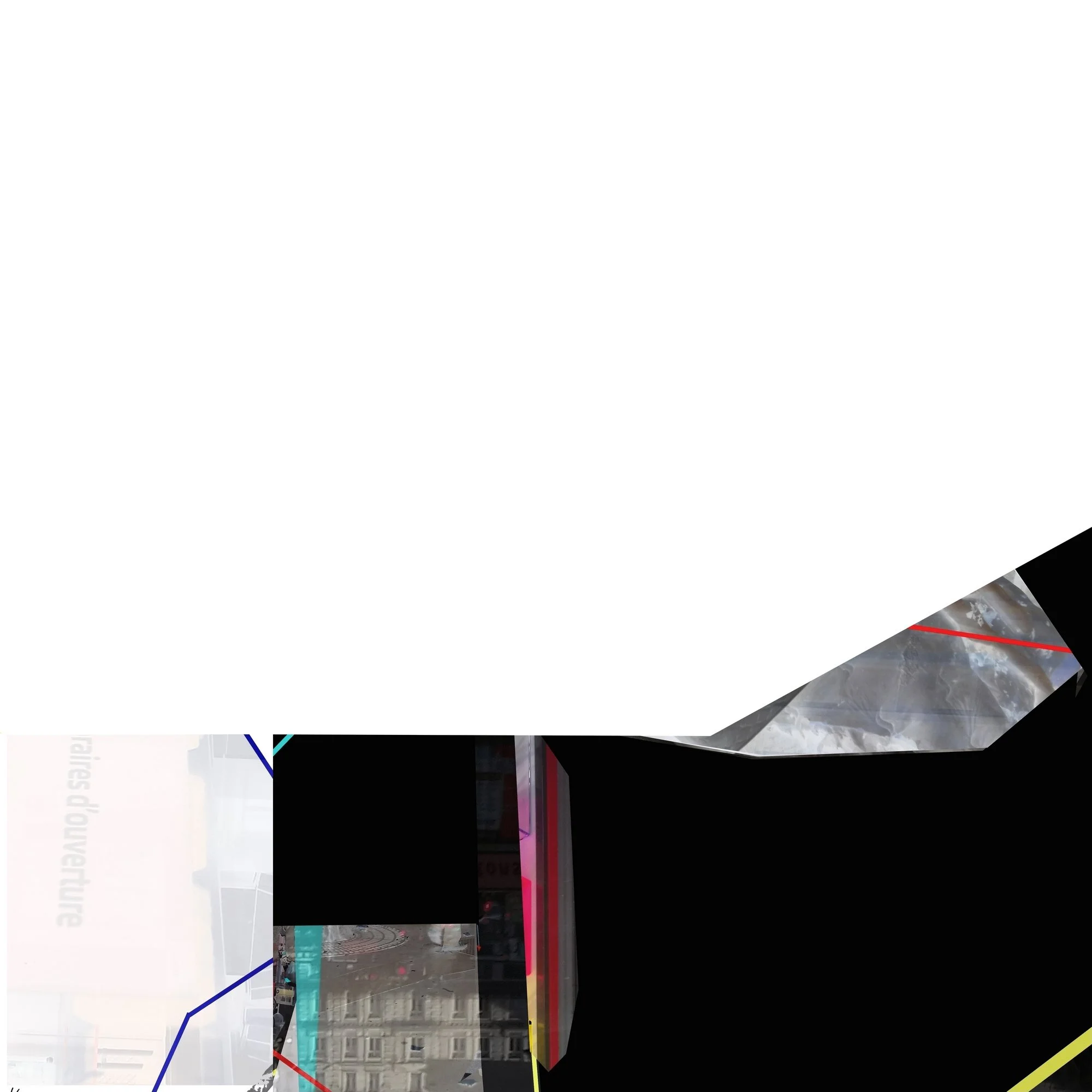

Having worked nomadically, often with only a laptop as your primary tool, your practice has internalized a certain mobility, images collected and recomposed across geographies. How do you understand the role of displacement and travel in shaping your visual language? Is the studio still a fixed locus of creation for you, or has “studio” become a distributed condition embedded in the rhythms of movement, environment, and digital capture?

The period when I traveled with my laptop was very interesting. The light and architecture of the new place inspired me. The reason I traveled was precisely this constant change. After three years of traveling, however, I began to long for a studio, just to be able to work in a more analog way. After that, I went home to Stockholm because I had the opportunity to rent a studio, and that’s where I began working on my hybrids. I still travel quite a bit, and I always bring my laptop to use as a studio. I have now acquired a studio outside Stockholm where I go to work more analogically, but I would probably say that the studio is embedded in the rhythms of creative movement, where the digital follows and inspieres, as I always have a laptop to work on.

Your analog-digital hybrids resist the binary between the mechanical and the handmade. This fusion echoes the post-surrealist experimentations of artists who questioned the neutrality of photographic imagery. How do you position photography within your own practice? Is it an evidentiary trace, a raw material to be violated and reconfigured, or a mechanism for collapsing temporalities into a single visual instant?

For me, it’s probably mostly about my photos being temporalities into a single visual moment. Maybe there’s a built-in critique of the medium, though. It probably has more to do with the fact that I’m no expert in photography. I remember my first camera and the disappointment of my first photos. All the images from the long-awaited development were so flat, and therefore so uninteresting. I think that experience remains somewhere in my subconscious, and that through my collage technique I try to recreate the depth.

The interplay of transparency, opacity, and layered spatiality in your compositions evokes a kind of architectural thinking, yet one deeply tied to memory rather than construction. Could you discuss whether your work attempts to create spatial metaphors for cognitive states? Do these layered structures operate as containers for perception, or as disruptions of coherent spatial logic?

My work truly explores the interplay between transparency, opacity, and layers upon layers of spatiality, creating compositions that resemble architectural metaphors filled with memories rather than physical construction. The layered structures function as visual containers for perception, inviting the viewer to explore the complexity of cognitive states, where memory and emotion coexist in fragmented, overlapping spaces. These structures often challenge traditional notions of coherent spatial logic and function more as disruptions that reflect the fluid, non-linear nature of human consciousness. Through this, my art encourages reflection on how we perceive, remember, and emotionally inhabit spaces, blurring the boundaries between external architecture and internal mental landscapes.

Your biography reveals long periods of pedagogical engagement, especially at Konstfack, where you shaped discourse around drawing, sculpture, and spatial design. How has the act of teaching informed (or perhaps complicated) your own artistic ethos, particularly your resistance to rigid frameworks? Has pedagogy contributed to the expansion of your practice, or has it functioned as a counter-pressure that clarified your commitment to intuition?

My decision to step back from teaching at Konstfack has been a positive move, allowing me to focus on my personal studio work and embrace a sense of freedom and creative fulfillment. My experience of adapting teaching methods to meet the individual needs of students amid the school's transformation left increasingly less time for my own studio work. Going forward, this change seems to give me the opportunity to deepen my own artistic practice, which can be enormously rewarding both personally and professionally.

Much of your work seems preoccupied with what remains after an image disappears: the after-image, the perceptual echo, the residual imprint on consciousness. Given your statement about images “staying in the consciousness and melding with the present,” how do you conceive of temporality in your practice? Are your works attempts to capture the simultaneity of perception where past, present, and the nearly-past coexist, or are they constructing a new temporal grammar altogether, one that resists linearity in favor of experiential depth.

My work explores the fluid nature of temporality by emphasizing the enduring presence of images in consciousness, suggesting a perception in which past and present are seamlessly intertwined. My artistic practice is not merely aimed at capturing a moment, but rather at evoking the experience of simultaneity, where afterimages and perceptual echoes create a layer of experiential depth that transcends linear time. Through this, I construct a new temporal grammar altogether, one that resists linearity in favor of experiential depth.