Interview with Eva Nordholt

Eva, in your paintings, flowers crowd the surface with a kind of insistent presence, neither ornamental nor merely symbolic, but almost structural. How do you conceive of botanical form as an architecture of the image, a scaffolding that can both support and threaten to overwhelm the figures within it, and what does this tension tell you about the unstable line between beauty and claustrophobia?

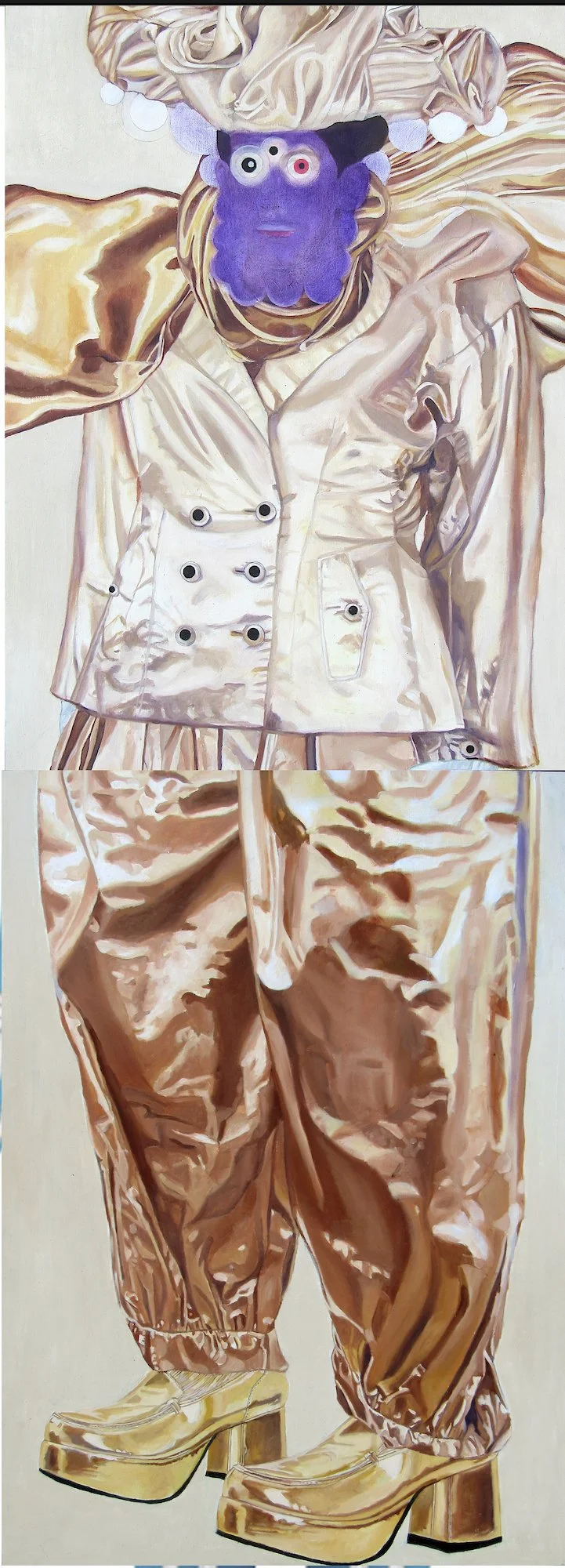

I like that you mention the unstable, or fine, line between beauty and claustrophobia. Making the flowers the sole object of the painting or too beautiful, could well make the painting indeed claustrophobic or simply boring. It needs a dissonant to make it interesting in my opinion. The competition between the gold clothing of the figures and the flowers is an effort to create the tension you mention, so you could say that the flowers indeed threaten the figures, or at least the figures feel threatened by them.

Gold appears throughout your work not as a simple sign of glamour, but as a material laden with ambiguity, radiance and sorrow. When you paint gold, do you think of it as a skin, a surface, a shield, or a wound? How do you negotiate the emotional paradox of something dazzling that simultaneously carries a sense of melancholy, and what happens to the figure who wears it?

The gold could well be an armor hiding a wound, but for most of the figures who wear it it probably feels like an enrichment of their appearance, wherein lies the sadness for me. It may go back to an experience I had as a small child, when I was over the moon with a beautiful, blue cotton dress that was embroidered at the hem with small flowers. I remember being so happy with it that it sent me into a state of sadness, because I realized it was temporary and I would soon be too big to be wearing it. I realized at that time that life would be like that, an endless cycle of striving, realizing and losing.

The reflective fabrics in your paintings, such as silk, vinyl and metallic textures, feel almost alive, less clothing than membranes. They mask and reveal, they protect and expose. How does the act of rendering the surface itself become psychological content, and how do you think about the intimate relationship between surface and depth when constructing a figure?

While painting the gold, I enjoy it's beauty and the technique I use. I experiment with different colors, in the gold or silver and in the shadows, because the standards are never set. This is the technical part on which I focus, compartmentalized is the connotation of sadness and melancholy. It is an intuitive process rather than something planned or thought out, and it changes as the painting progresses. The figures surely feel protected, but in a certain way are exposed at the same time because you can't help but wondering what lies underneath, which is the relationship between surface and depth.

Many of your compositions place figures in direct conversation with the vegetal world. They stand among oversized blossoms, luminous berries or impossible forests. These encounters are not pastoral but theatrical, sometimes unsettling. Do you imagine these environments as extensions of internal states, as protagonists in their own right, or as witnesses to the figures they surround? What kind of narrative emerges from this mutual observation?

I would say that the vegetal world represents a longing, a fruit, to use a cliché, that is hanging low but out of reach. That may well be the reason the figures are trying to compete with it, maybe in an effort to merge with it. So what you see is an interaction and an extension of an internal state, witnessed by the vegetal world.

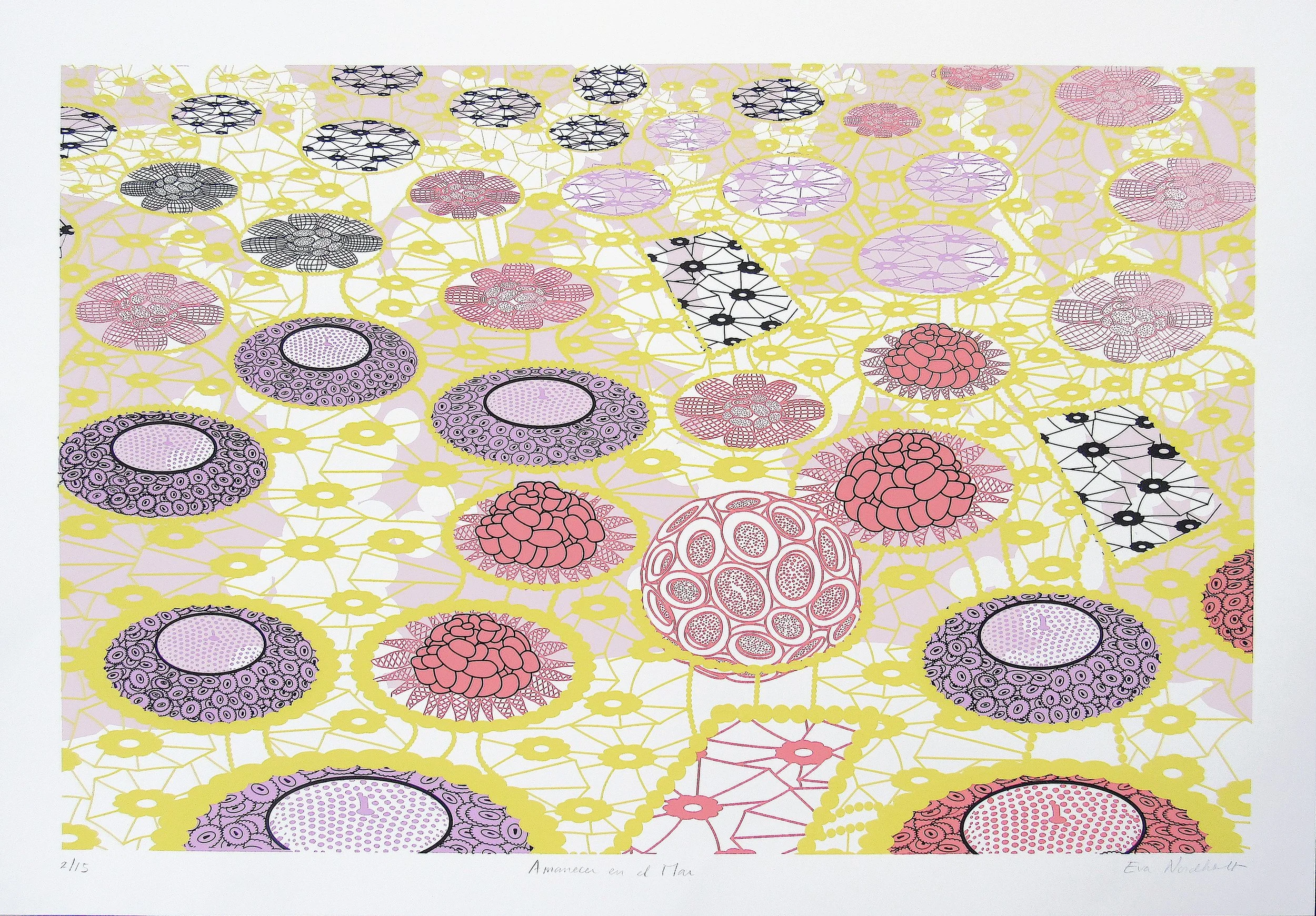

Your biography moves through graphic design, early computer drawing, photography, animation and finally to oil painting and silkscreen. Rather than a linear progression, it reads as a circular return. How does your early training in digital tools and image systems continue to influence your painting practice, especially in terms of composition, layering and the tension between precision and intuition?

It does not influence my painting practice very much directly, allthough I do design parts in Photoshop. Once I'm painting the design is just the basis, from there on it is intuition, brush stroke and experience that are important. I am still very much interested in graphic design and photography, so different types of imagery influence my work at many levels, consciously and subconsciously. The silkscreens are definitely a part where my experience with graphic design, painting and digital tools come toghether. They are in fact stylized images of plancton, (creatures that live in the sea but are invisible to the naked eye). I take a lot of poetic license in creating an imaginary natural yet abstract seaworld with them. Those designs in turn influence my paintings.

In your series that depicts women and children turned away from the viewer, with faces obscured or hidden, there is a strong sense of interiority. These figures seem absorbed in their own worlds, neither offering themselves to us nor actively refusing us. What interests you about this withholding? Is the gesture of turning away an act of protection, defiance or introspection, and how does it shape the viewer’s emotional experience?

I have no way of knowing how it influences the viewer's experience, they might feel shut out, or they might feel intrigued, but I think that is what makes the painting interesting. What interests me in painting them like that is that I myself don't know what is going on in their minds. They very quickly become their own beings, I imagine it is like writing a character in a novel, and I myself can only guess what is going on, what they are seeing, what the expression on their faces is like or even what their faces look like.

You have spoken of gold as carrying sadness, and of flowers as repositories of endless fascination. This coupling suggests a poetics of attraction and loss. When the lushness of the painted surface becomes almost excessive, does excess itself become a subject? What is the emotional edge of abundance, and how do you maintain balance between seduction and unease?

I think it does become it's own subject. The emotional edge of abundance cannot be anything other in my mind than emptiness and loss, the exact opposite, it simply becomes too much to bear.

You often rework older paintings, layering new realities over previous intentions. This process carries a sense of sediment and archaeology. What happens to memory when one painting overwrites another? Do you think of revision as erasure, transformation or dialogue with a former self, and how do you know when a work has reached its final state rather than a temporary pause?

The practical answer is that I made the early paintings to teach myself how to paint. You know they are not very good, technically mostly, but you trick yourself that they are in order to be able to go on. After not seeing them for a couple of years, it is interesting to see them with new eyes and realize what you could have done better, you immediately see what you could add or change and it's actually a fun process. So it is mostly about transformation, transforming a perhaps somehwat dull and stiff subject into one that has more experience and layers. At some point it is finished because you know it is not yours anymore. It has become a given, good or bad, and you can't neghotiate with that.

Living and working in a forest outside Barcelona, your daily practice is marked by light, temperature and the rhythm of the seasons. To what extent does the forest infiltrate your paintings, not only as a motif but as a temporal structure such as slow growth, cycles of decay and return? How do you perceive time when you are painting, and do you experience the studio as a kind of ecosystem?

It is definitely stimulating to work outside, and it makes you concentrate better. I work outside until it gets too cold, around November/December. While painting you are slightly aware of the sounds and sensations around you, like the wind, rain, animals scurrying about, insects buzzing, birds singing. When the heat sets in here in Spain I use an electrical fan, whose humming sound together with the summer crickets puts you in yet another realm. Time doesn't really exist when you paint, a day goes by in a heartbeat or so it seems.

In your recent reflections, you mention gilded people and a possible family as your next subject. Families tend to be both mythic and intimate, simultaneously idealised and fragile. What does the act of gilding do to the idea of kinship? Does it monumentalize, preserve or complicate it? And in envisioning this project, are you imagining a portrait of a family as they are, as they remember themselves, or as they wish to be seen?

If I painted a gilded family, they would look superficially similar to the viewer due to their clothes. It is probably their goal to create an image of unity. So it is a lot about appearance, and about hiding what lies underneath.

Sisters, oil on wood, 60x50 Eva Nordholt

Daffodils,oil on wood, 50x70',Eva Nordholt

The shadow,oil on wood, 100x100_ Eva Nordholt

The white shadow,oil on wood, 100x100, Eva Nordholt

The rabbit,oil on wood, 120 x 180, Eva Nordholt

The conversation,oil on canvas, 81 x 115, Eva Nordholt

The tribute,oil on wood, 100x 81, _Eva Nordholt

Angels_oil on wood, 100x 81,Eva Nordholt

Jabalies_oil on wood, 100x81,Eva Nordholt

The gilded man_Eva Nordholt

Dawn at sea, silkscreen, 9o x 60 cm, Eva Nordholt

Plancton pond, silkscfreen, 60 x 90, Eva N ordholt