Interview with Souad Haddad

Souad, your practice frequently mobilizes the flower as both a formal device and a conceptual premise, echoing your childhood garden in Lebanon yet transmuted through impasto into sites of density, resistance, and insistence. How do you negotiate the tension between the flower as a historically sentimentalized motif in Western painting and your impulse to reconstruct it as a signifier of resilience, feminine agency, and psychological fortitude? In other words, what operations must the flower undergo in your studio to shed nostalgia and become a structural proposition about contemporary womanhood?

The flower in my work is a site of transformation. In the studio, I apply acrylic to build the flower into a dense, almost tactile structure, disrupting its softness. This process is an act of resistance: I flatten the flower’s historical associations with fragility and sentimentality, replacing them with a materiality that speaks of endurance.

The flower becomes a symbol of resilience not through its original meaning, but through its reconfiguration. I layer paint, build texture, and distort form to make it a structure—something that holds, that insists. The act of making is itself a reclamation. The flower is no longer a relic of the past but a present, active force. It is a signifier of feminine agency because it is built, not given. It is a testament to psychological fortitude because it is made to endure, to resist and to stand.

In this way, the flower is not shed of nostalgia—it is transformed into a new language, one that speaks to the contemporary woman: strong, complex, and unapologetically present.

Coming from a background in wealth management and capital markets, your daily professional life is saturated with systems of abstraction, risk, speculation, and value formation. To what extent does the logic of finance, its fluctuations, its algorithmic temporality, and its invisible architectures inform the way you construct pictorial space? Might we consider your thick, gestural surfaces as counter-structures to the immaterial world of finance or perhaps as parallel systems of coded information?

The logic of financial markets—its abstraction, risk, and value—resonates deeply in my work. My paintings, are built in layers of paint, texture, and gesture—physical acts that resist reduction to data. The impasto is a kind of resistance, a way of making the invisible visible, of grounding the abstract in materiality.

I see my work as a parallel system of coded information. The flowers, the forms, the textures—they are not just images but systems of meaning, built through labor, through repetition, through the body’s engagement with the canvas. They are a kind of financial metaphor: not in numbers, but in the way they accumulate, resist, and hold value in a different form.

In this way, my work is both a counter-structure to finance and a parallel system—one that operates in the realm of the tangible, the embodied, and the resistant.

Your paintings inhabit a visual lexicon of impasto, saturation, and chromatic exuberance, yet beneath this sensorial immediacy lies a subtle meditation on the negotiation between fragility and force, a dialectic you attribute to the women who raised you. How does your work articulate the coexistence of vulnerability and strength without collapsing into binary representation? What visual strategies allow you to articulate a specifically feminine ontology without surrendering to essentialism?

My work navigates vulnerability and strength through texture and contrast. The impasto is not just a material choice but a way to build tension—layered, dense, yet delicate in its construction. The saturation of color is not a sign of excess but a means to amplify the emotional weight of the image, to make the fragile visible and the force palpable.

The flowers are not simply soft or strong, but both at once—built with force, yet their forms are delicate, their edges ambiguous. This duality is not a contradiction but a coexistence, a way of honoring the women who raised me: their quiet resilience, their emotional depth, their ability to hold both fragility and strength in the same body.

It aligns with a feminine way of being that is not defined by a fixed identity but by the dynamic interplay of presence and absence, of touch and distance, of softness and force. The painting becomes a space where these tensions are not resolved but coexist, as they do in the women I grew up with.

The collections you have developed, Peonies, Mini Collection, Wishes, The Surface, Life Collection, each propose a distinct phenomenology of looking: from the surface as a site of rupture to the flower as an index of desire, memory, or futurity. How do you conceive of the “collection” as a structural logic in your practice? Does seriality function for you as repetition, variation, or a form of ritualized self-inquiry?

A collection is not a set of works but a structural logic of inquiry—repetition, variation, and ritual. Each series is a way of exploring a particular mode of looking, a way of engaging with the surface, the flower, the body, the memory.

Peonies is about the good old values and the unconditional love that was previously. It is a call to take the time to stop, breath and be grateful about the things we have in a busy life. Mini Collection is a series of small paintings reflecting our garden of life. Wishes is about desire as a kind of unfulfilled or unspoken longing, a visual index of what we wish to have in a world full of hatred. The Surface is about the act of looking beyond the surface, there are lots of details worth catching if we look deep into any surface. Life Collection is about the way life is both fragile and persistent, it shows vibrant colors beneath the monochromatic colors of life.

Seriality is not repetition but variation—each work in a collection is a different gesture, a different way of looking. It is a form of ritualized self-inquiry. The collection becomes a way of testing the limits of the motif, of pushing it beyond its original meaning. It is a way of asking: what happens when I look at a flower again? What happens when I look at a surface, a wish, a memory? The collection is not a conclusion but a process of ongoing questioning.

Your work often stages flowers in moments of what might be called “painterly emergence,” floating between figuration and abstraction, between botanical specificity and gestural excess. How do you think about the threshold where the image dissolves into pure materiality? Is there a conceptual importance in placing the viewer in a liminal zone, one in which recognition is constantly destabilized?

The threshold between image and materiality is where the painting becomes a site of becoming—where the flower is no longer just a subject but a process, a gesture, a texture. As I previously mentioned, the flower is not just painted but built, its form emerging through layers of acrylic.

The viewer is not looking at a fixed image but at a process in motion, a surface that is both there and not there. The flower is present, but its presence is mediated by the materiality of the paint—its texture, its weight, its resistance. This creates a tension between what is seen and what is felt, between the botanical and the gestural.

Conceptually, this is a way of engaging with the viewer as co-creator. The painting does not offer a clear answer or a fixed meaning. Instead, it invites the viewer to participate in the act of seeing, to question what is real, what is imagined, what is made. The flower is both a sign and a surface, a symbol and a material thing. In this space, recognition is constantly destabilized, and the viewer is left in a state of becoming.

Given that your artistic formation was entirely self-directed, your process sits outside the conventional academic lineage of art training. How has this autonomy shaped your relationship to technique, experimentation, and the history of painting? Do you feel that your self-taught trajectory affords a certain freedom from canonical pressure, or does it create a parallel responsibility to invent your own genealogy of influences?

My self-directed artistic formation has indeed shaped my relationship to technique, experimentation, and the history of painting in ways that are both liberating and demanding.

From the beginning, I was not bound by the rigid structures of academic training. I learned through observation, through the act of making, through the dialogue between the body and the material. This autonomy has given me a freedom to explore without the constraints of formal instruction, to experiment without the pressure of fitting into a particular tradition or style. I am not bound by the expectations of the canon, and this has allowed me to develop a practice that is both intuitive and deeply rooted in the physicality of painting.

Yet, this freedom also carries a responsibility. Without the scaffolding of formal training, I have had to build my own genealogy of influences—my own lineage of artistic thought and practice. I do not simply borrow from the past; I engage with it in a way that is both critical and creative. I am constantly questioning where I stand in relation to the history of painting, and how my work can contribute to or challenge that history.

In this way, my self-taught trajectory is not a rejection of the past, but a reclamation of it. I am not trying to invent a new language from nothing, but to find a voice that is both personal and historically situated. The act of painting becomes a kind of dialogue—between the self and the history, between the material and the conceptual, between the gesture and the idea.

So, yes, there is a certain freedom in being self-taught, but also a responsibility to create a lineage of my own. It is a delicate balance—one that I continue to navigate with both curiosity and humility.

The impasto technique you employ generates relief, shadow, and tactile presence, almost pushing the works into sculptural territory. How do you understand this material excess in relation to the history of the picture plane? Does the raised surface operate for you as a metaphor for psychological depth, as an interruption of opticality, or as a method for asserting the body of the painter, the female body within the very architecture of the canvas?

The impasto technique I use is a mode of engagement with the picture plane, a way of redefining its boundaries and its function.

In the history of painting, the picture plane has traditionally been a flat, two-dimensional surface, a window onto the world. But I am drawn to the idea of the picture plane as a site of becoming, a space where the materiality of the act of painting can intervene in the very structure of representation. Impasto, with its raised surfaces, shadows, and tactile presence, pushes the work beyond the flatness of the canvas, into a realm where the painting is no longer just seen but felt.

This material excess is, for me, a metaphor for psychological depth. The layers of paint, the texture, the weight of the surface—these are not just visual elements but emotional and psychological ones. The painting becomes a kind of interior landscape, a place where the viewer is not just looking but experiencing the presence of the subject, the gesture, the emotion.

It is also an interruption of opticality. The picture plane is not just a surface to be looked at; it is a space that resists being flattened. The impasto creates a kind of visual topography, a landscape of light and shadow that challenges the viewer’s perception. The painting is no longer a passive image but an active, embodied presence.

The texture, the gesture, the weight of the paint—these are all traces of the painter’s hand, of the body in motion. In this way, the painting becomes a site of embodied presence. So, in short, the impasto is not just a technique—it is a philosophy, a way of rethinking the picture plane as a site of material, emotional, and embodied presence. It is a way of making the painting not just a thing to look at, but a thing to feel, to touch, to be in.

Many of your works conjure an atmosphere of suspended temporality, flowers blooming outside natural cycles, chromatic intensities that exceed realism, and compositions that evoke memory more than observation. How do you conceive of time within your paintings? Are they anchored to biographical time, seasonal time, mythic time, or perhaps the therapeutic temporality you describe as the time of “flow,” which dissolves linear progression?

My works do not simply depict a moment in time—they conjure a time that is both real and imagined.

In my paintings, I think of time as a kind of atmosphere, a quality that lingers beyond the moment of seeing. The flowers that bloom outside natural cycles are not just botanical anomalies—they are metaphors for time that is not bound by the constraints of nature. They are reminders that time is not only what we experience, but also what we feel and remember.

The chromatic intensities in my work are not just visual but temporal, evoking a sense of memory, of feeling, of something that has been seen but sometimes never quite seen again. Sometimes they are the colors of a memory that is not just remembered but felt.

My compositions evoke memory and observation. I try to capture a moment as it feels not as it is. The painting becomes a place where the past is not just recalled but re-experienced. This is not a nostalgic time, but a time that is open, that is fluid, that is alive.

I do not anchor my work to biographical time, seasonal time, or mythic time in a literal sense. Instead, I am drawn to a kind of therapeutic temporality—a time that is not bound by the clock, that is not bound by the past or the future, but is instead a time of flow, of presence, of being.

This is the time of the painting itself. It is the time when the viewer is not looking at a moment in history, but at a moment that is alive, that is in the making, that is in the becoming. It is a time that is not just seen, but felt, remembered, and reimagined.

In this way, my paintings are not just about time—they are time itself.

Your paintings of women seem to operate not as portraits but as archetypes, carriers of an interiority that is both shared and deeply individual. In a moment where the politics of representation are heavily scrutinized, how do you navigate the ethical dimension of portraying femininity? What does empowerment look like when articulated through color, gesture, and form rather than through figuration in a literal sense?

My paintings of women are not portraits in the traditional sense, but rather embodiments of a kind of interiority—a space where the female body is not just represented, but reimagined, reclaimed, and reverberated. I do not seek to depict the female body as it is, but as it could be—as a space of possibility, of interiority.

Empowerment, for me, is not something that is shown in a literal sense, but felt through the language of color, gesture, and form. The female figure in my paintings is not a subject to be observed, but a subject in motion—a presence that is both visible and invisible. The color is not just a visual element, but a sensory experience that evokes a kind of emotional and psychological resonance. The gesture is not just a physical act, but a statement of presence, of being, of not being seen in the way that the world might want to see women.

I am trying to create a representation of the women that is not bound by the constraints of the literal, but by the intensity of the emotional and the depth of the psychological.

In this way, empowerment is not something that is achieved through figuration, but experienced through the act of seeing and feeling that is emotional, existential.

In navigating the ethical dimension of portraying femininity, I am not trying to avoid the politics of representation, but to reimagine them. I am trying to create a new kind of presence—a presence that is rather felt.

Your art has entered international exhibition circuits, earning recognition such as Artist to Watch 2024 and Top 60 Masters 2025. As your work moves into global visibility, how do you reconcile the intimate, autobiographical origins of your practice with the expectations of a transnational art market that often consumes “identity” as aesthetic capital? Do you see your role as an artist shifting as your work becomes part of broader cultural narratives?

My work begins in the intimate, the personal, and the embodied. It is rooted in the body, in memory, in the textures of feeling, in the rhythms of being. The figures I paint are not just representations of femininity or identity, but of experience—of the body in motion, of the mind in flux, of the self in relation to the world. They are not about “identity” as a fixed or commodified concept, but about being—the act of existing, of feeling.

But when my work enters the global art market, it is often reduced to a kind of identity capital—a shorthand for “feminine”. This is not always a bad thing. There is a risk that the personal can be flattened into a kind of aestheticized “identity” that is more about spectacle than substance. There is a danger that the work, which began as a deeply personal act, can become a product of the market, a commodity that is more about consumption than connection.

I do not see my role as an artist shifting in the sense of becoming something else. I rather see it as expanding. The global visibility of my work is not a departure from the intimate, but an invitation to rethink the relationship between the personal and the public, between the body and the world, between the self and the collective.

I do not seek to commodify my work, but to expand its reach. I do not seek to be defined by a single narrative, but to be part of a broader conversation—one that is not about identity as a fixed thing, but about experience as an ongoing process. I do not seek to be a “representative” of a group, but to be a presence that is both personal and universal.

In this way, my role as an artist is not to retreat from the world, but to engage with it. To be part of the global art market is not to be consumed by it, but to be transformed by it. It is to be a space where the personal and the global, can meet in a way that is not about spectacle, but about truth.

So, yes, I do see my role as an artist shifting. Not in the sense of becoming something else, but in the sense of becoming more open, more engaged. My work is not just about the self, but about the world that the self is part of. And in that, I find both responsibility and possibility.

Souad Haddad, Diva, Acrylic

Souad Haddad, Acrylic, Diva Self Portrait

Souad Haddad, Acrylic, Down The Aisle, 80×60cm

Souad Haddad, Acrylic, Life In Colors I, 60x60cm

Souad Haddad, Acrylic, Life Family of 6, 120x90

Souad Haddad, Acrylic, Mini Blue Garden, 30x30 cm

Souad Haddad, Acrylic, Mini Purple Garden, 30x30 cm

Souad Haddad, Acrylic, Mini Red Garden, 30x30 cm

Souad Haddad, Acrylic, Mini Yellow Garden, 30x30 cm

Souad Haddad, Acrylic, Spring in Tuscany

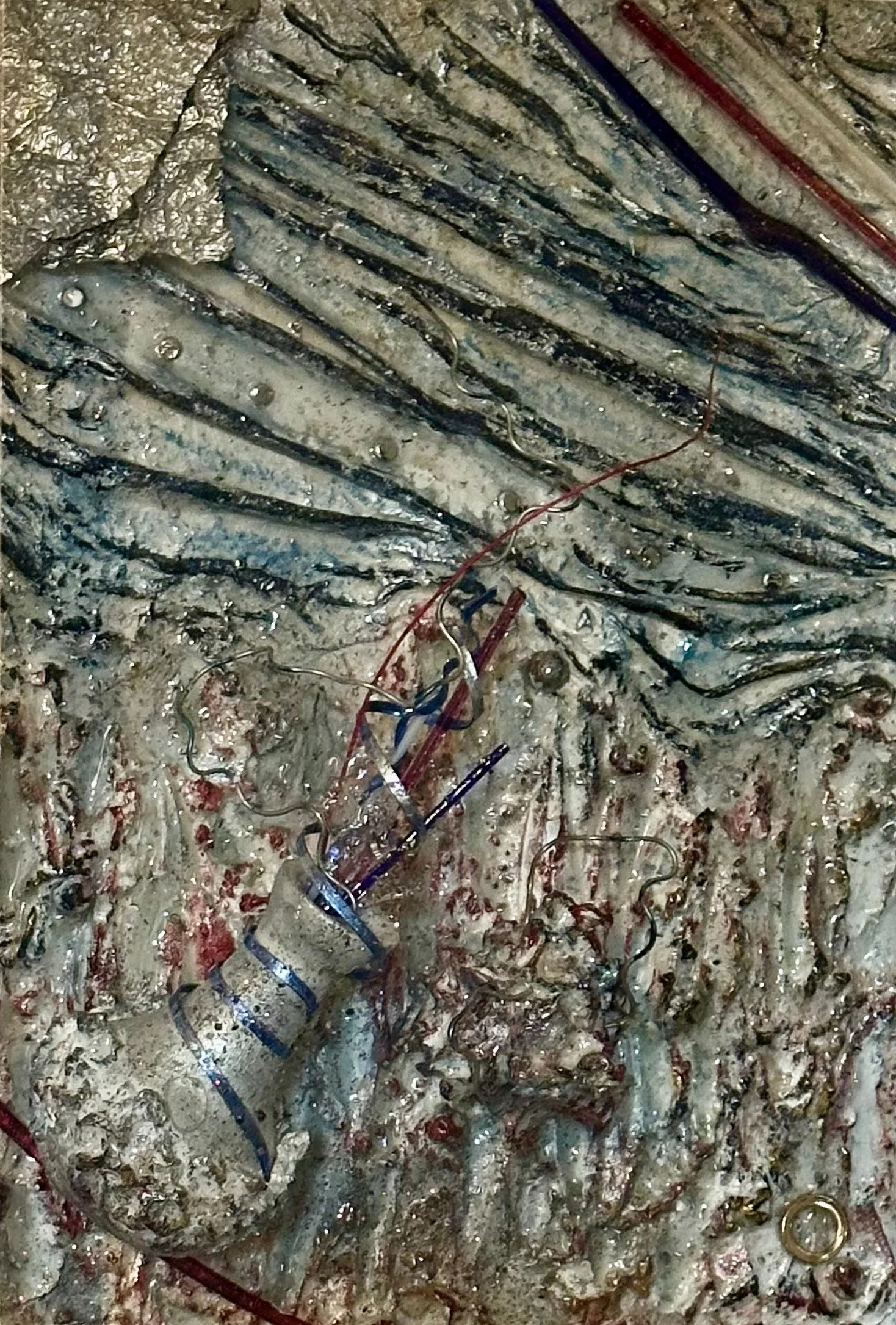

Souad Haddad, Acrylic, The Surface III, 45x45 cm

Souad Haddad, Acrylic, The Surface IV, 45x45 cm

Souad Haddad, Acrylic, Wishes to Love, 100x80 cm

Souad Haddad, Seasons Spring, Acrylic

Souad Haddad, Seasons Summer, Acrylic