Interview with Miyoko Kamimoto

Miyoko, your work posits the flower, the crane, and other motifs not as decorative signs but as entities inhabiting a distinct ontology. When you speak of each form as a living existence with emotion, what conceptual system are you invoking? How do you understand this insistence on presence as an ongoing structure within your thematic universe?

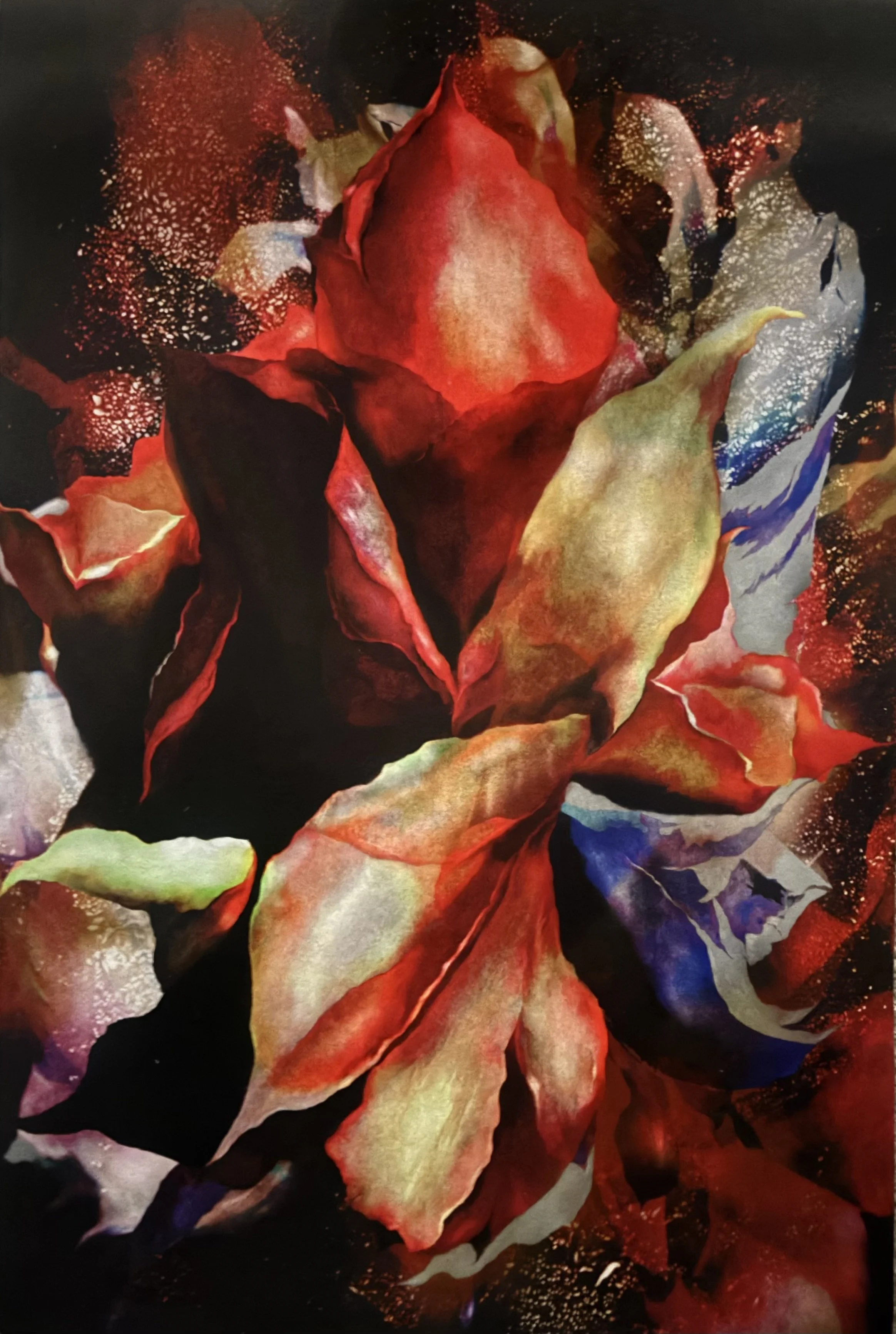

I conceive of roses and cranes as living entities endowed with mind and emotion. This perception arises from an inner, multidimensional worldview that is liberated from physical and temporal constraints, within which such beings reveal themselves in this form. What appears there is not the object itself, but the manifestation of mind and emotion; at times, the universal ideals of truth, goodness, and beauty—which each being may inherently possess—are reflected with clarity and dignity within the rose.

My creative practice is driven by an enduring desire to give permanent form to these inner visions of “existence.” This commitment to preserving what is perceived within the mind as works of art has remained unchanged since my childhood and continues to define the foundation of my artistic pursuit.

The background fields in your compositions operate as suspended time and space, almost as if they were thresholds where representation dissolves into a kind of metaphysical atmosphere. How do you conceive this interval between visibility and invisibility, and what compels you to remain within this thematic paradigm rather than pursuing narrative or figurative clarity?

The conceptual background of my work is rooted in the notion of space-time, a realm in which physical and temporal constraints are dissolved.

This framework is essential for expressing “existence”—that which transcends the concept of time—as an object. As a result, my work often gives form to an invisible, sensory space through light and shadow, abstract memory-like imagery, and a sense of movement. These elements, however, are not employed deliberately; rather, they emerge intuitively in the process of creation.

The use of a PC mouse as a drawing instrument displaces the traditional subject of the artist's hand, creating a tension between physical absence and aesthetic precision. In your view, how does this technique function within the modern discourse of indexicality and the trace? Does it shift the meaning or the status of the creative gesture?

The mention of using a PC mouse as a drawing tool is intended solely as a description of my process. When I began working with my current method, a PC mouse happened to be readily available, and I have continued to use it simply because I became accustomed to it. Drawing with one’s fingers has existed throughout history, and I do not adhere to a fixed notion that drawing must be done with a brush or any particular instrument. Nor do I regard this aspect of my practice as a means of establishing status or distinction.

Your practice now integrates special plaster papers and silk-backed drawing sheets, materials that allow for a multilayered articulation of surface and depth. How do these substrates operate within your thematic logic of illusory space-time, and what kind of phenomenological experience do they activate for the viewer?

Plaster paper is used in the initial stage of printmaking because of its excellent color reproducibility, allowing a strong sense of depth to emerge in the work. Through subsequent additions and surface processing, it also enables a richer expression of multilayered structure; as a result, some works are occasionally mistaken at first glance for oil paintings.

For silk-based paper, I currently use a satin weave, which emits a soft and refined luster. While it does not lend itself to pronounced multilayering, the textile itself possesses an inherent depth that creates a synergistic effect in expression. This material is well suited for those who seek elegance and gentleness in painting; however, its color reproducibility is limited, which restricts color selection at the initial stage of the creative process.

Your digital fresco-giclée method depends on constructing an image through a process of accumulation, revision, and intentional slowness. How does the temporality of making, particularly in a medium often associated with speed, contribute to your insistence on emotional existence as a stable thematic axis?

The time required to complete a single work—from conception to finalization—generally ranges from one month to several months. When a shorter timeframe is required, it is possible to reduce production time by adapting previously created backgrounds for the intended purpose. Additionally, depending on the work, I am considering the future possibility of delivering certain pieces as digital images.

While the form of delivery may vary according to the schedule, I do not believe that such adjustments affect the thematic foundation of the work.

Your achievements extend across Japan, Europe, and the United States, situating your work within a transnational circuit of exhibitions and institutional recognition. How do you interpret the function of these achievements in relation to your practice? Do they anchor your work to a global discourse, or do they serve as reflective surfaces that reshape your own understanding of your theme?

In 2025, I am scheduled to exhibit at ARTEXPO New York in the spring and Le Salon d’Automne in the autumn, and I have also been selected for the upcoming edition of Le Salon next year. Participation in and selection for these internationally recognized exhibitions—each of which attracts significant global attention—has, through the strong responses they generate, contributed greatly to increasing the visibility and recognition of my work.

At the same time, each occasion brings with it a sense of creative tension, as if I am standing once again at a zero point on a new stage. Having the opportunity to achieve results and then pause to reexamine my work is, for me, an essential and invaluable part of my artistic practice.

You speak about having always been drawn to the souls of humans, animals, and nature. Within the structuralist tradition, this could be read as a system of symbolic correspondences. How do you negotiate the boundary between symbolic signification and the direct assertion of existence that your work aims for?

Since childhood, I have perceived humans, animals, and elements of nature—such as flowers and trees—as “beings” imbued with a soul, existing as entities endowed with emotion and inner life. Within my own perception, it may be more accurate to say that I have never felt a boundary between systems of symbolic correspondence and existence itself.

Your background in interior coordination, lighting planning, and spatial design suggests an attention to the architectural frame surrounding your works. How does this engagement with interiority intersect with the interiority of the subjects you render, and do you see your art as participating in a broader discourse about the environment as an extension of emotional space?

I consider the relationship between painting and interior design to be inseparable. For example, the way light falls on a painting affects how it is perceived, and the colors and style of the surrounding interior can enhance the work, creating a synergistic effect in which both are highlighted.

At the same time, my approach to painting is not intended as an extension of an emotional space, but rather as an expression of a separated mind or a vision of another dimension. Ideally, this allows the work to interact visually with the interior while maintaining its own presence—resonating and communicating like a sound. The purpose of display is also an important consideration.

For my exhibition works to date, each painting has naturally emerged from a careful understanding or visualization of the theme and environment of the exhibition for which it is created.

Your images defy the conventional separation between the decorative and the conceptual. They present a tension in which the highly aestheticized surface coexists with the metaphysical claim of emotional existence. How consciously do you work within this boundary, and how does your technical practice sustain this duality?

I consider the relationship between painting and interior design to be inseparable. For instance, the way light falls on a painting affects its perception, and the colors and style of the surrounding interior can enhance the work, creating a synergistic effect in which both are elevated.

At the same time, my approach to painting is not intended as an extension of an emotional space, but rather as an expression of a separate consciousness or a vision of another dimension. Ideally, this allows the work to engage visually with its surroundings while retaining its own presence—resonating and communicating much like a sound. The purpose of display is also a key consideration.

In my exhibition works to date, each painting has naturally emerged from a thoughtful understanding or visualization of the theme and environment of the exhibition for which it was created.

As your recent recognitions accumulate, from permanent collections to Grand Prix awards and international projections, you enter a new phase of visibility. How do you imagine your thematic commitment evolving under the pressure of such expansion? Do you see your technique, your materials, or even your core inquiries shifting as your work enters increasingly global institutional contexts?

For me, who creates work without consciously adhering to established techniques or being influenced by contemporary trends or concepts, awards and recognitions are important primarily as a means of increasing visibility for my practice. This pursuit is not for my own sake as an artist, but for the work itself. Such accolades serve only as a way for my work to be evaluated, acknowledged, and recognized.

The concept of “global” is, for me, simply a natural extension of perceiving all people as inhabitants of the Earth. While awards and selections do bring pressure—and external expectations can sometimes affect creative motivation—my approach to technique and materials remains unchanged. At the core of my practice lies a universal, independent philosophy that guides my work, and I do not depart from it.