Lone Bech

https://lonebechart.blogspot.com/

Lone Bech: Portraiture as Memory, Presence, and Revelation

The story of Lone Bech is not simply the story of a painter, but the story of how a life lived across cultures, professions, and inner landscapes can find its fullest articulation in portraiture. Born in Denmark in 1943 and now based in Germany, Bech began her serious commitment to art comparatively late in life, after careers in international banking and clairvoyant counseling. But to read her paintings as the work of a “late starter” is to miss the essence of her achievement. For what her portraits reveal is precisely the accumulation of decades: encounters with people from every background, intimate knowledge of the fragility of human conditions, and an attunement to the psychological intensities that lie beneath surface appearances. When she says that a painting takes her a lifetime, she is not being rhetorical. She is telling the truth of an art in which each brushstroke carries the sediment of experience.

In the twentieth century, modernism’s embrace of abstraction often pushed portraiture to the margins. Yet in Bech’s work, portraiture is not conservative but radical. It insists on the centrality of the human subject at a time when identity is increasingly dispersed across digital surfaces and fleeting representations. It brings us face to face not only with likeness but with presence, with the depth of being that painting alone can sustain. In this regard, Bech’s work belongs to a lineage that stretches from the ancient Fayum portrait painters of Roman Egypt, through the raw humanism of Käthe Kollwitz, to the existential tremors of Edvard Munch. Like them, she seizes the face as the site where history, memory, and psychic intensity converge.

Among her works, four stand at the heart of her practice, and it is to them that one must first turn: Marguerite Duras(2022), The Conductor (2019), Oliver Brandt (2025), and Gilbert Brandt (2025). Each of these portraits crystallizes her distinct handling of materials, encaustic in the first two, acrylic in the latter pair, and her ability to translate likeness into revelation.

The Marguerite Duras encaustic is exemplary of Bech’s devotion to a medium few contemporary artists dare to employ. Encaustic, composed of beeswax, resin, and pigments, requires heat, speed, and manipulation, yielding surfaces that are at once matte and luminous, solid and fluid. The Fayum portraits, which survive after two millennia, are the historical precedent, and in Bech’s hands this ancient technique feels urgently contemporary. Her Duras is not a nostalgic evocation but a confrontation: the French writer’s face emerges as if from within waxen strata, pale yet insistent, the eyes remote yet piercing. One senses both the opacity of the medium and the transparency of the mind it reveals. It is not just a likeness of Duras but an encounter with her aura, literary, intellectual, fiercely solitary. The encaustic material itself seems to carry the weight of memory, the thickness of history, the enduring presence of a writer who reshaped narrative form.

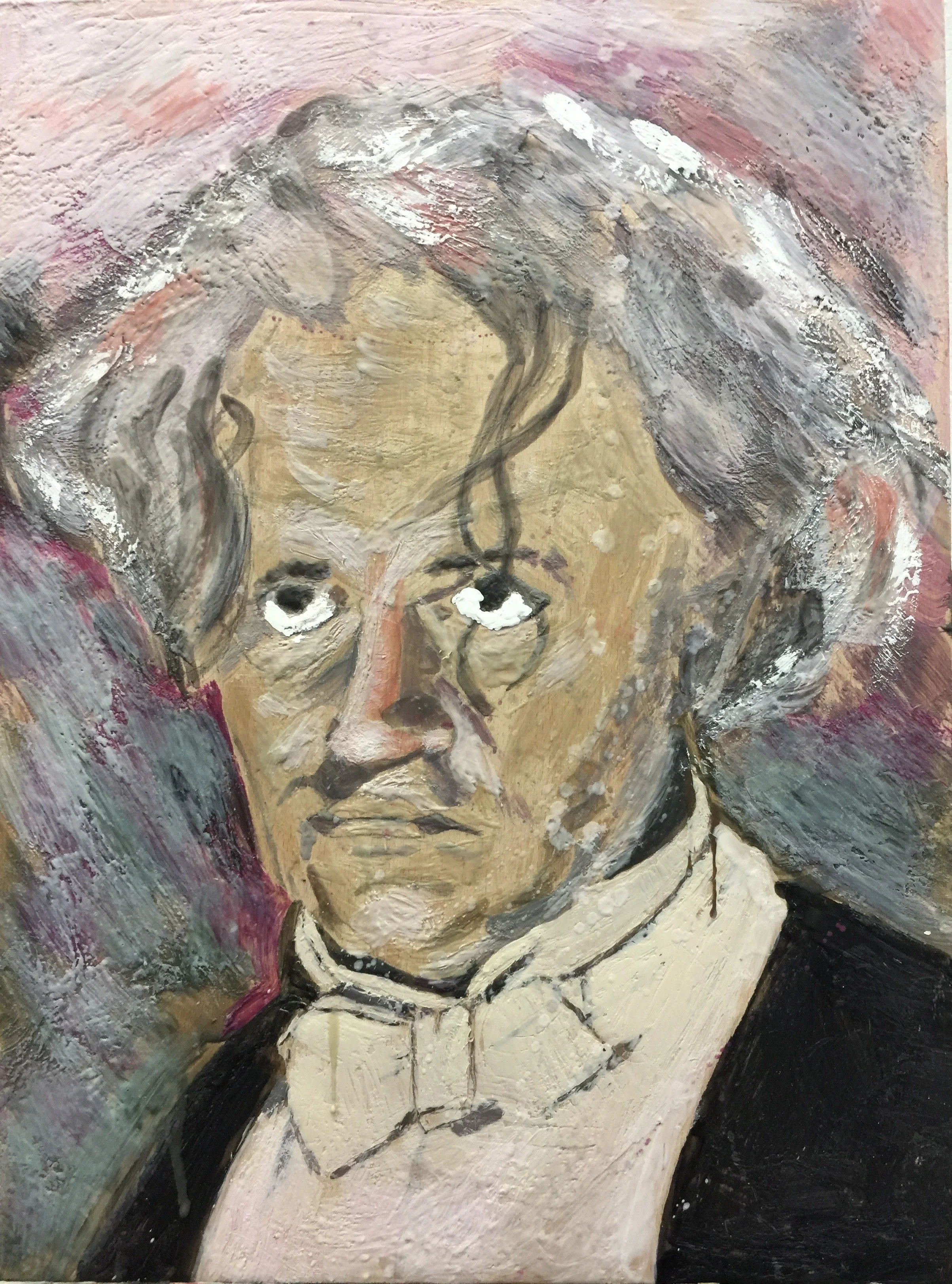

If Marguerite Duras conveys contemplative distance, The Conductor (Niels Arestrup in character) conveys kinetic force. Here, the encaustic surface is agitated, brushed and melted into restless movement. The figure seems carved from molten substance, his gestures arrested in mid action, his authority both commanding and precarious. The wax surface, with its capacity to preserve and yet remain volatile, perfectly mirrors the paradox of the conductor’s art: the control of time itself, the orchestration of sound into order. This portrait insists on the performative dimension of identity, capturing not only a man but a role, not only a face but a force of command.

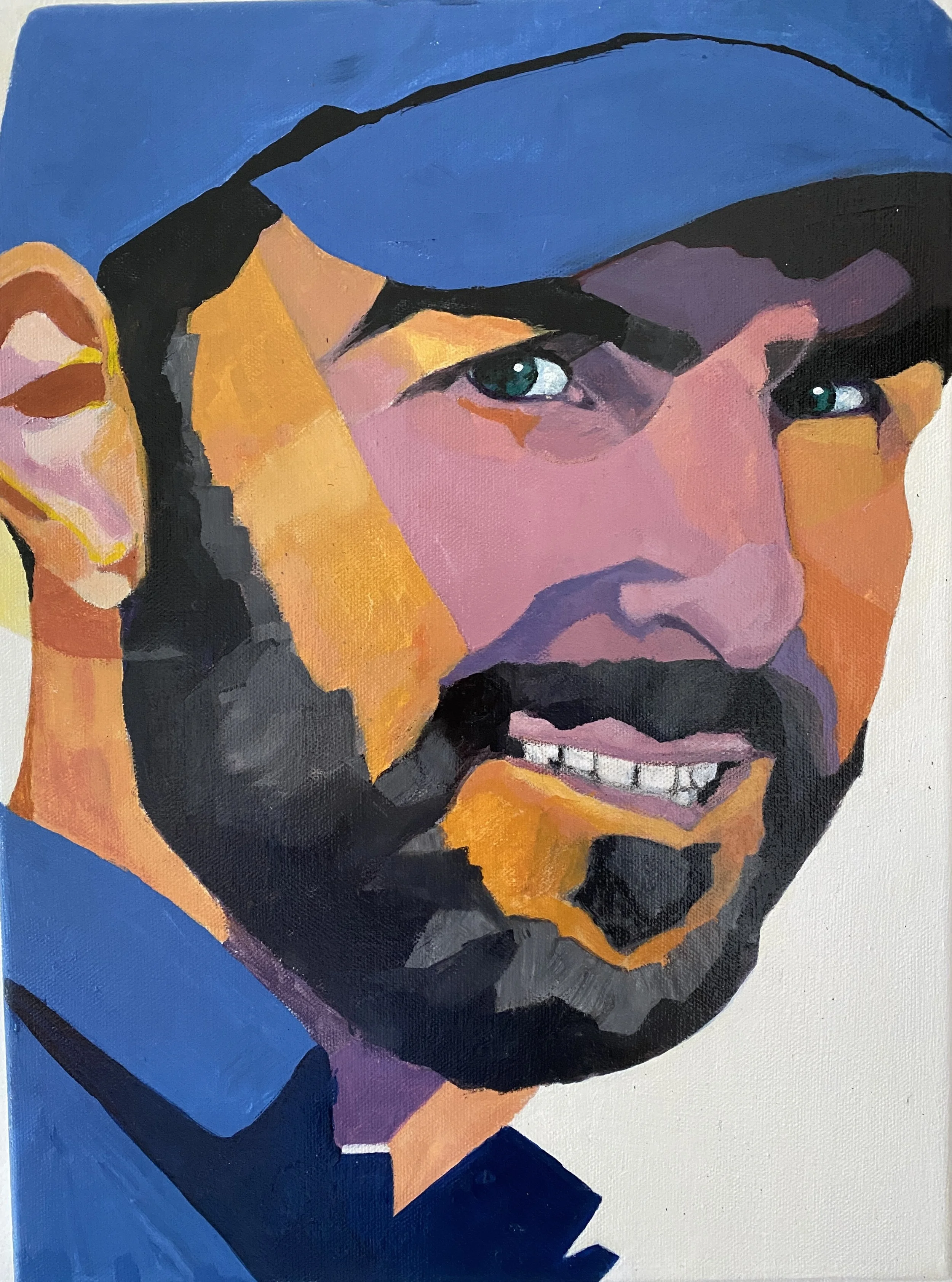

In contrast, the acrylic portraits of Oliver Brandt and Gilbert Brandt exemplify Bech’s control of color and line within the faster, more graphic medium. Both works are alive with sharp contrasts, angular planes, and saturated hues that evoke the language of modern design and abstraction while remaining firmly within portraiture. Oliver Brandt is striking for its play of violet, blue, and flesh tones, creating a face both fractured and unified, expressive of youth and vitality. Gilbert Brandt is bolder, the features more forcefully articulated, the gaze sharper, the character etched in tonal collisions. Together, these two portraits demonstrate Bech’s refusal to be confined to one idiom: encaustic for depth and atmosphere, acrylic for immediacy and intensity.

What I find most interesting about these four works is how differently they embody psychological presence. In Marguerite Duras, the interest lies in the layering of wax itself, the way the material seems to embody silence, opacity, and thought. In The Conductor, it is the turbulence of the encaustic surface that fascinates, the portrait becoming almost performative, alive with movement. Oliver Brandt captivates through its chromatic play, the fractured yet unified face a metaphor for the tensions of youth. And Gilbert Brandt impresses through its forceful clarity, a portrait that is almost sculptural in its definition. These differences show Bech’s rare capacity to let medium, color, and line serve the psychological truth of each sitter rather than forcing them into a single formula.

Beyond these central works, Bech’s broader body of paintings reveals her range. In Georgia O’Keeffe (2025), painted in oil mixed with wax, she pays homage to another pioneering woman artist. The face is carved from light and shadow, its clarity enhanced by the material’s depth. The choice of O’Keeffe is telling: a woman who claimed her independence in a male dominated field, whose abstractions were rooted in close observation of natural forms. Bech’s O’Keeffe is not idealized but strong, her features cut with dignity, suggesting solidarity across generations of women artists.

Karen Tania Blixen alias Isak Dinesen (2016) captures the Danish writer with a mixture of acrylic and pencil. The scale, 170 by 120 centimeters, grants the work a monumental quality. Blixen’s face emerges against a luminous field, severe yet vulnerable, iconic yet intimate. Here Bech demonstrates her ability to monumentalize her subjects without lapsing into rigidity, to preserve their humanity while elevating them to the level of cultural icons.

The Four Romanow Sisters (2023), created in oil mixed with cold wax on cardboard, represents a different mode of portraiture. Rather than focusing on a single face, Bech layers four presences across the surface, their outlines punctuated by patches of red, green, and blue against yellow ground. This work is less about likeness than about memory, about the collective presence of historical figures who lived and perished together. The choice of the Romanov sisters, whose tragic fate is well known, underscores Bech’s preoccupation with human fragility and endurance.

In Martha Argerich (2024), the pianist is painted in oil mixed with cold wax, her presence both intense and ephemeral. The surface captures the paradox of performance: the music cannot be seen, only its effect, yet Bech renders the performer’s concentration, her aura of genius. The wax medium again seems apt, holding the intangible within tactile surface.

Sir Alfred Hitchcock, Errol Flynn, Edvard Munch, Grace Jones (2017) is a tour de force of composition. This large acrylic canvas juxtaposes figures across time and genre: the director, the actor, the painter, the musician. Each presence is distinct, yet they coexist within Bech’s visual field, suggesting the interconnectedness of cultural memory. Hitchcock’s severity, Flynn’s charisma, Munch’s haunted stare, and Grace Jones’s iconoclasm together form a pantheon of modernity. The painting is both playful and serious, an experiment in assembling a chorus of identities across history.

Sitting Katharine Hepburn (2025) presents the actress in repose, painted in acrylic on cardboard. The palette is luminous, the yellow ground evoking both serenity and brilliance. Hepburn’s posture, absorbed in reading, emphasizes intellect as much as celebrity. In this work, Bech once again resists the reduction of her subjects to superficial likeness; she insists on portraying them as thinking, feeling beings, carriers of inner life.

What I find most compelling across all these works is the way Bech uses material to mirror psychology. In encaustic, the thickness of wax conveys depth of memory. In acrylic, the planar surfaces convey immediacy and vitality. In oil mixed with wax, the surfaces oscillate between solidity and translucence, embodying paradox. Each choice of medium is not incidental but essential, shaping how we encounter the sitter. And what is most striking is how she adapts material and method to the individuality of her subjects. There is no formula. Each portrait is an exploration, a negotiation between likeness, presence, and the mystery that lies beyond both.

Her art is important for society precisely because it restores dignity and presence to the human subject. At a time when digital images proliferate without depth, when likeness is endlessly replicated but rarely contemplated, Bech’s portraits slow us down. They demand that we look, that we acknowledge the humanity of the sitter, that we enter into a relation of presence. In this, she aligns with Käthe Kollwitz, whose works bore witness to the suffering and resilience of ordinary people, and with Edvard Munch, whose portraits revealed the psychic tremors beneath the surface. Like the Fayum painters, she insists on durability, on the persistence of presence across time.

Her trajectory, from banker to clairvoyant to painter, is itself emblematic. It testifies to the permeability between life and art, between the professional, the spiritual, and the aesthetic. Her clairvoyance sharpened her perception of human character, her cosmopolitan career exposed her to multiplicity, her late embrace of painting condensed these experiences into a practice at once personal and universal.

In the contemporary art scene, Lone Bech occupies a singular place. She is not an abstract painter, nor a conceptualist, nor a digital experimenter. She is a portraitist, unapologetically committed to faces, to figures, to the human condition. Yet within this apparently traditional field, she is experimental in materials, in scale, in subject matter. She works with encaustic, a medium of antiquity, yet deploys it for contemporary subjects. She paints cultural icons, writers, actors, musicians, yet invests them with psychological presence rather than celebrity sheen. She embraces both small, intimate panels and large, monumental canvases, demonstrating range and ambition.

It is not hyperbole to suggest that Lone Bech has renewed the tradition of portraiture for our time. Her works are not nostalgic but contemporary, not imitative but innovative. They remind us that portraiture, far from exhausted, remains a vital site for exploring memory, identity, and presence. Like the Fayum painters, she preserves faces for posterity. Like Kollwitz, she insists on the dignity of the human subject. Like Munch, she reveals the depths of psychic experience.

In Bech’s portraits, we see more than individuals. We see humanity itself, fractured and whole, fragile and enduring, luminous and shadowed. We see the persistence of the human face as the mirror of history and the vessel of meaning. And in seeing, we are reminded that art’s highest purpose is not only to represent but to reveal.

By Marta Puig

Editor Contemporary Art Curator Magazine

Marguerite Duras, French Writer, 2022, Encaustic on board, 40 x 30 x 3 cm

Niels Arestrup in the role as Conductor, 2019, Encaustic on board, 40 x 30 x 3 cm

Oliver Brandt, 2025, acrylic on canvas, 40 x 30 cm

Gilbert Brandt, 2025, acrylic on canvas, 40 x 30 cm,

Martha Argerich, concert pianist, 2024, oil mixed with cold wax on board, 40x30x3 cm

Georgia O’Keeffe, 2025, oil mixed with wax on board, 40 x 40 x 3 cm

Sitting Katharine Hepburn, 2025, acrylic on cardboard, 100 x 70 x 4 1/2 cm

Karen Tania Blixen alias Isak Dinesen, 2016, acrylic and pencil on canvas, 170 x 120 cm

Sir Alfred Hitchcock, Errol Flynn, Edvard Munch, Grace Jones, 2017, acrylic on canvas, 150 x 200 cm

The Four Romanow Sisters, 2023, oil mixed with cold wax on cardboard, 34 x 60 x 5 cm