Carol Wates

Carol Wates: The Liberation of Drawing in the Digital Age

To encounter the work of Carol Wates is to encounter the persistence of drawing itself, as a practice that refuses to be eclipsed by the shifting tides of technology. It is perhaps paradoxical that Wates, who trained at Chelsea University of Art and has mastered the disciplines of oil, watercolor, lithography, and etching, should find her true liberation within the confines of an iPad screen. Yet this is the paradox that makes her art both urgent and necessary for our time: in her hands, the act of drawing, once bound to paper, charcoal, ink, and canvas, becomes newly electrified within the digital plane, while losing none of its tactile immediacy, none of its structural rigor. She demonstrates that drawing is not diminished by the technological interface but revitalized, expanded, and transported into new zones of visibility.

The history of modernism has been punctuated by artists who redefined what drawing could mean. One thinks of Toulouse Lautrec, transforming the lithographic poster into an expressive surface of nervous, vital line. One recalls Matisse, distilling the gesture to its most essential contour. In the twentieth century, David Hockney’s embrace of the iPad, his capacity to seize light with unexampled speed, carried this lineage forward into a new epoch. Carol Wates, British by birth and cosmopolitan in practice, stands squarely within this lineage, yet distinct. Her work insists on the paradoxical marriage of speed and contemplation. What Wates achieves through the Brushes App is not simply immediacy for its own sake but immediacy in the service of reflection, of capturing the fleeting, the transitional, the moment where ugliness suddenly turns to beauty, a puddle of oil on asphalt transforming into a prism of color, a derelict structure momentarily transfigured by sunlight.

Her practice of painting en plein air situates her within the tradition of the Impressionists, particularly Camille Pissarro, whom she cites with admiration. But unlike Pissarro, working with oils that required a rhythm of patience and return, Wates is able to register the volatility of atmosphere in real time: the shifting cloud, the sudden intrusion of shadow, the iridescence of frost on a winter flower. This simultaneity of encounter and capture defines her achievement. The iPad, in her case, is not a distancing screen but a lens of heightened perception, a medium whose speed allows her to think with nature as it unfolds before her.

Consider Goodbye Winter (2024). In this work, the branches of the tree extend against a waning sky, the fragility of seasonal transition held in delicate tonal shifts. The precision of the drawing grounds the composition, yet the color vibrates with digital luminosity. One perceives here the artist’s gift for contrasts: the skeletal severity of the tree set against a field of quiet, receding light. This is winter not as stasis but as metamorphosis, as the prelude to renewal.

By contrast, Mist Doesn’t Mean Dull (2024) insists on the atmospheric subtleties of fog. Where a lesser artist might reduce mist to monotone opacity, Wates reveals within it gradations of depth, delicate tonal oscillations that evoke the mystery of space. The foregrounded branches are dark yet supple, the background receding into veils of grey green light. The composition insists that mist is never dull, but alive with nuance. It is a work that recalls Turner’s atmospheric dissolutions yet is wholly contemporary in its crisp articulation.

In The Weir (2023), Wates confronts one of painting’s oldest challenges: water. Here the reflection of sky on rippling current is seized with digital immediacy, the brushstrokes simultaneously loose and controlled. One sees the inheritance of Hockney, certainly, yet the piece diverges in its rhythm: where Hockney might insist on broad planes of color, Wates pursues the specific incident of light fractured on surface, the dance of turbulence against stillness. What emerges is not just landscape but an essay on perception itself, the way the eye oscillates between surface and depth, between reflection and flow.

Her still lifes, too, are infused with drama. Victorian Candle Holder (2022) stages the impossible juxtaposition of object and ground. The metallic holder gleams against a field of reflective foil, the purple candle erect, flame fragile yet unyielding. Here, the traditional still life is reanimated through contrast: solid against fluid, line against shimmer, permanence against ephemerality. One senses in this work the artist’s fascination with reflection and distortion, the tension between clarity and dissolution.

Winter Flower Frost Bite (2024) extends this interest in fragility. The petals, vivid in their red and orange hues, appear to be caught within an environment of crystalline frost. The flower itself is rendered with bold color, but the ground is pale, textured, brittle. The piece speaks to survival, to the tension between life and its surrounding hostility. Within the fragility of nature, Wates finds resilience.

Equally poignant is Alive Flowers and Dead Tree (2025), a composition that juxtaposes the vitality of blooming color against the skeletal absence of a dead trunk. This is not merely an image of contrast but a philosophical meditation: on temporality, on the cycles of life and death, on the simultaneity of beauty and decay. In its stark polarity, the work resonates with Klimt’s Farmhouse with Birch Trees, the meeting of vertical and horizontal, of growth and decline. Yet Wates brings the meditation into our present age, where environmental fragility and ecological loss render the theme painfully urgent.

Her attentiveness to seasonal change reaches a crescendo in Autumn Leaves (2024). A single leaf, burnished in orange and red, lies against a surface that reflects the shimmer of water. The digital medium intensifies the saturation of color, while the drawing secures its form. This is autumn distilled into an emblem: beauty at the edge of dissolution, fragility imbued with radiance.

The domestic still life returns in Roses on a Glass Table (2023), where blossoms of crimson and green occupy a transparent sphere, the reflections doubled on the glass surface. This work epitomizes Wates’s obsession with reflection as both subject and metaphor. The roses are not only themselves but their echo, their duplicate, their shadow. In this, one hears the distant resonance of M. C. Escher, whose visual puzzles played with repetition and transformation. But Wates’s version is never schematic; it is lush, sensuous, and alive with atmosphere.

If Roses on a Glass Table explores reflection, Sunset Fire (2022) explores illumination. A chair, draped with fabric, is silhouetted against a burning sky. The intensity of orange and red fuses furniture and landscape, domestic interior and natural exterior. The chair becomes both subject and witness, a presence confronting the sublime. It is at once intimate and cosmic, recalling Van Gogh’s chairs as emblems of solitude, but rendered here within a digital sublime.

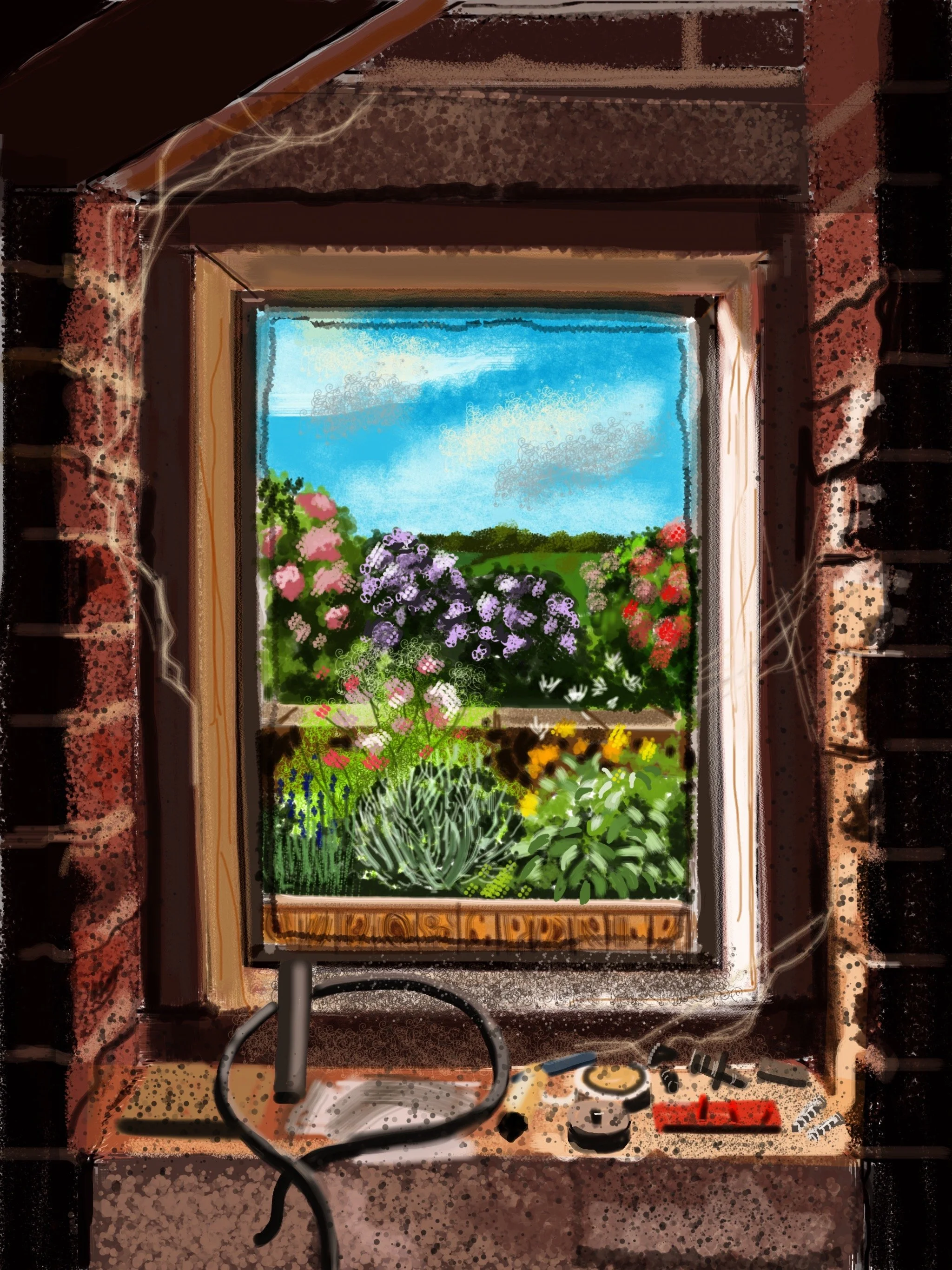

In View from the Boiler House (2025), Wates locates beauty where one would least expect it. The roughness of brick, the detritus of wires and screws, are set against the vibrant profusion of garden beyond the window. The contrast could not be starker: inside, the remnants of labor; outside, the abundance of growth. The composition reaffirms her conviction that ugliness can be transformed by light, that the hidden is always fertile with possibility.

What makes Carol Wates unique is not only her skill in drawing, honed through years of discipline, but her capacity to transfer that skill into the digital realm without forfeiting authenticity. Where many digital works suffer from the sterility of software, Wates’s art is alive with touch, with line, with the nervous energy of the hand. She proves that technology, when approached with intelligence and sensibility, can serve as an extension of the artist’s body, a prosthesis of perception.

Her influences are multiple and acknowledged: Toulouse Lautrec in his graphic line, Klimt in his ornamented passion, Escher in his transformations, Pissarro in his atmospheric light, Warhol and Lichtenstein in their clarity of design. Yet she synthesizes these into a language that is unmistakably her own. Like Lautrec, she knows how to balance space; like Escher, she surprises; like Klimt, she invests ornament with emotion; like Hockney, she embraces the possibilities of the new medium. But the amalgamation is singular, woven into her sensibility as both illustrator and visualizer.

The comparison that seems most fitting, however, is with David Hockney. Both artists, British and steeped in tradition, have turned to the iPad not as a gimmick but as a profound medium of vision. Yet where Hockney’s mark making derives from painterly lineage, Wates’s emerges from drawing and design. If Hockney reasserted the possibility of color and space within digital light, Wates insists on the primacy of line, of structure, of the drawn gesture. In this, she offers not repetition but divergence: another path into the digital sublime.

Why is her art important for society? Because it redefines the way we perceive our everyday environment. The hidden and the contrasts that she seeks, the rainbow in the petrol spill, the shimmer on the broken surface, are precisely the sites where perception must be trained to resist indifference. In a world saturated with images, her art reawakens vision itself, reminding us that beauty is always present, if only we learn to see. Moreover, in an age of environmental fragility, her works speak urgently to the temporality of nature: the frost-bitten flower, the autumn leaf, the dying tree. They are not merely decorative but elegiac, alerting us to cycles of growth and decline that we ignore at our peril.

Carol Wates occupies a distinctive place in the contemporary art scene. She is at once heir to tradition and innovator in the digital present. Exhibiting in Germany, France, and Switzerland, she brings British sensibility to international audiences, offering images that are at once local in their en plein air specificity and universal in their resonance. Her choice to limit prints, to engage NFTs as a form of verification, situates her also within the market debates of digital reproduction and scarcity. She refuses the infinite reproducibility of the digital file, insisting instead on the uniqueness of each image. In doing so, she affirms the value of digital art as serious, collectible, and historically significant.

It is perhaps not an exaggeration to say that Carol Wates’s art is a turning point in the history of drawing. She demonstrates that the discipline can survive the transition from paper to pixel without loss but with gain, gain in speed, in luminosity, in immediacy. Her art is not merely a continuation of drawing but its renewal. In this, she stands as one of the most important visual artists of her generation, ensuring that drawing, that most ancient of practices, continues to live in the present tense.

By Marta Puig

Editor Contemporary Art Curator Magazine

View from the Boiler House 2025 Digital A/3 29.7x42cm

Alive Flowers and Dead Tree 2025 Digital A/3 29.7x42 cm

Autumn Leaves 2024 Digital A/3 29.7x42 cm.

Roses on a Glass Table 2023 Digital 29.7x42 cm.

The Weir 2023 Digital A/3 29.7x42 cm.

Winter Flower Frost Bite. 2024 Digital A/3 29.7x42.cm.

Victorian Candle Holder. 2022 Digital A/3 29.7x42 cm.

Sunset Fire. 2022 Digital A/3 29.7x42 cm.

Mist doesn’t mean Dull. 2024 Digital A/3 29.7x42 cm.

Goodbye Winter. 2024 Digital 29.7x42 cm.