John A. O’Connor was born in Twin Falls, Idaho in 1940.

He studied art with Greg Kondos at Sacramento City College, with Fred Schmid at California State University, Sacramento, with John Golding at Mexico City College, D.F. (now University of the Americas), and with James Weeks at the San Francisco Art Institute. He received an AB with Honors (1961) and an MAA (1963) from the University of California, Davis where he took classes with Joseph Baird, Theophilus Brown, Roland Petersen, Wayne Thiebaud, and William T. Wiley.

He subsequently taught art at the University of California, Santa Barbara (1963-64); Blake College, Valle de Bravo, Mexico (1964-65); Ohio University, Athens (1965-69; and at the University of Florida, Gainesville from 1969 until 2005, when he became Professor of Art, Emeritus. John has had 36 solo exhibitions of his paintings, including a number of retrospectives, and has participated in more than 200 group exhibitions. He has received numerous awards and honors including a National Endowment for the Arts/Southern Arts Federation Fellowship, and several State of Florida Individual Artist Fellowships. His work is included in a many public, university, college, corporate and private collections nationwide.

Could you please introduce yourself and tell us how you started in the arts and your first experience in art making?

I was born in Twin Falls, Idaho, U.S.A., on January 23, 1940. My father, John Francis, was a chef and my mother, Lenore Maude, was an actress in musical theatre.

My early interest was in architecture so I took a typical college preparatory program in high school and then initially studied architectural design at Sacramento City College (California). I quickly realized that this program was unfulfilling and supplemented the design classes with art courses. Taking a painting class with renowned California landscape artist Gregory Kondos, I became obsessed with painting. Working on art in the evenings in the classroom, I found out that both Kondos and Wayne Thiebaud were using it as a temporary studio.

Increasingly confused about what I wanted to do, I quit college in 1959 and moved to San Francisco, California where I took a trivial job that allowed me to paint in the evenings. Frustrated with both the job and the results of my effort to paint, I came to the conclusion that if I could admit that I really didn’t know much about art, I could probably become a very good student of art. So I decided to resume my studies in the summer of 1959 at Sacramento State University-Lake Tahoe Branch. I took classes with Fred Schmid (an artist I knew from Sacramento City College) who advised me to continue my studies in Mexico. In 1959, I moved to Mexico City where I took painting classes with Toby Joysmith and art theory with internationally famous British art critic John Golding at Mexico City College. However, my mother became terminally ill in 1960, so I quit college again and moved back to Sacramento, California to be with her. I set up a studio there and, on a whim, visited the University of California, Davis, where I became reacquainted with Wayne Thiebaud who had recently taken a position there. Thiebaud encouraged me to apply for admission and I did, subsequently receiving an A.B. with Honors (minors in foreign language [Spanish] and mathematics) in 1961 and an M.A.A. in 1963 in painting and drawing. I also studied painting with James Weeks at the San Francisco Art Institute in the summer of 1961.

How would you describe yourself and your artwork?

I am an artist whose work has progressed through several incarnations from Bay Area Figurative (1958-68), Reality and Illusion (1968-86) and the Chalkboard Series (1985-present) (art from all three periods are on website: johnaoconnor.com).

However, I am also an artist who believes that it is very important to re-establish the artistʼs historical contributions to the formation of public policy. I founded, and was the Director of the United States’ first arts policy center, the Center for the Arts and Public Policy (CAPP) at the University of Florida from 1987-2005.

A sample of programs sponsored by CAPP included

• Art and Healing

• Controversial Public Art, the Legal and Ethical Dimensions

• Censorship and Obscenity in the Arts: Public Attitudes/Legal Problems

• Before and After Columbus: The Use and Misuse of the Past

• Women in the Nineties: Sex, Power and Politics

• Culture and Art and the Livability of Communities.

Where do you get your inspiration from?

Many things influence an artist's work. Concepts are forged from impressions, imagination, relationships, education, meditation, dreams, travel, language, other cultures, and various experiences of realities.

Currently, I do a great deal of research on any subject that interests me. And, if I am sufficiently interested, I make up a list of possible images.

What emotions do you hope the viewers experience when looking at your art?

It depends. If they are looking at my earlier work from the Bay Area Figurative period, they are seeing works characterized by vivid color, and a sensual, painterly and, somewhat, expressionistic style. I was also especially interested in the effect of light on interior surfaces. Many images were derived from personal experiences and observation in the mountains of northern California or along the jagged beaches from Monterrey to Mendocino. When I moved to Santa Barbara in January 1963 to begin teaching at the University of California-Santa Barbara, images of bathers, surfers, and the softer, more accessible, southern California beach scenes became a major interest. I also did numerous paintings of my wife Mallory and son Chris and painted some of the rock music stars of the 1960s.

In 1968, I began to explore new ways of working. I had moved to Ohio in 1965 to teach at Ohio University, and my new environment was a shock to me. The landscape was completely different, the light softer, the air much more humid, and the sky was frequently filled with lightening of an intensity that I had never encountered. Although I continued to work in the Bay Area Figurative style after arriving in Ohio, I found it harder and harder to do so. As I responded to my new environment, I began to experiment with new ideas.

In 1969, I moved to Florida to take a teaching position at the University of Florida in Gainesville. Although it was déjà vu all over again, I had less difficulty continuing with my work because, since I was painting from my imagination, it was less environment-dependent than ever before.

I described the paintings from 1968 to 1986 as Conceptual Realism. They are the record of a journey to explore the mystery of illusion and reality. My goal was to provoke thought about how we create our reality. Humor, paradox, deception, and riddle are aspects of this working/process. The result is conceptual realism—not new realism or photo realism. Everything in these paintings is invented. I didn't paint from objects, I painted from my mind. I was interested in things the mind thinks it knows, things seen but not apprehended, things perceived but not truly experienced. By 1986, this particular period in my art practice had completely evolved into the Chalkboard Series.

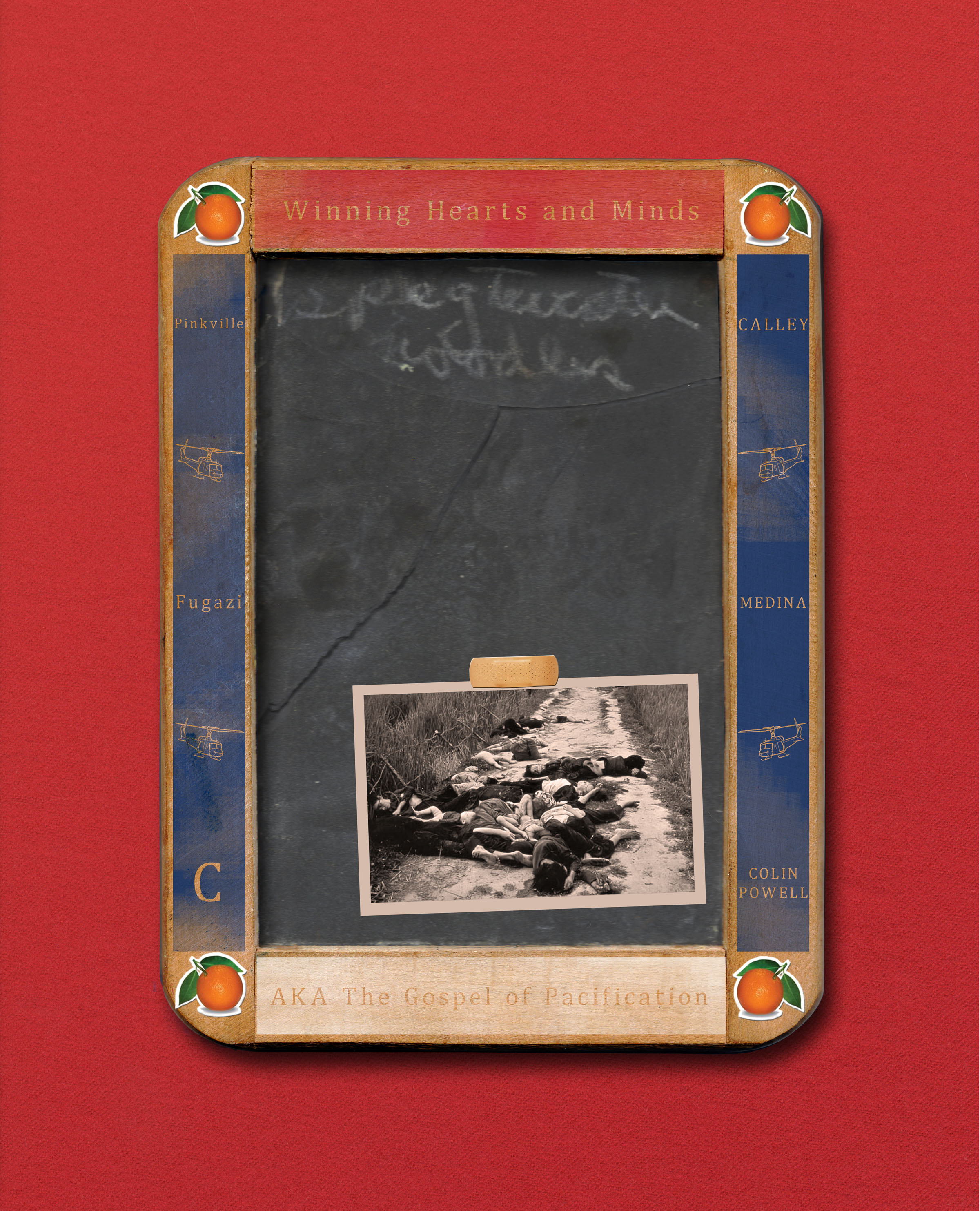

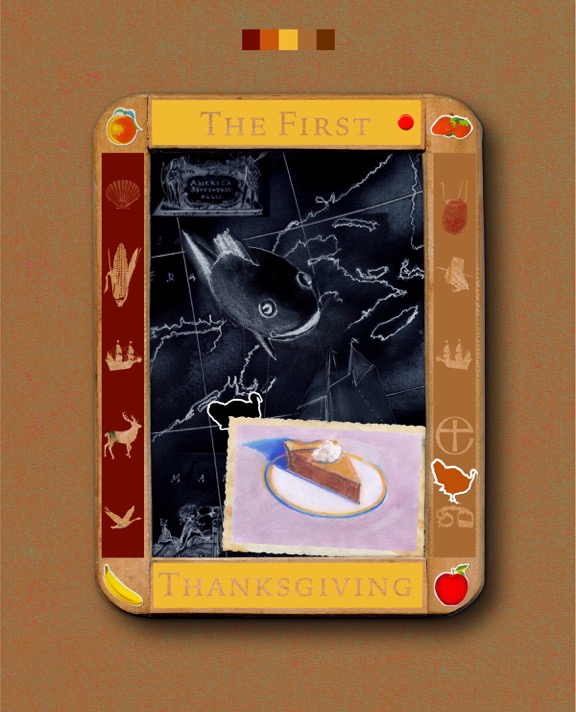

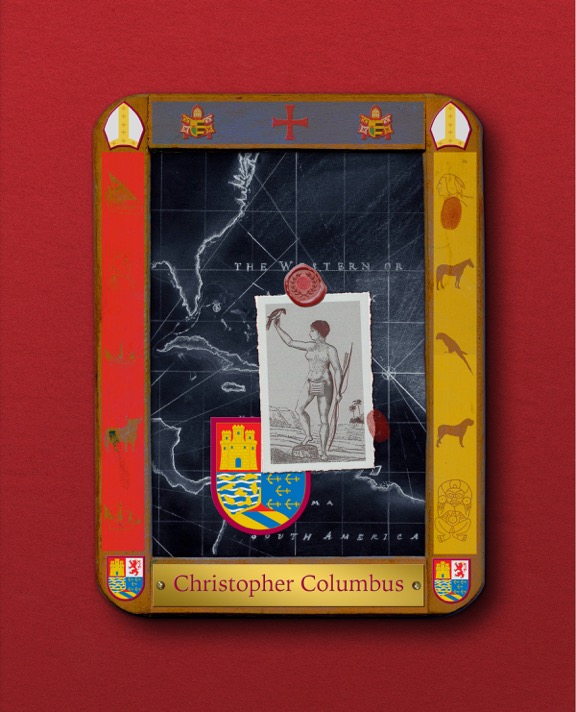

From 1986 on, the Chalkboard Series has been the predominant form of my art. It grew out of work produced in the early 1970s, but the impulse that led to the blackboards was largely undeveloped and not recognized by me. Art has a peculiar way of telling an artist something that he may not understand for many years.

The blackboards images, obviously originated from my classroom experience where I had been surrounded by them for most of my life––first as a student, then as an artist-teacher. As early as 1963, I was interested in the idea of how natural processes could contribute to making a work of art. The blackboards are created using those kinds of processes. Erasing and moving borders become a history lesson: a history of the work itself. Wiping out and/or covering up images and messages goes far beyond the processes themselves. The procedure raises significant questions: What is covered up? Why? What is missing? Within this context, I have become interested again in the concept of the “history painting” in the tradition of such eighteenth century artists as Benjamin West and John Singleton Copley. In paintings such as America and The New Ivory Tower, (on website: johnaoconnor.com) I have focused on the manipulation of words and symbols as “historical documents” used to sway public opinion and to reinforce popular mythology. In addition, the didactic quality of the blackboards allows them to be utilized to fulfill their real function: to inform, to explain, and to teach.

When do you know that an artwork is finished?

Many artists will tell you that they know a work of art is finished when it “speaks to them.” However, I am far more analytical. I ask a lot of questions about the art. Does it answer all of the questions I formulated before I began the work? Unlike earlier in my career when my work was more expressionistic, my current work is far

more idea-oriented. The earlier work led me. I had to respond to a brushstroke here, a drip or dribble there. Now, my current work is primarily a-priori. My earlier work was a posteriori. And, yes, I have read Immanuel Kant.

What has been the most exciting moment in your art career so far?

There have been many exciting moments in my art career since it now spans seven decades. However, two stand out. Being invited in 1987 by noted Art News critic Gerard Haggerty to exhibit in Movietone Muse, Art Influenced by Film in New York City at One Penn Plaza was exciting, but when I arrived at the opening, I was surprised but even more delighted to see my painting, Blackboard Jungle, (on website: johnaoconnor.com) hanging next to a major Andy Warhol painting. And, equally exciting was visiting France in 2001 to view the opening of the exhibition The 33rd International Festival of Painting held at the ancient Château Musée (Mediterranean Museum of Contemporary Art), Cagnes-sur-Mer, France. I was one of sixteen American artists invited to participate in the exhibit and showed four paintings.

How long does it take to produce one work?

That is a question that just about everybody asks, but there really is no answer to it––for me at least. I think that the question itself is a riddle––a conundrum. Some of my artworks take a few days, others take years. Some are never “finished.” The latter are simply works for which I have no further “answer.”

What exciting projects are you working on right now? Can you share some of the future plans for your artworks?

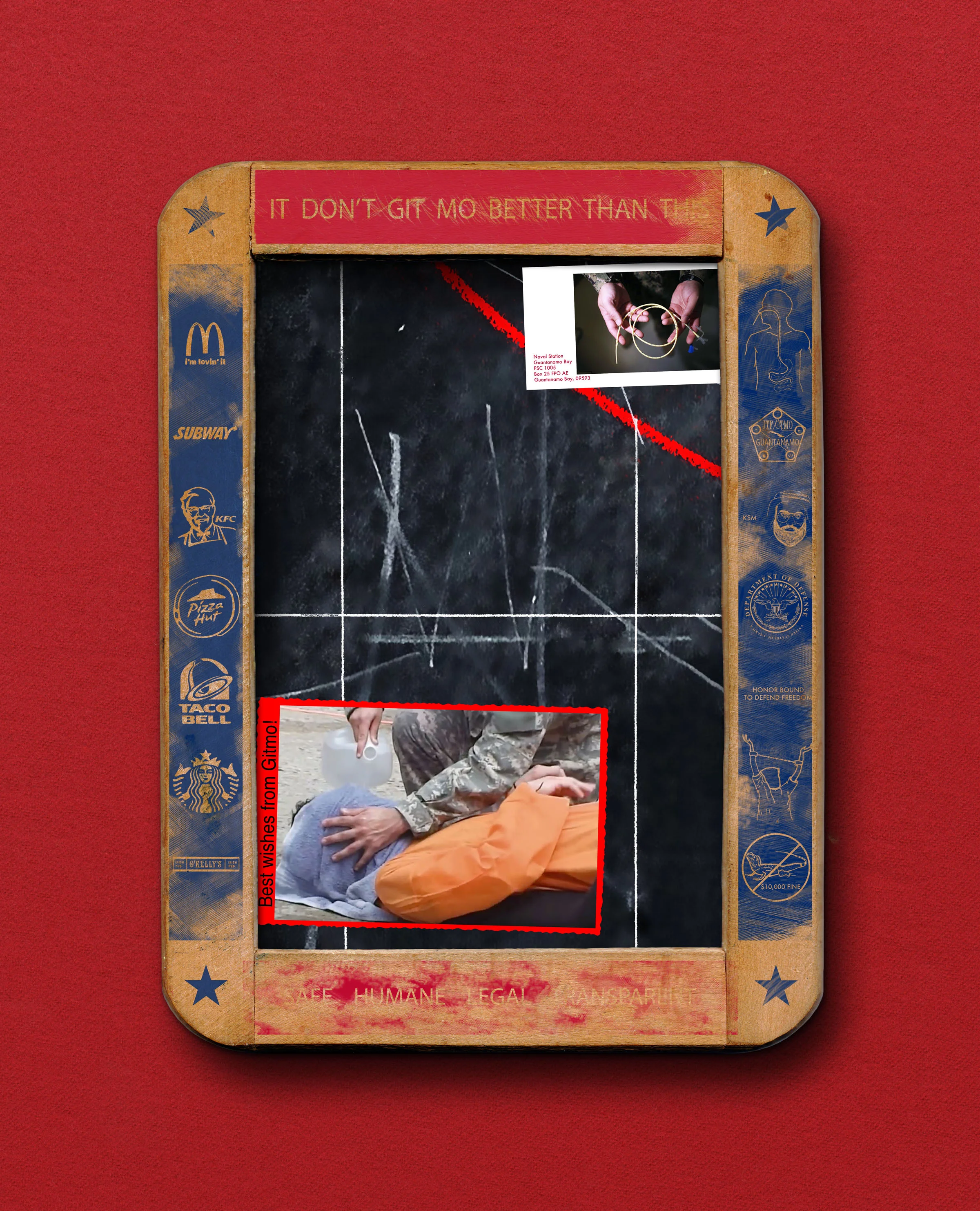

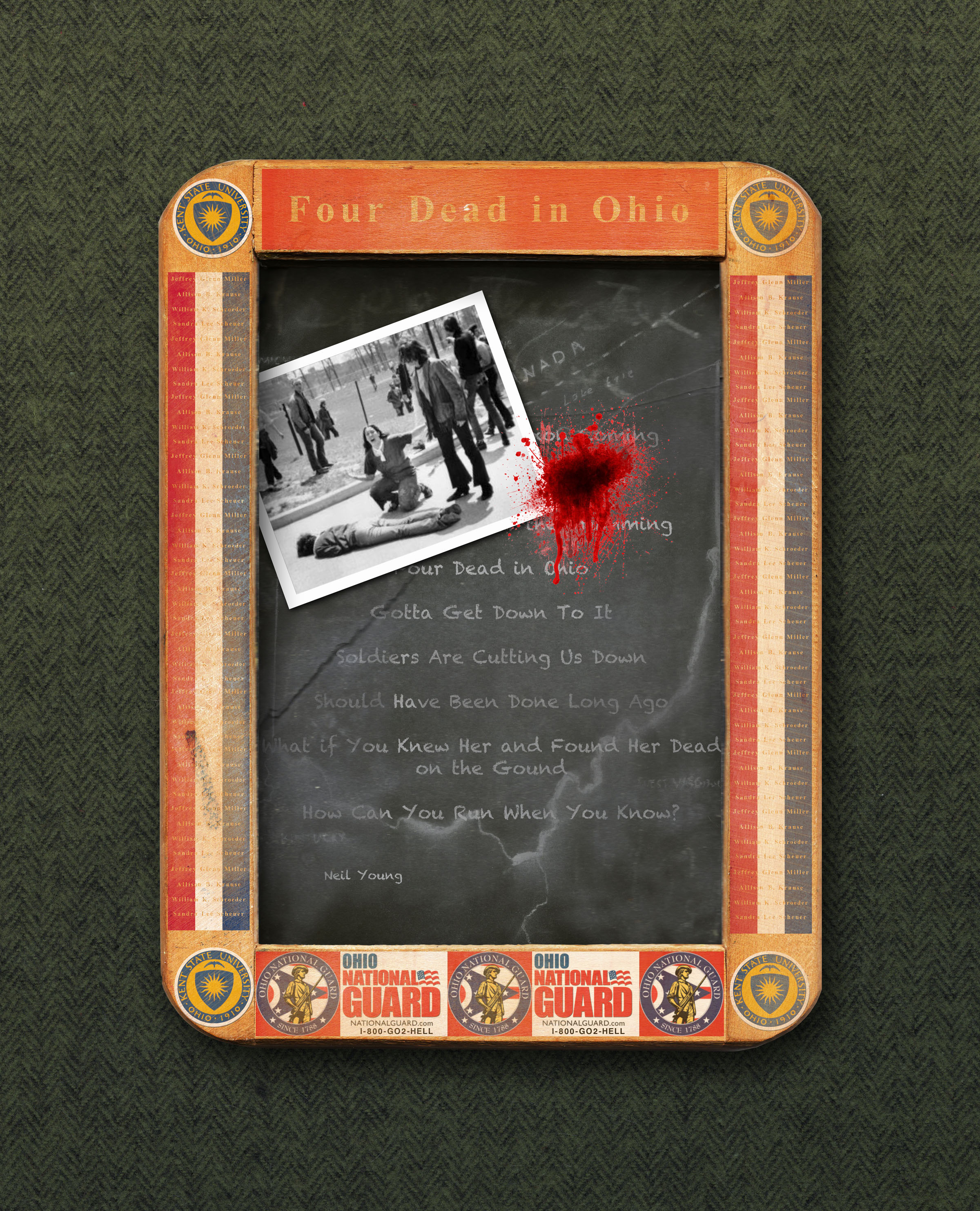

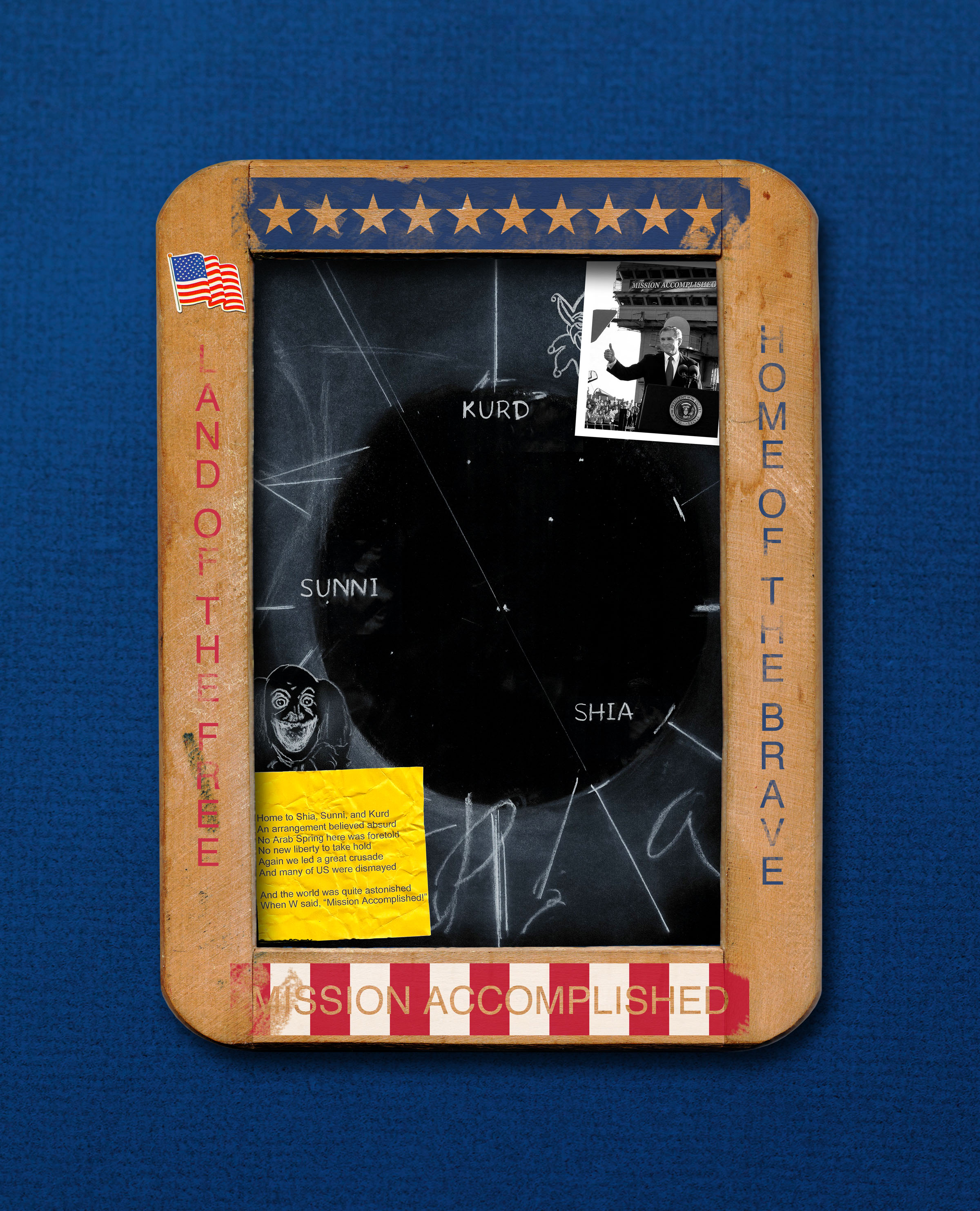

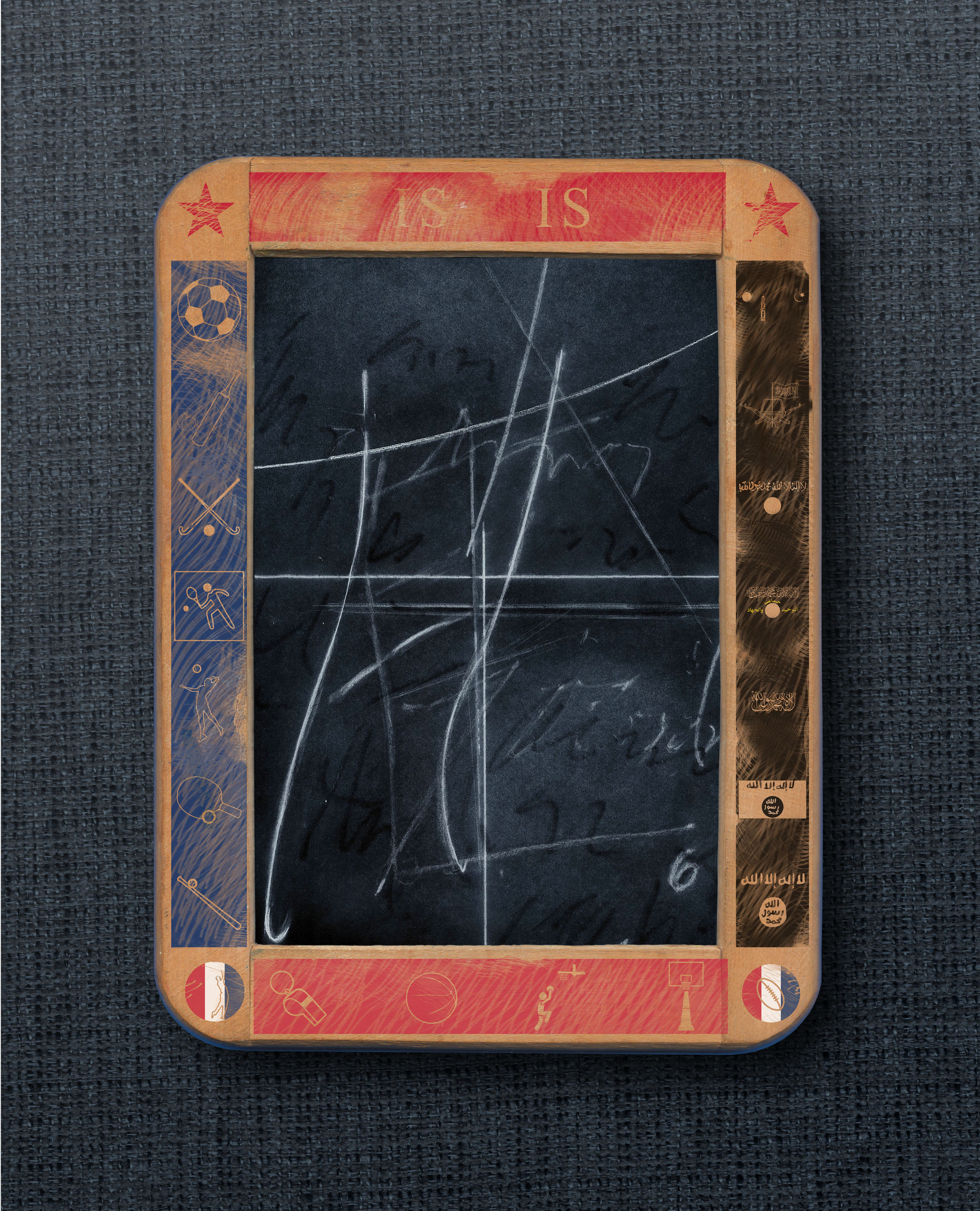

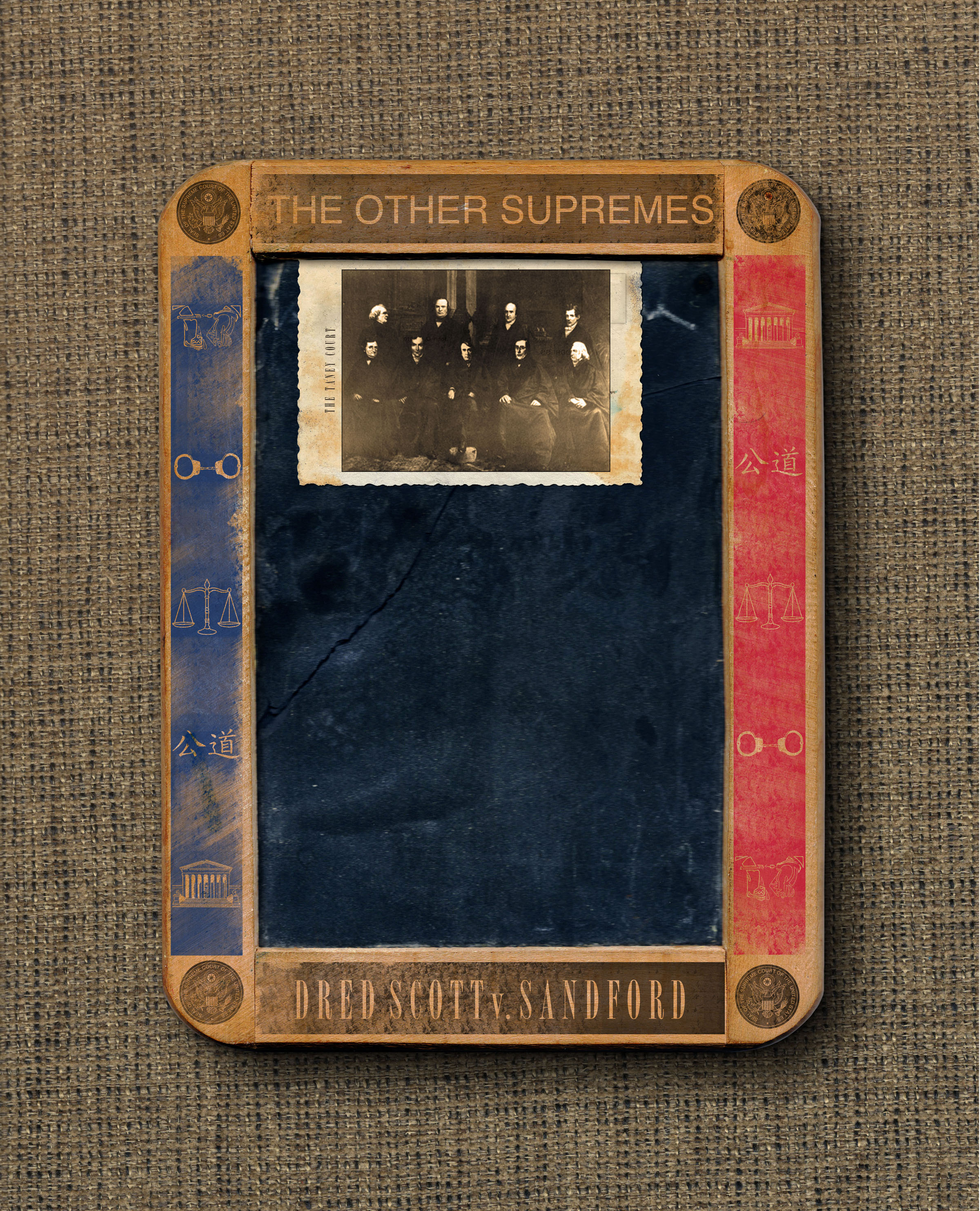

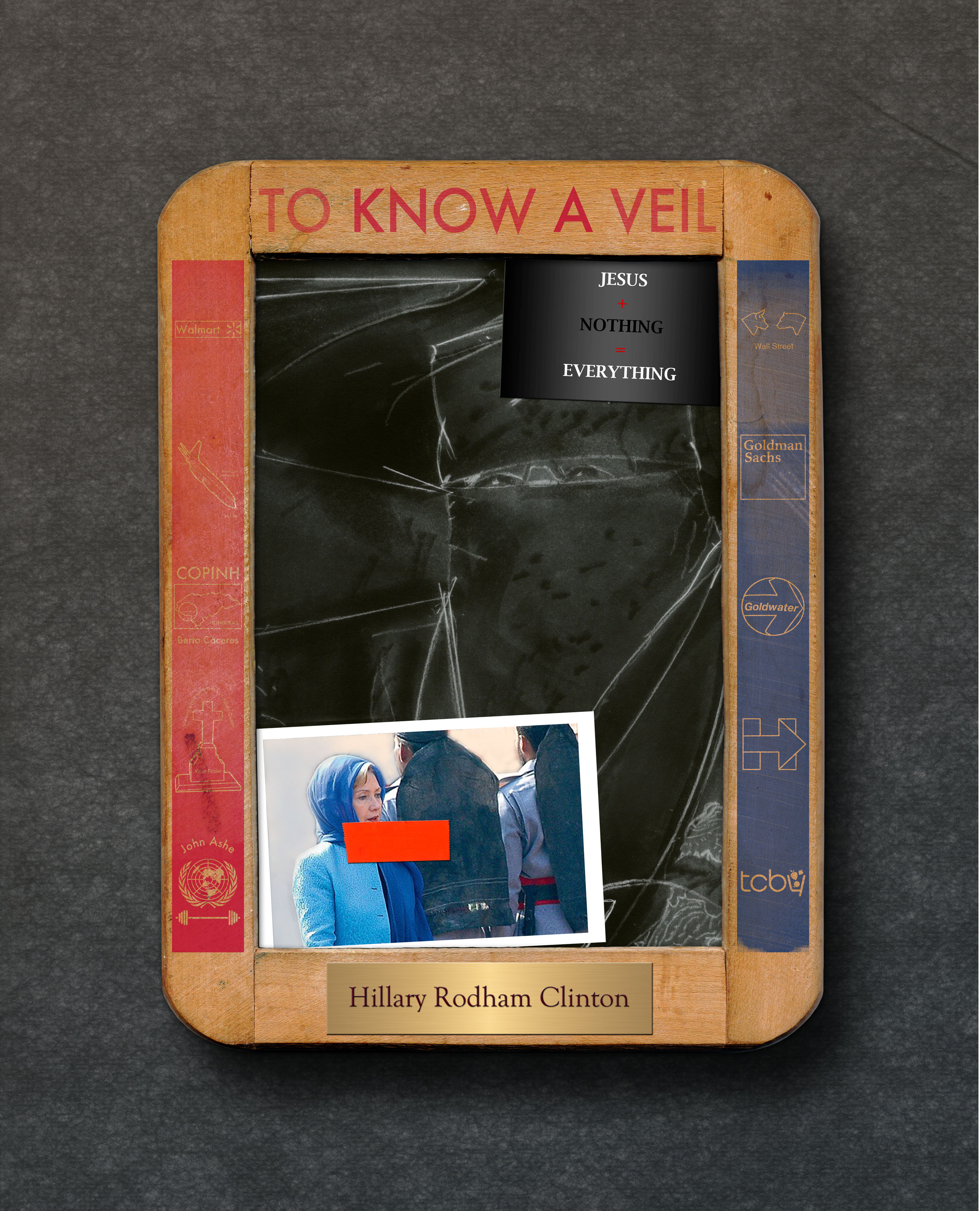

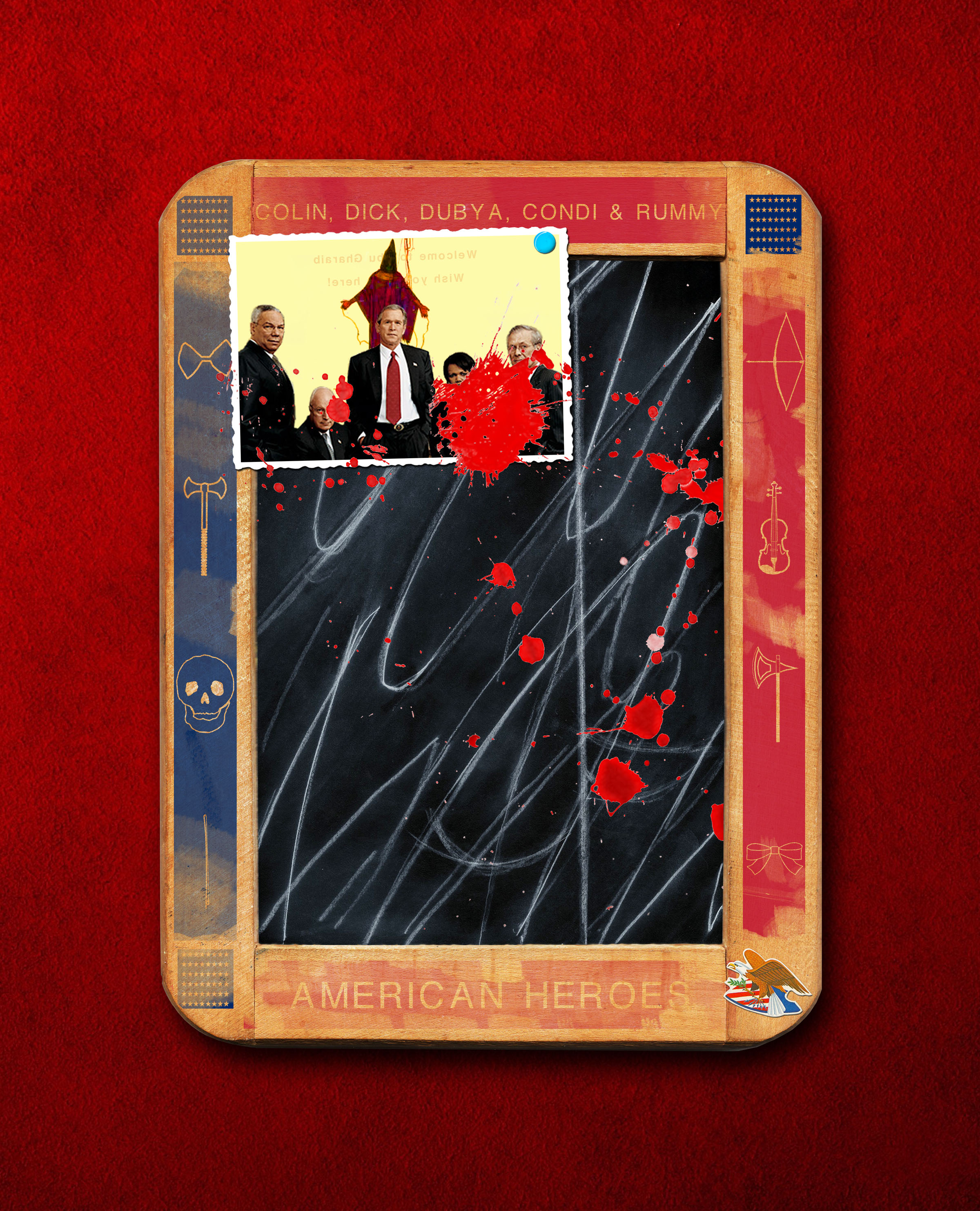

I am currently working on a new series of digital images entitled White Lies Matter: A Visual History of American Deceptionalism. This series takes a very critical look at popular “American History.”

When one seriously examines the history of the United States of America, one will be astonished to find out that what most Americans collectively believe is utterly false. So this series, visually, articulates what actually took place (according to the most reliable sources that I could find).

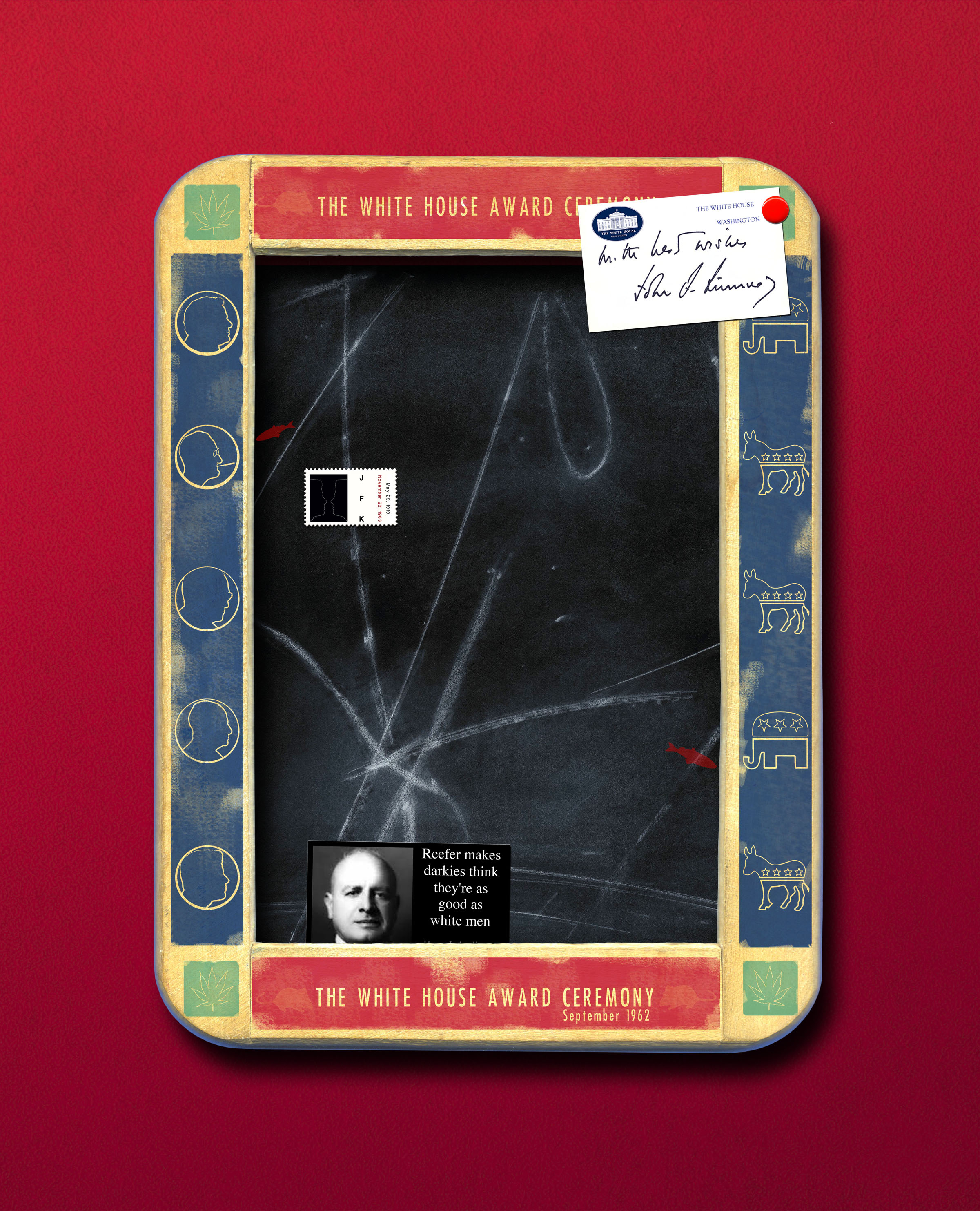

For example, the work Profiles Encouraged, shows how highly admired U.S. President John F. Kennedy deceptively manipulated his followers. While most Americans thought of (and still think of) Kennedy as a relatively liberal Democrat politician, few know, or remember, his awarding one of America’s highest honors to white racist, anti-marijuana drug czar, Harry J. Anslinger. Kennedy’s tribute to Anslinger on September 27, 1962, was “It is my great pleasure to honor you [Harry J. Anslinger] for your outstanding record. You are a most distinguished servant and defender of the American people who are most indebted to you for you have symbolized the best in the service of our country with your unparalleled skill and knowledge, and you deserve our absolute respect, gratitude and admiration.”

That adulation was for the man who, more than anyone in American history, was responsible for the criminalization of marijuana, and the man who said, “Reefer makes darkies think they’re as good as white men.”

This artwork is one of fifty-six that exposes so-called “American Facts”––facts that this artist hopes will be laid to rest by his new digital series, White Lies Matter: A Visual History of American Deceptionalism.

Do you have any upcoming events or exhibitions we should know about?

My new series, White Lies Matter: A Visual History of American Deceptionalism, is projected to be both an e-book and a virtual exhibition potentially available on electronic screens. Any––or all––of the works could be produced as actual, physical art––if there were interest.

This series, is based on my research on the illusory truth effect, lies, and the “illusion of reality” and is envisioned to be the catalyst for a series of related programs that would take place simultaneously during the next several United States election cycles.

Where do you see your art going in five years?

Following the completion of my new series, White Lies Matter: A Visual History of American Deceptionalism, I plan to begin a new series that is an homage to Rock and Roll music and artists. This series will be titled Thank You Rock and Roll and will feature images that convey the ideas of prominent rock musicians who confronted significant social issues. It also will include some work that simply honors this genre. Ironically, this series takes me back to some of the work I created sixty years ago. So, in a way, you could say that my work has come “full circle,” but it really has returned to earlier ideas so that they now can be completed by a far more knowledgeable artist.