Eriko Kaniwa - SENSEGRAPHIA FINE ART PHOTOGRAPHY

Born in Tokyo. Eriko Kaniwa is a Tokyo based fine art photographer. After graduating from university, she worked as a producer at a major Tokyo television station before studying photography independently. In addition to exhibiting photographs in individual and group shows and continuing to work as a photographer, she has explored alternative education, cognitive science, depth psychology, and art communication.

In 2014, she began developing a workshop program that applies the potential of photography to aesthetic education. She presented the program at domestic graduate schools, foreign-owned firms, international conferences, and think-tank-style business schools, and received positive feedback from over ninety percent of participants.

Sensegraphia is the name she has given to a conceptual redefinition of photography, in which experiencing life in a profound way, by stimulating the senses through visual aesthetics.

The photo book “JOKEI: Symbols of Nature Worship, Sacred Places in Japan.” was awarded internationally by IPA, as the one of the best fine art photo book.

ARTIST STATEMENT

-Beyond sight, Aesthetic insight

Just as there are infinite gradations between the light and shadow that make up the essence of photography, are there not also infinite forms that exist between living and non-living (organic and inorganic) The more I photograph nature, the more I wonder, how can we, today, perceive these in-between forms?

Even today, many landscapes exist in Japan that symbolize nature worship. I am affectionately proud of the values that have flourished within this natural context: the wabi-sabi aesthetic of imperfection and impermanence; the pursuit of subtle and profound grace; the awareness that humans are a part of nature and are deeply entwined with its dynamics. I wonder if this philosophical culture, characterized by empathy with nature, evolved not first and foremost from the natural landscape itself, but rather from the contemplation and perspectives of those who viewed it.

To take photographs and look at them is to become a witness to the manifestation of events that appear and disappear within the flow of time immemorial. For me, photography is not a philosophical metaphor for death or the past, but rather a crystallization of the temporal dimension with which human react so vitally, achieved through the medium of light. It is an action in the fourth dimension, and attempt to step outside the flow of time and grab hold of something to confirm that we live in a world side by side with death. Beyond mere seeing lies contemplation and communication of the world.

Beauty and art overcome the obstacles of language and distance, allowing us to experience, express, and share a feeling of respectful awe, as well as the moving realization that human beings exist as just one part of planet Earth.

To me, that is photography. It is my hope that by building on the concepts of nature that have been passed down across generations in my native country of Japan, we will together be able to sense something, and compose a story.

Spiritual Landscape Project

"Floating Sanctuary --Water scape with Torii gate”

Since ancient times, torii shrine gates in Japan have symbolized the boundary marking the threshold of sacred ground. It is believed that the practice of torii construction based on bird worship dates back to the Yayoi period (around the 5th century BCE).

People revered the natural realm that lay beyond the reaches of human power as holy, regarding mountains, seas, waterfalls, islands, and ponds as objects of worship, and erecting torii to protect them. In some instances, they deemed these sacred places “forbidden lands” to protect the land itself or the vegetation growing on it; at the same time, they prayed that the spirits inhabiting the natural world would guard them in their daily lives. Whenever I glimpse one of these torii within the natural landscape, my spirit feels for an instant like it has been purified, and an unstoppable feeling of devoutness washes over me. The next moment, I sense this divine presence evaporating and rising into the sky.

In the case of torii built in water, they are often constructed on top of small islands in a sea or lake or off the tip of a cape, on protruding rocks, or amid other landscape elements that draw the eye. Our ancestors who lived on the Japanese archipelago, surrounded by seas, must have sensed divinity in the slightly extraordinary elements of an otherwise ordinary landscape. They built torii in these places, and in doing so began a prayer that has continued across generations, for safe oceangoing journeys and fishing expeditions, for abundant harvests of the sea’s bounty. Torii are not only the gates we pass through when visiting a shrine; those that stand within the natural landscape function as symbols of awe and piety toward nature’s power that have shaped the spirit of the Japanese people throughout history.

There are times when nature unleashes its power in the form of natural disasters, causing great harm and evoking our fearful awe, but nature also supports our livelihoods and daily lives. The Japanese language provides over a thousand ways to express the concept of “rain,” and as many for “wind”; the fact that these words are scattered as a matter of course throughout Japan’s ancient texts is evidence of the inseparable link that the Japanese people sense between nature and religious belief. Language, faith, and prayer, in other words, are for us intimately connected to natural phenomena, climate, geology, and topography.

The reason I feel both piety and spiritual calm when I see a torii rising from the water is, I believe, because this is an elemental landscape for the Japanese, a symbol of stopping in the midst of our busy lives, and looking and offering up a prayer to nature. It is the real landscape that is the foundation for the imagined landscapes we see in our mind’s eye. I believe this is perhaps the prehistoric source of the Japanese concept of spirituality that we call the Eight Million Gods—the belief, appearing even now in modern films such as those by Studio Ghibli, that divinity can be found even in a mote of dust.

When I visit these special landscapes to capture them with my camera, and find them littered with plastic bottles, bags, or empty cans, or I find the ocean poisoned with chemicals, the devastation of the surrounding environment appalls me. It is evidence that modern people have lost the ability to see the divine within landscapes and act with care, and that we Japanese are in the midst of losing our spiritual grounding. The purpose of religion is not to make us to bring our hands together and utter certain words; it is to shape our moral attitude and ethical perspective on life. It can perhaps even be said that these changes lie at the root of each and every environmental crisis.

On a final note, the characters for “torii” in Japanese can also be read literally as “presence of birds” or “place for birds”. Interestingly enough, while I was shooting, birds would often come to rest their wings on the torii gates, and I have included some photographs of them in these images.

Spiritual Landscape

Wedded Rocks "Meotoiwa" - Origins of the worship of paired rocks.

The most famous pair of wedded rocks in Japan are those at “Futamiura” in Ise Bay, Mie Prefecture. According to the legends of Futami Okitama shrine (founded in the early 8th century), the rocks were worshipped 2,000 years ago as “torii of the sea,” with the purpose of venerating a sacred stone below the surface of the distant ocean glimpsed between them.

The worship of paired rocks can be traced to the days of the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki (The oldest and second-oldest Japanese written works, composed in the early 8th century), and the Tenson Korin. The Tenson Korin, which details the heavenly descent of the sun-goddess Amaterasu’s grandson, Ninigi, is the mythologized tale of the arrival on the Japanese archipelago of the king of the Wajin people from the ancient land of Tsushima.

The practice of worshiping paired rocks may have originated because the king likened a pair of rocks where he landed in Fukuoka, Kyushu, to his native land of Tsushima, and therefore deemed them sacred, making pilgrimages to them.

Later, the capital was transferred to the Kinki region, and the locus of paired rock worship was transferred east as well, most likely to the wedded rocks at Futamiura, Ise. Some therefore believe that the worship of paired rocks in Japan originated at the wedded rocks in Itoshima, Fukuoka Prefecture, in northern Kyushu. I find this theory extremely compelling, especially given the excavation in 1998 of the three sacred Imperial Regalia of Japan from Fukuoka’s Yoshitake-takagi.

The paired rocks at Chikuzen Futamiura in Itoshima are dedicated to Izanagi and Izanami, the married deities of Japan’s creation myth. It is not difficult to imagine that this is how the practice of calling paired rocks “wedded rocks” originated. Whether or not that is the case, it remains true that wedded rocks do not merely symbolize the bonds of love, but are also deeply connected to the origins of Japan.

Birds of Japanese Myths and Folklore

This series was inspired by an experience I had while photographing torii gates built in water, which are a symbol of Japanese nature worship. The word torii is written using the character for “bird,” and fittingly, as I stood there, a large flock of birds landed on the torii to rest. What must our ancestors have thought when they saw birds perched on the gates built to welcome the gods of nature? These photographs express the impressions I felt as I came face to face with the birds depicted in folklore and mythology—cranes, eagles, and chickens. My hope that, rather than viewing the images of these birds as wildlife photography, you will experience them as fine art.

For more details, please go to the page

http://sensegraphia.jp/#/page/birds-of-japanese-folklore/

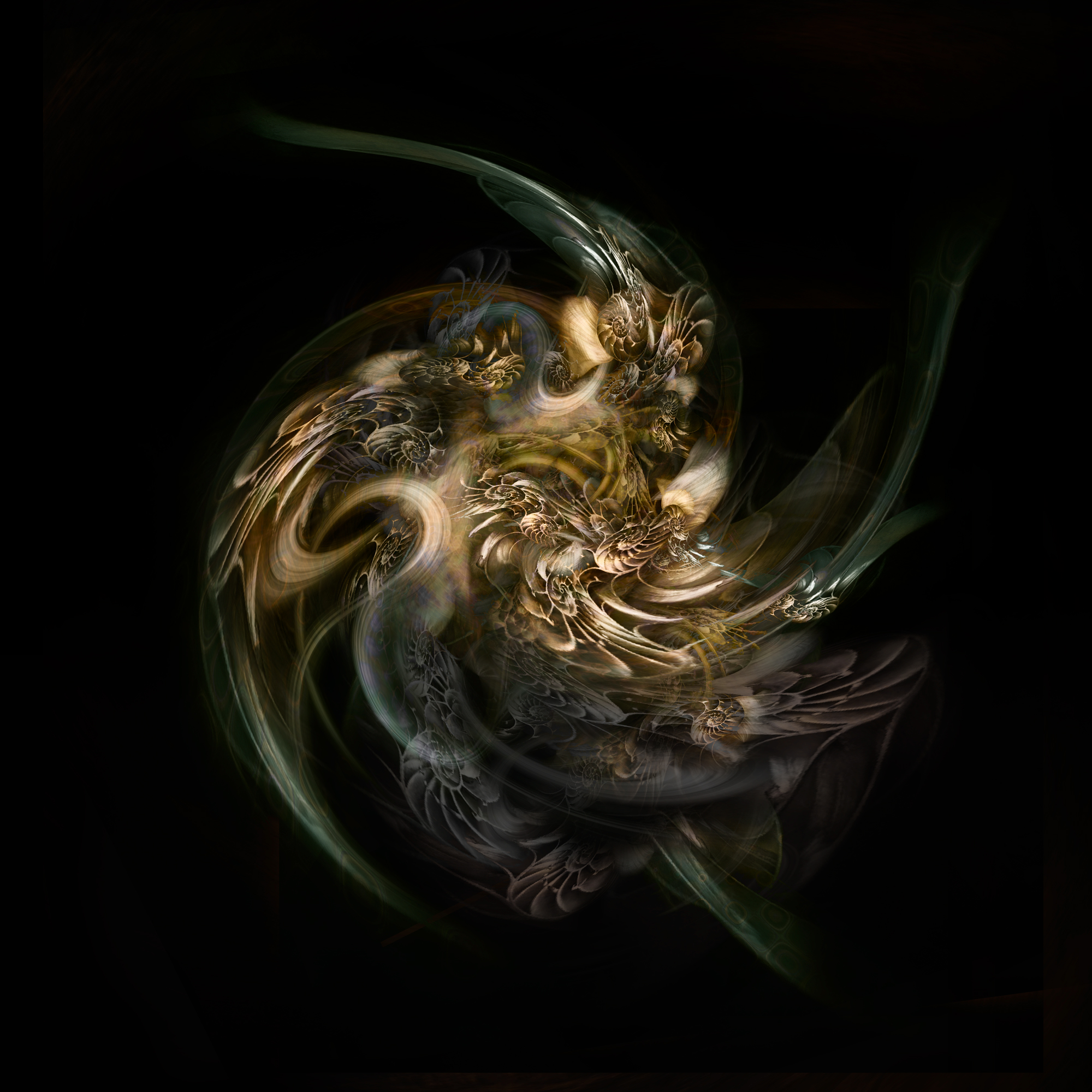

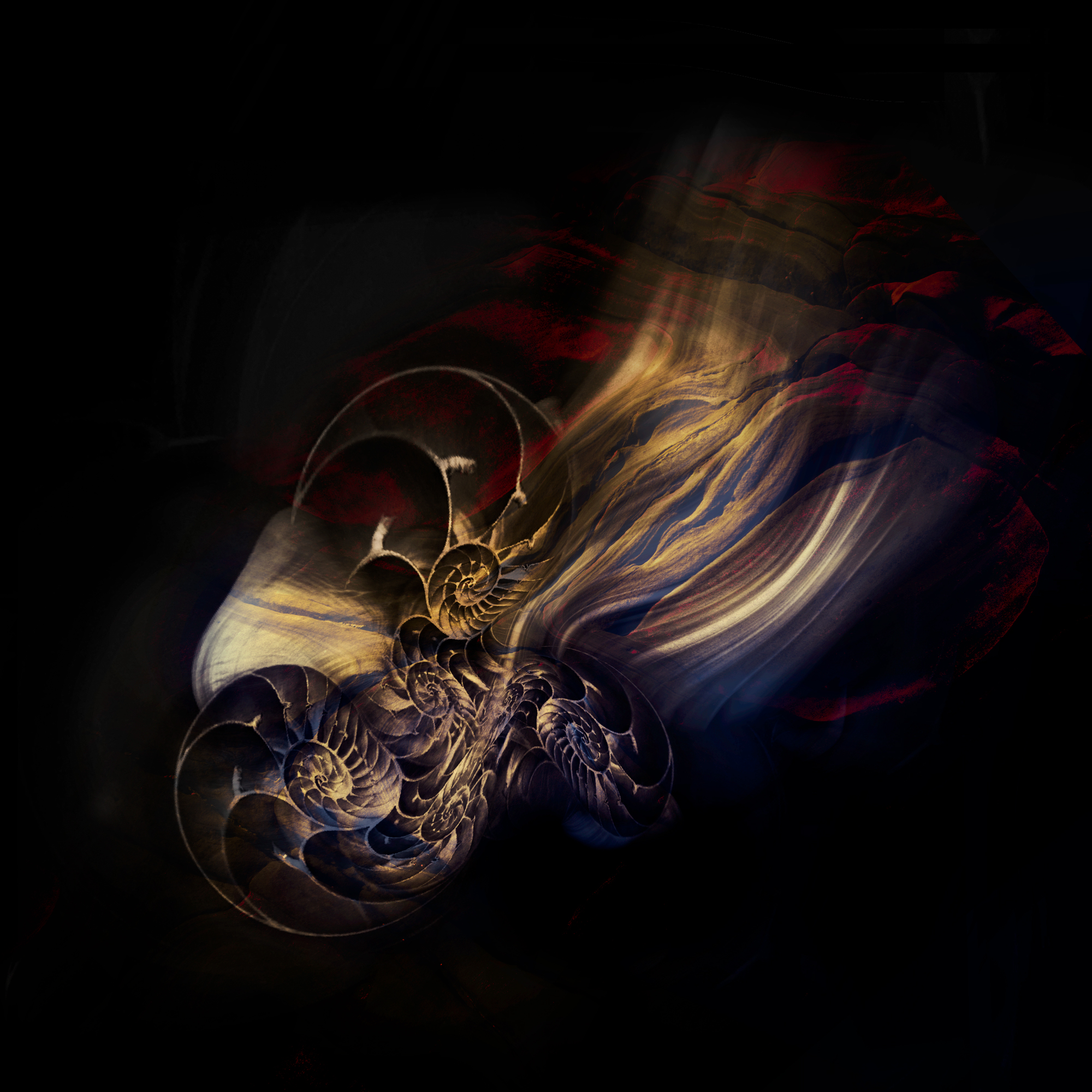

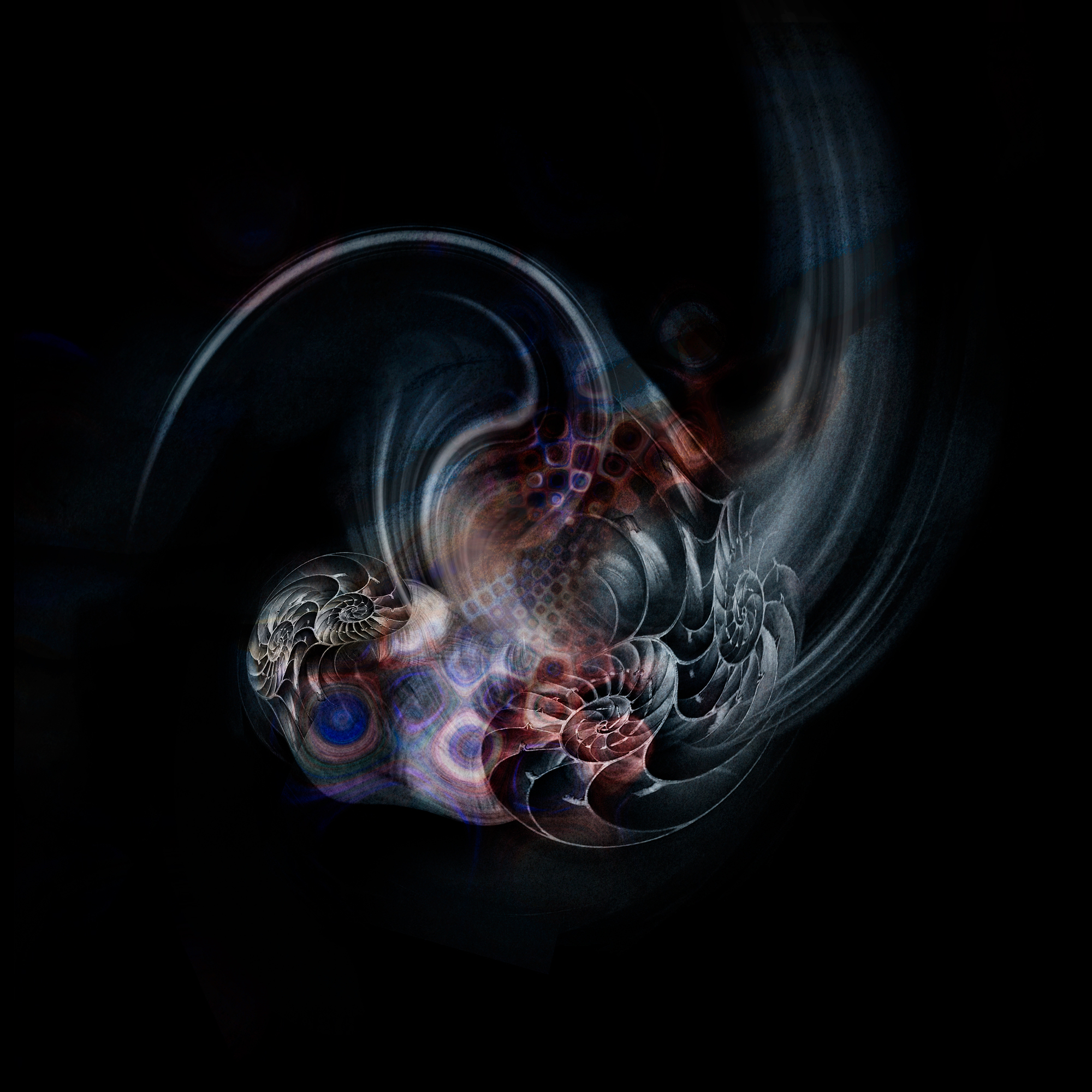

Nautilus Universe

The spiral is, for me, the most intriguing and inspiring motif. In particular, the shape of the nautilus shell expresses the energy of the universe in an architectural form, and always makes me think about the ways in which this energy is at work on Earth. In this experimental work of art, I used digital enhancement to visually present my sense of the flow of energy within this shell. Doing so allowed me to once again glimpse a tiny universe. Photo taken with Leica Q, Macro mode.

The one of this project work has been COMMENDED by SONY WORLD PHOTOGRAPHY AWARDS 2017-2018, it will be exhibited digitally at Somerset house April in London UK.

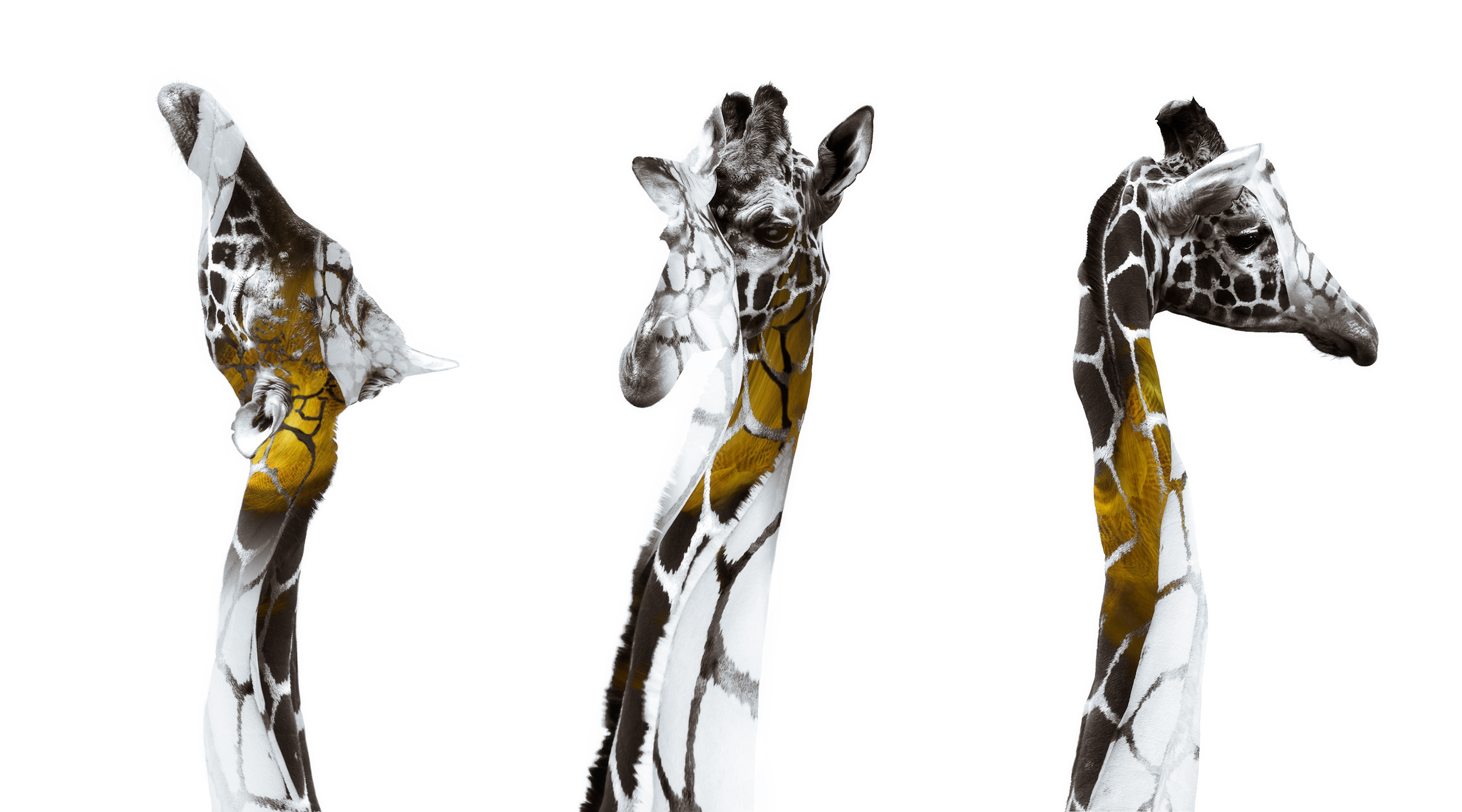

Intended nature

Wild animals in the created nature environment (Digitally enhanced)

Zoo animals in the created environment by human, It makes me look -DESIGNED- in some way, and losing wild instinct and LOST in the vast fake. Some of them are willing to accept it and some of them are really struggling with it. They are asking us what is NATURE?