Interview with Craig Robb

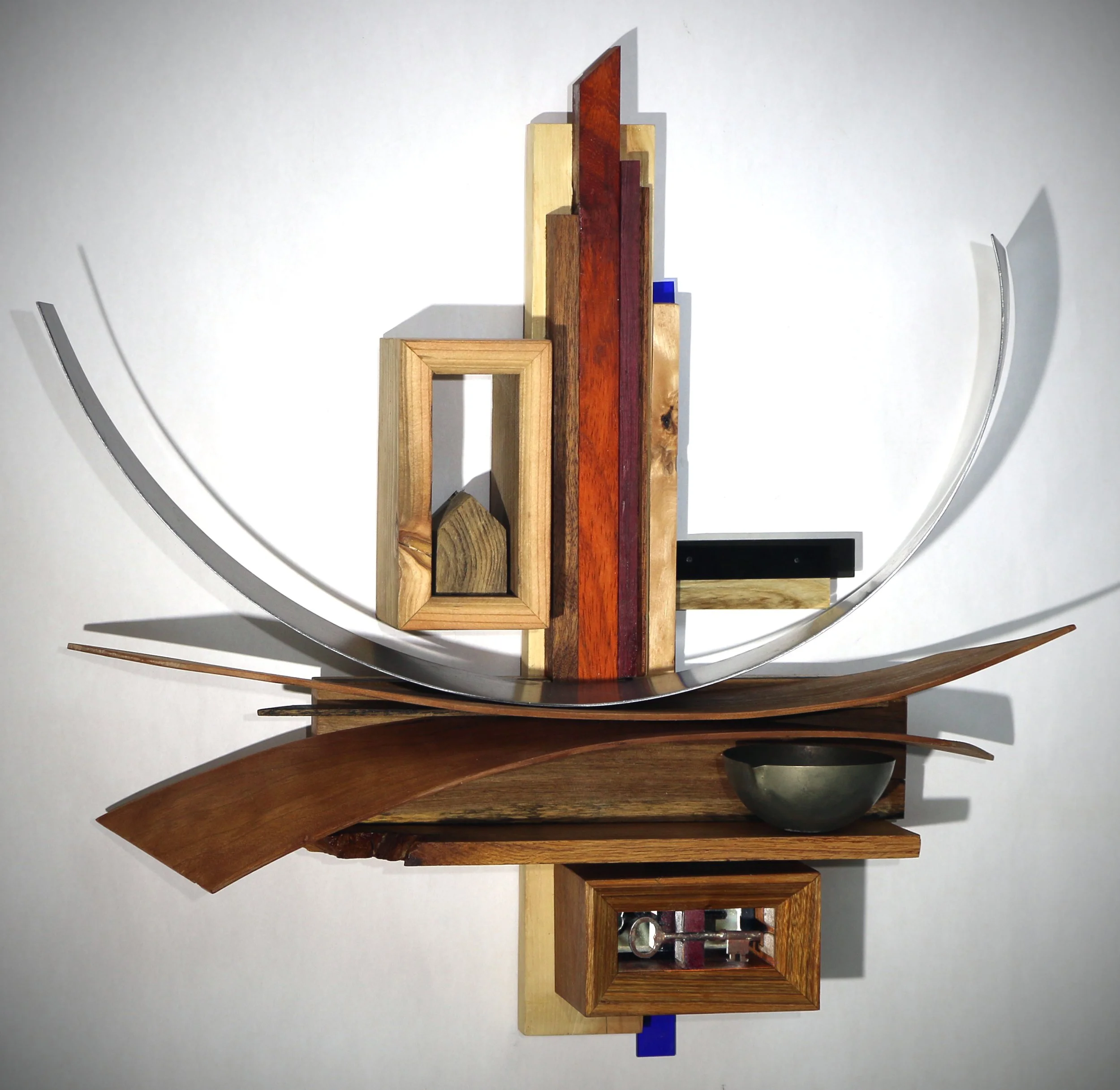

I was listening to some baroque classical music today and it made me think about my sculptures. The ebbs and flows of two independent melodic lines, each with their ornate phrases and tonality but each being equally important to the whole melody. It made me think about the combination of materials found in my sculptures. The curved element with their flowing nature and embodiment of motion working in harmony with the more structural linear components. In unison to create the foundation for the content that I’m trying to impart present.

Craig, your sculptural wall works often hover between objecthood and spatial proposition, asking the viewer to read balance, tension, and pause almost as sentences rather than forms. How do you understand the moment when material arrangement begins to function as language rather than structure?

This raises the timeless question that artist struggle with. When is a piece truly finished? As an artist, I’m not sure that we can ever say when it hits that point. There is always that lingering feeling that maybe there is one more mark you can make that will complete it. I believe we all eventually arrive at a moment where we know or sense when all is right with a piece. With my work, that point is generally when it appears conceptually complete and no more additions can be made without overcomplicating it. There is always that moment in time that the arrangement speaks to me, allowing it to function as a vehicle for communicating my ideas, thoughts or message. Engaging in a narrative with the audience.

However, the path to reach this point can be challenging. When developing a new idea for a piece, I layout the basic structure that will act as the framework. Through the use of both the curved and linear components, spaces or voids result creating areas in which I place objects. The hope is that the combinations of them will somehow create a valid story or commentary for the viewer. Being that there is a different symbol or history contained in each, it is difficult to assert what message has resulted.

In my studio, there are shelves of found object that I eventually plan to incorporate into my artwork. When I begin to integrate them into a project, I choose items that appeal to me based on their appearance. The lines that captivate me or their shapes and profiles. Equally important is the content they embody. I arrange several things together in the voids in hopes that some message or meaning will emerge. Although I inherently understand what these objects signify I have found that over thinking tends to convolute the objective of the piece or distort the content.

For the development of the context, I rely heavily on my subconscious or the intuitive process to resolve the particulars. This is where the mind holds, non-conscious memories, habits, and emotions. It functions as a memory bank storing past experiences. To readily access it we need to silence the interference. I do this by engaging in something other. Placing three things together in the piece and walking away to work on something else. By not intentionally thinking about it I allow mind or thoughts to wander and resolve the issue. When I come back, I usually look at the arrangement and say no. Switch out some pieces and start over. I eventually come to a point where all feels right.

Wood, steel, and acrylic appear in your practice not as neutral supports but as agents carrying memory, resistance, and translucency. How do you negotiate the ethical and poetic weight of these materials while allowing them to remain open to reinterpretation rather than fixed meaning?

As well as being used to make the basic structure or the foundation of my art, the materials I use possess a certain potential to convey commentary about our world or to add to the insights expressed held within my sculptures. The inferences behind using these different materials varies. The use of wood brings into the work a connection to nature. Fostering a feeling of warmth and vitality. With the steel, strength and longevity are implied while acrylics suggest durability and versatility. They lack a fixed meaning in that everybody has a different experience with or connection to these materials. Although the concepts or values embedded within them may not be readily apparent, they do have an emotional impact that we respond to that adds to our interpretation of the art.

I select the materials that I incorporate in my sculptures deliberately, considering not only about their visual appeal but also their origins. When I decide on a piece of lumber for a new piece, I choose a piece based on the color and the grain. The steel for the patina and the curve it holds. The acrylic for its color and ability to enhance sections of the whole piece. However, with all of these materials, there is an overriding issue of environmental responsibility. With the wood, there are certain ethical implications to the use of certain species such as the issues of deforestation or ecological destruction. For steel, the primary concern is the carbon footprint associated with its production. And acrylics there are issues with their environmental impact. Fortunately, where I buy my wood offers species that are farmed or sustainably sourced. As for steel and acrylic, I strive to remain conscious and careful in how I use them.

In college, with my final projects, I took old 2 x 4 pine and shattered them by dropping heavy weights on them. This revealed the inner structure of the wood, it’s heart. These were then glued together to form curves thus, in my way, returning them to their more natural or organic state. These early works were solely about the materials and forms that were created with them. And yet, the handling of these materials served as an exploration into both the formal side of creating art and the content hidden within the work. Not just a construction material but maybe now, a commentary on the industrialization of an organic substance that is used to build the structures we inhabit. The intent of these sculptures was to raise questions about the process of how we convert beautiful old-growth trees into linear lengths of dimensional lumber, stripping away all of their character.

But beyond that, the wood itself still has a story to tell. How each growth ring is a record of a point in the life of that tree, the curves that speak of where a branch or limb began, the colors often representative of the toxicity of the wood that it uses to fend off predatory insects or, locally, the blue in pine that indicates the bug that killed it

How do we balance the possible ethical issues in our material usage and the value of crafting something of beauty and of benefit to society? There needs to be a consideration between the art’s purpose and benefit to society. An understanding of the implications of each choice we make is a crucial step in creating art responsibly.

You have spoken about your early resistance to becoming an artist and the pivotal role of mentorship in redirecting your trajectory. How has that initial reluctance shaped your long-term relationship to making, particularly your refusal of predetermined drawings or closed outcomes?

That initial reluctance helped to develop a more realistic outlook to the idealized life of an artist. To formulate a more sensible or practical approach to my creative process.

Seeing the challenges faced by working artists trying to succeed and having two brothers in the arts and watching their struggles, I logically opted out of the field and pursued other endeavors. Seeking a change in my life, I returned to University and happened upon a teacher who saw within me my potential and encouraged it. I curse her to this day!! She became my primary mentor but that role was also shared by several of my teachers at UCD. The faculty were dedicated to their practice and had a strong passion for teaching. Their methodology as a group, was a more supportive and positive style to teaching. Recognizing potential and encouraging it, combined with a willingness and desire to pass on their knowledge of craft. They also knew when and how to give that push when faltering.

When I started taking art classes at UCD, the art world was nearing the end of an era where artists rejected the norms of artistic practice preferring to create art not intended to last. For creating more ephemeral work that prioritized the idea, process, or experience over making of a lasting, marketable object. For example, the Starn brothers use of Scotch tape to construct large-scale photographic collages. Their art was exemplary but not intended to last. I was fortunate to be part of a group of students at UCD who were of a similar mindset. It was an older group, a lot of us were in our thirties, whom already had a good knowledge of technique. We were rejecting the norm that existed then in that we believed in quality. The common belief that if you make something unattractive or poorly made, regardless of how strong your message is, no one will look at it.

Starting my career as an artist later in life proved to be both beneficial and challenging. The positives being that I didn’t have the burden of youth with its high expectations and pressure to be relevant or to be a success and thus allowing me to look positively on my growth and development. I also knew that the likelihood of achieving success in this field would be difficult at best. This helped me to focus on making art that I like and am proud of. It also helped me to establish a career where I could operate independently of public opinion, focusing on personal expression rather than validation.

I believe that all of this has shaped a different mentality or mindset about creating art than most. With the teachers I had and working with my brother in his studio and seeing their fervency, I developed an undeniable passion for creating. As to the refusal of closed outcomes, this foundation I have been given has led me to embrace the idea of the rejection of limitations. There is no end to the potential or possibilities or prospects of what we are capable of doing.

Many of your works are built through an intuitive process of laying out materials until a narrative emerges. How do you distinguish between intuition as genuine perceptual intelligence and intuition as habit, and how do you disrupt the latter in the studio?

Intuition comes to play in two areas of my process. The first is when the foundation or fundamental frame work is laid out. I always begin by laying out the wood or the steel on my work table until I sense or perceive a certain flow. The vibe that arises with the configuration of the elements or how the composition works. By design in that this is how I start most of my sculptures. It gives the impression that this is habitual but it is a routine based in my knowledge or understanding of the sense of motion and rhythm of the elements. However, perception is undoubtedly involved in that it takes a trained eye to recognize and comprehend the flow and the energy within the movement of these components. All of which comes from knowledge.

Studying Renaissance paintings and artwork in school taught me about composition. The arrangement that directs the viewer's gaze. How the arm points to the curtain which droops to the linear floor. The idea is two-fold. The artist wants to keep you, the viewer engaged in the work. They also want to lead you to a central point of the painting, often a statement or point represented by a depiction of symbolic laden objects. They were able to convey the message, narrative, or scripture to an illiterate populace since everyone understood the purpose or meaning behind those symbols. Understanding this, the layout process becomes instinctive or habitual but reliant on my insight that is based in what I have learned. I have learned to trust and rely on this ability

Perception comes more into play when I begin to place the objects into the sculpture. Every item that I include has an inherent symbolism or a latent history associated with it. When I group several of them together their meanings and histories converge together to form a narrative. Throughout this process, that story is not always clear to me. When I look at these objects, the knowledge or understanding of what the symbolism is or what those dormant histories are is there. It now becomes a matter of determining what the relationships are between the objects and what the narrative might be. This is not always going to be obvious. Here is where I have come to rely on intuition. At this point of my procedure, I put the items together and walk away and engage in some inane task. This allows my subconscious to work through that latent information to come to an interpretation that is valid. I will go thru these steps several times until it just feels right. There have been times when I go home still not understanding but sensing I have it right. When I come in the next day, there is this aha moment when I finally understand.

My creative methodology relies on and is influenced by the intuitive process whether it is perceptive or habitual. It plays such a significant role in how I work that it somehow feels habitual. That moment when the curves a feel just right, that they are generating the right energy, when the balance is correct giving transmitting that right amount of precariousness; when the energy of the objects is in sync. So it is hard to separate what is pure perception or what has become rote. Either way, it seems to working for me.

The recurring presence of houses, chairs, and everyday forms suggests a sustained inquiry into domestic memory and psychological shelter. In what ways do these motifs operate as collective symbols while still retaining the specificity of personal history?

I include this imagery or these forms because I am attracted to them and there is a meaning or value to me but also because they are universally recognizable. I think people are drawn to these images or icons because they are familiar with them and are not really thinking about the symbolism or the content they represent. When we go to look at works of art, I don’t think we go in with a purpose or an intent to come away with a deep profound message. With most art, our attraction is based solely on an emotional response to what we are seeing. Especially art without recognizable forms. We are attracted to it but can’t explain why. A visceral response to a stimulus that is felt on a base level. A gut reaction. When we view art that contains imagery that we know and can relate to, we don’t necessarily approach them with the intent to understand and yet we instinctively get it. We respond to the stimulus emanating from those objects. Memory or the recognition of the metaphor is triggered and we begin to comprehend.

Your sculptures are often described as metaphorical vistas, a term that implies both distance and immersion. How do you think about the viewer’s physical position in relation to the work, especially when the sculpture is fixed to the wall yet conceptually expansive?

I’ve always enjoyed watching people interact with my sculptures. Their contemplation of what they are looking at. Absorbing the content. The work has a tendency to draw viewers physically into it, to discover.

When creating a new sculpture, I think that I have a subliminal awareness of how the work is perceived from various physical positions. Using formal compositional elements, I attempt to draw the viewer in. At a distance, I think people are drawn to the sense of motion and balance. The tangible steel and wood curves giving the physical presence of that movement and when properly lit, a more subtle sense of flow from the shadows created on the wall. There is also a sense of balance to the sculpture that makes one look. Sometimes appearing precarious or unstable but with a sense of symmetry to bring order to the tension.

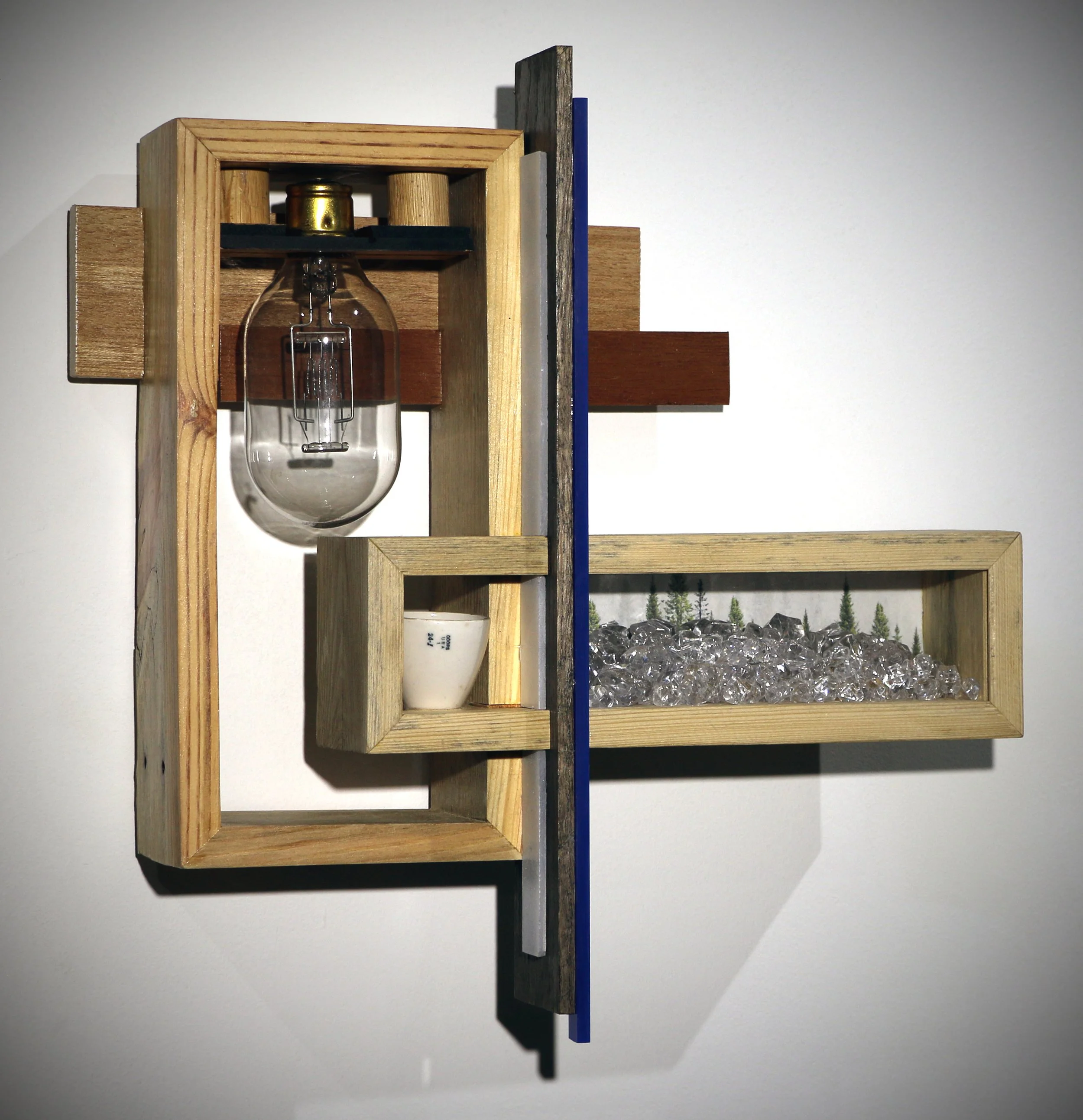

Drawn in, the viewer can begin to engage with content of the work. Being physically nearer, they are now able to see the forms and objects not clearly visible earlier. Reflecting on the objects included raising questions about their significance and trying to determine the content or value of what the artist is trying to covey. There are also some of my pieces that contain small, subtle elements hidden in niches, intended for the truly engaged viewer to discover.

Although typically attached to the wall, normally the realm of two- dimensional art, there is still a feeling of that you can engage with the work as sculpture. As with free standing pieces, by shifting one's perspective, its presence changes as one passes by the work.

Found objects in your practice seem to oscillate between reverence and reconfiguration. When working with multiples of the same object, how do you decide when repetition amplifies meaning and when it risks neutralizing the object’s history?

Part of my artistic practice involves the tradition of using multiples to form or create art. Where I combine several of the same item to make a cohesive piece. The aim is to create a singular object made from many by taking them out of context and transforming them. The altering of an everyday common object into something other than what they were originally intended for. Utilizing the linear visual aspects of the original item in combination to become a dimensional form and to challenge our perceptions and encourage us to see the beauty and potential in the mundane.

On a base or fundamental level, I like the idea of or concept of reverence as it pertains to this body of work. In the sense that we are seeing a value or beauty in our discards. As an artist, I think that I observe or look upon our world differently than most. Seeing a rusted steel panel for the variation of color and texture. And with simple objects, the lines or patterns that emerge within their shapes. It is my hope that these artworks get people to look upon the mundane in the same way.

Making art in this manner serves not just an aesthetic purpose but often holds a deeper significance. Taking into account the historical and cultural context embodied within the individual item, these artworks also become a platform used to address issues important to me. Subject like waste or the environmental impact of our disposable culture.

At some point, I was able to acquire a large amount of industrial sized incandescent lightbulbs. With the conversion to the use of LED lighting these were being discarded. The changeover being done for the benefit of the environment. The new lighting system offering a longer life span requiring less electricity and leads to lower air pollution. With fewer bulbs being manufactured and disposed of there is less waste. All for the long-term benefit of the planet. The irony being lies in the amount of existing inventory of bulbs heading to the landfill.

When using numerous identical items, is there the potential that their historical significance will be demeaned, negated or invalidated? Personally, I believe that a value still exists within the object and that its importance even becomes amplified. The history of the object does not get lost or neutralized but rather, it gets transformed. From a conceptual point, they evolve from a mere object, such as a lightbulb designed to illuminate a room to become a commentary on industrialization, mass production, waste. The presentation of these items in this manner, allows for a more complex, in-depth exploration of importance of the singular in respect to the many. Hopefully their historical importance gets multiplied and become more germane.

There is a potential for this loss of relevance as these objects age to the point where their original use is forgotten. In my smaller work, I sometimes use parts scavenged from vintage manual typewriters. Most people seeing these components do not recognize them but their curiosity sets in. They understand that it is of a mechanical nature but don’t grasp what exactly what it is or where it came from. Gradually, they start to speculate as to what its original purpose might have been. While the history may have been obscured it has been be replaced by the innate inquisitiveness of human nature and the desire to comprehend.

There is a quiet but persistent sense of movement in your work, created through curved steel, layered planes, and subtle asymmetries. How important is the idea of temporal movement in your sculptures, and do you see them as frozen gestures or ongoing actions?

I look at my sculptures as points in time. A mere moment of an event that we are privileged to observe. A fleeting second that might never recur. This then gives us a chance to explore the connection between the objects. To identify my message or to develop an interpretation of the content that is relevant for them.

The curved elements present in my work take on several different interpretations or references. Utilized as a compositional tool to keep the viewer engaged, movement is used to steer the viewer in their journey giving them direction, providing a means of connecting the different components to create an association. Leading the eye in hopes that a story will evolve. They can also elicit an emotional response, deep seated in our evolutionary being. Wind buffering off the house or blowing across the open spaces of the plains. The curved material creating a feeling of turbulence or chaos. Within this noise, the more sheltered sections of the sculpture appear calm, giving them a sense of tranquility. In other pieces I utilize the physical properties of the material to evoke a feeling of shelter or being a protective barrier. A safe haven for that house.

I recently had a conversation with a gentleman about the energy that he felt emanated from my work. As the conversation went, I found that his perception was much different than mine. I was thinking more about my emotional level at the time of creating the work and how it impacted or was embodied in my art. I have always found that how you feel while creating usually makes its way into the art and people respond to that. If you enjoy what you do, people sense a level of happiness. Conversely, if you are mad at the world, that anger becomes apparent and integrates into the piece.

From his perspective he said that he was drawn to what one might call the mystical or spiritual energy, the aura. He pointed out to me how the flow of the curves in one of the sculptures had a calming energy to it. The horizontal flow of the elements for him was very relaxing or calming, putting him at ease. In another piece, he found that the movement had a very positive and uplifting feel to it and the way the curves functioned, he was always drawn to a central point of the sculpture where it was the strongest. I’m not sure that I had really thought of my art in such terms so it was very illuminating.

Your recent explorations of light and color mark a departure from earlier material emphases while remaining conceptually aligned. What prompted this shift, and how has the introduction of light altered your understanding of depth, shadow, and perceptual truth?

My palette has always been rather muted relying on earth tones. At some point I felt that in order for the level of my art to improve that I needed to do something to enhance the work. About that time, I saw a show of the art of Pascal Piermé. Very much a formalist, relying on form and line to create his works. He too uses a rather neutral palette of greys and browns but to this he adds minimal lines or splashes of color used to lead the eye and to enliven the piece. I began experimenting with this idea by adding lengths of fluorescent acrylics. The work instantly became more dynamic and interesting. As with the other elements in my work, I use these splashes of color to aid in define the spaces

I also began looking into the effects of color on our psyche. How they evoke emotions or shape moods and influence behavior. Reds representing passion, intensity, danger and anger or blues associated with tranquility, calmness, and sadness or nostalgia. I’m still trying to determine what the effect of color in my sculptures is. I’m still exploring this concept and have pushed the idea or experiment further with the addition of light and how it affects our moods. Taking us from feelings of serenity to tension.

One of my latest installations was an attempt to play with this concept. The premise of the piece was about altering perception of space and mood by focusing on color and its qualities. How the viewer responds or reacts to certain colors. I made a room out of black fabric with a white chiffon hung inside. The dimensions were around 10 by 12 by 8. Large enough to walk into. It was lit by larger lights that would change color. When immersed within this structure, how were the moods different. Did people’s mood differ or transform with each color change. Not sure about the results but I enjoyed watching people become immersed in the art.

My initial excursion into using light as a medium involved experimenting with video. After seeing a show of Bill Violas work, I was drawn into his use of the media. How he used it in a manner reminiscent of static visual art, like a painting in motion. In contrast, most video works I had previously encountered felt more like films displayed in a gallery setting. These thirty-minute displays were treated as an artwork that you were expected to sit through in order to understand. Viola and others use video as their format they use to express a concept or a point of view but they keep them relatively brief. These works communicate their point or content in a timely and succinct manner which allows you to move on to the next piece.

Back in the studio, I came up with idea of abstracting video, how to take that imagery and deconstruct it into simple movement of color. Projecting the video into a column of rice paper or through a two-inch thick piece of acrylic. Even getting to where I reduced the imagery to pixels by projecting it through optic fiber.

A friend of mine, a local artist, Colin Parson, makes large scale light works that transforms the rooms in which they exist. Seeing his use of light sparked my curiosity as to how I would incorporate this medium into my work. I am also interested in the symbolism or psychology of color and its effects on us. Combining light with the colored acrylic or by just using the hues of the LED’s helped me to explore these ideas. I have also used light as a highlighting element or for its transformative qualities. With one series of sculptures, I heated sheets of acrylic in an oven. Taking these pliant rectangles of plexi I would bend or fold them into curvilinear panels. I then arranged the LED’s behind them where the light would only be visible on edge. This body of work focused on the movement inherent in the material. Using the light to highlight the edges helps making that sense of movement more dynamic, accentuating the spatial nature of that motion. Again, moments in time captured.

The use of light has allowed my sculptures to elaborate on the idea of the spatial world we exist in. My work already uses depth and shadow to expand the volume of the sculpture. The addition of light as an element helps illustrate this. It also introduces the idea of temporal existence into the work. In an oblique way, we can look at these objects and their symbolism in relation to the perception of time.

You often describe your hope that the work might encourage viewers to look differently at their everyday surroundings. How do you balance this aspirational generosity with the risk of overdetermining the viewer’s experience?

I had a teacher who was a conceptual artist himself so had a unique viewpoint about the inclusion of content in one’s art. I think his most valuable lesson was not that you had to have content but how to see and understand the substance and depth of your work.

In my art, I feel the need to make commentary on issues significant and relevant to me or just to articulate my thoughts about the state of our world and our impact on it. My commentary tends to be somewhat ambiguous, as it is told through objects. These are things that I have a connection to or maybe a unique understanding of their symbolism.

Working with content-laden objects, I learned early on that everybody has a different connection to or history with them and so can’t help but to develop their own interpretation. It becomes a matter of allowing them to do so.

I have had patrons who come up to me to inquire about the meaning of a specific piece. I respond politely, declining to provide an explanation and instead encourage them to revisit the sculpture and share their own interpretations with me. Friends of mine are surprised with this approach feeling that I should just tell them. Soon enough though, these people return and tell me their perspectives. I always love to hear what their thoughts are. Rarely the same as mine but it is so interesting to hear their viewpoint. Instead of me then dictating the meaning to them, we get to have a discussion about the art and intent behind the work.

Influences such as Lorre Hoffman, Brian Dreith, Kevin Robb, Louise Bourgeois, and Louise Nevelson appear less as stylistic references and more as ethical positions toward making. What have these figures taught you about endurance, reinvention, and responsibility within a lifetime of practice?

Of all of the people who have influenced me or had an effect on my career, the common trait they hold is the love they have of art and the passion for creating. They are also know for the constant growth in their artworks and their methodology always looking for new approaches to their creative process. Always finding new ways to look at their creations.

With both Louise’s, I have always been in awe of the longevity of their careers. How they felt that they could never stop being an artist. I always find humor in young artists who assume that they are going to be successful immediately and get frustrated when this does not happen. I have them look at these creators who not only pursued a long career but willing tried new and different ways to their approach.

And there is my brother Kevin who had a massive stroke at 49 leaving him muted and physically incapacitated. Working through the trials, the difficult times of his recovery, he was still focused on his art. His determination and grit to continue creating still motivate me. Twenty plus years later, he is still at it.

There were times where I would get frustrated with my progress and would start to question my motivation behind selecting art as a career. I look to the lesson I learned from my teachers and to these artist’s and basically tell myself to get over it and to get back into the studio.

Teaching and working with students has clearly informed your perspective on artistic labor and its realities. How has articulating the difficulties of an artistic life clarified or complicated your own commitment to the studio?

I was most fortunate and after graduating, I was able to get a job at the University of Denver as the sculpture shop tech working with Lawrence Argent. In theory, my job was to maintain the facilities and make sure the students had a safe place to work in. From the first day though, Argent pulled me into the classroom as an assistant. This eventually morphed into a job where I became increasingly involved. After he conducted the demonstrations on the various processes, it became my responsibility for making sure that they learned the techniques properly. This arrangement allowed him to focus on teaching content and concept. Outside of class, I would work closely with the students to complete their projects. During this time, we would often get engaged in conversations about art and our place in that world.

One story that I often relate to people about my time at DU was when students would ask about my experiences as a professional artist. They came with hopes of being regaled with stories of the fabulous life I led. Instead, they got to hear about the trials and tribulations of being a sculptor. How I worked with them all day, closed the shop and then worked in my studio for a few hours. Come Saturday, it was another ten hours of studio time. Sundays were for playing soccer, enjoying a few beers, and eventually falling asleep, only to start again on Monday. I always got a laugh from the expressions on their faces. Totally aghast. Surprised that I didn’t make it sound more exciting. I would always end by saying that, of all the things that I have done in life, being an artist has been by far, the most rewarding and fulfilling experience I have had.

There is an old proverb I once read “As you teach, you learn” Through this job, I was able to pass on my knowledge and skillset pertaining to the technical side of sculpture. How to weld and manipulate metal together to create objects. How to transform an ordinary piece of wood into their idea. The rewards were simple, watching them get excited and their sense of accomplishment when they saw that metal melt together to make their first weld or getting over the fear of the saws to change the wood into art. I think what I got from them and took into the studio was that excitement and energy.

Having a full-time job there and trying to maintain a career as an artist, I had to develop a disciplined studio practice. I was very fortunate in that I was given a small work space of my own and was able to use the facilities to make my sculptures. The problem being that I could not leave my materials out since this is where we taught. I had to become very organized and methodical in my practice in order to get things accomplished. Practices that I continue to employ in my studio today.

Your work often creates spaces within spaces, framing voids, compartments, or thresholds that feel both architectural and psychological. How do you conceive of emptiness as an active component rather than a lack?

When I was in school and had the room to build them, my sculptures were larger and very formalistic in nature emphasizing the material and the shapes that developed. When I had to down-size my studio, I found it necessary to adapt my art to fit my workspace. Having this interest in found objects and their inherent meanings, I wanted to start making sculptures that highlighted these elements. I needed a way to organize or display them so I started making boxes. An issue soon arose in that people appreciated the boxes I made but didn’t know how to showcase them. This led to me modify them so that they could hang on the wall. The box format eventually exploded into multi-layered structures that allowed me to display several objects. Each item was given a space of their own allowing for an appreciation of their individuality or relevance. By placing them in proximity, narratives result through the combination of their symbolism.

The spaces or voids within the overall structure became as pertinent as those that had a physical purpose of containment. With the inclusion of spatial elements in my art, the attention of the viewer has a tendency to moves from one space to another. Thus giving the voids as much weight as those that act as containers or receptacles.

I look at these spaces or voids as an essential part of the work, an essential component of the content. They become a place of contemplation or reflection. They evolve into a point for pause where one can meditate on potential or what could be. The endless possibilities. But they also are about the idea of absence. Questions arise as to why it is empty, what was there or should be there.

From a physical standpoint, these voids also contribute to the feeling of equilibrium. Often the value or relevance of these gaps being more of a structural thought process. Meant to convey a sense of balance or instability or to add emotional weight. How precarious the nature of the world is. And yet it still evokes the question as to why it exists and what could be.

As contemporary institutions increasingly embrace spectacle and escapism, how do you position your work in relation to attention, slowness, and contemplation without retreating into nostalgia?

I view this new movement in art as being simply a form of entertainment or merely a diversion or distraction. A vacuous and vapid void into which to disappear. An essential thing in these times.

I tend to be rather tough when it comes to my views on art. My belief is that art must elicit some form of a response whether it be positive or negative. One should come away feeling happy, elated, excited or irritated, even angry. Something.

When this trend first started, there was an exhibition in town showcasing five of these installations in the gallery. Excited, because I love installation art, I decided to visit. I walked through each piece taking the time to observe what the artists had created. When finished I stopped to contemplate what I had just seen. I was shocked at my lack of response to the entire body of work. An uneasy feeling of indifference.

One definition of installation art is that it is an “immersive experience where viewers enter or walk through the artwork, becoming active participants rather than passive observers.” From that point of view, these experiential works succeed in that we participate by walking through them but are we actively engaged or just observers.

But therein lies their value. In the chaotic times that we live in, there is a need to disappear. To find a place where you can enter and simply enjoy without expectations.

Through my artworks, it is my hope to encourage people to stop. To pause and reflect on what it is that they are viewing. To become that active participant.

My approach is to create art that is not only well-crafted and aesthetically pleasing but also conveys a narrative. Something that is pleasant to look at, makes you smile or infuses some positive energy into your environs. That it can also be a source of ideas and act as a catalyst for thought. Art that can inspire by sparking the imagination or to challenge perceptions I enjoy watching people contemplating my sculptures. Slowing down to process or evaluate. Diligently trying to figure out what it means. I am never sure what they are thinking but it is fun to see their curiosity engaged. Ultimately, my aspiration is that the interpretation viewers walk away with either leaves them inspired or contemplative. And yet, I believe that even if the content is not immediately apparent or resonates with a viewer, the sculpture can stand on its own as an object of beauty that still evokes an emotional response.

Looking toward your upcoming fundraiser project for Pirate Contemporary Art, how are you thinking about audience, context, and purpose differently when a work is embedded within a communal or philanthropic framework rather than a traditional exhibition setting?

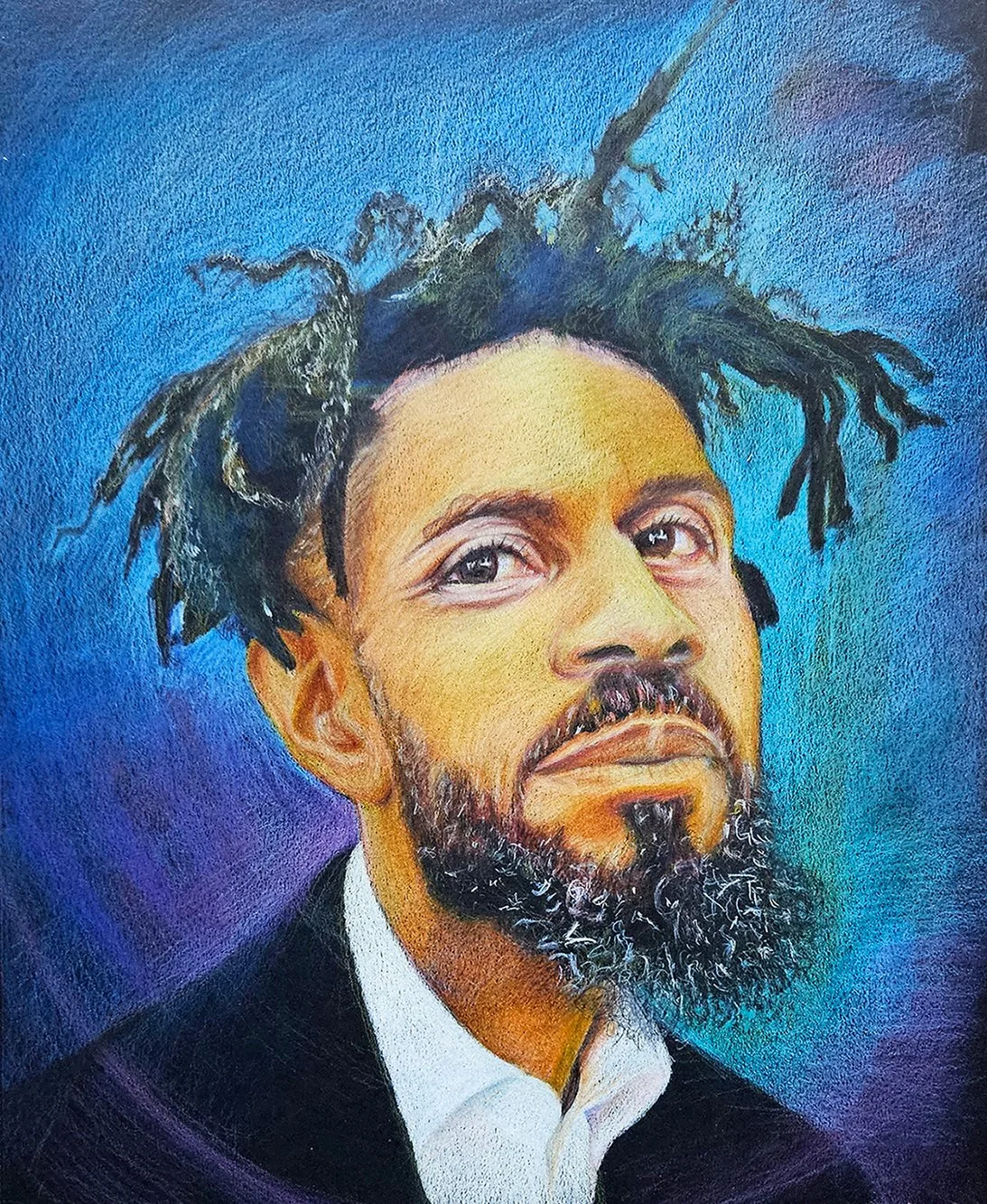

We had an empty show slot in our calendar and decided to take advantage of it and hold a fundraiser. Always trying to get our members to try something new and different, I came up with the idea of The Alter Ego show. Where we would all make art that would takes out of our comfort zone. Something that our doppelgänger’s would create.

When doing events like this, some thought does go into making a piece that is thematically correct but it still comes down to making art that I am proud of and want to include. The communal framework becomes important during the installation of the show. How to balance the different styles and personalities along with the strengths and weaknesses of each piece into a cohesive show that gives equal weight to all of the artworks.

A Point on the Surface

Arias thought vanished yet linger

As wind in dry grass

Cohesion

Cummulus

Ever and a day

For want of a candlestick

Hole in my shoe

Illusion of the familiar

In the night so still

Like a Dog, Barking at Heaven

Small Things That Can Alter Perceptions

The Butterfly Effect

The Path Taken