Annette Tan

Annette Tan’s paintings unfold with the quiet authority of a life lived between continents, between traditions, and between epochs of artistic consciousness. Born in China and later settling in the United States in the late 1950s, she represents a generation shaped by migration, adaptation, and a persistent search for visual language. Her artistic practice, which began in earnest in the mid-1990s, does not present itself as a sudden or radical rupture, but rather as a gradual cultivation of sensibility. Over time, this cultivation has yielded a body of work distinguished by chromatic warmth, atmospheric lyricism, and a sincere, contemplative engagement with nature.

Tan’s paintings do not attempt to disrupt the historical narrative of painting through shock or conceptual provocation. Instead, they participate in a quieter, yet equally significant dialogue: the continued relevance of beauty, harmony, and reverence in a contemporary art world often dominated by irony and fragmentation. In this respect, her work may be understood as a subtle form of resistance, one that restores the viewer’s capacity for contemplation. She paints not to declare novelty, but to reaffirm the enduring presence of the natural world as a source of spiritual and aesthetic insight.

Her recognition as a listee in the seventy-fourth edition of Who’s Who in America signals the breadth of her professional presence. This distinction, alongside numerous exhibitions and awards, reflects not only technical accomplishment but also the sustained visibility of her work across diverse cultural contexts. From exhibitions in the San Francisco Bay Area to international presentations in Paris and Austria, her career traces a trajectory of steady expansion, mirroring the gradual unfolding of her painterly language.

At the core of Tan’s practice is a dialogue with the legacy of the old masters. Her compositions reveal a careful attention to tonal balance, atmospheric perspective, and compositional clarity. One is reminded, in particular, of the quiet lyricism found in the late landscapes of Claude Monet. Yet the comparison is not merely stylistic. Where Monet dissolved form into light, Tan tends to preserve the integrity of objects while softening their contours, creating a synthesis between structure and atmosphere. Her brushwork retains a sense of solidity, even as color fields shimmer with subtle variations.

This synthesis becomes especially apparent in the painting “Birds of Paradise” (2012). The composition isolates the exotic flower against a dark ground, allowing its sculptural structure to emerge with clarity. The petals, rendered in vivid reds and blues, project outward like gestures of flame or wings in mid-flight. The surrounding leaves, painted in luminous greens, form a soft halo around the central bloom. Here, Tan demonstrates a sensitivity to chromatic contrast that recalls both botanical illustration and modernist color theory. The flower appears almost emblematic, not simply a botanical specimen but a symbol of vitality and transcendence. The painting suggests a moment of revelation, as if nature itself were offering a brief glimpse into the logic of creation.

In “California Poppy” (2012), the artist shifts from the singular motif to a panoramic field. The composition stretches horizontally, allowing the eye to wander across a sea of red blossoms. Two trees punctuate the horizon, their forms softened by atmospheric haze. The sky recedes into a pale gradient, suggesting the gentle fading of daylight. This painting resonates with the pastoral tradition, evoking a sense of quiet abundance. The poppies, rendered in warm hues, appear almost as a chromatic carpet, transforming the landscape into a field of luminous color. The painting does not dramatize nature; instead, it offers a meditative encounter with its rhythms.

“Flower and Lace” (2011) presents a still life that recalls the intimate domestic scenes of seventeenth-century painting. A vase overflowing with blossoms stands on a draped cloth, accompanied by a teacup and scattered petals. The composition balances vertical and horizontal elements, guiding the viewer’s gaze through a carefully orchestrated arrangement. The drapery, painted in soft blues and whites, creates a luminous backdrop against which the flowers appear to float. Here, Tan’s brushwork becomes more tactile. The petals are suggested through small, energetic strokes, giving the bouquet a sense of movement and freshness. The painting embodies a philosophy of attention: the idea that beauty resides not in grand spectacle, but in the quiet arrangement of everyday objects.

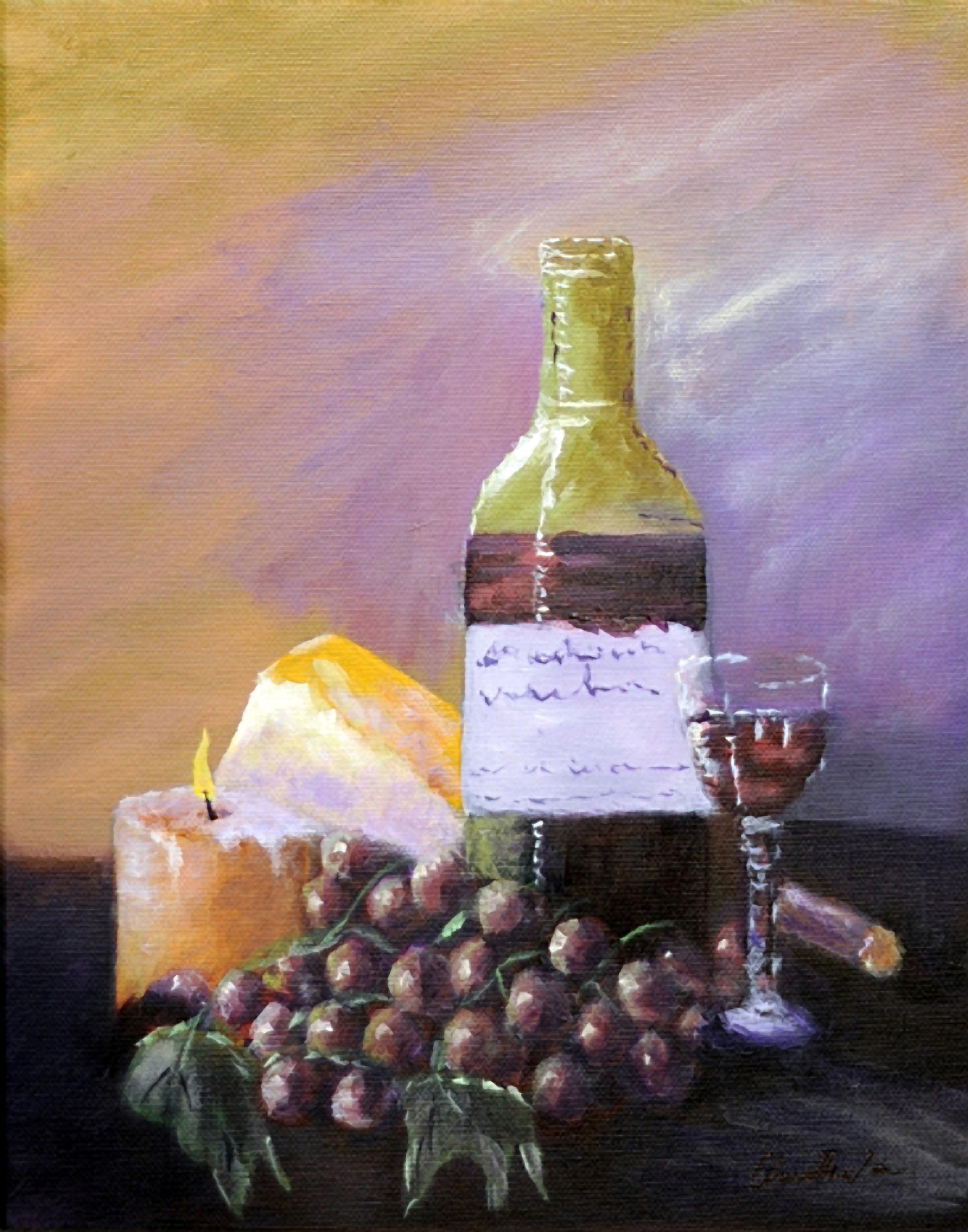

In “Harvest” (2012), the still life expands into a symbolic tableau. A bottle of wine, a cluster of grapes, a candle, and a wedge of cheese are arranged on a dark surface. The candle’s flame introduces a small, flickering light source, casting warm reflections across the objects. The grapes, painted in deep purples, appear almost translucent, while the bottle’s surface catches subtle highlights. This painting resonates with the tradition of vanitas, though its tone is not somber. Instead, it suggests gratitude and celebration. The objects become metaphors for sustenance and communion, echoing the artist’s spiritual orientation. The composition invites reflection on abundance and the cyclical nature of life.

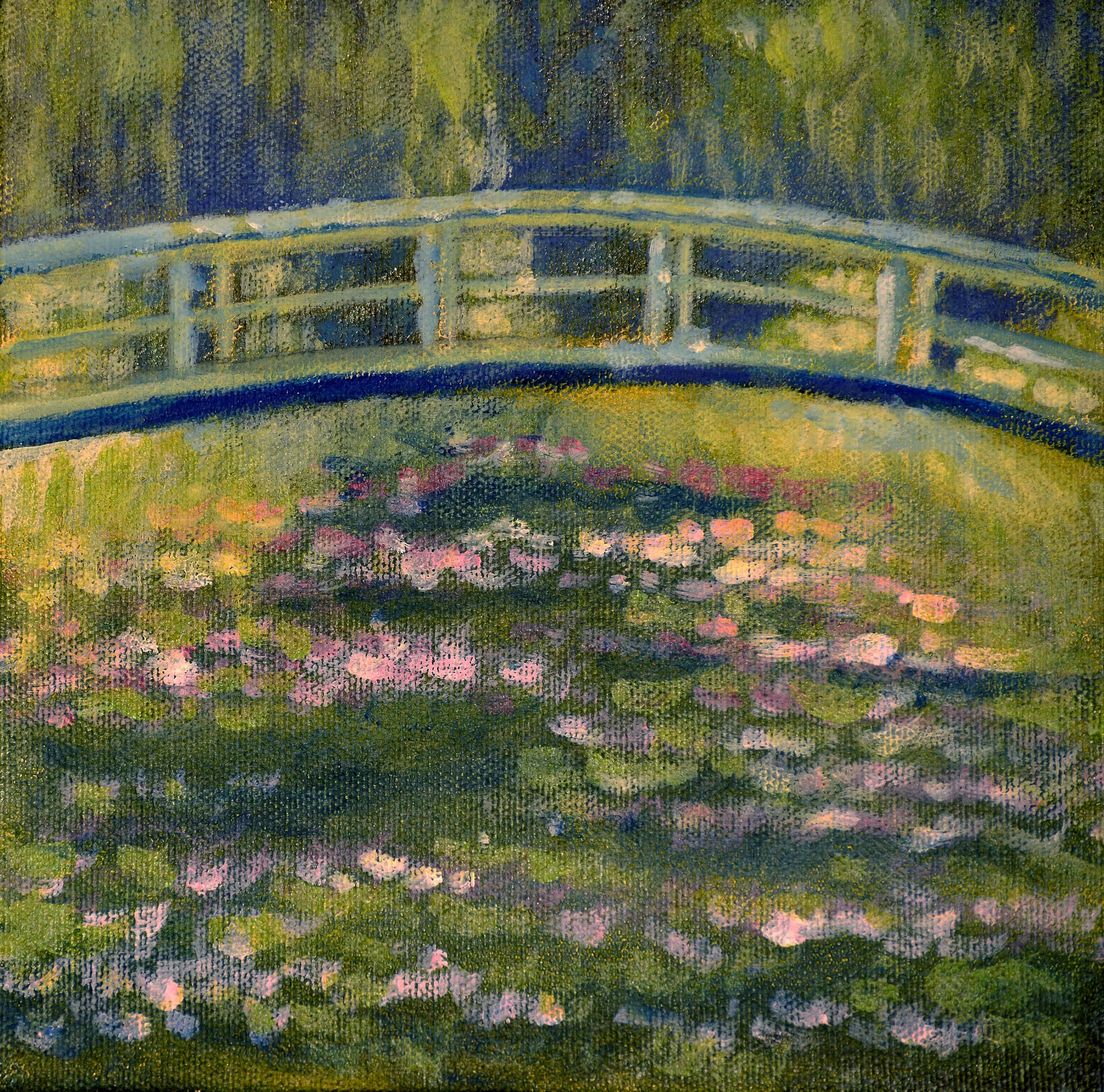

Tan’s engagement with art history becomes more explicit in “Japanese Bridge” (2012). The small, square canvas presents a curved bridge arching over a pond filled with water lilies. The composition clearly recalls the iconic motif associated with Monet’s garden at Giverny. Yet Tan’s interpretation is not a mere homage. Her palette leans toward cooler greens and blues, and her brushwork emphasizes the texture of the surface. The bridge appears almost suspended within a dense field of color, as if emerging from memory rather than direct observation. The painting suggests a dialogue across time, linking the artist’s contemporary practice with the legacy of Impressionism.

This dialogue continues in the two paintings titled “Lily Pond” (2012). In the first, the lilies float on a dark, reflective surface. The flowers, rendered in pale pinks and whites, punctuate the green expanse of water. The composition is quiet, almost minimal, emphasizing the stillness of the pond. In the second version, the lilies appear more dispersed, with larger areas of open water. The brushwork becomes softer, the colors more subdued. Together, these two works demonstrate Tan’s sensitivity to variation. She treats the same motif as an opportunity for subtle exploration, adjusting tone, composition, and texture to create distinct emotional registers.

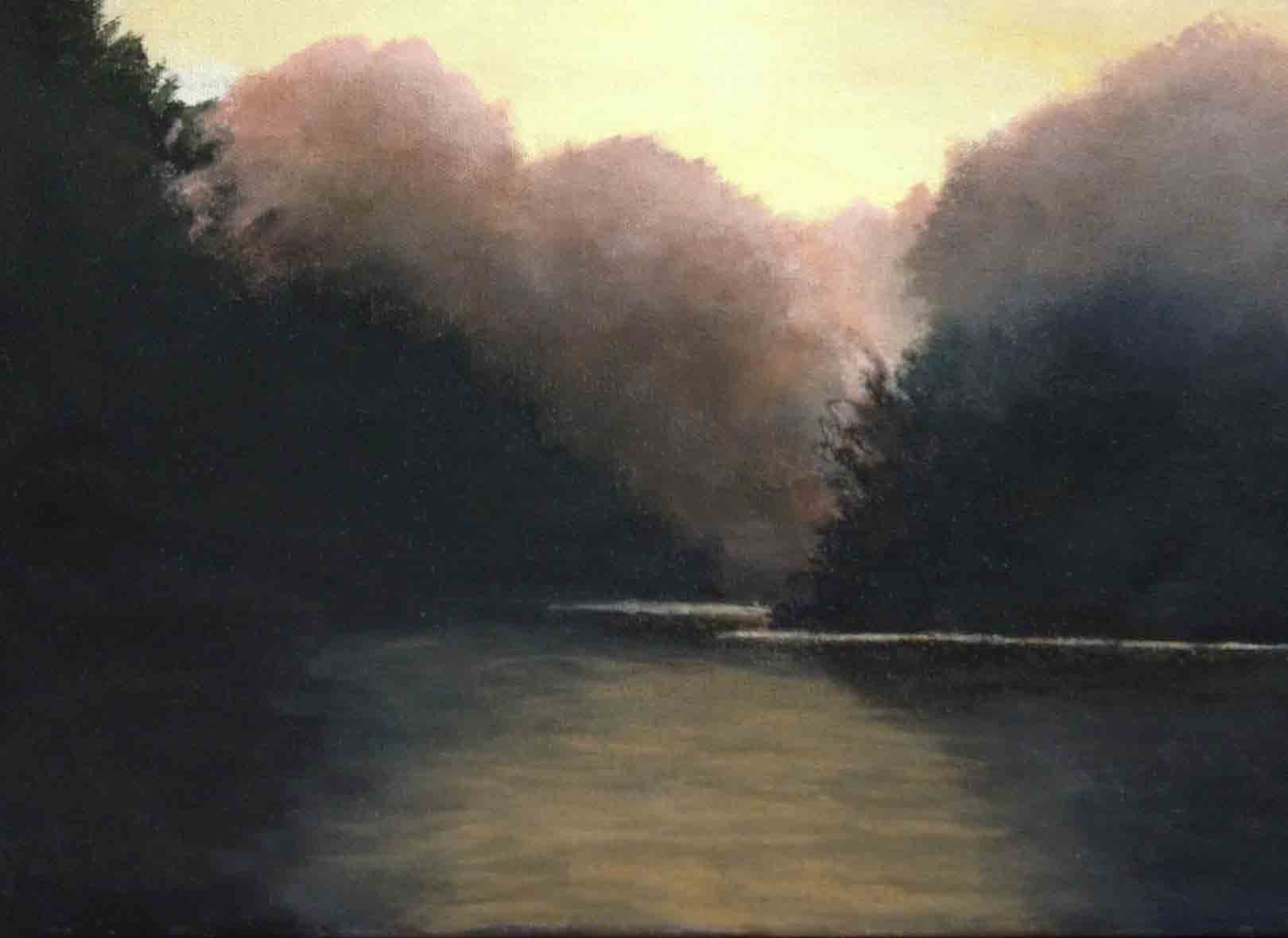

A shift in mood appears in “Misty River” (2018). The painting depicts a river winding through a landscape enveloped in soft haze. The trees along the banks are reduced to dark silhouettes, their forms dissolving into the mist. The sky glows faintly, suggesting the first light of dawn or the last light of dusk. Here, Tan’s palette becomes more restrained. Blues, grays, and muted greens dominate the composition. The painting evokes a sense of quiet introspection. The river becomes a metaphor for time itself, flowing silently through the landscape. This work reveals the artist’s capacity for tonal subtlety and atmospheric depth.

In “Vilagio” (2010), Tan returns to a brighter palette. A winding road leads the viewer’s eye through a landscape dotted with small houses and fields of red flowers. The composition is structured around the gentle curve of the road, which guides the viewer toward a distant horizon. The sky glows with a soft, golden light, suggesting early morning. The houses, with their warm roofs and pale walls, appear almost idyllic. This painting resonates with the tradition of pastoral landscapes, yet it retains a contemporary sensibility through its simplified forms and vibrant colors.

Across these works, Tan’s philosophy becomes increasingly apparent. Her paintings are not simply representations of nature; they are acts of devotion. The artist often speaks of her inspiration as arising from the beauty of God’s creation. This spiritual orientation manifests in the calm, balanced compositions and the luminous color harmonies that characterize her work. The paintings invite contemplation rather than analysis. They ask the viewer to slow down, to notice the subtle interplay of light and color, and to experience the world as a place of quiet wonder.

In the context of contemporary art, where conceptual strategies often dominate, Tan’s work occupies a distinctive position. She does not seek to dismantle the language of painting, nor to ironize its traditions. Instead, she affirms the continued relevance of painterly skill and aesthetic pleasure. Her work suggests that the pursuit of beauty is not a retreat into nostalgia, but a meaningful engagement with the world. In an era marked by rapid technological change and social fragmentation, her paintings offer a space of calm and reflection.

Her membership in the National League of American Pen Women, along with her participation in numerous exhibitions across the United States and abroad, underscores her commitment to the artistic community. The international presentation of her work, including recent exhibitions in Paris, situates her within a global network of contemporary artists. Yet her paintings retain a sense of personal intimacy, as if each canvas were a small, self-contained world.

If one were to position Tan within a broader historical lineage, the comparison with Monet remains particularly illuminating. Like Monet, she is deeply engaged with the effects of light and color. Yet where Monet’s late works verge on abstraction, Tan’s paintings maintain a stronger connection to recognizable forms. This balance between abstraction and representation allows her work to resonate with a wide audience, bridging the gap between historical tradition and contemporary sensibility.

Ultimately, Annette Tan’s paintings remind us that the language of painting remains a living, evolving form of expression. Her work does not rely on spectacle or theoretical complexity. Instead, it draws its strength from sincerity, technical skill, and a deep appreciation for the natural world. In this sense, her art contributes to a broader cultural conversation about the role of beauty and spirituality in contemporary life.

As a listee in the seventy-fourth edition of Who’s Who in America, and as an award-winning artist whose work has been exhibited internationally, Tan occupies a respected place within the contemporary art scene. Her paintings offer a quiet counterpoint to the noise of the present moment. They invite the viewer to pause, to look closely, and to rediscover the simple, enduring pleasures of color, light, and form.

In the end, her work stands as a testament to the enduring power of painting to articulate the subtleties of experience. Through landscapes, still lifes, and floral compositions, she constructs a visual language rooted in tradition yet open to contemporary interpretation. Her art does not shout; it speaks softly, but with clarity and conviction. And in that quiet voice, one hears the echo of a long and noble history of painting, carried forward into the present with grace and sincerity.

To situate Annette Tan more precisely within the long continuum of painting, one might draw a sustained comparison with Claude Monet, not as an exercise in simple stylistic alignment, but as a means of understanding how her work participates in the historical logic of pictorial modernity. Monet’s achievement was not merely the invention of a new style, but the reorientation of painting toward perception itself. He displaced the authority of narrative and academic subject matter in favor of the fleeting encounter between light, color, and atmosphere. His late water lily paintings, in particular, dissolved the stable coordinates of space, transforming the canvas into a field of sensory immersion.

Tan’s work, though grounded in a different historical moment and cultural context, reveals a comparable attentiveness to the experiential qualities of nature. Where Monet sought to capture the transient effects of light across the surface of water, Tan approaches the natural world with a similar reverence for its luminous and chromatic subtleties. Her lily ponds, bridges, and mist-laden rivers echo the compositional motifs of Monet, yet they do not merely replicate them. Instead, they translate those motifs into a contemporary visual language marked by clarity, balance, and a renewed sense of structure.

In Monet’s late works, the horizon line dissolves, and the viewer is enveloped by the pictorial field. Tan, by contrast, tends to preserve the compositional stability of the scene. Her bridges retain their architectural clarity, her ponds remain legible as spatial environments, and her landscapes maintain a coherent sense of depth. This distinction is significant. It suggests that while Monet pushed painting toward abstraction, Tan operates within a synthesis of representation and painterly expression. She inherits the Impressionist sensitivity to color and atmosphere, yet she reintroduces a structural coherence that reflects both classical training and a contemporary desire for visual clarity.

This balance between atmospheric freedom and compositional order positions Tan within a lineage that extends beyond Impressionism into the broader history of landscape painting. Her work carries echoes of the Barbizon School, of the pastoral serenity found in Corot, and even of the quiet devotional quality present in certain Dutch still lifes. Yet it is the comparison with Monet that proves most illuminating, because it highlights the way her paintings engage with the fundamental questions of modern art: how to represent perception, how to translate fleeting experience into pigment, and how to reconcile the materiality of paint with the immateriality of light.

The importance of Tan’s art in contemporary society becomes clearer when viewed through this historical lens. In a cultural environment increasingly saturated with digital imagery, speed, and distraction, her paintings offer a counterpoint grounded in slowness, observation, and tactile presence. Monet’s work once responded to the transformations of the nineteenth century—the rise of industrialization, the expansion of urban life, and the shifting rhythms of modernity. Tan’s work responds to a different set of conditions: globalization, technological acceleration, and the fragmentation of attention.

Her paintings restore a sense of continuity with the natural world. They remind viewers that perception is not merely a mechanical act, but a form of contemplation. The stillness of her lily ponds, the glow of her landscapes, and the quiet abundance of her still lifes function as visual meditations. They encourage a slower mode of seeing, one that resists the relentless pace of contemporary life. In this sense, her art carries social significance. It provides a space for reflection, offering viewers a moment of respite from the visual noise that surrounds them.

Furthermore, Tan’s personal history enriches this significance. As an artist born in China who later established her life and career in the United States, she embodies a cross-cultural perspective that resonates with the global character of contemporary art. Her work does not explicitly address themes of migration or identity politics, yet it quietly reflects the synthesis of cultural experiences. The serenity of her landscapes and the harmony of her compositions suggest an underlying philosophy of balance and integration.

In contemporary art history, where conceptual frameworks and critical theory often dominate discourse, Tan’s work serves as a reminder of the enduring relevance of painterly tradition. She demonstrates that the language of color, light, and form remains capable of expressing profound ideas. Her paintings do not rely on textual explanation or theoretical scaffolding. Instead, they communicate directly through visual experience.

This directness is not a limitation, but a strength. It reconnects painting with its fundamental capacity to evoke emotion, memory, and spiritual reflection. Just as Monet’s water lilies transformed the act of looking into an immersive experience, Tan’s paintings transform everyday scenes into moments of quiet revelation. Her art suggests that beauty is not a superficial quality, but a form of knowledge—a way of understanding the world through the senses.

In this respect, her work contributes to a broader revaluation of beauty within contemporary art. For much of the late twentieth century, beauty was often treated with suspicion, associated with decorative excess or ideological complacency. Yet in recent decades, there has been a renewed interest in the aesthetic dimension of art. Tan’s paintings participate in this shift. They assert that beauty, far from being trivial, can serve as a vehicle for contemplation, empathy, and spiritual awareness.

By situating her practice within the lineage of Monet, one can see how her work extends the trajectory of modern painting into the present. She does not seek to revolutionize the medium, but to sustain its capacity for meaning. Her paintings stand as quiet affirmations of the enduring power of light, color, and natural form. In doing so, they secure her place within the evolving narrative of contemporary art history, not as a radical disruptor, but as a custodian of a tradition that continues to speak to the human condition.

Annette Tan’s work stands as a quiet but enduring affirmation of painting’s relevance in the present moment. Her art does not seek to compete with spectacle or conceptual complexity, nor does it rely on rhetorical gestures to assert its significance. Instead, it returns to the essential conditions of vision: the encounter between light, color, atmosphere, and the living world. Through landscapes, still lifes, and floral compositions, she constructs a visual language grounded in patience, devotion, and attentive observation. Each canvas becomes a space of reflection, where the ordinary is gently elevated into the realm of the poetic.

Tan’s paintings embody a sustained commitment to the values of harmony, balance, and painterly sincerity. Her compositions are measured, her color relationships carefully tuned, and her surfaces alive with subtle shifts of tone. In this way, her work participates in a lineage of artists who have approached painting not as a vehicle for spectacle, but as a means of contemplative inquiry. She demonstrates that technical refinement and emotional clarity are not relics of the past, but living possibilities within the present.

Within the broader context of contemporary art, her practice reminds viewers that the language of beauty and visual quietude retains its relevance. Her paintings offer a moment of stillness, a space in which perception can slow down and rediscover its sensitivity. It is precisely this capacity for calm reflection, this refusal of noise in favor of depth, that secures her place within the evolving narrative of contemporary painting. Her art does not announce itself loudly, yet it endures with quiet conviction, affirming the lasting power of the painted image.

By Marta Puig

Editor Contemporary Art Curator Magazine

Misty River 2018 acrylic 12" x 16" (?)

Vilagio 2010 Acrylic 18"x24"

Flower and Lace Acryl 18"x24" 2011

California Poppy Acryl 16"20 2012

Havest acrylic 11"x14" 2012

Japanese Bridge, avrylic 8"x8" 2012

Lily6n Pond 16"x20" acrylic 2012

Birds of Paradise, acrylic 14"x14" 2012

Lily Pond acrylic 12"x16" 2012