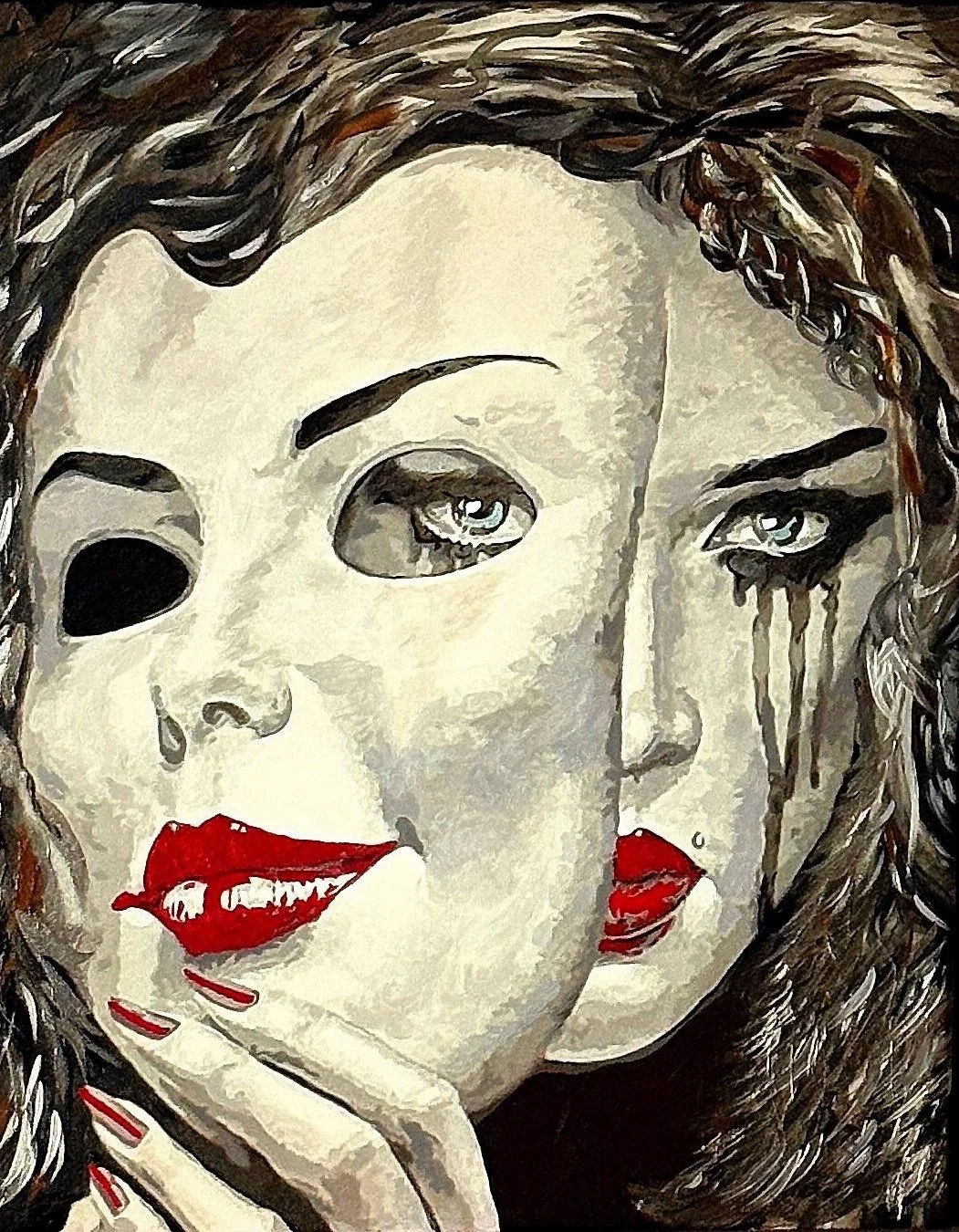

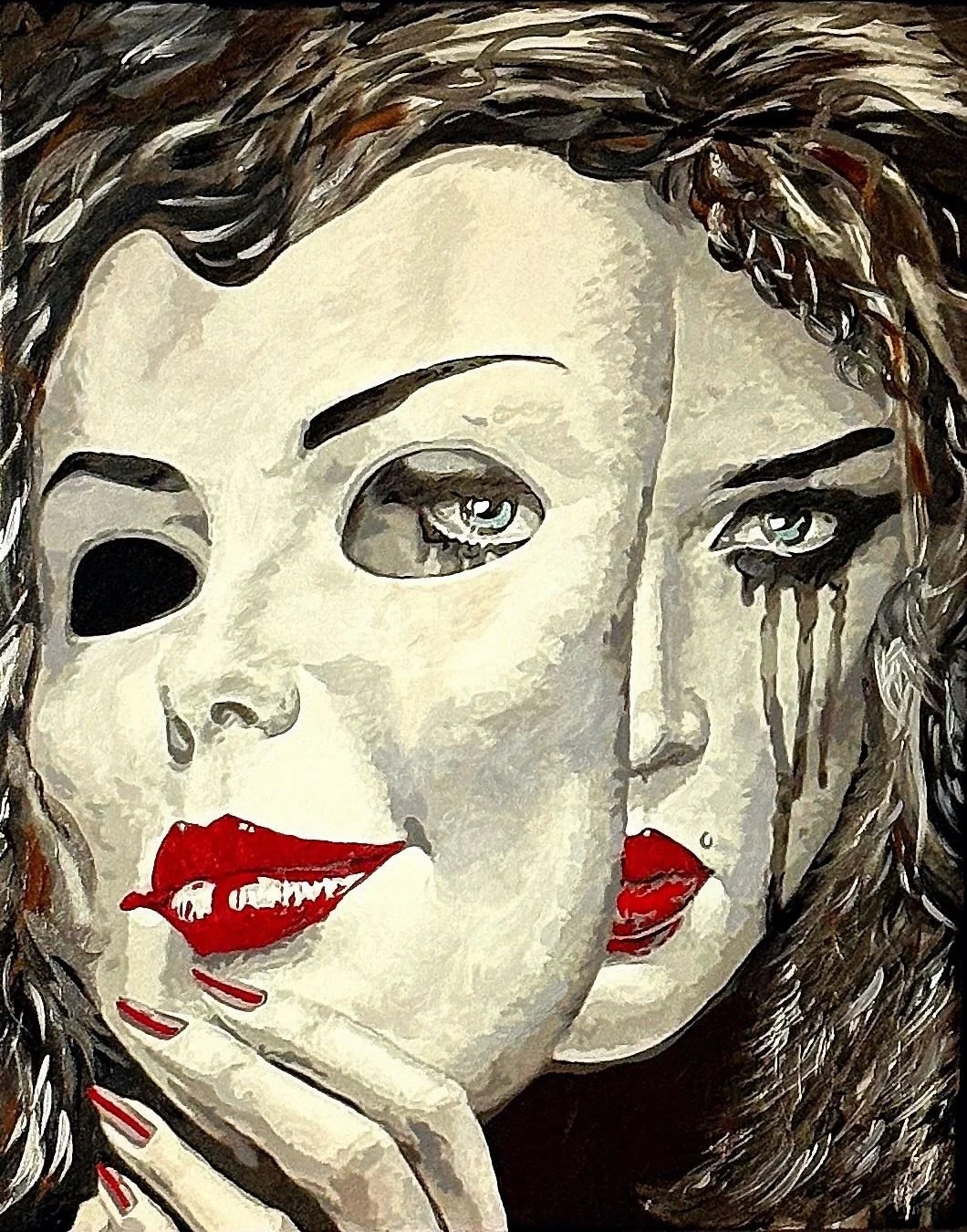

Interview with Alisa Chernova

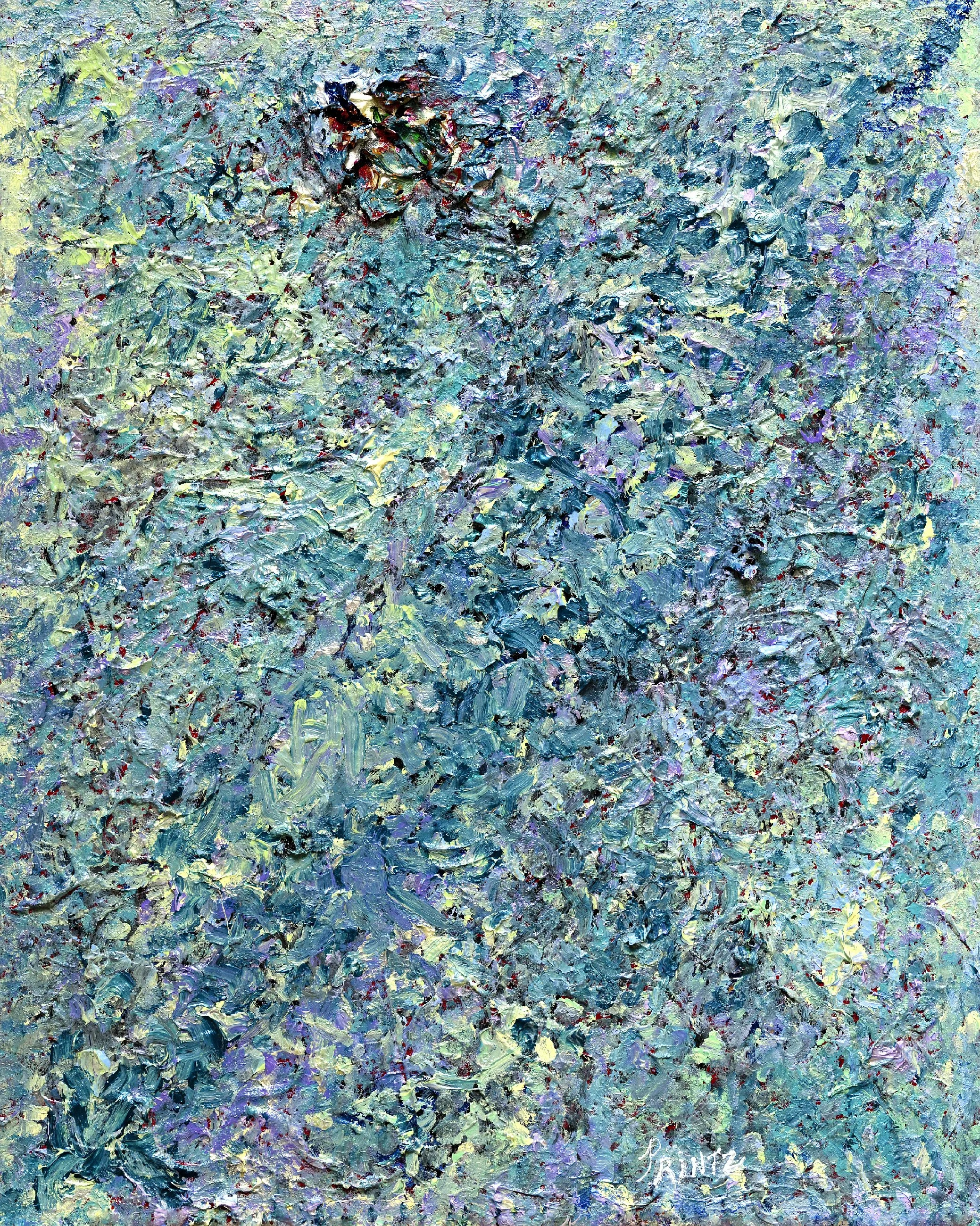

My art is a dialogue between psychology and painting — a space where inner conflicts, fears, and existential questions take visual form. Drawing on psychoanalysis and Gestalt therapy, I explore identity, time, and the fragile boundary between illusion and reality. Each work reflects an emotional experience — despair, anxiety, temptation, or the search for self — embodied through vivid contrasts of light, shadow, and symbolic imagery. My goal is to reveal what is usually hidden and to give voice to the invisible and unspoken aspects of human existence.

Your practice is shaped by a rare convergence of medical science, psychology, and painting, where observation, diagnosis, and intuition intersect. How does your training in medicine continue to inform the way you construct meaning on the canvas, and at what point does clinical knowledge dissolve into symbolic and intuitive decision-making?

My medical background taught me how to see beyond the surface. A physician observes, compares, doubts, and searches for causes rather than effects — and this approach has become an integral part of my painting practice. Each work begins with an attentive “examination” of an inner state or theme that has not yet found its form. At the same time, I seek balance: science brings clarity and integrity, while intuition introduces freedom and risk. Meaning emerges precisely at the moment when control softens and inner experience begins to speak on its own, opening space for new questions, evolving images, and future transformations.

You position art not simply as representation but as a form of dialogue, one that visualizes emotional states rather than illustrating them. How do you conceive of the painting as an interlocutor, and what responsibilities does that position place on the artist when engaging the viewer's inner life?

I perceive a painting as a living space for dialogue rather than a message with a fixed meaning. It does not explain or illustrate emotion; instead, it creates the conditions in which the viewer can encounter it. In this sense, the work becomes a conversational partner: it does not impose interpretation, but sets a tone, a pause, and an inner tension, leaving room for personal experience.

This position requires honesty in gesture and form, a refusal to manipulate the viewer’s emotions, and the willingness to leave meaning open. A painting must preserve inner freedom — for both the artist and the viewer — allowing the dialogue to continue and deepen over time.

Your conceptual project, In the Company of Sigmund Freud, engages directly with psychoanalytic thought while resisting literal translation. How do you transform Freud's ideas about fantasy, desire, and psychosomatic symptoms into visual structures that operate through suggestion rather than explanation?

In this project, it was important for me not to illustrate Freud’s ideas, but to enter into a quiet dialogue with them. I am interested not in theory as a system, but in a state — the moment when fantasy, desire, and bodily impulse have not yet taken shape in language, but are already felt.

I do not turn these ideas into clear symbols with fixed meanings. Instead, I translate inner tension through ruptures, shifts, layers, and pauses. The composition functions like a psychological process: without direct explanation, but with a sense of movement, resistance, and a hidden impulse. Here, form does not explain meaning — it allows it to emerge.

For me, it is essential that the viewer does not so much understand as feel — through the body, intuition, and personal memory. The painting becomes a space of suggestion: it does not offer answers, but creates the conditions in which the viewer encounters their own projections.

There is a persistent tension in your work between what is revealed and what remains unresolved, as if emotion appears not as a statement but as residue. How do silence, fragmentation, and ambiguity function as formal strategies within your compositions?

For me, it is essential to draw a clear distinction. I do not use painting as a therapeutic method, nor do I set the task of “healing” or correction for the viewer. A painting does not function as an instrument — it exists as an autonomous artistic statement, with its own logic, tension, and internal structure.

The psychological impact arises not because a therapeutic scenario is embedded in the work, but because contemporary art in general is capable of touching layers of experience that have not yet been shaped into language. I work with states rather than diagnoses; with vulnerable zones of perception rather than methodologies.

I do not guide the viewer, offer interpretations, or fix meaning. The painting remains an open space where each person may encounter their own self — or may not.

You describe art therapy as a tool for psychological correction and understanding, yet your paintings operate within the contemporary art field rather than the therapeutic setting. How do you maintain the autonomy of the artwork while allowing it to retain emotional and psychological potency?

I don’t transfer art therapy into painting as a method. Rather, it informs my sensitivity to psychological processes. My paintings are not tools for correction or healing — they remain autonomous artworks, operating within the field of contemporary art.

The emotional and psychological charge is preserved not through explanation or therapeutic intent, but through form, tension, and ambiguity. I consciously avoid direct symbols or diagnostic gestures. The work does not offer solutions or guide the viewer — it remains an open space where emotion can be encountered, but not interpreted on someone’s behalf.

Working from your studio in Spain, you continue to shape a personal visual language grounded in symbolism and introspection. How does the studio function for you as both a protected psychological space and a site of disciplined artistic labor?

My studio is a place where I feel calm and safe to work. Here I can be alone with my thoughts and sensations, without the noise of the outside world. It is a space where I allow myself to slow down, make mistakes, doubt, and gradually find the right inner state for painting.

At the same time, the studio is a place of discipline. I come here to work regularly, with respect for the process and for painting itself. Maintaining rhythm and focus is important to me, because it is through this consistency that clarity appears and my visual language takes shape.

In this way, the studio becomes a balance between inner freedom and professional focus. It is the place

In an era saturated with instantaneous imagery and rapid visual consumption, your paintings ask for sustained attention and internal reflection. How do you construct visual tempo and density to slow the viewer's encounter and encourage psychological engagement rather than immediate recognition?

I try to make my paintings so that they can’t be “grasped” in a second. There’s no single bright center that explains everything immediately. Instead, there are layers, pauses, and repetitions — the viewer’s eye needs to linger, move across the work, return, and notice details.

The density of the image alternates with emptiness, creating a rhythm and space for reflection. This slows down perception and allows the viewer to immerse themselves in the painting, to feel it rather than just recognize or “read” it in an instant.

This way, the viewer engages gradually, experiencing the process rather than a ready-made answer.

As your work circulates internationally through exhibitions, fairs, and digital platforms, it enters contexts far removed from the intimacy of the studio. How do you think about the transformation of meaning when a psychologically charged image moves into highly public and mediated spaces?

When a work leaves the studio, I don’t see it as losing its meaning. For me, meaning is not fixed — it shifts with context. The psychological tension from which the image emerges remains within the work, but in public space it begins to interact with the viewer’s own experience.

I don’t try to control interpretation. What matters to me is that the work preserves its inner energy and its ability to resonate — to provoke recognition, a question, or a subtle sense of discomfort. In this movement from the intimate to the public, I see not a loss, but an expansion: a personal experience becoming a point of encounter with others.

Your paintings have been described as mirrors that return the viewer to themselves, not through comfort but through confrontation. How do you imagine the role of contemporary painting today in addressing emotional complexity, vulnerability, and self-recognition without offering resolution?

For me, painting is not a way to provide answers or comfort. It’s more like a mirror that reflects the viewer’s state, showing inner layers, doubts, and contradictions. My aim is not to fix or resolve, but to allow these feelings to be noticed and felt.

Contemporary art, in my view, is especially valuable because it can reveal complexity and vulnerability without simplifying. A painting can hold the gaze, evoke a sense of vague unease, or, on the contrary, quiet focus. It opens space for self-discovery, allowing the viewer to encounter their own emotions and inner contradictions, without offering a ready-made solution.

In this way, the role of painting is not to solve, but to accompany the process of inner experience, creating conditions where a meeting with oneself becomes possible.