Interview with Sara McKenzie

Biography

My artistic evolution was highly influenced by my life’s layered geography. Born in Nebraska, and raised in both Southern California and Massachusetts, I developed an openness to contradiction: coast and prairie, order and improvisation. Life was shaped by curiosity and a hands-on relationship with a variety of media and materials: fabric, fiber, glass, paper, clay and paint, exploring visual relationships and emotional expression. Simultaneously, I trained and built a career grounded in science, data and design. I spent 40 years in the field of biotechnology, developing novel new drugs. Despite always identifying as a maker, I did not fully embrace the label “artist” until recently. Based in Santa Fe, NM, since 2014, and following study of landscape, figurative and abstract painting with local accomplished artists, I now devote myself to abstract painting. Since my first public exhibition in 2023, my career has expanded beyond borders, with my work appearing in exhibitions across the United States and Europe.

Artist Statement

My painting is less an act of depiction than one of discovery — an inquiry shaped by a life lived between scientific research and visual art. After four decades in biotechnology, where hypothesis, experimentation, and revision were daily practice, I came to understand that rigor and imagination are not opposites but partners. That understanding underpins my work.

In the studio, I approach the canvas as an experimental field. Composition, color relationships, material behavior, and structural tension form an internal grammar, learned deeply enough to allow improvisation. I layer pastels, acrylics, collage, and dimensional materials over extended periods of time, often removing as much as I add. Erasure is not correction; it is revelation. Each mark becomes information. Each disruption reshapes the inquiry.

Rather than working toward a predetermined image, I allow the conditions of the painting to evolve. Attention and sustained concentration operate as invisible materials, enabling subtle shifts to surface. The materials themselves — paint, paper, fiber, texture — act as collaborators, introducing resistance and possibility. What remains consistent is the method of engagement: iterative, responsive, and open.

Science values reproducibility; abstraction resists fixed outcomes. My methodology may be grounded, but each painting unfolds as an unrepeatable event — shaped by changing variables of perception, material, and time.

“Ancora Imparo” — I am still learning — reflects the ethos that guides my practice. Mastery, for me, is not arrival but sustained curiosity. Each painting is not a declaration of what I know, but a continuation of inquiry into what remains unknown.

Sara, in your transition from a four-decade career in biotechnology and drug development to an intensive commitment to abstract painting, how has the discipline of hypothesis formation, testing, and revision shaped the way you approach a canvas as an experimental field rather than a site of expression alone?

It may sound surprising, but after four decades in biotechnology, the studio feels like a laboratory — and also like a playground. The two are not opposites.

In science, I was trained to form hypotheses, design conditions, observe outcomes, and revise. That discipline profoundly shaped how I approach a canvas. Before I begin, I may carry a working proposition: what might happen if this form meets that openness, if this color field interrupts that structural rhythm. But like any experiment, the result is rarely identical to the initial hypothesis.

Having mastered certain techniques, I can rely on what I know will produce specific effects. But it’s the “what-ifs”, the variables introduced under new conditions, that generate discovery. Sometimes they yield an unexpected visual coherence. Sometimes they fail entirely. Both outcomes contain information.

Approaching the canvas as an experimental field rather than a site of expression frees me from attachment to a preconceived result. It allows revision, layering, subtraction, and restructuring — much like refining a scientific model. What remains constant is the inquiry.

Ultimately, the discipline of testing, revising, and retesting, has taught me something invaluable: uncertainty is not a threat to the work; it is the engine of it.

When you describe painting as discovery rather than depiction, it closely mirrors scientific inquiry, where outcomes are unknown at the outset. How do you cultivate trust in uncertainty and resist the impulse to control results learned through years of high-stakes research?

Interestingly, years of high-stakes research did not train me to control results. They trained me to release them.

In science, the rigor lies in designing a well-controlled experiment: defining variables, establishing parameters, ensuring clarity of method. But once the experiment begins, the outcome cannot be coerced. The data must be allowed to speak. The integrity of the process depends on openness to whatever emerges, even when it contradicts expectation.

That posture carried directly into my painting practice. I can structure a canvas with intention: choose materials, establish compositional tensions, introduce certain conditions. But once the process unfolds, something unanticipated always occurs. Rather than resisting that deviation, I’ve learned to trust it, and even to seek it.

Trust, for me, does not mean passivity. It means confidence that something will emerge. That a result is inevitable. The creative act lies in how I respond to what appears. Each mark becomes information. Each disruption becomes possibility. The next “what-if” arises from what the painting reveals.

Both science and art taught me the same discipline: control the conditions, not the outcome. That’s where discovery lies.

Having worked in a scientific environment where precision and accountability are essential, how did you learn to transfer that rigor into painting without allowing it to suppress intuition, play, and emotional risk?

That tension is actually the joy of the artistic process for me! After decades in environments where precision and accountability were externally measured and highly consequential, I discovered that rigor in painting operates differently. But it is no less real.

In science, precision is quantifiable, and accountability is collective. In painting, the precision is perceptual: the exact relationship between colors, the weight of a line, the balance of tension and space. But the accountability is internal. I am responsible for the coherence and integrity of the work.

What changed was not the presence of rigor, but its purpose. In the studio, rigor becomes the scaffolding rather than the constraint. It allows intuition to move more freely because the structure can hold it. The discipline of observation I cultivated in science, noticing subtle shifts, evaluating outcomes carefully, now serves the painting rather than suppressing it.

Play and emotional risk are not the opposite of rigor. They require it. The more attentive and disciplined I am, the more space there is for intuition to take meaningful risks. In that way, my scientific training didn’t diminish the artistic process. It gave it backbone.

Your process of layering, adding, and removing material recalls iterative experimentation in the lab, where negative results are as informative as positive ones. How do acts of erasure, failure, or reversal function as knowledge within your paintings?

In both the laboratory and the studio, removal is not subtraction — it is revelation.

When I erase, scrape back, or reverse a decision in a painting, I expose relationships that were previously concealed. New structural tensions appear. Unexpected color harmonies surface. What initially seemed like a misstep becomes information.

In scientific research, so-called negative results refine the model. They narrow the field of possibility and clarify what is actually happening. The same is true in my paintings. A layer that does not produce the anticipated effect does not represent failure; it reshapes the inquiry. It alters the parameters of the next move.

Erasure is therefore an active form of knowing. It interrupts assumption. It destabilizes certainty. It asks the work to reconfigure itself.

When I say the painting “tells me” what it needs, what I mean is that the accumulated marks, the visible history of decisions, create a set of conditions. My role is to observe those conditions carefully and respond. Each act of removal becomes a conversation with what is already there.

There is no absolute failure in this process. Only data, revision, and the next layer of discovery.

Many people imagine science as procedural and art as intuitive, yet your practice suggests creativity is central to both. How has your scientific career sharpened your capacity for imaginative leaps rather than limiting them?

Science is far more intuitive than people generally assume. Many transformative discoveries began not with procedure, but with perception. When Alexander Fleming noticed that mold had contaminated his petri dish, he could have discarded it as a failed experiment. Instead, he observed something unexpected: the bacteria would not grow near the mold. Rather than asking how the contamination occurred, he asked why the bacteria were dying. That shift, from error to mechanism, was an imaginative leap grounded in disciplined observation.

My scientific career sharpened that same reflex in me. Years of designing experiments and analyzing results trained me to look closely at anomalies rather than dismiss them. Unexpected outcomes are not interruptions; they are invitations.

In the studio, this translates directly. If a layer behaves differently than intended, I don’t discard the painting. I study it. I ask what new relationship has emerged; what structural possibility has revealed itself. The discipline of sustained experimentation, learning how materials respond, how marks interact, how surfaces hold tension, becomes the foundation that allows intuition to operate with confidence.

Imaginative leaps are not spontaneous flashes detached from rigor. They arise from deep familiarity with a system. Science taught me to know a system well enough to recognize when it is pointing somewhere new.

You often allow each layer to inform the next without a preconceived image in mind, similar to how data redirects an experiment midstream. How do you recognize when a painting is asking for a change in direction?

There’s a well-known idea, often attributed to Picasso, that one must learn the rules deeply before being able to break them meaningfully. Over decades of working with composition, color relationships, spatial dynamics, material interaction, and mark-making, those principles have become less like rules and more like an internal grammar.

Because that visual language is embodied in me, I can sense when something is unresolved. It may be a subtle imbalance of contrast, a tension that feels static rather than dynamic, or a color relationship that dulls instead of activates. The recognition is often intuitive at first, a feeling that the painting has stalled, and then analytical awareness follows.

That’s when direction shifts.

The analytical mind doesn’t override the painting; it offers possibilities. Perhaps a rule needs to be reinforced. Perhaps it needs to be disrupted. Perhaps a new material introduces the necessary friction. The accumulated knowledge and experience of years in both science and art gives me options.

So when a painting “asks” for change, what I’m really responding to is the internal logic that has emerged on the canvas. Experience allows me to hear that signal and to trust it enough to pivot.

In scientific research, collaboration between tools, systems, and human judgment is essential. How does this sensibility inform your relationship with materials, allowing paint, paper, and texture to act as collaborators rather than instruments?

In scientific research, tools are never passive. Instruments, systems, and human judgment form a feedback loop, where each shapes the direction of inquiry. You don’t impose meaning on the data; you learn how to listen to what the system is revealing.

I relate to materials in my studio in much the same way. Paint, paper, fiber, and texture are not neutral instruments executing my intent. Each material has its own behavior, resistance, and possibilities. How pigment spreads, how paper absorbs, how surfaces interact, these responses actively inform what comes next.

My role is not to control the materials, but to set conditions and then pay close attention. A material may push back, behave unexpectedly, or suggest a direction I hadn’t anticipated. That response is information. It shapes the next decision; just as experimental data redirects a line of scientific inquiry.

Over time, my work with various media has become a form of collaboration. Human judgment provides structure and intention; materials contribute unpredictability and discovery. The painting emerges from that exchange rather than from a fixed plan.

In both science and art, meaning arises not from dominance, but from dialogue: between intention and response, question and evidence, hand and material.

Your paintings often unfold over long periods of time, much like extended research projects. How does duration alter your understanding of resolution, and when do you sense that an artwork has reached a meaningful conclusion?

The duration of creating a painting is not something I predetermine. Some works resolve within a week. Others remain in conversation with me for a year or more. Much like extended research projects, the timeline is dictated by the evolving conditions of the work itself.

There are moments when the next step is clear and a layer suggests its successor. But there are also times when nothing feels evident. Earlier in my practice, I sometimes interpreted that pause as failure. Experience has taught me otherwise. When the next move is not apparent, it usually means the painting is still reorganizing internally, and so am I.

In those periods, I set the work aside but keep it visible. The distance allows perception to recalibrate. What initially felt like blockage becomes incubation. Over time, a new structural possibility, color relationship, or formal intervention emerges with clarity.

Duration also alters my understanding of resolution. A painting does not conclude because it has exhausted options; it concludes because it has reached equilibrium. The internal tensions feel resolved, the relationships hold, and there is nothing more to test without diminishing the coherence that has formed.

A teacher once described it simply: a painting is finished when it stops talking to you. For me, that means it no longer asks a question. It stands on its own logic. And I’ve learned to recognize that quiet.

The phrase Ancora Imparo embedded in your signature suggests perpetual learning, a principle shared by both science and art. How does this ethos shape your refusal of mastery in favor of ongoing inquiry?

“Ancora Imparo” — I am still learning — is less a motto and more a position from which I work.

Over decades in both science and art, I’ve come to understand that knowledge expands the horizon of what remains unknown. The deeper one goes, the more complexity reveals itself. That recognition fosters humility rather than certainty. It keeps curiosity alive.

For me, refusing mastery does not mean rejecting skill or experience. It means resisting the illusion of arrival. Technical fluency can easily harden into formula. In both scientific research and painting, the moment one assumes the answers are known, inquiry narrows.

The ethos of ongoing learning protects against that narrowing. It keeps the work porous. It invites experimentation, risk, and revision. Each painting becomes less a demonstration of what I already know and more a site of investigation.

“Ancora Imparo” is a reminder that evolution is the practice. Mastery, if it exists at all, lies not in conclusion but in sustained openness.

Your life between different geographies and disciplines has cultivated an openness to contradiction. How do these tensions, order and improvisation, analysis and intuition, become structural forces within your compositions?

I’m not sure those tensions function as structural forces within the composition as much as they shape the way I move through it.

Living between geographies and disciplines has made me comfortable inhabiting opposites, order and improvisation, analysis and intuition, without needing to resolve them prematurely. That comfort translates into the studio. Years of studying composition, color dynamics, spatial relationships, and material behavior have helped me to internalize a visual grammar of sorts. Because that grammar is embodied, I can enter a state of improvisation without losing overall coherence.

At the same time, there are moments when I deliberately shift modes. I step back from immersion and assess the work with a more analytical eye, not to suppress intuition, but to recalibrate it. I consider contrast, balance, tension, and rhythm. Then I return to the flow of making.

That oscillation becomes a kind of structural rhythm. The compositions often hold dynamic tension — areas of restraint alongside areas of disruption, clarity beside ambiguity. I think that reflects the way I’ve learned to inhabit contradiction: not as conflict, but as generative balance.

Practice makes that movement fluid. Over time, analysis and improvisation stop feeling like opposing forces and begin to operate as a single, responsive system.

Science values reproducibility, while abstraction resists repetition. How do you reconcile methodological consistency with the need for each painting to remain an unrepeatable event?

Abstraction resists depiction more than it resists repetition; it resists fixed outcomes. That distinction matters.

In science, reproducibility validates a finding. A result must be obtainable under the same conditions to be trusted. The scientific method is designed to produce consistency across individual scientists and across trials.

In my painting practice, the methodology may remain consistent: I draw from the same foundational knowledge of composition, material behavior, and structural dynamics. But the conditions are never identical. The moment, the state of attention, the subtle interaction between materials, even the accumulated history of prior marks, all shift the terrain.

Even when I attempt to revisit an earlier visual language, the result invariably diverges. Not because of lack of control, but because the variables are alive. My perception evolves. The materials respond differently. The context changes.

What remains reproducible is the inquiry, the disciplined engagement, the iterative layering, the attentiveness to emerging relationships. What remains irreproducible is the event itself.

In that sense, each painting becomes analogous to a single experiment conducted under dynamic conditions: methodically grounded, yet unrepeatable in its precise unfolding.

After decades of making privately, what shifted when your work entered public exhibition, and did presenting your paintings alter your sense of responsibility toward the viewer as a participant in the experiment?

My shift into public exhibition did not come from external pressure; it came from an internal clarity. At a certain point, I knew I was ready to name myself as an artist and to let the work stand in a shared space.

Exhibiting did not fundamentally alter my relationship to the paintings themselves. I remain most invested in the process of making: the inquiry, the risk, the resolution. When a painting is complete, I often feel a sense of release rather than attachment. The work has done what it needed to do for me.

What has changed, perhaps, is not responsibility but awareness. Once the work enters public space, it becomes part of another person’s perceptual field. I don’t feel obligated to guide or control that experience. My responsibility is to the integrity of the work, to ensure that it is fully realized, structurally sound, and honest to its own internal logic.

After that, the painting is no longer solely mine.

I take genuine pleasure when viewers pause, reflect, or feel something in response. Not because their reaction validates the work, but because it confirms that the painting continues the experiment beyond me. The viewer becomes another variable in the inquiry, bringing their own history, perception, and interpretation.

If I hope for anything, it is not agreement or understanding, but engagement. A reaction, of any kind, means the work is alive in the world.

Your studio environment is carefully structured to protect focus, similar to a controlled experimental setting. How do attention and concentration operate as invisible but essential materials in your work?

My studio environment is structured with intention. Music in the background, no competing demands, no fragmentation of attention. These conditions create a container for sustained focus.

Attention for me is not passive. Just as a controlled laboratory setting reduces noise in order to perceive subtle data, a protected studio environment allows me to detect small shifts in tone, balance, texture, and spatial tension. Without that concentration, those signals would be missed.

When I enter a state of deep immersion, analysis quiets but awareness sharpens. I am not abandoning discernment; I am refining it. In that space, intuition becomes more perceptible. I can sense when a color relationship activates or deadens the surface, when a mark destabilizes or strengthens the composition.

When I say I “hear” what the painting wants, I mean that sustained attention reveals the internal logic already forming on the canvas. My role becomes responsive rather than directive.

Concentration, then, is not simply a mental state — it is a structural force. It is the invisible condition that allows the work to evolve with coherence and depth.

You often describe your paintings as mapping inner or subconscious experience. How does this act of visualizing the invisible parallel scientific efforts to model phenomena that cannot be directly seen?

I think of emotional states, memory, and consciousness as real forces, even though they are not directly observable. In my paintings, color, form, texture, and spatial relationships become analogues for shifting energies: psychological tension, expansion and contraction, the subtle architecture of inner experience. In that sense, painting is a form of modeling.

Science builds models to make invisible phenomena intelligible: gravity curving space, quantum probability fields, neural networks firing in the brain. These models are not the phenomena themselves. Rather they are structured attempts to understand forces we cannot see directly. And they evolve as new data emerges.

My canvases function similarly. Each one is an investigation, a visual experiment that tests how inner experience might become form. The process is iterative, provisional, and humbling. Like science, it requires curiosity, disciplined intuition, and a willingness to revisit what I think I know.

Both practices, ultimately, are acts of translation. They seek to render the unseen understandable.

As someone who has lived fully inside both scientific and artistic cultures, what assumptions about creativity do you most hope your work quietly unsettles by demonstrating that invention, rigor, and imagination belong equally to both?

Having lived fully inside both scientific and artistic cultures, I’ve become sensitive to the myths we carry about each field. Science is imagined as rigorous but unimaginative, art as imaginative but undisciplined. I hope my work unsettles that division.

To move between these worlds is to see how similar they actually are. Both begin in curiosity. Both require long apprenticeship. Both depend on structure as much as intuition. A scientific theory is an act of imaginative architecture: disciplined speculation about how unseen forces behave. A painting is no less rigorous: it tests relationships, balances tensions, refines variables, and evolves through revision.

As a lifelong learner, I’ve never felt at home in silos. I’m drawn to the edges where languages overlap, where a diagram begins to feel poetic, or a canvas begins to function like a model. Working across disciplines has taught me that invention is not owned by art, nor is rigor the property of science. They are shared habits of attention.

If anything, my practice demonstrates that imagination deepens under constraint, and rigor becomes more alive when infused with wonder. The scientist and the artist are not opposites. They are parallel expressions of the same human impulse: to understand, to test, to refine, and to keep learning.

At Work In Studio

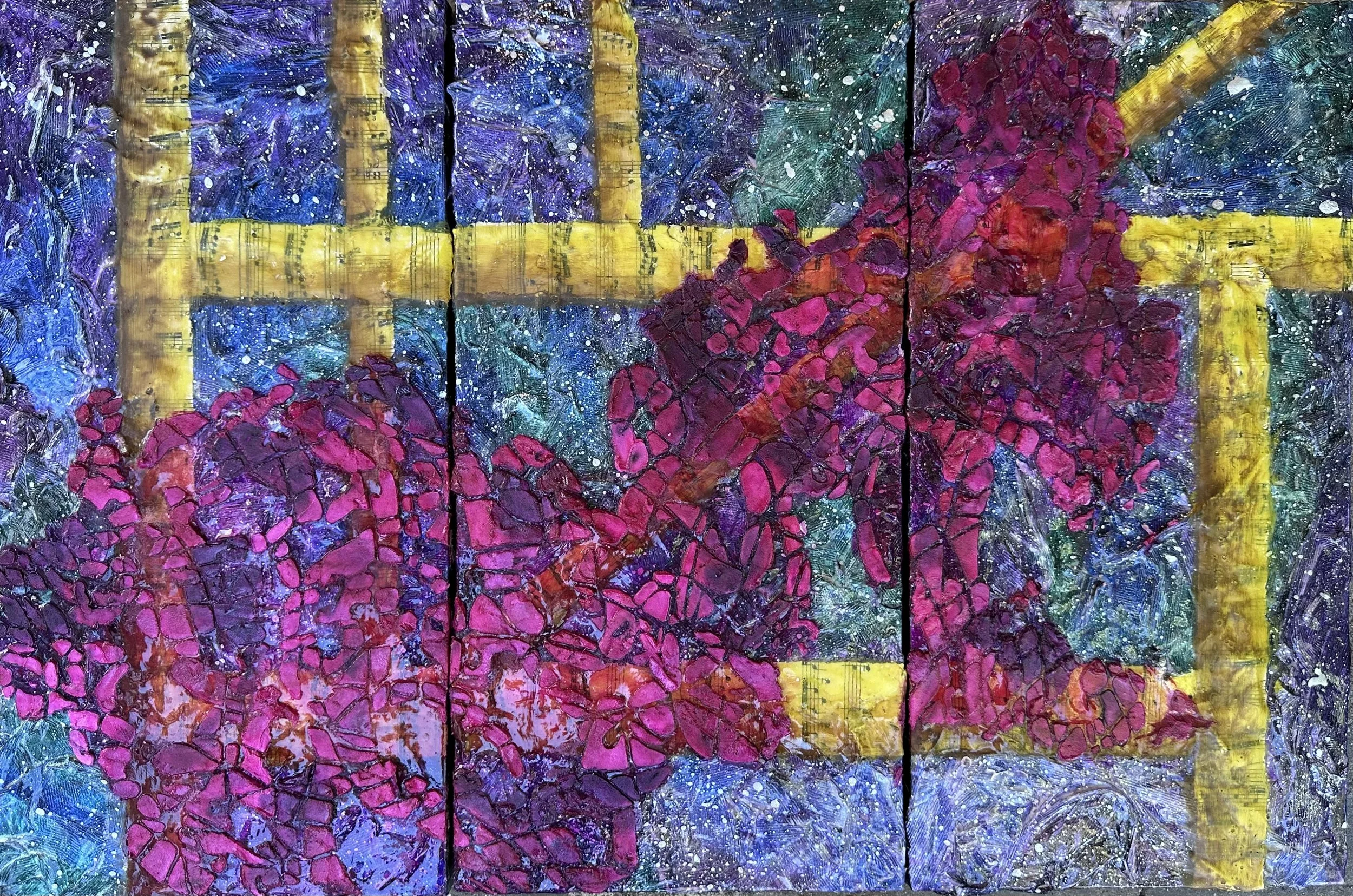

Blossoms In Song

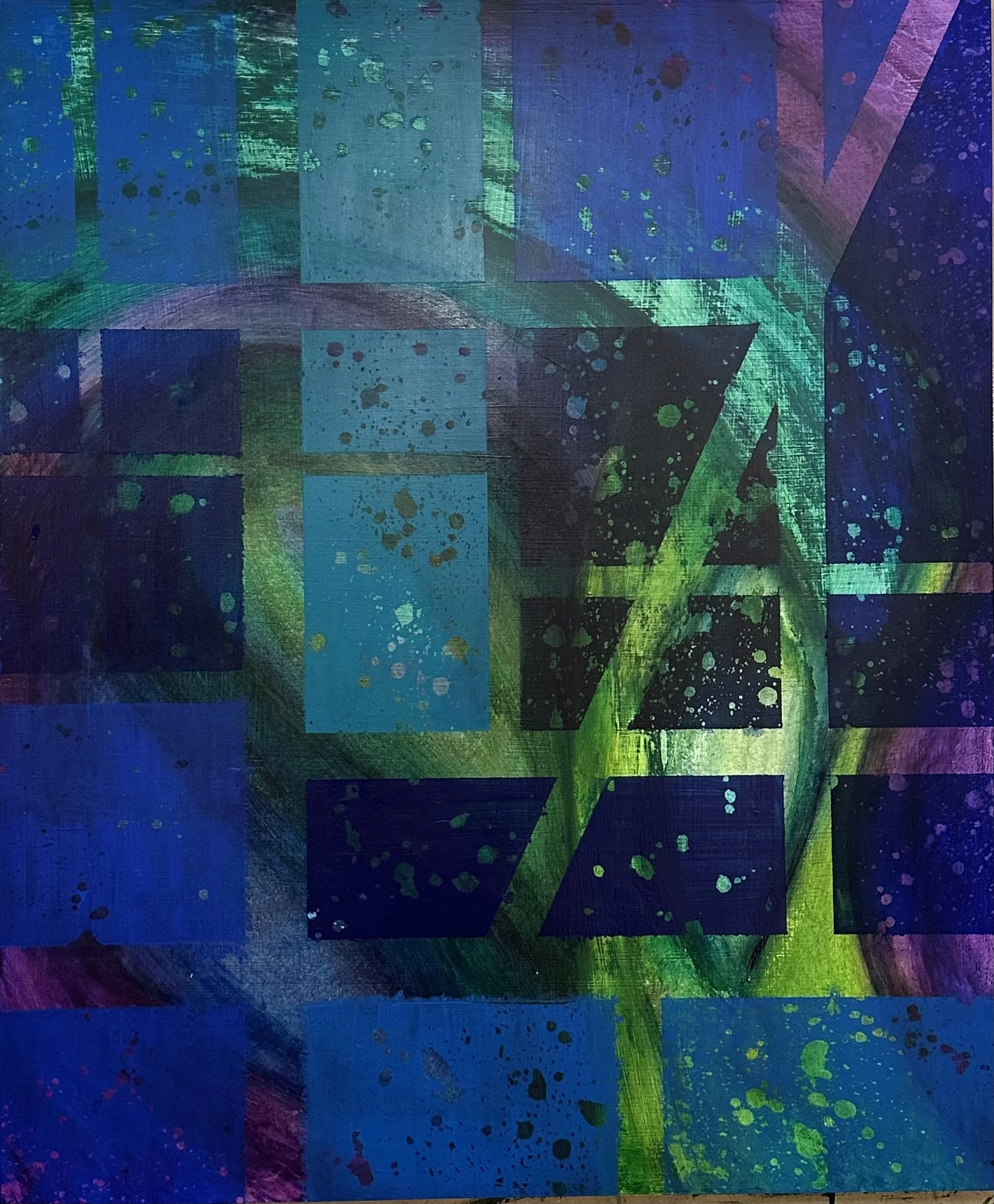

Boldly Go

Counterpoint

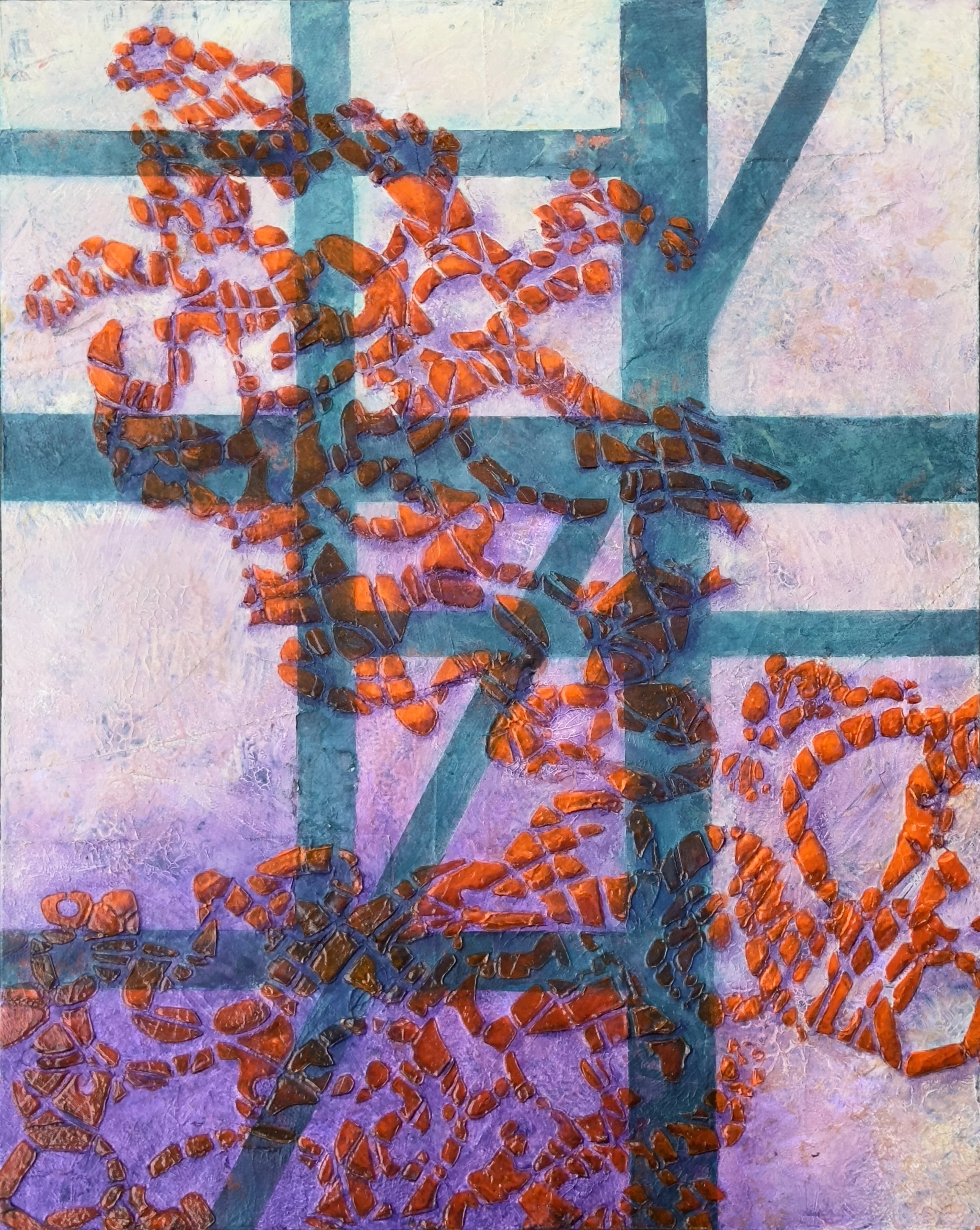

Crimson Travels

Entangled Spirit

Fresh Powder

Garden Path

Interwoven

Progression In Retrograde

Pura VidaI

Tapestry Of Harmony

Through And Over

Tickeld Pink

What Lies Beneath