Interview with Harry T. Burleigh

https://www.artfulkryptonite.com/

As a child, Harry Burleigh grew up as the youngest of three in Clarksburg, West Virginia. He had two sisters. One was two years older, and the other was five years older. His artistic expression began when he was just a toddler. When his mother wanted to know who had scribbled all over the wall with red Crayons, he pointed to his sisters. His mother knew that it was Harry because the markings only went as high as he could reach. She let him live.

A few years later, he became fascinated with science fiction films. Often, he and his father would stay up late on Saturday nights watching horror movies and ghost stories, waiting for the monsters and ghouls to be revealed.

Many coloring books later, in the late 60’s, Harry had his first true inspiration to make art. His mother brought home a record album with a beautiful woman on the cover holding a guitar. He was so taken with the image on the cover that he felt compelled to do something about it. He tried to recreate it with a pencil and even attempted to trace it but failed miserably. This left an indelible impression on his mind that would resurface later in life.

He entered his first art class when he was a junior in high school, where his teacher realized that he had potential and tried to inspire his progress. He didn’t produce many pieces of art, but he began to realize that he had the talent to do so if he applied himself. During this time in his life, he was constantly annoyed by catching glimpses of faces and odd shapes in woodwork, floor tiles, and just about everywhere there was an unnatural pattern. He found himself sketching surreal images in the margins of his notebooks when his attention wandered in chemistry class. Whenever the annoying faces showed up in his own sketches, he just gave in and included them. Later in life, he discovered that he was not cursed with seeing these shapes and faces everywhere, but instead, he had been truly gifted with pareidolia, which is the ability to identify significant patterns and images in random and often accidental arrangements of lines and shapes. He was actually seeing three-dimensional images, seemingly within two-dimensional surfaces.

When his parents offered to pay for college, he assumed that going into fine arts would be easy and had never considered the cost of books and materials, that is, until he was required to have them.

During his college years, he detested core classes and only concentrated on his studio artwork. While this was a mistake academically, he was well aware that he did not fit the mold of a model student. At that time, he struggled with time management skills, pulling numerous all-nighters to meet the deadlines for his studio classes. He once totaled two cars after staying up all night and trying to get to his critique on time. Once, during the winter months, he was running down the stairwell from his classroom, sprained his ankle, and spent the next three weeks on crutches wearing a cast.

For extra credit in one of his core classes, he reluctantly had to dress as a servant at a medieval banquet and serve water for the elite. For the same class, he was given an option by the dean to do artwork for extra credit. He brought the work to the dean’s office, who seemed genuinely impressed by his talent. The art project was not quite finished, so he explained that when it was completed, the dean could keep it. Later, he found that he had been given no additional credit, so he kept those works for himself and still has them in his studio.

Harry designed T-shirts for different sections of the West Virginia University marching band, the university's fraternities, and for his friends. In most instances, he did not charge them any money for his work.

He did not graduate from college after four years. He was on the five-year program. He wasn't even sure that he would be graduating at all. When he finally did, he spent an entire summer without work. This tended to make my jaw rather tight because he didn't relish the thought of borrowing money from his parents.

Finally, he had two separate offers from TV stations in West Virginia to work as a graphic designer. After doing layouts for furniture advertisements and TV Guide promotions, he was sick of producing this boring style of work for other people and resigned. He spent the next eight years working in video production for a biomedical facility. Everything from ambulance chasing to open heart surgery.

In an attempt to get into the motion picture industry, he donated plasma for extra money and used his vacation time to learn how to operate Steadicam equipment in Rockport, Maine. Simultaneously, he freelanced, operating film and video equipment for the WVU athletic department.

Later, he was hired as a video programmer in the entertainment department of a cruise ship company in Puerto Rico. He soon realized that this was not paradise and spent the next nine months seeking work in New York and Los Angeles, which contributed minimally to any type of artistic advancement. Short on funds, he was forced to move back to West Virginia, where he spent the next few months, associate producing for a PBS station while tending to his bruised, egotistical wounds.

A friend of his had been attempting to help him land a summer relief job working with a major network in Washington, DC. She was a director of photography and worked with all of the big shots. Due to a change in the station's politics, that opportunity fell through, and he ended up working for another college video department at the University of Maryland.

In brief, Harry Burleigh spent more than two decades producing no fine art whatsoever. He made one or two graphite sketches in his spare time to blow off steam, but they were never seen publicly. While he did design and construct several studio sets for television, he felt that it only helped him realize what he didn't want to do for a living.

By chance, he ended up in a phone conversation with an artist, who said that they once studied fine art at the same university but graduated prior to Harry's enrollment. Harry mentioned that he would be interested in seeing some of their artwork. In return, they mentioned that they might like to see some of his. At that time, Harry didn't even own a digital camera or a scanner, but he looked back at some of his earlier work and realized that he really wasn't all that bad. At this point, however, he felt that he had strayed so far from his artistic past that attempting to revive it could only result in failure and disappointment.

In 2004, His wife gave him a spectacular easel for his birthday and had been encouraging him to get back into art. In 2005, they bought a house in Virginia, where he began painting in earnest. He felt a need to jettison those things from his formal training that he felt were too restrictive. It was at this point that he also decided to put the monsters back in the closet and concentrate on resurrecting the beauty that he remembered from his mother's album cover. Working with oil-on-canvas, he began focusing on several techniques utilizing various colors and gently curved lines. This would develop into a series of figurative abstracts with a touch of fantasy and surrealism surfacing randomly in his work.

In 2006, he entered his first public competition in SoHo, Manhattan. The night before he was to transport his work to New York, he nearly cut the end of his finger off with a utility knife and had to tend to his injury throughout the entire exhibition. He received a Grand Jury Award for Theosophical Surrealism from the New York International Art Festival. There, he exhibited twenty-two paintings of oil on canvas. Since that time he has received numerous awards for his digital, non-representational work from the American Art Awards, in 2016, multiple awards for Special Recognition from the Light Space Time Gallery’s 2nd Primary Colors Art Exhibition, in 2020, multiple Certificates of Artistic Excellence from the J. Mane Gallery H20, in 2021, the Vision Contemporary Art Curator Magazine, Collectors International Award, in 2021, and the Collector’s Legacy Impact Award, Art Tour International, 2025.

Harry is also an author, having penned “A Muse Meant for You: Burleigh’s Rules of Creative Engagement for Aspiring Painters,” published by Artful Kryptonite in 2025, and currently available on Amazon.com.

Burleigh has amassed numerous accolades, but respects his own theory that people will say, do, wear, and drive just about anything, so there's a sustained possibility that any artist can eventually develop a following. He produces the work to meet his own expectations, and if others find that they like it, it is all the best. His artwork has been displayed in London, Italy, Monaco, and for a prominent airline. He is currently represented by a prestigious gallery in Chelsea, New York City. In 2025, Harry was selected for inclusion in Marquis Who's Who as a Top Professional, having achieved career longevity and demonstrated unwavering excellence in the chosen field of fine art. In 2026, his image will be presented by Marquis Who’s Who on a Jumbotron in Times Square. Harry’s work will also appear in hardcover editions of Art Celebrity and Top Investable Artists 2026.

Harry, your process foregrounds emergence rather than premeditation, allowing images to announce themselves only after repeated acts of looking, rotation, and return. How do you understand this oscillation between intention and recognition as a model of authorship? Does the painting decide its own ontology over time, or do you see authorship as a sustained negotiation between intuition, discipline, and perceptual training?

When I allow initial paint strokes to show themselves until an idea emerges, it's not an oscillation between intention and recognition. It's just a starting framework for a painting. Several options may present themselves before I choose one, due to what I believe possesses personal integrity, and what I truly think might look totally ridiculous. Just because I wait for something to strike me visually doesn't mean that it doesn't have to have my approval of what I will accept to work with. Ultimately, what goes down on the painting comes from my hands, my decisions, and my final approval. Finding an inspirational area within the initial strokes of pigment to start painting is simply that... a starting point. Metaphysics can only travel so far in my studio.

Much like with formal training, someone has to ultimately know the backbone of an artwork's structures. In a world outside of artificial intelligence, someone ultimately has to do the work. Paintings quite simply don't paint themselves.

You have spoken about resisting the notion that all visual forms have already been exhausted by history. In what ways does your engagement with abstraction and surrealism function less as a stylistic inheritance and more as a critical position, one that tests whether originality today can be rethought not as novelty, but as a reconfiguration of how meaning emerges from ambiguity?

Resisting the notion that all creations have been made before is more of a mental exercise to enhance inspiration to creatively achieve, rather than and arms folded surrender to one's lack of originality. There should be no doubt that many of the ideas that I originally thought were first-time possibilities turned out to have been created in the past. New artistic styles rarely appear from nowhere—they evolve by modifying, reacting to, or blending inherited traits. Add to that an artist's individual style, and you move more into a position of criticality.

An artist, not attempting to emulate other artists, will unquestionably develop their own stylistic fingerprint. I see stylistic inheritance as more of a basic framework. I still have to bring my own tools and thoughts to the table. Meaning often emerges from ambiguity for me, depending on what I am observing. How others end up receiving abstraction and surrealism is a matter of complete individuality.

The moment at which you decide a work is finished appears to be neither purely formal nor strictly emotional, but something closer to an internal calibration. How do you theorize completion within a practice that resists planning? Does finished signify resolution, saturation, or a deliberate refusal to further intervene?

In a practice that resists planning, one still has to have an eye for color, balance, and composition. This comes more naturally for someone who has been delving into the art world for many years. Knowing when a composition is too crowded is key, and while less is more works to a certain extent, one swipe of paint on an empty canvas seldom does a completed masterpiece make. Upon starting a painting, there is nothing on the canvas, so there is nothing to resolve and nothing to be frightened by. We create our own pressure, often without need. Concerning completing a piece of work, a refusal to further intervene is like giving up. Not an option. Finished, for me, is exemplified by knowing that a work of art meets my own personal standards. This doesn't happen overnight.

Your use of rotation during the painting process destabilizes fixed orientation and challenges the authority of a single correct viewpoint. How does this physical act of reorienting the canvas inform your thinking about perception, particularly in relation to the viewer’s encounter with the work as a site of interpretive instability rather than visual certainty?

I am truly not bothered when it comes to challenging the authority of a single correct viewpoint. I'm a rule breaker. If every artist caged themselves with rules, everyone's art would be more predictable, minus their own personal style. Broken rules are what feed the expansion of art, though many purists refuse to admit it. If a new animal species were to be discovered and you caged them in a zoo and put a camera on their head, you might learn fifteen things about this new addition to the animal kingdom.

If you put that same camera on their head and let them live in the wild, you could very easily learn volumes. I rotate paintings as I work on them, which really isn't all that uncommon, because other images of merit may appear. Ones that might require a little more attention. Also, observing the work from various distances is equally important. As for the viewer, they have no idea what angles I was using in order to orient a canvas. If they are not comfortable with what they are seeing, it's much like watching television. If you don't like what you are seeing, change the channel. There are thousands of other fantastic artists out there with whom they may better connect.

Color enters your practice not simply as a technical expansion but as a philosophical shift away from darkness toward affirmation. How do you understand color as an ethical or affective agent within the work? Does it operate as a mood, a structure, a symbol, or as something more resistant to linguistic capture?

Color plays an important role as I am producing the current style of imagery that I am focusing on. My shift away from darkness is not necessarily permanent. At some point, I may change directions and work on a darker series, but in the meantime, I will work more with warmer, or at least more visually pleasing imagery. I also believe that if darker imagery can sometimes come across as visually pleasing and, at times, very beautiful. Color has a very psychological effect on our senses. This is a scientific fact. How one chooses to go about using it can be quite obvious, or in some stealthier cases, far more diabolical. My use of color is directed more for overall mood and sometimes symbolism. It is not necessarily intended for linguistic capture.

You have described a conscious movement away from imagery that felt personally corrosive toward visual languages that cultivate positivity. How do you negotiate the tension between personal well-being and artistic rigor, particularly within a contemporary art discourse that often equates seriousness with discomfort or psychological intensity?

Having moved away from imagery that is more disturbing is not necessarily a permanent move for me. It's where I am currently in my particular sojourn. When the time comes, who knows? I may opt for a complete study in morbidity. I grew up loving science fiction, horror, and comedy films. None of which I have fully incorporated into my current work. Contemporary art discourse is a period, a fad, if you will, that will eventually change over time. I'm not here to please the market with my work. I am here to produce the work that works for me, and that I don't mind showing publicly. It's also a comfort knowing that I have already made it past some prominent gallery gatekeepers internationally.

Titles play a decisive role in your practice, functioning less as explanatory labels than as thresholds of recognition. How do you conceive of the title as an extension of the work itself? Does it anchor meaning, provoke misreading, or act as a subtle apparatus that guides the viewer’s subconscious rather than their rational interpretation?

If an artist is attempting to market their art, the title of a painting, or any work of art, is imperative. I've written an entire section about it in a book that I published in 2025 titled "A Muse Meant For You!" There is no excuse for not titling your work if your intention is to sell. Oddly, some of the culprits who do not are very good artists. In many cases, they have already made a name for themselves. UNTITLED. That's the first way to tell a viewer that, yes, you produced the painting, but in all the hours that you spent working on it, you did not gather enough of a feeling about what it might be called. This is how you make people feel less intrigued about your work. When viewers look at a work of art, they want to know more about the piece. Without a good title, you are shooting yourself in the foot.

This is an artist's opportunity to really reach out and pull them in with a good title. Even if they don't understand your title, it will build their interest. For those who truly prefer the novelty of not having a title, there are several art festivals that are specifically designed to support and market untitled work.

Your skepticism toward academic authority during your formal training suggests an early resistance to institutional validation. Looking back, how do you situate that resistance now? Do you understand it as a necessary condition for creative autonomy, or as a productive friction that sharpened your awareness of how artistic value is constructed and policed?

During my formal training, my skepticism toward academic authority did not encompass the entire artistic faculty. In fact, some of my instructors offered great teachings with regard to materials, techniques, and visual foundations. Others, however, were more focused on how much harder it was for them to graduate than it would be for our classes, or demonstrated that if we didn't solve visual problems in the ways that they would have, that it was to their disappointment and it was indicative of low-brow artistic merit. My aim was never to have my work emulate the style of my instructor's. I found the condition of creative autonomy to be only necessary in some areas of my formal artistic education. It did sharpen my awareness to better read people's intentions.

The prophetic dimension you attribute to an early surrealist drawing introduces questions of temporality and foresight within your work. How do you interpret this experience today? Do you see it less as a prediction and more as a manifestation of latent psychological or symbolic structures that only become legible retroactively?

The seeming prophetic dimensions in my work over time have had to take a back seat to coincidence, even though they were the inspiration for a change in my artistic direction. After this happens quite a few times, one starts to realize that no matter what you come up with, similarities will eventually pop up that might make you scratch your head and wonder. Hmm. I can be assured at this point, however, if I produced a painting of a winning lottery ticket, that I would very soon become none the wealthier.

Your workspace, shared with rescue animals, music, and controlled lighting, functions almost as a private ecology. To what extent do you consider the environment as an active collaborator in your practice, shaping not only productivity but the tonal and emotional registers that surface within the paintings?

My workspace environment is highly important. It's an area where something can be made from figuratively nothing. Every artist should make their space as fitting for themselves as possible. In my case, comfort and lack of interruption are key. While my studio may not be appealing to others, that's not what it was intended for. A high percentage of artists' studios look like a bomb went off in a paint factory.

Sir Fred Hoyle, an English astronomer and mathematician, once suggested metaphorically that the chances of life occurring by natural process would be similar to a tornado moving through a scrap yard and assembling a jumbo jet. In comparison, this is slightly off topic. I believe that an artist's studio, no matter how devastated it may be perceived, combined with an artist's talent, can assemble that jumbo jet on canvas. Once the lights are on and the music is right, I am in my element and in synergy with my surroundings. The focal point is before me, and the rest of the world goes away.

While your methods emphasize intuition, they are undergirded by decades of technical refinement. How do you reconcile spontaneity with mastery, particularly in a medium like oil painting that historically privileges control, revision, and deliberation?

While my methods emphasize intuition, they are not the only methods available to me. There is no rule in my studio that says I can't combine methods or change them altogether. Some artists throw paint on a canvas a few times and call it a day. I am not a one-day artist. My oils require quite a lot of deliberation and revision. They don't simply happen at the spur of the moment. Just because some of my thoughts might be spontaneous, my paintings certainly are not. Some take months to complete, and several have taken years.

Your proposed exhibition of damaged artworks reframes destruction as a site of possibility rather than loss. How does this project intersect with your broader interest in emergence? Do you see damage as another form of authorship that complicates conventional hierarchies between intention, accident, and value?

The proposed damaged art exhibition is one of those ideas that may never come to fruition under my hands, but if someone were to take the reins on that idea, I believe that it could be quite successful. Damage could be a form of authorship. In fact, to a minor degree, I believe that it already has. I'm not sure if it would stand the test of time or be a passing fad.

Hierarchies often tend to get a bit conservative when new forms of work enter their realm, but the potential for advancement and bragging rights continues to talk. Someone always has to take the first step. Consider the famous Banksy shredded artwork at Sotheby's. A full exhibition of this type would still need to show artistic merit of some sort, however. Throwing a piece of junk art on the floor or damaging a work on purpose may not show as much integrity as showing a piece of damaged work that can be appreciated for its origin, aesthetic, and overall composition.

In embracing abstraction and surrealism as vehicles for positivity, how do you navigate the risk of aestheticizing affect, of producing images that soothe rather than challenge? Is there, for you, a productive tension between visual pleasure and conceptual depth, or do you see them as fundamentally interdependent?

While my intentions for abstraction and surrealism are painted with positivity in mind, it doesn't mean that viewers might not completely misinterpret them into something completely negative, and for them, who's to say that it's a misinterpretation? No two people are going to read a single work of art identically. I don't feel any risk on my part, as I have already accomplished what I had intended to do. There can be a productive tension between visual pleasure and conceptual depth, but they can also meld together in certain circumstances. By design, my works seldom strive for the depth that is conceptual and tend to aim more for the depth of imagination. I believe that it helps expand the mind.

Your avoidance of eliciting specific viewer responses suggests a commitment to openness, yet you remain attentive to subconscious reception. How do you theorize the viewer’s role within this framework? Are they co-producers of meaning, witnesses to a private logic, or participants in a perceptual experiment that unfolds differently with each encounter?

I am completely open to the opinion of viewers, whether it be positive or not. My paintings are not produced in order to stop them from thinking for themselves. I just find it important that they connect with the piece without me interfering in the process. A person may be drawn deeply to a musician's music, but may have absolutely no interest or feel any connection to the person who performed it. Along those lines, I believe that the connection between the art and the viewer should at least be established first.

After that, if they wish to discuss it or know more about me, I'm completely open for comment. The occurrence of any detectable subconscious reception may or may not present itself at all. I just like seeing or hearing how people receive it, whether their reactions are positive or negative. It won't change how I work. I don't know that my logic will present itself well in the work because I don't always intend to be logical when making it. I do believe, however, that the viewers will always be co-producers, as their minds fill in a blank that I can't. That would be their final interpretation.

After periods of disengagement prompted by external demands, your return to painting appears grounded in self-determined purpose. How has this interruption reshaped your understanding of artistic labor, not merely as production, but as a long-form ethical practice that must remain answerable to the conditions under which it is made?

My period of disengagement was filled with decades of film and video production, whereby I still dealt with photography, color, composition, motion graphics, editing, deadlines, and deliverables. I also directed numerous live television programs, so clearly, it opened a broader understanding of artistic labor. I found it to be less of an interruption and more of an opportunity to practice with a different medium. When returning to painting, while simultaneously working in television, self-determination and purpose became more important due to time constraints. As I move closer to retirement from the television industry, I'm sure that the schedule will ease, but the floodgates will open with regard to working in the studio. At this point, I may also include more mixed media, digital, and sculpture work.

Arrival of Mithras

Basking

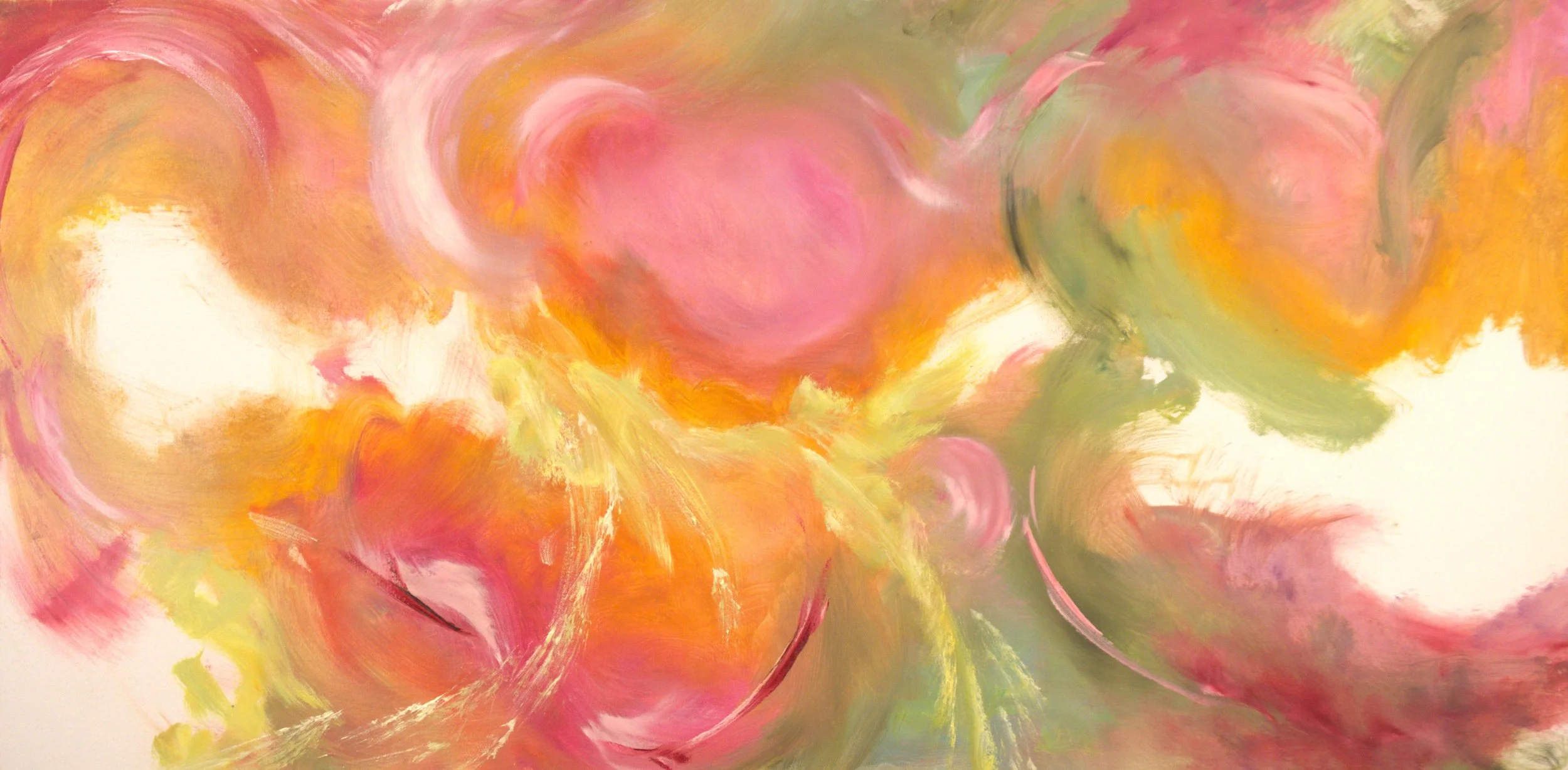

Brandied Fruit

Cashmere Lilting

DMT Launch Pad, Mixed Media, 24 x 30

Entering The Trance

Fathom That!

Interplanetary Carpe Diem

Lofty Waters

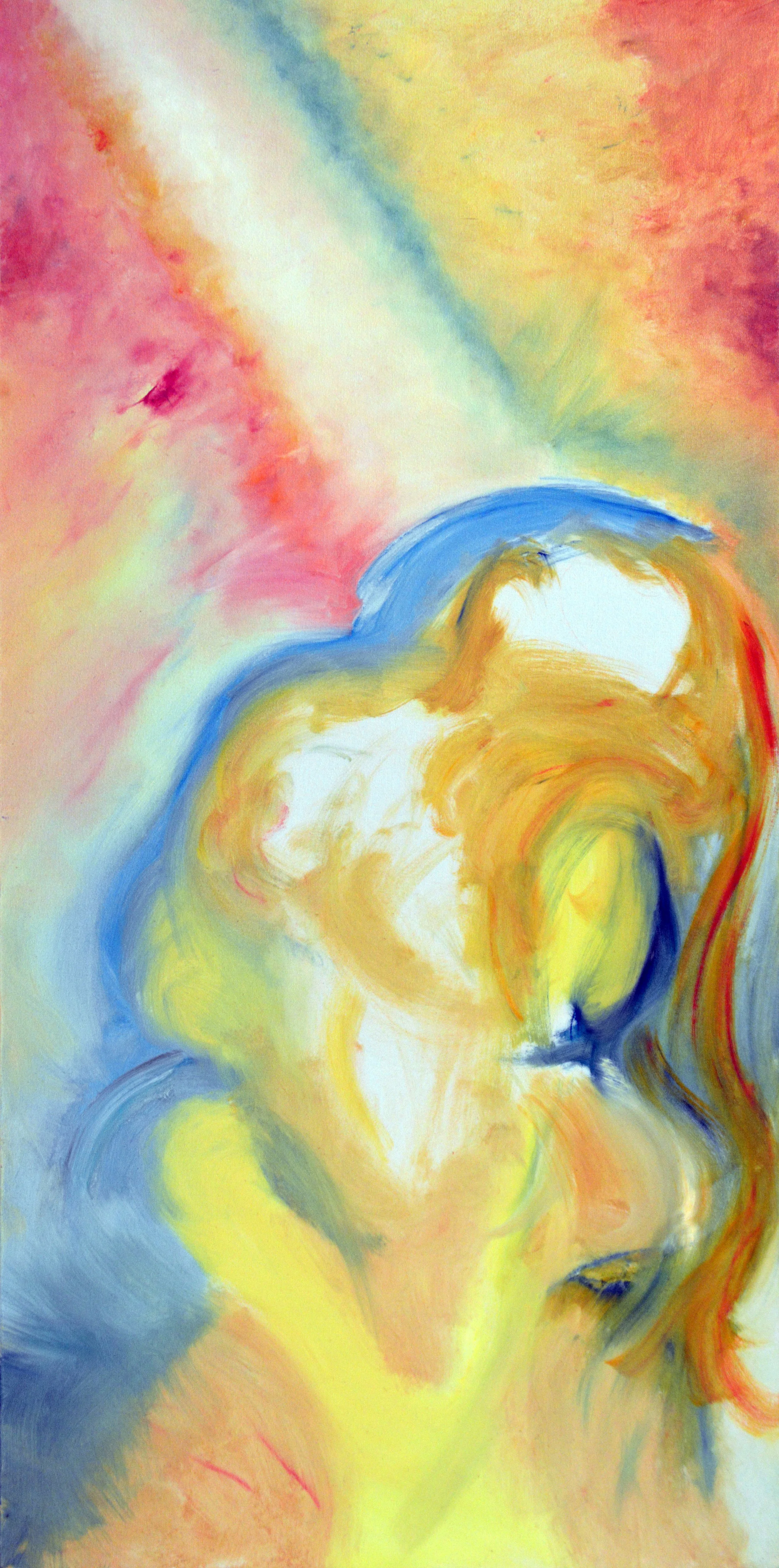

Primal Enlightenment, Oil on Canvas, 24 x 48

Silent Reverie

Taunting The Ringmaster

The Visitation

Twilight Vessel

Women, Spirit, and Earth