Interview with David Poyant

https://davidpoyantembroideries.com/

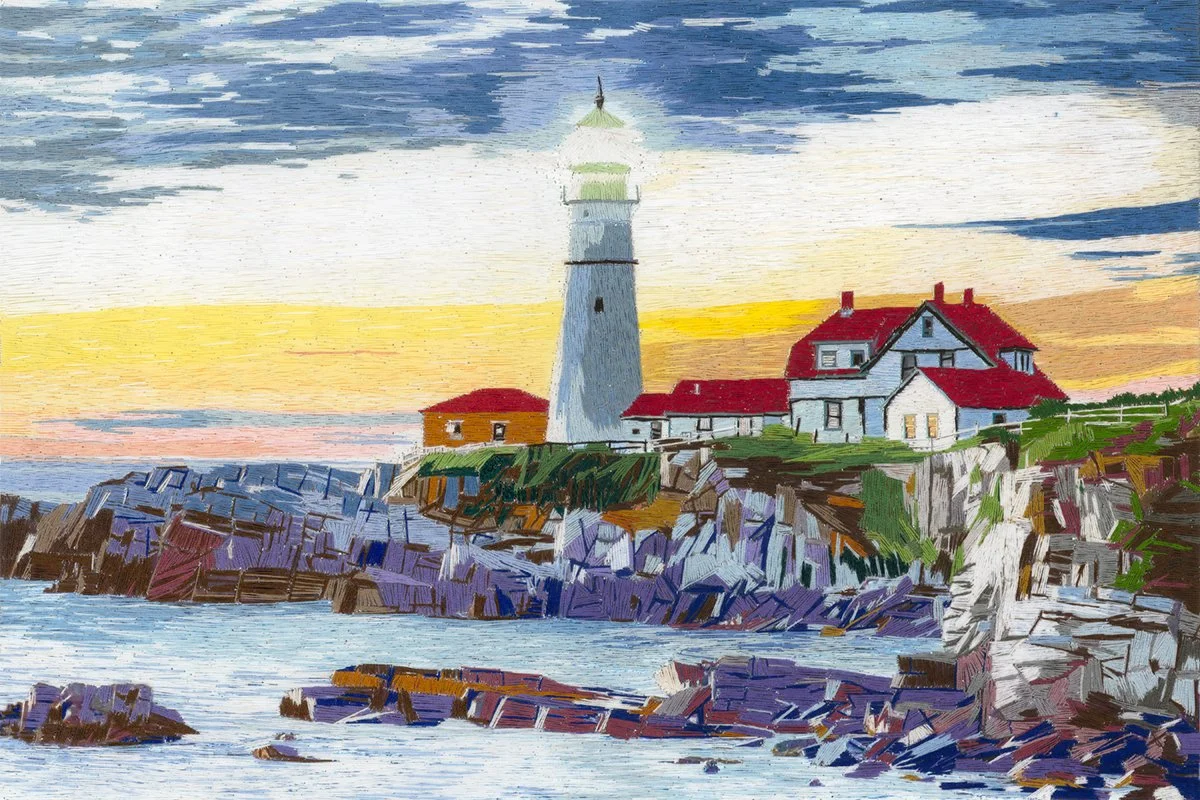

David Poyant is a contemporary embroidery artist whose work transforms the traditional craft of needlework into a powerful form of visual storytelling. Entirely hand-sewn, his pieces merge fine-art composition with the intimacy of textiles, creating richly textured worlds one stitch at a time. Beginning his artistic life later in adulthood, Poyant brings to his practice a deep sense of reinvention, memory, and lived experience. His decades as a cobbler and craftsman inform the patience, precision, and tactile sensitivity that define his work today.

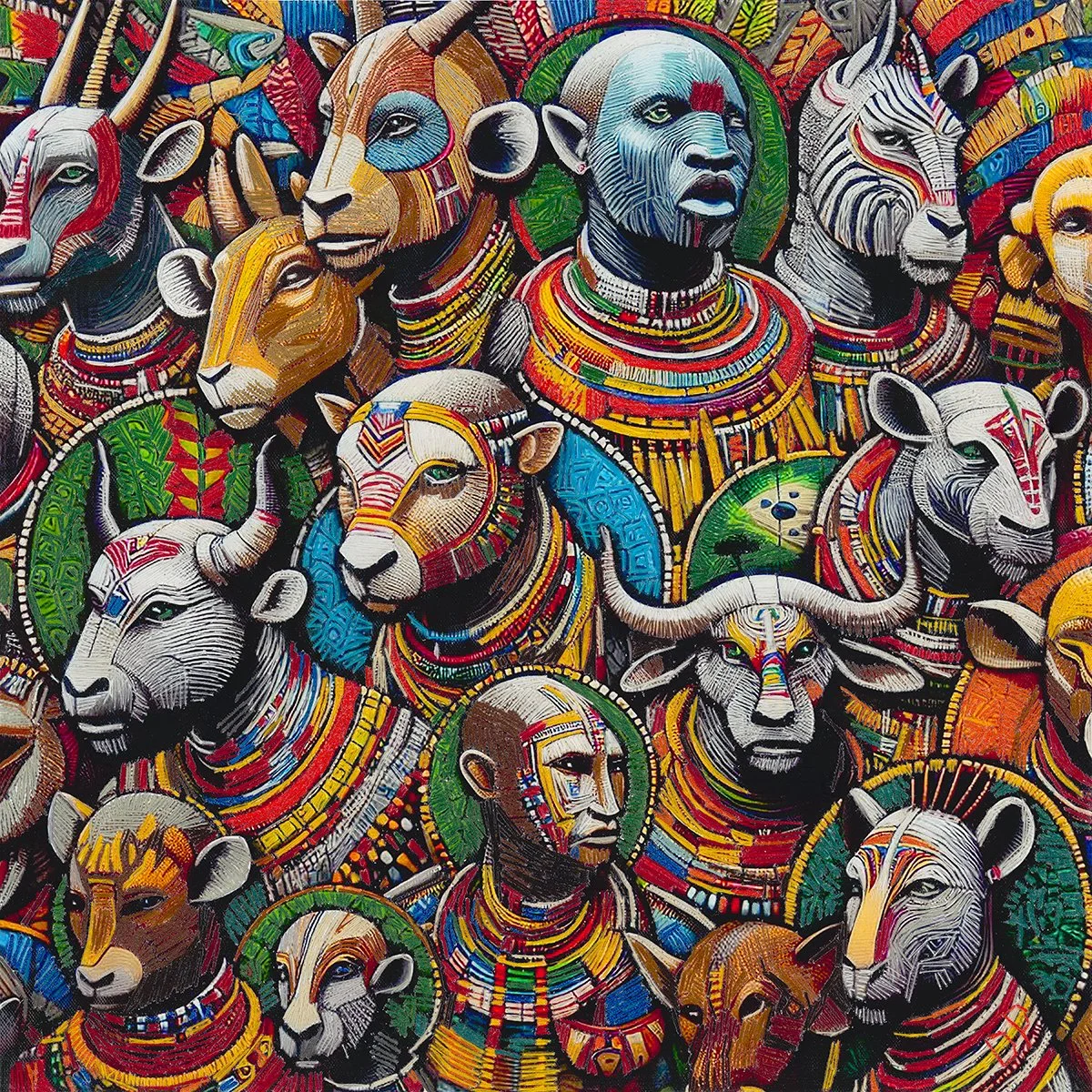

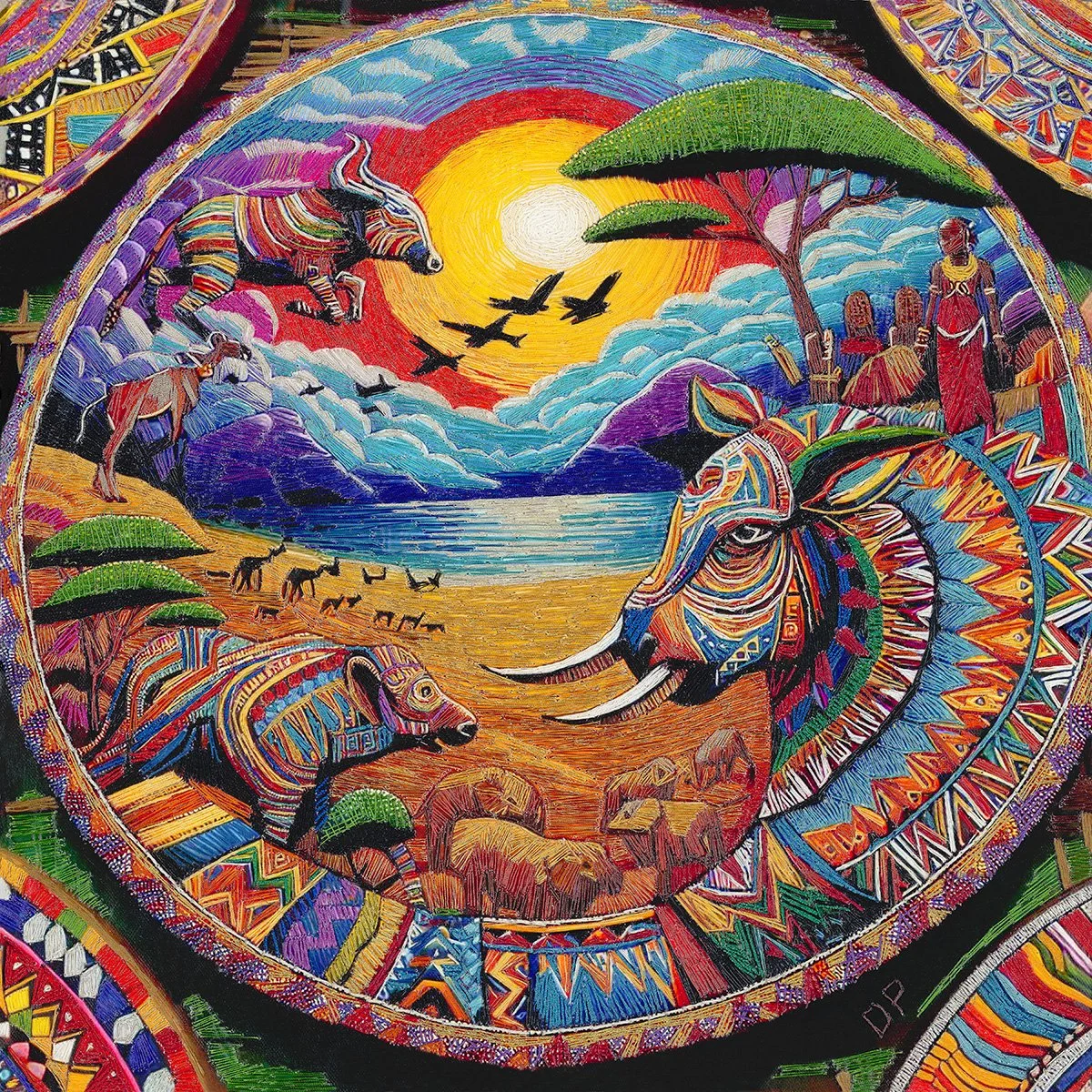

Poyant’s embroideries explore nature, nostalgia, culture, and the human journey, often drawing from personal history, coastal New England environments, and global influences—including his connection to the Maasai Tribe through his son’s service and honorary warrior status. Each piece is a narrative: a scene suspended in thread that invites viewers to pause, reflect, and feel the story beneath the surface.

His work has been featured by Artsy Shark, New Bedford Light, the Standard Times, and Art Matters, and exhibited at the New Bedford Art Museum, Gallery X, Soco Art Labs, The Narrows, The Collaborative, and international showcases including the Venice International Art Fair. Recognitions include the Exhibizone Grand Prize, Protagonist of Contemporary Art Award in Saint Paul de Vence, and the International Prize Côte d’Azur at the Musée National du Sport in Nice, France.

Blending tradition and innovation, Poyant embraces the evolving relationship between handcraft and technology, using AI in his creative development while preserving the irreplaceable human touch of hand embroidery. His art stands as an invitation—to slow down, to look closely, and to rediscover the wonder hidden in the smallest details.

David, your practice is rooted in what you describe as “slow craftsmanship,” a temporal philosophy that unfolds one stitch at a time. In an era increasingly defined by acceleration, automation, and the dominance of the instantaneous digital image, how do you conceptualize the temporality of your handwork as a critical gesture? Do you see the slow rhythm of embroidery as a resistance to contemporary velocity, or as a meditative counter-proposition to the art world’s obsession with constant production, and how might this temporal stance influence the viewer’s own experience of duration when encountering your work?

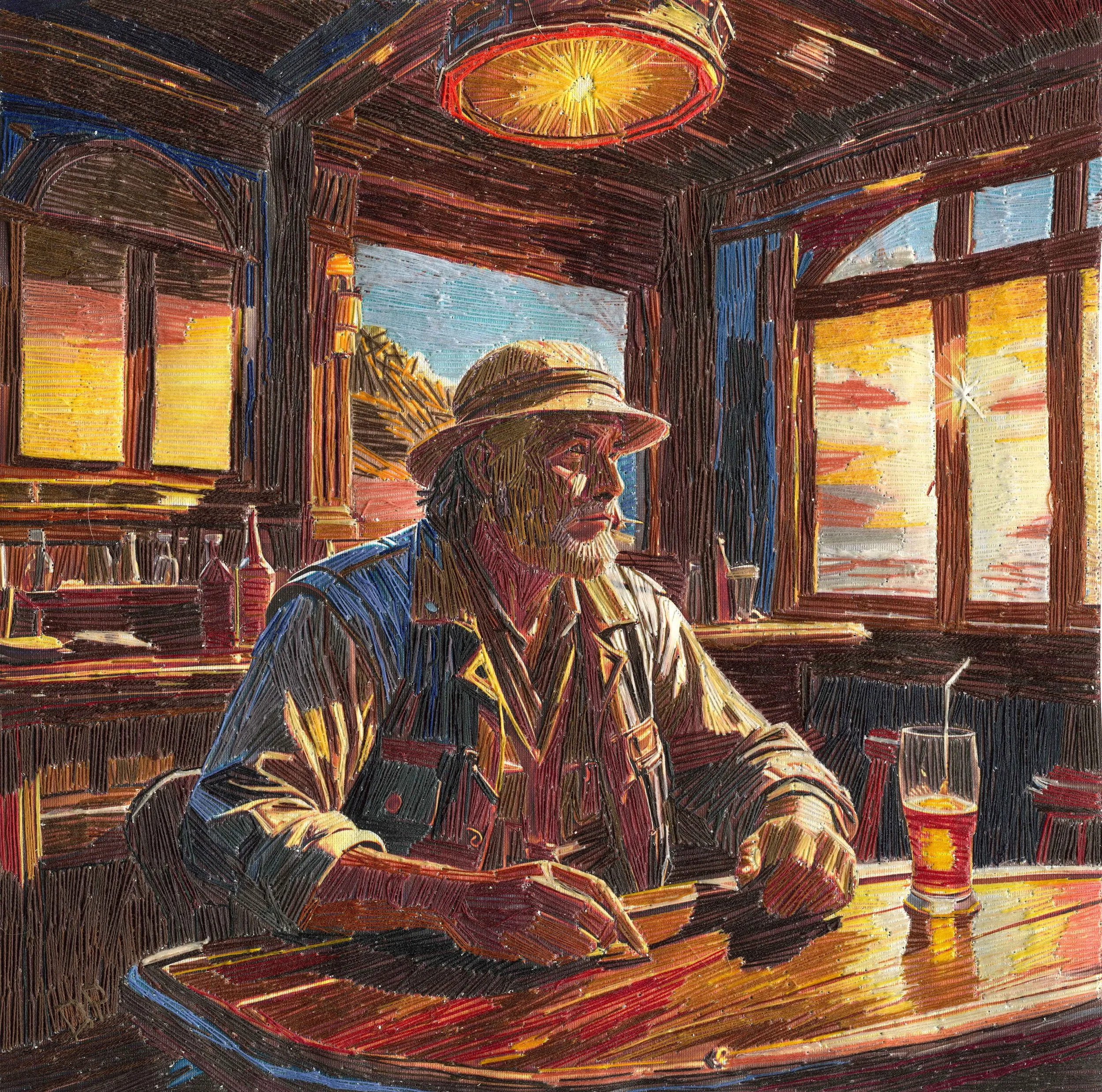

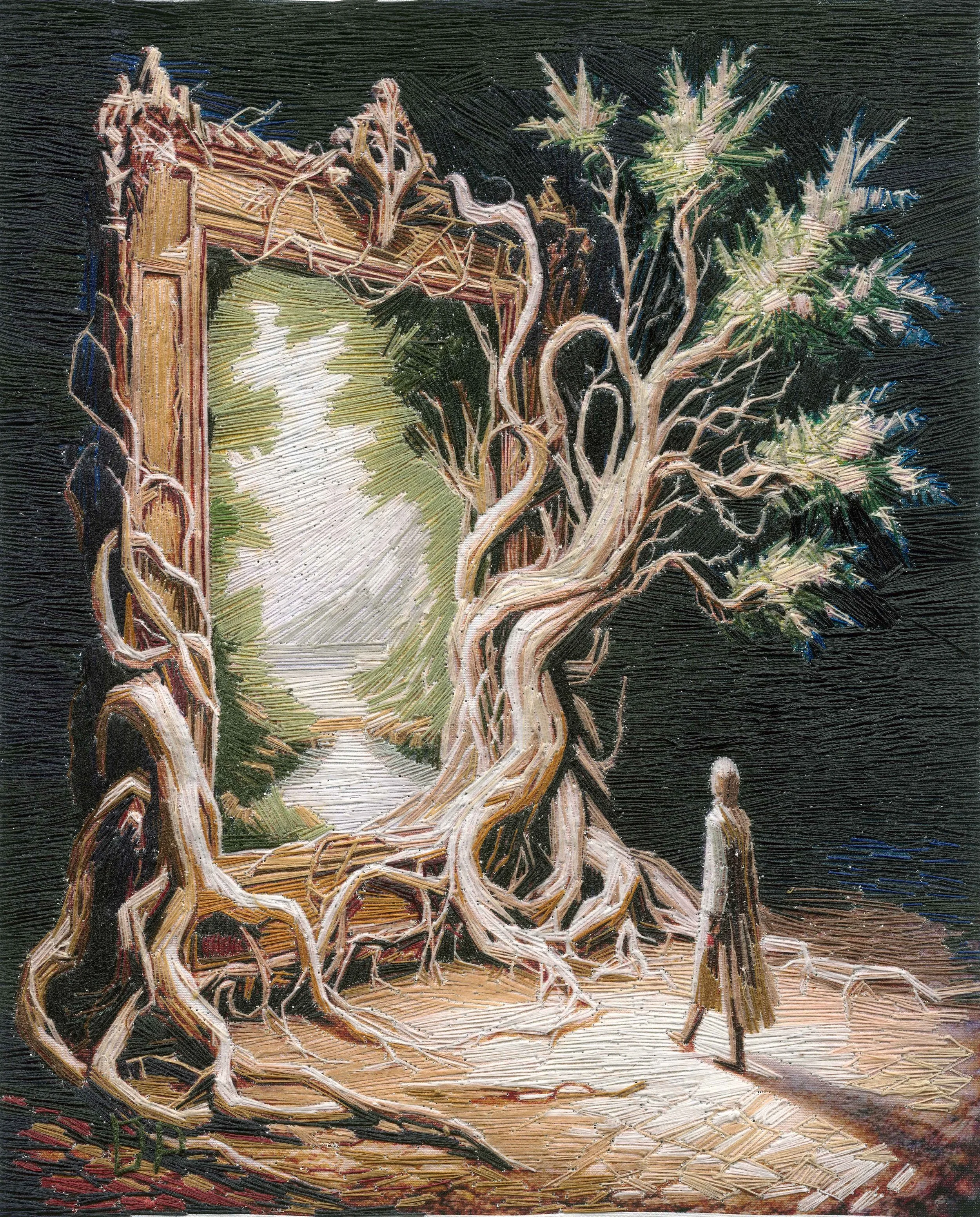

Embroidery is an act of deliberate slowness in a world that rarely pauses. I often describe my practice as “slow craftsmanship” because each piece truly does unfold one stitch at a time. In an era driven by acceleration and digital immediacy, I see my handwork as a quiet way of doing things differently. I’m not against technology—I use it as a creative tool—but hand stitching lets me keep a human pace, a rhythm that feels honest and grounded. The slow pace of hand embroidery gives my thoughts, memories, and stories time to sink into the work.

Every hour with the needle feels like a calm conversation between what I plan and what I discover. In that way, my process becomes a quiet, mindful contrast to the fast pace and constant pressure of the art world. Slowness gives the work a different kind of weight—one that isn’t measured in output, but in presence.

I believe viewers can feel that accumulated time when they stand before a finished piece. The density of stitches, the subtle shifts in color, the almost tactile sense of patience—all of it invites them to linger rather than glance. I hope viewers feel a little pause in time when they look at my work—a quiet moment like the one I feel while stitching. If my embroidery helps someone breathe a bit deeper, notice a bit more, and slow down even for a moment, then my “slow craftsmanship” has done what it’s meant to do.

Embroidery historically carries connotations of domestic labor, femininity, and the undervalued sphere of the “minor arts.” You have entered this lineage as a male artist, late in life, and without formal training. How do you reflect on the gendered and class-based histories embedded in the medium you have chosen? Do you see your work as participating in a reclamation of textile practices into the realm of high art, or as a rewriting of who is permitted to occupy the narrative of textile-based fine art?

Embroidery has a long history, shaped mostly by women whose work was important but often overlooked. As a man coming to this art later in life and without formal training, I am very aware that I’m entering a space built by generations of women. I try to approach that history with respect. I don’t see myself as changing it—I see myself as honoring it.

My mother sewed constantly when I was a child, and watching her work—quietly, patiently, with total focus—left a lasting imprint on me. When I began embroidering decades later, it felt less like choosing a medium and more like returning to something that had been waiting for me. That personal connection keeps me mindful of the gendered and class-based narratives embedded in textiles. It reminds me that the skill, discipline, and artistry of embroidery have always been present; they were simply overlooked.

I don’t claim to “reclaim” textile practices on behalf of anyone, because they were never lost—they were just underappreciated. I hope my work helps people think differently about where embroidery fits in the art world. By showing my hand-stitched pieces in galleries and international exhibitions, I’m part of a slow but important shift—reminding people that these “small” or “minor” arts have always carried real artistic power. At the same time, my own late entry into this medium—outside academic institution, outside traditional expectations—does rewrite a small part of the narrative. It suggests that textile-based fine art is not limited by gender, age, or formal training. It is a language available to anyone willing to sit with it, commit to it, and let it shape them.

If my work opens the door even a little—making room for more people, more stories, and more unexpected artists—then I see that as a good thing for a tradition that should be wide and welcoming.

Your collaboration with artificial intelligence to generate conceptual imagery introduces a provocative duality: algorithmic speculation on one side and the intensely tactile, labor-dense, corporeal act of stitching on the other. How do you negotiate the conceptual tension between technological abstraction and embodied making? Does the machine serve merely as a prompt for imagination, or has it become a silent coauthor that influences the direction, structure, or aesthetics of your compositions?

Working with AI doesn’t replace the handwork—it simply expands my imagination. AI lets me explore ideas quickly, in ways I could never sketch by hand. But that fast digital process is very different from the slow, physical rhythm of stitching. I don’t see the contrast as a problem; I see it as an exciting space where two different worlds come together. AI works in a world of ideas. It mixes, changes, and creates things endlessly, without getting tired or emotional. My work, on the other hand, is intensely tactile and embodied. Each stitch carries the weight of time, memory, and intention. When I translate an AI-generated idea into embroidery, I’m not simply copying a digital image—I’m interpreting it, questioning it, slowing it down until it becomes something human again.

AI is more than just a prompt, but not a full collaborator either. It’s like a quiet partner that suggests ideas, but the final artwork is still shaped by my hands. AI can inspire a new color choice, a different layout, or an unexpected detail—but it can’t give the piece its soul. That comes from the time, effort, and human touch that go into every stitch.

What I love about working with AI and embroidery together is that it reflects what’s happening in art today, the mix of digital and handmade, fast and slow, future and tradition. AI helps to imagine the ideas, and my hands bring them to life. The finished piece becomes a bridge between those two worlds. I think viewers can feel both—the quick spark of technology and the deep, human touch in every stitch.

Much of your work engages themes of nature, nostalgia, and human experience, yet your process is deeply indexical and material. How do you understand the relationship between the narrative and emotional content of your work and the physicality of the thread itself? Do you consider the thread as a symbolic extension of memory and lived experience, or does the material operate more like a phenomenological surface where stories accumulate stitch by stitch?

The stories and feelings in my work are directly connected to the thread itself. The stories I stitch—memories of childhood, echoes of the natural world, moments of wonder or quiet reflection—don’t sit on the surface of the fabric. They emerge through the material. Thread isn’t just a material to me — it has its own way of speaking through its weight, texture, and rhythm. I often think of each strand of thread as a kind of memory filament. It carries the touch of my hands, the hours spent in concentration, even the small hesitations or shifts in mood that shape the stitch. In that way, the thread becomes a part of my life experience—and invites the viewer into that feeling too. The material holds time, much like a memory does. At the same time, I think of the fabric as a place where the story builds slowly. Each stitch is a small mark of time, a moment recorded by hand.

As the stitches add up, they create the scene—a forest, a sky, a figure, or even just a feeling. I don’t always know the full story when I start. It develops as I work, growing one stitch at a time through both planning and discovery. What the viewer sees is a mix of the image itself and the signs of how it was made. The thickness of the thread, the slight changes in tension, and the way the colors blend by hand are all part of the work’s heartbeat. These details encourage the viewer to slow down, notice the time in the stitches, and feel the human presence in every bit of the piece. So yes, the thread works in two ways. It holds memories, and it’s also just a material. It carries the story, and it shows the process. When those two things meet, that’s where the artwork finds its voice.

Your biography presents a radical inversion of the canonical artist narrative. You began creating at sixty-six, long after most artists have solidified their aesthetic language. How does coming to art later in life shape your understanding of artistic identity, authorship, and legitimacy? In what ways does your lived experience as a cobbler and craftsman inflect your visual language, and do you believe your previous occupations have provided you with a sensibility unavailable through academic training?

Starting my art career at sixty-six changed how I see myself as an artist. I didn’t come to art through school or a traditional path—I came through years of working with my hands and living my life. Beginning so late freed me from the pressure to fit into any set style. I didn’t have to search for my voice; it had been growing quietly for years, shaped by everything I’d already done. My years as a cobbler and craftsman are not separate from my art—they are the foundation of it. Working with leather, repairing shoes, and understanding how materials behave under pressure taught me patience, precision, and respect for the tactile world. Those trades demanded close attention to detail, an instinct for structure, and a commitment to solving problems with my hands. All of that translates directly into how I treat thread and fabric. I think in textures, in weight, in tension, in durability. I’m always aware of how something is built.

Because of my past jobs, I see and feel materials in a way I don’t think formal training could teach. Those years of steady, hands-on work showed me that beauty often comes from quiet, repeated effort. They taught me to appreciate small gestures—like how a single stitch can carry a story, just as a repaired shoe carries the memory of every step it’s taken.

Coming to art later in life also means I no longer question legitimacy. My legitimacy isn’t rooted in institutional validation; it’s rooted in lived experience, in the courage to begin again, and in the trust that a lifetime of craft has prepared me for this moment. Every stitch I make carries the history of who I’ve been—cobbler, worker, father, observer—and the artist I’ve allowed myself to become. In that way, my work is not a departure from my past, but the natural continuation of it, finally expressed in a medium capable of holding its emotional weight.

Your Thread Paintings oscillate between representation and abstraction, between the pictorial logic of traditional paintings and the textural logic of fiber. How do you navigate the threshold where embroidery ceases to be merely textile and becomes painterly? Do you conceive your work within the lineage of painting, or do you position it as a distinct modality that challenges the hierarchical distinctions between media?

My Thread Paintings live in the space between embroidery and painting. The thread sometimes acts like paint, but it never stops being fiber. Finding that balance is one of the most interesting parts of my work. I’m always deciding how much the piece should look like a picture—light, shadow, atmosphere—and how much it should show the texture and weight of the thread itself. Even when the image feels painterly, the surface always reminds you that it’s stitched, textured, and handmade. I don’t think of embroidery as “imitating” painting; instead, I’m asking what happens when the logic of painting is translated through material that has its own rules. Thread forces decisions that paint never would. It resists certain movements, demands repetition, and records time in a way that brushstrokes cannot. When I’m working, I’m aware of both traditions—painting’s visual language and fiber’s tactile one—and my pieces emerge from the tension between them.

In some ways, my work connects to painting, but it’s only one part of a bigger picture. I use the depth, composition, and storytelling that painting offers, but the medium of thread naturally challenges the old divide between “fine art” and “craft.” I’m not trying to make embroidery look like painting—I want to show that fiber has its own power and doesn’t need to imitate anything else to be seen as real art. In the end, I see my work as its own form, something that sits between categories rather than inside them. By blending painting-like ideas with fiber, I’m asking viewers to rethink what painting can be, what textiles can be, and how the lines between them can fade. The back-and-forth between image and material, between realism and abstraction, is where my work speaks—and where it gently challenges the old rules of the art world.

The Hand Made History series, along with your works inspired by Maasai art and your personal connection through your son being honored as a Warrior, gestures toward global cultural narratives. How do you approach questions of cultural translation, ethical representation, and narrative responsibility when embroidering motifs from cultures with deep aesthetic and spiritual traditions? What internal dialogues guide you as you transform these references into contemporary textile artworks?

When I work within the Hand Made History series or draw inspiration from Maasai aesthetics, I do so with a profound sense of responsibility. These designs aren’t just random cultural symbols to me. They come from real relationships—through my son being welcomed as a Warrior and through the stories and kindness shared with him and our family. That personal connection guides me. It reminds me that I’m working with traditions that hold deep spiritual, historical, and community meaning. Sharing elements from another culture is never simple, and I’m very aware of that. I’m not trying to copy or claim something that isn’t mine—I’m trying to interpret it with respect. I see myself as a storyteller working in thread, not as someone speaking for a culture. So I constantly ask myself:

Am I honoring the spirit, not just the look?

Am I respecting where these traditions come from?

Am I adding something meaningful, or just taking? Respect guides every decision—the colors I choose, the symbolism I reference, the way I frame the narrative accompanying the work. I research, I listen, and I remain mindful of what is mine to depict and what must remain sacred.

Being respectful also means being clear about my role. I never call my pieces “authentic Maasai art,” because that would ignore the real artists who carry those traditions. Instead, I describe them as modern textile works inspired by Maasai colors and patterns, shaped by my own experience as a father, an artist, and someone who has watched a meaningful cross-cultural connection touch my family. Thread helps me navigate this terrain. It slows everything down. Embroidery is a medium of humility—it asks me to sit with the subject, to consider its weight, to approach it with reverence rather than speed. Stitching becomes a form of contemplation, a way of acknowledging the magnitude of the stories I’m touching.

In the end, my decisions come from gratitude, respect, and a wish to build connections, not divide. I want my work to show appreciation, not ownership—to reflect connection, not taking. My goal is to honor the people and traditions that inspired me while still staying true to my own artistic voice.

Your work has been recognized across international platforms, from Massachusetts to Nice, Saint-Paul de Vence, and Italy. As your practice continues to expand geographically and conceptually, how do you understand the global resonance of embroidery in contemporary art? Do you think textile art is undergoing a redefinition within the international art market, and how do you situate your work within this broader shift toward valuing materiality, tactility, and handwork?

As my work has traveled from Massachusetts to France, Italy, and other international platforms, I’ve been struck by how deeply embroidery resonates across cultures. Thread is a universal language. Every region of the world has some history of textile making—whether utilitarian, ceremonial, or artistic—so viewers arrive with an instinctive familiarity, even if the imagery is new. I think that shared material lineage creates a powerful entry point into contemporary conversations about art, memory, and human labor.

Globally, textile art is undergoing a profound redefinition. What was once dismissed as “decorative” or “domestic” is now recognized as a site of conceptual rigor, material innovation, and cultural dialogue. Collectors, curators, and institutions are paying attention to tactility again—to the hand, to process, to slowness in a world saturated with speed. I see this shift as both overdue and deeply meaningful. Embroidery has always been a sophisticated visual language; the art world is simply catching up.

I see my work as part of this global shift and also as something personal. I want to honor the handmade, celebrate patience and craft, and give viewers a real, physical sense of time. In today’s digital world, the weight and presence of a hand-stitched surface can feel surprisingly powerful.

The international reception of my work reinforces that people everywhere are hungry for art that holds a human pulse—art that embodies hours, care, and lived experience. As my practice expands geographically and conceptually, I hope to contribute to this broader revaluation of fiber-based art, showing that embroidery is not a secondary medium but a contemporary force capable of narrative depth, emotional resonance, and global relevance.

Embroidery inherently invites intimacy. Viewers approach it differently than they might approach a painting, often leaning closer, attuning themselves to scale, detail, and texture. In composing your pieces, do you intentionally choreograph this intimacy? How do you consider proximity, surface, density of stitch, and the tactile allure of thread as tools for shaping the viewer’s psychologycal and emotional engagement?

Embroidery creates an intimacy that is different from any other medium, and I’m very conscious of that when I compose a piece. Unlike a painting, which can often be read from a distance, embroidery pulls the viewer in. It asks them to lean closer, to slow their breathing, to let their eyes adjust to scale, texture, and density. That physical closeness becomes part of the emotional experience, and I choreograph that intentionally.

Proximity is one of my key tools. I think about how a piece looks from far away—just color, mood, or story—and then how it changes as someone walks closer. Up close, the viewer can see and feel the details: the threads, the stitch patterns, the way light hits the fibers. I want that slow approach to be an invitation into a more intimate private world. Stitch density is a big part of how I guide the viewer’s experience. Heavy stitching adds weight and intensity—it feels full of time. Lighter areas give the eye a place to rest. These changes across the surface help lead the viewer’s gaze and create an emotional rhythm, almost like telling a story through texture.

Thread naturally draws people in. Its warmth, softness, and small imperfections all add to the intimate feeling of the work. I think a lot about how texture affects the viewer—a smooth area of blended color can feel calm, while a raised or rough section can create tension or mystery. Even the direction of the stitches can set the mood. In many ways, I’m choreographing an encounter. I want viewers to take their time with each piece, the same way I did while making it—slowly and with focus. When someone leans in close, they’re stepping into the quiet space where the work was created. They’re meeting the hours, the patience, and the human touch stitched into every thread.

If my art gives someone a quiet, intimate moment—if it helps them pause and slow down—then I feel I’ve done what I set out to do.

In many ways, your practice embodies a profound narrative: reinvention, intergenerational memory, and the discovery of artistic voice at a moment traditionally associated with retirement. How do you see your personal story interacting with the conceptual foundation of your work? Do you view your art as an autobiographical journey stitched into color and form, or as something that transcends the personal and becomes part of a larger discourse on transformation, resilience, and the capacity for art to emerge at any stage of life?

My personal story is a big part of my art. Starting this work at a time when most people are slowing down has shaped both how and why I create. Reinvention, memory, and finding my voice later in life aren’t just themes—they’re the heart of what I do. Each piece is a reminder that creativity doesn’t fade with age. It can spark at any time, and the later chapters of life can be just as powerful as the early ones.

At the same time, my work isn’t just about my life story. Yes, you can find pieces of my childhood, my mother’s sewing, my years as a cobbler, and my family in the stitches. But the art isn’t meant to be a picture of my life. It’s meant to express the things life has taught me—patience, resilience, curiosity, and the courage to start over.

So, the personal becomes a doorway, not a boundary. Once a piece is stitched, it starts to belong to a larger conversation about transformation and possibility. I’ve come to realize that my story resonates because it challenges the expectation that artistry must be cultivated early, or that legitimacy comes only through formal training. My practice suggests something else: that craft, memory, labor, and lived experience can bloom into artistry at any moment, and that the human spirit is capable of reinventing itself far beyond the timelines we’re taught to expect.

In that way, my art goes beyond my personal story. It becomes part of a larger conversation about creating, adapting, surviving, and growing. If my work helps someone realize that their own story isn’t over—or that something beautiful can begin later in life—then it has done more than just tell my story. Each piece is both personal and universal: it reflects my journey, but it also invites others to see their own possibilities.