Daniel McKinley

The art of Daniel McKinley unfolds within a paradox. It is at once confined and boundless, meticulously constructed yet open to infinite interpretation. In his oil paintings, walls and windows, stairs and corridors, cities and interiors coexist in an ambiguous geometry of mind and space. To enter McKinley’s world is to move through layers of perception, to navigate not only physical structures but the architecture of consciousness itself. His paintings, rigorous in composition and rich in atmosphere, engage the viewer in a dialogue between presence and absence, the seen and the imagined, the finite and the eternal.

McKinley’s artistic journey began in the collision between dissatisfaction and wonder. Born with an instinctive resistance to the confines of convention, he approached art as both rebellion and revelation. His early encounters with museums and books, with the worlds contained within their walls and pages, shaped his understanding of art as a means to transcend limitation. From the outset, McKinley sought not merely to represent but to reimagine, to construct spaces that would allow the imagination to breathe. His education at the School of Visual Arts in New York City and Orange Coast College in California refined his technique but never tamed his curiosity. For McKinley, art remains an act of perpetual discovery. “I am never sure where my next painting will take me,” he says. “I only know that I must continue.”

This open-ended philosophy manifests vividly across his oeuvre. Each painting becomes a question, a threshold leading somewhere just beyond comprehension. His works often feature built environments such as rooms, façades, courtyards, and landscapes that oscillate between the familiar and the metaphysical. Through their quiet precision and dreamlike spatial logic, these compositions recall the visionary spaces of Giorgio de Chirico, whose metaphysical cityscapes transformed architecture into a stage for introspection. Yet McKinley’s world differs in tone. Where de Chirico’s plazas evoke the silence of enigma, McKinley’s interiors hum with the resonance of reflection. His spaces are not desolate but contemplative, inviting the viewer into participation rather than estrangement.

In Comfort (2002), a golden armchair occupies the lower right corner, its rounded form echoing the warmth of human presence. The adjacent wall, rendered in meticulously articulated brickwork, divides the composition into zones of interior and exterior. Beyond an open frame, a green field stretches beneath a pale sky, bisected by a golden path that recedes into the horizon. The painting’s precision of line and luminous palette suggest order and serenity, yet the juxtaposition of domestic enclosure and vast landscape introduces tension. What is comfort, McKinley seems to ask, if not a kind of containment? The chair invites rest, but the distant horizon beckons. Between the two unfolds the drama of human consciousness, forever oscillating between security and yearning.

The motif of the threshold recurs in Entrance to Exit, a composition structured around the dialectic of confinement and passage. A vertical column of red tiles and classical arches frames a narrow view of an open road leading toward distant forms. The path, rendered with a single vanishing line, draws the eye forward into infinity. The image operates simultaneously as interior décor and metaphysical allegory. Every enclosure contains an aperture, every boundary a possibility of escape. In this dialogue between near and far, McKinley’s brush articulates an existential geometry, a visual meditation on the tension between the known and the unknown.

Spatial inquiry takes on a more domestic resonance in Portrait of the Interior, where a sequence of rooms unfolds through open doors and corridors. Warm tones of ochre, red, and sienna envelop the viewer in a psychological intimacy. Objects such as a chair, a lamp, and a bowl of fruit are rendered with the clarity of remembered experience. Yet each passageway leads deeper into mystery, perspective becomes a metaphor for introspection. The painting recalls the calm precision of Pierre Bonnard’s interiors and the psychological architecture of Edward Hopper, but McKinley’s use of space is more relational than solitary. His rooms are not depictions of isolation but of reflection, spaces where light becomes thought and furniture becomes memory.

In Gallery (2024), McKinley turns the act of viewing into his subject. A spiral staircase ascends into shadow while a table lamp glows against a wall of paintings within paintings. The nested frames, images within images, create a recursive dialogue between representation and perception. The viewer, caught in this visual loop, becomes aware of their own act of looking. It is a composition about consciousness itself, about the infinite regress of thought observing thought. The luminous Tiffany-style lamp at the center radiates both literal and symbolic light: art as illumination, understanding as interior brightness. Rosalind Krauss once wrote that “the grid functions to declare the autonomy of the aesthetic domain,” yet McKinley’s grid of rooms and frames functions differently. It opens the aesthetic domain toward infinity.

This fascination with recursion and reflection culminates in Framed Within (2023), where architectural forms are themselves enclosed by frames that echo one another in rhythmic succession. Here, McKinley transforms perspective into philosophy. Each painted frame is both a boundary and an invitation, a gesture of containment that paradoxically reveals the possibility of boundlessness. The repetition of architectural motifs such as arches, columns, and pathways creates a visual fugue that resonates with Piranesi’s labyrinthine prisons, but without their darkness. McKinley’s spaces are illuminated by an inner clarity, as if the act of framing were also an act of freeing.

The metaphysical dimension of his work finds a lyrical expression in Far and Away (2014). A luminous shoreline stretches into distance beneath a vast green sky. The horizon glows with a surreal intensity, and a solitary figure, a mere silhouette, walks along the sand. The proportions are cosmic, the solitude profound. Yet the atmosphere is not bleak; it is meditative. McKinley’s landscape becomes a mirror for the soul, a site where scale itself becomes metaphor. In its chromatic depth and serene expansiveness, Far and Away recalls the transcendental quietude of Caspar David Friedrich, but filtered through a distinctly modern consciousness. The landscape is no longer a symbol of divine order but of inner inquiry, the vastness of the self reflecting the vastness of nature.

With Just a Building (2005), McKinley turns to the façade as subject. A symmetrical arrangement of windows, arches, and columns is painted in rich sienna tones, its monumental stillness evoking both Renaissance order and metaphysical disquiet. The title’s understatement, “just a building,” is ironic; what we see is architecture as psychology. The repetitive forms and receding central corridor create a sense of infinite depth, a tunnel into thought. The viewer is invited to question not what the building is, but what it represents: the structures of memory, the architecture of time. In McKinley’s vision, every wall holds an echo, every window a glimpse of another world.

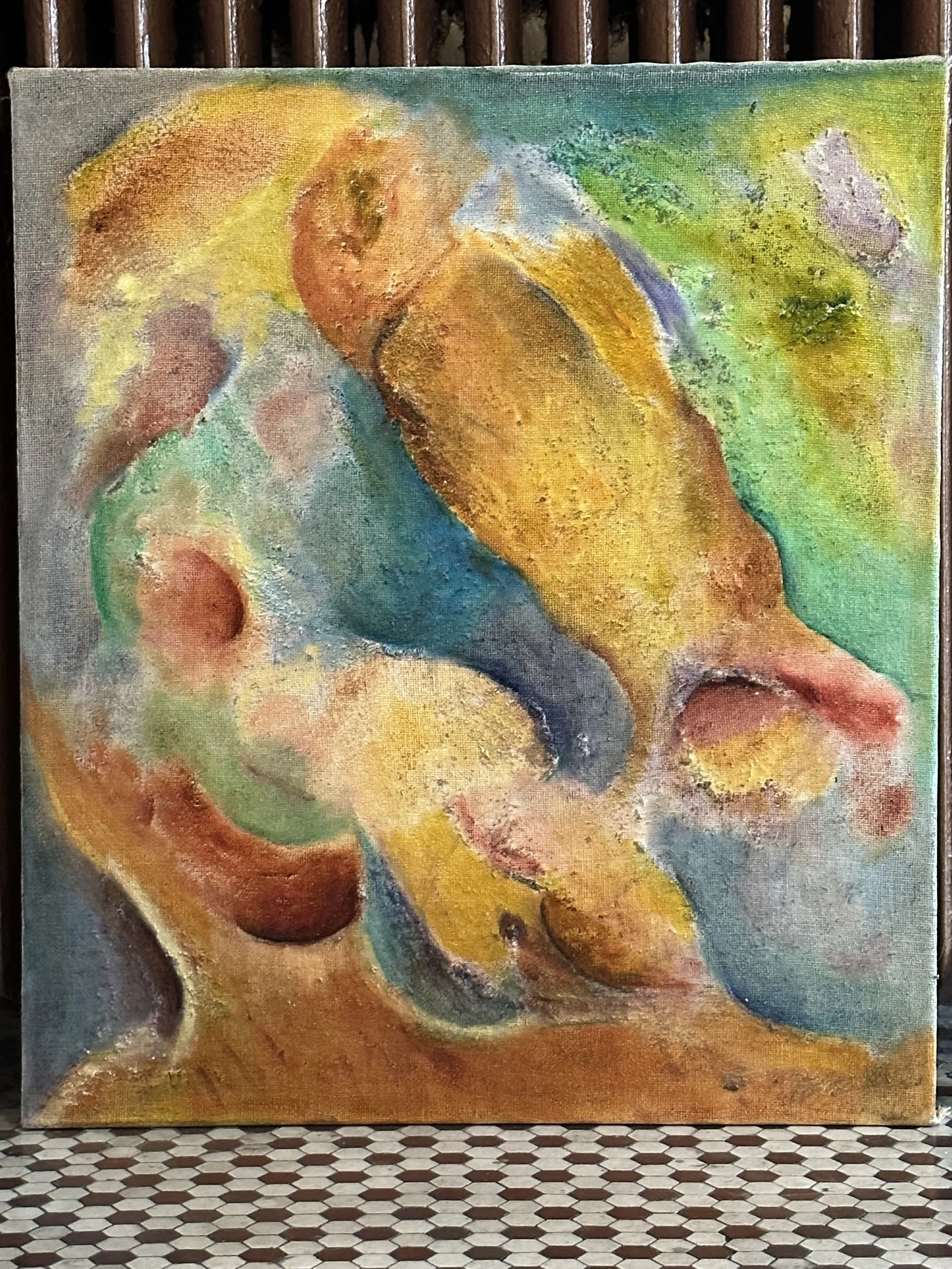

The dialogue between structure and abstraction is further developed in Working Still (2023) and Open Possibilities(2025). The former, dense with architectural motifs, organizes its space through intersecting planes of gold and crimson. Columns rise like ideas given form, corridors open into multiplicity. The painting suggests not a single perspective but a network of interrelated viewpoints. Open Possibilities, true to its title, moves toward greater abstraction, dissolving solid structures into fluid forms. Here McKinley’s geometry becomes organic, his colors atmospheric. The painting seems to vibrate between material and immaterial, between architecture and energy. It represents the artist’s evolution toward a more intuitive mode of expression, where composition emerges not from design but from discovery.

McKinley’s Gallery and Working Still also reveal his mastery of color as structure. His palette of warm ochres, deep reds, verdant greens, and radiant golds creates both solidity and transcendence. Each hue is carefully modulated to balance form and feeling. The interplay of tone and light suggests the influence of Italian Quattrocento frescoes, filtered through the metaphysical restraint of modernism. The precision of his line evokes architectural draftsmanship, yet his surfaces breathe with painterly life. This fusion of control and intuition defines his visual language.

If McKinley’s work invites comparison to de Chirico, it also aligns with the spiritual geometry of Paul Klee and the psychological depth of Hopper. Like Klee, McKinley transforms the grammar of architecture into a syntax of emotion. Like Hopper, he understands that space is a mirror of solitude. Yet unlike both, McKinley’s sensibility is neither melancholic nor whimsical; it is philosophical. His spaces are not stages for alienation but laboratories for thought. He constructs not walls but portals, not enclosures but meditations on openness.

Philosophically, McKinley’s art arises from the conviction that creation is a process of continual becoming. “We are taught to pick one area of work, create, repeat,” he observes. “My mind wanders. My work is not traditional. My work is based upon infinite possibilities.” This statement encapsulates the core of his practice: a refusal to be confined by style or subject. Each painting is a new inquiry, a fresh negotiation between imagination and structure. His approach mirrors the modernist search for autonomy while embracing postmodern multiplicity. In Krauss’s terms, McKinley occupies the expanded field of painting, his canvases are not simply pictures but propositions, each one redefining what painting can be.

Within the contemporary art scene, McKinley stands apart from both the cold conceptualism of much current production and the decorative superficiality of visual trends. His art offers neither ironic detachment nor empty spectacle. Instead, it returns to painting as thought, as architecture of the mind. In doing so, he reclaims the contemplative function of art, restoring its capacity to provoke, to console, and to enlighten. His compositions remind us that to look deeply is itself a creative act, that every image, when truly seen, becomes a mirror.

Societally, McKinley’s art speaks to the experience of living within constructed worlds, physical, social, and psychological, and the human desire to move beyond them. His paintings of interiors and façades mirror our own existence within systems of confinement and perception. Yet they also offer hope: every wall contains a window, every path leads to another horizon. His work invites viewers to rediscover their own sense of possibility, to recognize the infinite within the finite.

In the evolution of his oeuvre, from the early structured compositions of Comfort and Just a Building to the more fluid and exploratory Open Possibilities, one perceives a movement from mastery toward freedom, from precision toward revelation. It is the trajectory of an artist who understands that discovery requires uncertainty. McKinley’s paintings are not statements but journeys, not conclusions but continuations.

Daniel McKinley’s contribution to contemporary art lies in his capacity to fuse intellect with intuition, architecture with emotion, order with openness. His canvases, poised between realism and abstraction, contain entire philosophies of space and consciousness. They remind us that the greatest structures are built not from stone or pigment, but from thought and imagination.

To stand before one of his paintings is to stand at the threshold of the mind itself, where every wall becomes a question and every horizon an answer waiting to be found.

In that sense, Daniel McKinley’s art fulfills its deepest purpose. It does not show us where to look but teaches us how to see.

By Marta Puig

Editor Contemporary Art Curator Magazine

Open Possibilities 2025

Just A Building. 2005

Portrait of the Interior. 2014

Entrance to Exit. 2010

Gallery. 2024

Working Still. 2023

Comfort. 2002

Framed Within.. 2023

Far and Away. 2014

Movement. 2024