Becker Schmitz

By Emanuel Mir

It is no easy task to describe the extremely heterogeneous work of Becker Schmitz in a few brief sentences. First of all, it is not possible to say clearly whether the work of the Duisburg-based artist is to be classified as “painting”, “installation” or “site-specific intervention”. He takes great pleasure in hopping from one genre to the next and refuses all one-dimensional, constricting categorizations.

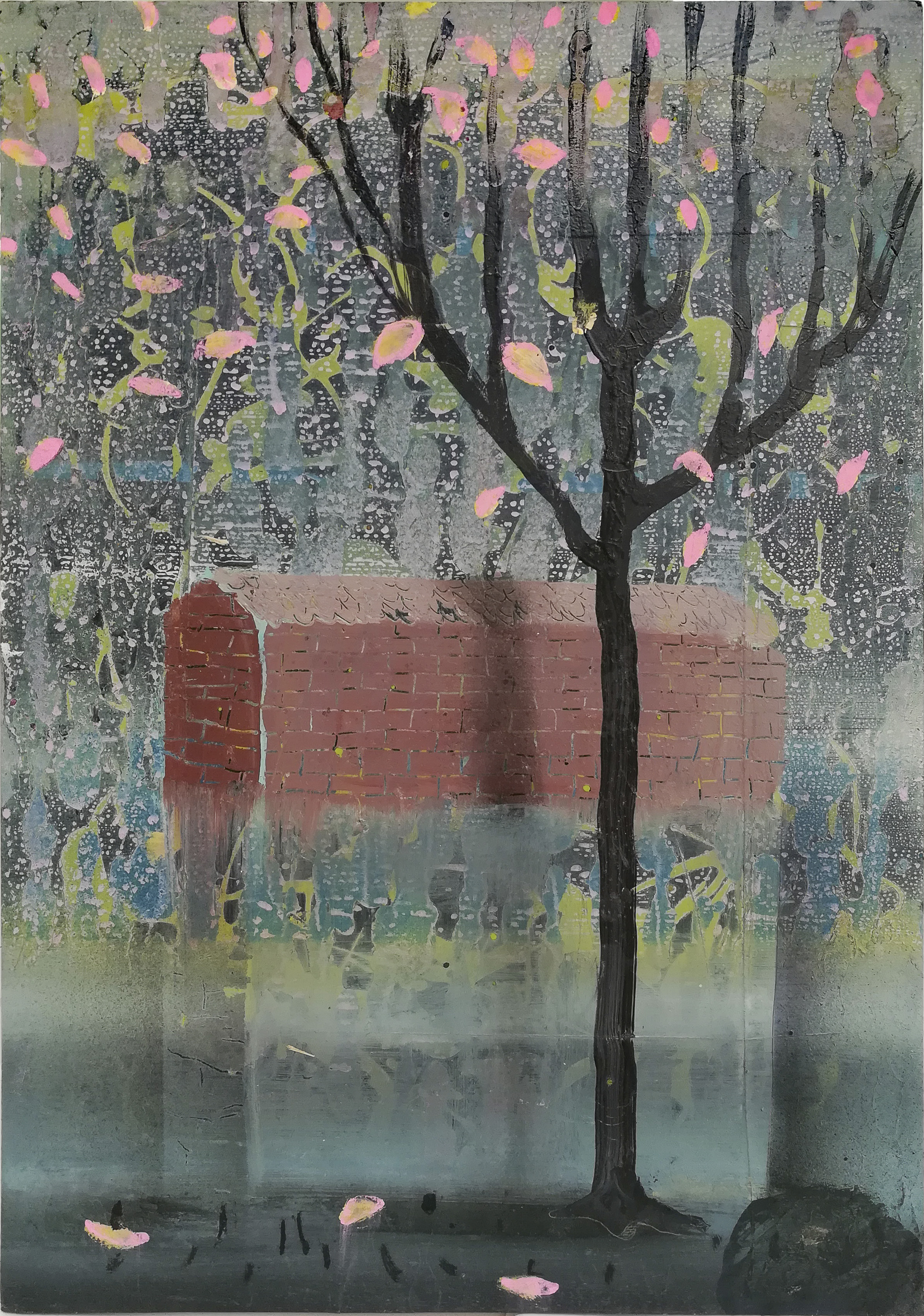

Nevertheless, the various components of his protean oeuvre are all charged with the same energy, with the same striking readiness to expand with force into three-dimensional space. When he paints, Becker Schmitz creates hallucinatory pictures full of spectral beauty, pictures with venomously garish colors in front of bleak and gloomy backgrounds, pictures with weighty materiality and an almost sculptural texture, pictures whose archetypical motifs (house, tree, horse) oscillate in a precarious balance between a pure experience of painting and narratives full of atmosphere. It is at all times uncertain whether the motifs emerge out of the painting surface or, on the contrary, whether they are themselves bearers of surface effects.

When he works with sculptural means, Becker Schmitz treats the respective space in a way that is highly particular. With the simplest of materials – found wooden batons, adhesive tape – he builds dynamic structures, which he wedges between the walls and ceilings, or he fills the exhibition space with inflatable, cumbersome modules, which force the viewer to rethink classical spatial perception. His minimal or obsessive interventions make use of an invasive strategy, which underscores the characteristics of the space and – because they are so obtrusive – simultaneously causes these to disappear altogether.

INTERVIEW

Interview with Julia Ritterskamp

In your paintings, you often – or almost exclusively – work with the theme of nature. How do you find your motifs and what does nature mean to you?

Nature is simply nature. It doesn’t want or need anything from us humans. When I concentrate on this, my painting manifests itself. The idea of art vs. nature has nothing to do with this. What I’m doing has nothing to do with zeitgeist. Doing portraits of well-known personalities would, for example, be zeitgeist. But this doesn’t interest me. That’s just marketing of complacency without risk – as though one were producing goods for an outlet store. Motifs keep coming back again, but the real question is how to paint something subject-like without it actually becoming the subject. Even when I choose a motif that’s been painted a thousand times already, in the end the painting is not about depicting that subject. It’s not about the ship or the cabin, but rather about the material of painting.

The material is just as or even more important than the subject?

It’s always more important. Definitely.

This also means that you want to create something new with your art?

Maybe. But more than anything else, I’m looking for a challenge. I could, of course, just as easily draw and paint everything; but that would be too easy and, in the end, boring.

Does this also have to do with the fact that the way you work and the situation in your studio are highly unusual? Do you want to say something about this?

I darken the studio and create a lighting situation that is unusual for painters. This leads to a whole new relationship to the picture and the material. It’s not about reproducing the subject photo-realistically; for this, I would have to produce a much brighter lighting situation.

What made you decide to darken your studio?

By chance, I took over the studio of a photographer. I wanted to get rid of all the black curtains, but never got around to it because I was so keen on just working. To actually see the pictures, I had to carry them out into the well-lit corridor. I noticed that painting in a dark studio had a different effect on the works – a good effect. And then I wanted to see how far I could take this. I now actually like working this way, but then again I had four years to perfect it, making the studio increasingly darker.

Looking around the studio in the dark, I see only a few lamps placed here and there. It makes me think: Depending on how you look at something (in which light you look at it), you perceive it in a completely different way. It’s all in the eyes of the beholder – also in a metaphorical sense.

Exactly.

In some cases you work alone, and other times you work on projects together with other artists. Sometimes you even paint a picture together with another artist friend, which is otherwise highly unusual. What does working alone or in a team mean to you with regard to artistic production? How do you experience teamwork as opposed to the cliche of the artist working all alone in his studio?

These are all artists who ask the same questions as I do; artists who focus on material. So it’s actually a kind of enrichment; there’s a good level of communication. They know how I work, and also question this. The learning curve is thus increased many times. New questions are posed during the production process and not only afterwards. We are also interested in each other’s artistic development. But I’m very selective: I have here my own highly hermetic space. And, generally speaking, even with regard to normal studio visits, only selected artists and collectors are invited to come in.

What happens to the concept of the “creator” when two artists come together to make one work of art? Is it easy for you to share your creator status with someone else?

Creator status! (laughs) It’s an honour for me! It’s exciting when someone approaches one of my paintings with a completely new perspective, as is the case with the painter Lea Carla Distelhorst. Or in terms of the

BRENNSTOFFzELLE, Il-Jin Atem Choi, who is also a materials researcher – great! Or the photographer Pascal Bruns, with whom I do the HOLD THE LINE series. I can learn a great deal from artists who work in completely different media.

Speaking of “creation”: You’re currently working on a series of paintings about the four elements. It makes me think of metaphysics or esoteric interests. At the same time, however, you call yourself a proponent of “brutal pragmatism”. How does all this fit together?

I’m not at all interested in esoteric concepts and metaphysics. Instead, I look for themes to help me manifest my painting. This can’t be connected in any way to esoteric interests; that would be much too easy.

I’d like to dig a bit deeper here: The works are much more than just material and subject, aren’t they?

I’m not interested in these topics and don’t think about them while I’m painting. A lot takes place outside the realm of language. When a weightlifter lifts something during a competition which is humanly impossible to lift, this is also beyond the realm of language. Just for that moment. But that doesn’t make him a metaphysician. Maybe something metaphysical happens by chance, but I don’t trust this. I’m highly impressed by Caspar-David Friedrich, for example, but only because of his varnishing technique and composition. That’s what it’s all about – not some romantic theory.

What does the connection between art and everyday life mean to you, or rather how do these influence each other?

When I’m in my studio, I work; and when I need a break, I lay down on the couch. There’s no need to talk about Adorno, Heidegger and Arendt here. I don’t have time to rack my brain about the connection between my art and my private life. I want to paint as uncompromisingly as possible. The theory behind this is someone else’s job.

The question was actually meant more in terms of the creative process. Many artists can’t turn it off and are thus stuck in the observation mode – their entire everyday life is “scanned” for artistic potential.

Maybe it’s a kind of art to market “not being able to turn it off” as art.

Do you sometimes think about the potential viewer while working, i.e. how someone could react to the work?

I think more about the exhibition situation, the spaces and what I would like to do with them. In the Kunstraum Bethanien in Berlin, there were something like 2,000 visitors at the opening of “Rekollekt”, and all of them had a look at the BRENNSTOFFzELLE. It’s impossible for me to even imagine what all these viewers could have thought about it.

What do you think about the thesis: When life changes, art changes?

I don’t see myself in my role as an artist as having some kind of special position. It doesn’t matter what job I have – change is inherent in each and every one of us.

During the conversation, the composition of a large format painting takes form. In the lower section, a very small image of the peak of the Matterhorn is depicted – and a lot of empty space above. Because up there, where the air is thin, is where things really happen.

„Pretty cheeky, painting the Matterhorn so small,” Becker Schmitz says and laughs.

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/BeckerSchmitz/

Website: http://beckerschmitz.com

Gallery Website: WWW.VILLA-KOEPPE.DE