Interview with Maria Petrovskaya

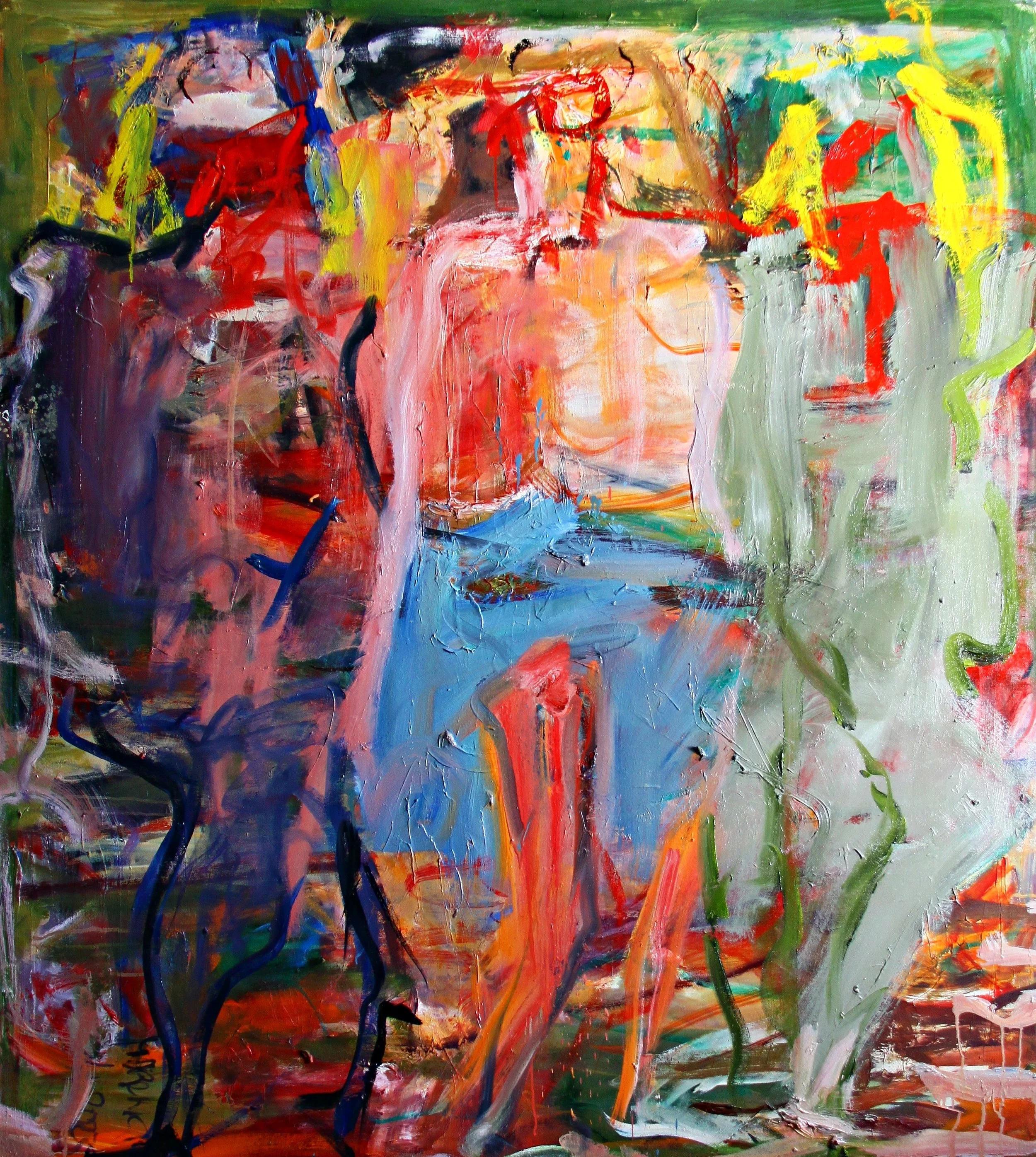

Maria Petrovskaya is a NYC-based artist and curator. She is a graduate of the School of Visual Arts (NYC). Her works in painting and sculpture explore the human body, movement, color, the subconscious, and the surreal.

Her art and curatorial projects featuring emerging contemporary artists were listed as must-see by the Art Newspaper, LA Weekly, Hyperallergic, L’Officiel, and Whitewall Magazine, among others.

How did your time at the School of Visual Arts shape your artistic vision and style, and what were some of the most valuable lessons you learned there?

I think at the very beginning of my time at SVA, I was very wary and apprehensive of art education in general, based on my past negative experience in Moscow. In Russia, even at the time, at the height of openness and democracy, art education was very reactionary and based on the 19th-century European studio atelier system. Only one art style was allowed - generally described as Russian Realism, and any deviation from that wasn't acceptable. Abstraction was nonexistent within school walls, and everything was "my way or highway” regarding faculty-student relationships. It was also very technically rigorous and divided into firm categories that didn’t intersect. Sculpture programs where students mostly copied ancient Greek sculptures were separate from painting, which focused on classical figures, models, etc.

I found the whole system oppressive and the opposite of what was needed to nurture a talent. It was also roughly 120 years behind the rest of the world.

The School of Visual Arts was the complete opposite. It was very open-minded and open-ended and offered a variety of art classes to try different things. People were doing installations, sculpture, painting, and whatever they were interested in. That being said, there was little practical guidance overall unless one was very specific in pursuing their own interests.

I enjoyed having access to the studios and a variety of classes. The general atmosphere and a large student body were conducive to artistic development, experimentation, and growth.

Working as an artist assistant at Jeff Koons LLC, how did this experience influence your approach to art, and what were some key takeaways from this period?

It was a very intense experience. When I was hired, the studio was preparing for a major painting show, working literally 24/7, and we regularly worked overtime, not to mention the level of perfectionism that was standard at the studio. I worked in the color department, where we prepared custom-made oil colors for all paintings in the production. It was sort of a color lab, where we mixed very small amounts (pinky finger size tubes) of hundreds and hundreds of colors to match the printed color swatches provided. Each large painting had 1500-1600 different colors that had to be mixed, meaning hundreds of shades of blue, orange, green, brown, greys, reds, etc. Each mixed color had to be approved by the manager, who checked it next to the printed swatch. It was a complex process, often requiring multiple attempts and sometimes hours of mixing to get the color exactly right. Luckily, I was naturally very good with color and had a very good work ethic, so I produced and got approved vast amounts of colors from the beginning.

Several years of this practice further trained my eye to see the most subtle color variations and to mix them very fast.

Aside from that immediate experience, I got to see and meet people from various other departments of the studio and learn how things are fabricated and the complex processes involved in scaling projects, from tiny figurines and jpegs to monumental sculptures and paintings.

It was also an introspective period, as due to the demands of my studio job, I had little time and energy to physically produce my own artwork. Yet, I had time to think about my art practice, where it stood, and the art at large.

I reassessed the importance of my sculpture practice (I actually started in sculpture back in Moscow, where I learned from mainly copying Greek plaster casts, and then later on, I got into oil painting).

Ironically, not working on something actively, in terms of my art production, just stepping aside, is often very helpful for finding creative solutions. The mind is always working in the background, and being removed from the active tackle helps to see the broader picture while standing at the distance. Physical production can sometimes become a bit of a hamster wheel that hinders strategic thinking.

One of the takeaways was also the side observation that being an artist is a particular way to go through life. For art to flourish, it must be the primary laser focus of one’s life. It requires a certain lifestyle and worldview that is probably the opposite of conventional life in its ordinary sense. Picasso is an example of an artist who understood the demands of art life quite well despite his personal shortcomings.

Your recent exhibitions at SPRING/BREAK, NADA House, and Future Fair have been quite diverse. Could you share how these exhibitions have contributed to your artistic journey and the themes you explore?

I think of it as an organic development: growing like a tree, first one branch, then the next one.

I am focused on the same things that interested me since childhood: the human body, movement, emotion, and color. Every work is a stepping stone to the next one. I like experimentation, but at the same time, I explore the same subjects throughout my life, or at least it feels like that to me.

I also enjoy working with other artists through my curatorial practice. It fosters a sense of community and brings me a sense of satisfaction when I see the exposure it gives to people who work very hard and definitely deserve it. Being an artist is a very challenging life, and a lot of art and artists are hidden, working away in their creative corners, often in difficult conditions. Even a bit of critical exposure can turbocharge an artist to make more work and not lose heart.

How have your paintings and sculptures evolved over the years, and how do you balance the elements of abstraction and figuration in your work?

It might sound wild, but I wasn’t exposed to any abstraction while growing up in Moscow, despite the fact it’s the largest city with a lot of cultural activity. There was basically an iron curtain that went down on art in 1914 in Russia, with the start of WWI. The only Western paintings I could see in the public collections in the museums were works created pre-1914, coming from the confiscated collections of wealthy Russian industrialists who collected early works by Picasso and Matisse. The following years of turmoil after the 1917 revolution led to expropriations, the emigration of major Russian artists like Kandinsky and Chagall, and a general purge of all modern Western art, with Soviet Realism reigning supreme. I think I only saw one Kandinsky painting on view in a public collection in Moscow.

Before moving away from Moscow, I never saw any Jackson Pollock, De Kooning, or any post-WWII abstract artists in the flesh. It was also impossible to find any art books on contemporary art in any bookstores, even in the early 2000ies. There would be dozens of gorgeous monumental books on Renaissance art, all printed in Italy, but absolutely nothing on contemporary art. There was a general public preconception that contemporary art was a kind of trash and often a fraud.

For obvious reasons, when I was starting out, all my work was very figurative, with traditional figure/ground relationships. As I moved to New York, I slowly started incorporating abstraction more and more.

Learning and using the language of abstraction is a complicated task if one doesn’t know it, and just as learning any language and speaking it fluently - it doesn’t come overnight.

The effects of abstraction on contemporary art cannot be overstated - it permeates everything, even if it’s not apparent at first sight.

I also think that abstraction is a somewhat philosophical approach to life, and the best abstract paintings were often made by more mature and older artists, with Mark Rothko being a good example. When people are younger, they usually perceive and describe things more literally.

I do love the human body, so there is always some element of figuration in my work. While the levels of abstraction and figuration in my work differ, these two elements are usually present in various proportions.

Also, combining the figure with varying levels of abstraction is very different in painting and sculpture, mostly because 2D and 3D worlds and languages are vastly different.

Can you elaborate on your unique approach to creating art in social settings, and how this influences the spontaneity and emotional depth of your sculptures and paintings?

I make my sculptures in clay (or, to be precise, the original small prototypes for my sculptures), and I carry small bags of clay with me when I go out. I do my best work in social settings where I talk to others. Ideally, it’s a pleasant environment, like friends’ parties, cafes, etc. It allows me to ease control of my mind and create more spontaneously and intuitively. My sculptures are essentially automatic DADA sculptures, surreal and emotional. It's sort of like snapshots of my psyche at the moment. They are also small, maybe 2- 3 inches max.

I 3D scan and enlarge the best ones, but it’s a long and complicated technological process.

Many of my paintings are also based on automation, starting from small automatic drawings that I make. Similar to sculpture, I choose the best drawings and use them for larger works.

As an artist who extensively uses technology like 3D printing and digital rendering, how do you see technology shaping the future of art, and what challenges have you faced in integrating it into your work?

As an artist, I realized early on that there was a huge barrier to entry for sculpture. This means that any fabrication usually costs thousands of dollars upfront. In painting practice, for instance, the upfront costs are manageable for most people, as it’s just canvas and some paint, and there is a great degree of price flexibility based on what paints you buy, etc.

It’s absolutely not the case in sculpture.

When I was starting, for all the small sculptures that I wanted to enlarge, the process of scaling them up was complex and prohibitively expensive.

I am very grateful for new 3D fabrication technologies and the opportunity it provides to artists. That said, all digital fabrication is still very expensive every step of the way. The only way I could do it was to learn everything myself and get all the equipment I could afford. There are multiple steps - from high-quality scanning (that I actually outsource) to digital rendering and small 3-D modifications, to 3-D printing, to complex postproduction and painting. I do it all myself, and it’s a labor-intensive process. There are usually many things that can and often do go wrong. Physical production/manufacturing is complicated, unlike digital renderings, which are easy to make.

I think the breakthrough in technology is amazing, though interestingly, I learned that many of these 3D technologies were available a while ago. The only reason there is now this whole new wave of more accessible technology is that the 3D patents held by a few major monopolist companies have expired. It allowed smaller start-up companies to enter the market and offer cheaper mass-produced 3D equipment to consumers. The young Chinese companies very ambitiously pushed the 3D design market by greatly expanding the printing scale and knocking down prices to mass affordability. It greatly expanded the field. So, it shows that any kind of technological monopoly can hinder the future wide implementation of technology for artists.

I use technology as a tool for fabrication, but the core component of my art is a very human emotion and experiences that come from the heart. I do believe that good art ultimately describes what it feels like to be a human and all human experiences.

Also, I think that chance and the physical properties of the materials are very important parts of the creative art process.

Reflecting on your unique journey, including your transition from Moscow State University to becoming a professional artist and your move to New York, how do these profound life changes manifest in your art, particularly in the way you represent themes of identity and transformation"?

I grew up in a very traditional environment, and almost everyone in my family had a science background. Yet, I remember passionately wanting to be an artist as a child, and honestly, I don’t know where or how I got that idea. I just really loved drawing and making things. Art wasn’t a career option from my family’s standpoint. I was also very academically inclined and genuinely enjoyed math. So, I tried not being an artist and studying at Moscow State University as my family expected. I was very unhappy there and eventually left to pursue art.

Yet, I was acutely aware that I was leaving behind a stable career path and that the future would not be rosy. When I set my eyes on getting an art education or at least some technical art skills, I encountered repressive 19th-century style Moscow art schools and a general absence of contemporary art. However, at that time, I didn’t even fully realize how much I was missing. I still spent several years there struggling and learning art skills.

I read that New York City had the highest concentration of contemporary art in the world, so I moved here eventually.

I think art reflects everything that happens in life and the world at large, as it is a reflective pursuit. After all, we visualize past civilizations and their lifestyle through the art they left behind.

I am sure my art reflects my life journey and environment and is probably somewhat autobiographical.

From my own lived experiences, I came to the conclusion that freedom is an absolutely essential ingredient for art to flourish. It’s a quintessential component, though I think it’s often overlooked or taken for granted.

I think that the amazing dynamic art of Ancient Greece that rapidly developed within the scope of several centuries is directly related to the fact that Greece had democracy at that time. It’s opposite to Egypt, with its pharaonic rule and a static, formulaic art that preserved the same exact canons for thousands of years.

NYC is a very diverse, tolerant, and open-minded place, and it was one of the first things that struck me when I moved. That’s one of the reasons that art is flourishing here. Freedom is reflected in art, and I hope it is reflected in my art, too.

Coming from a very rigid environment in my home country, I always felt I was on a journey towards greater freedom. I think an artist's goal is to realize their own specific talents (in all meanings of these words) and have an authentic art and life.